The best thing about Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s poem “Baked Goods” is that it has rats in it.

