When I was a teenager, I took an art class at a place called the Guild of Artists. It was in the center of the town where I grew up, yet also set back in the woods. I don’t remember the class or what I made, but I remember that behind the Guild of Artists—which was a small stone house—there was a pond of exceptionally still water. Someone told me a body had been dumped in the pond, and even though they might have been making it up, I associated the pond with that body and the Guild of Artists with the energy rising off it. The stillness of the water suggested to me a layer of protection over what I imagined was the body’s privacy and transformation. Like I said, I don’t remember what class I took or what I made, and it did not, in the end, seem to matter as much as the questions the pond—and the idea of the body—posed to art and art-making.

I had a recurring nightmare when I was young that felt like being trapped in a drawing. I tried to describe it here. It felt, actually, like being trapped in the process of a drawing being made, then that drawing growing out of control. It was, in that way—and at that age—the world. And it felt like the world was being transformed into a drawing that became, in my inability to handle it, sentient. I never cried in the dream—I was stunned into silence—but I always woke up inconsolable, screamed out for my parents to save me.

Some trees, light green or fall colors, remind me of my mother when I was young. They remind me of the trees where I grew up, and imagining my mother staring out the window of our house, wishing she was somewhere else. I was an artist before I was a poet, although now I’m not sure that makes sense. In addition to the Guild of Artists, I took art classes at an art center a few towns away. My mother took classes there too. She is an artist. She had an exhibition at the Poetry Center, 2012-2013, called From What I Gather…

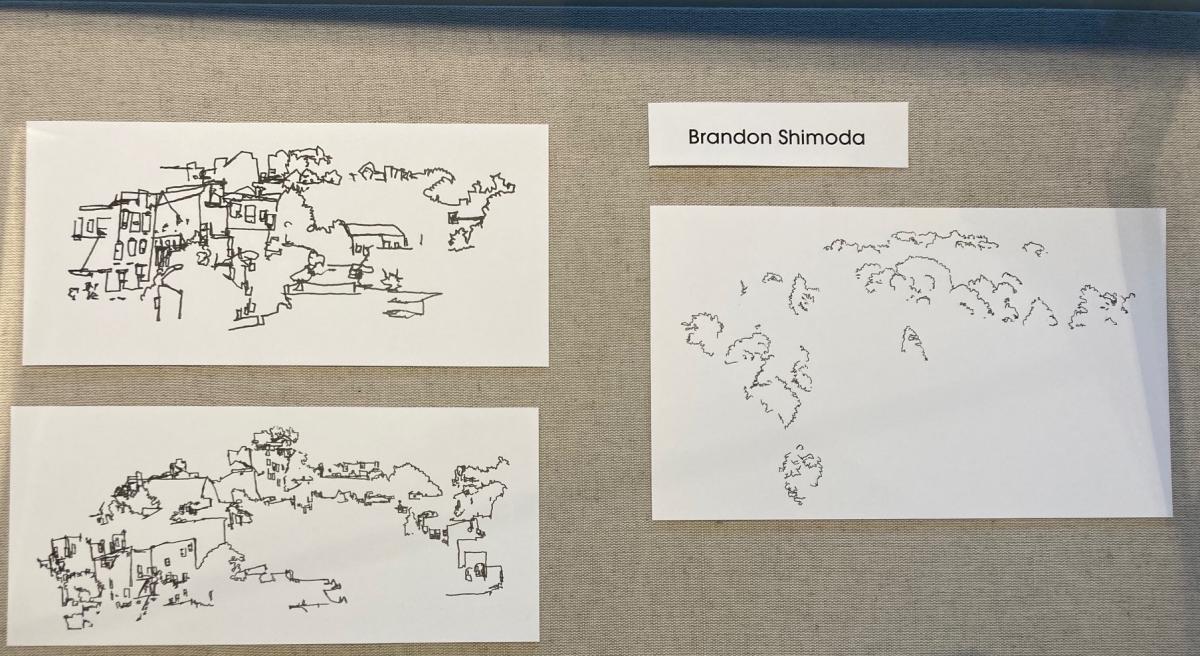

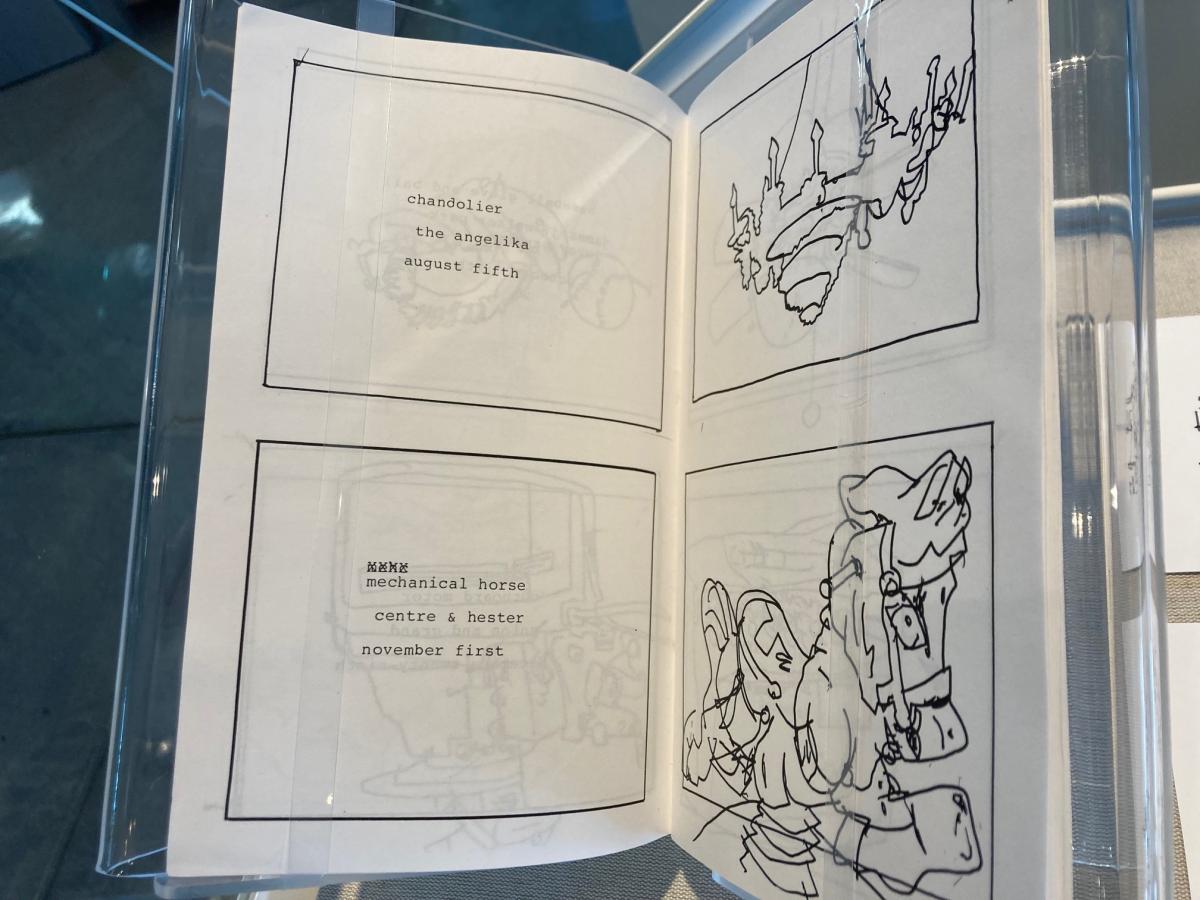

When I was in undergraduate school, I went to an art exhibition in Chelsea, NYC—Poetry Plastique, Marianne Boesky Gallery, 2001—and saw a wall hanging, text and photographs, by the poet Leslie Scalapino (“What’s place—war in night”), and I thought, in the moment of seeing it: I want to do that, which I translated as: I want to be a poet. I was making art then—sculptures, installations, photographs, street drawings, i.e. of things I found on the street: coin-operated rides, weeds, dead birds. Maybe they were poems. I think I wanted them to be experienced as haiku.

Eight years ago or so I spent a week in a hotel in Brooklyn. My partner Dot Devota and our friend Caitie Moore and I were invited to collaborate on a book. We were given a room on the third or fourth or fifth floor and free food. Dot and Caitie wrote letters to each other while I stood at the window and drew what I saw. There was a destruction site, a pit of dirt with workers, surrounded by buildings and trees, so that’s what the drawings were: workers, buildings, trees. Dot and Caitie’s letters to each other and my drawings were published as Dept. of Posthumous Letters (Argos Books, 2018). Looking at the drawings now, I’m most attracted to the workers. The buildings have aged, the trees are overgrown, but the workers are fresh, because they look like they are still waiting. For what? For the work to end? For the work to begin? To be returned to their families, tranquility, music? It is clear they love each other. For one among them to move closer? To be honest?

I used to think that when I had a falling out with poetry, I turned to prose, that when I had a falling out with prose, I turned to poetry, and that when I had a falling out with writing, I turned to drawing, but it’s not true, I need to think about that. No medium is a consolation. Poetry, prose, drawings—they do not compensate for each other or for my failure to bring myself to them. Am I the medium? The falling out is with myself.

There have been periods when I stopped writing and returned to drawing, which felt like returning to childhood, when there were no distinctions. During one of these periods I drew dozens of abstract shapes that looked like muscles torn from bodies and suspended in space. I made the drawings on a computer. I started with a line, then stretched it, bent it, repeated it, made it echo, until something uncanny emerged. It sounds like writing a poem. Is the other way true? I have drawn my way into a poem, and I have written my way into a drawing.

I asked my mother if she did, in fact, stare out the window of our house. I don’t remember so much staring out the window, she said, as I remember lying on that plaid convertible couch in my studio… I’d go into that room, my space, and become inert. I’d lie there on the couch and mope about how I wasn’t doing anything with my life. I wanted so badly to be doing something. I wanted to be of importance, beyond being a mother. I’d dream about what I could be doing. Maybe while my mother was on the couch, I was looking out the window. Maybe drawing is the consciousness of—and the consciousness surrounding—the dream. If not the dream, then the dreaming.

When my mother was pregnant with me, she took a class on color theory. For her final assignment, she made a painting. (I wrote about it, including the two sentences above, here.) It’s my favorite painting. For many reasons, one of which is that it is proof. Not that I was born—that I am alive—but that I was once about to be, which is more exciting.

Brandon Shimoda is a yonsei poet/writer. His books include The Grave on the Wall (City Lights) and The Desert (The Song Cave), and two forthcoming books: Hydra Medusa (poetry and prose, Nightboat Books) and a book on the afterlife of Japanese American incarceration (City Lights). He lived, for many years, in Tucson.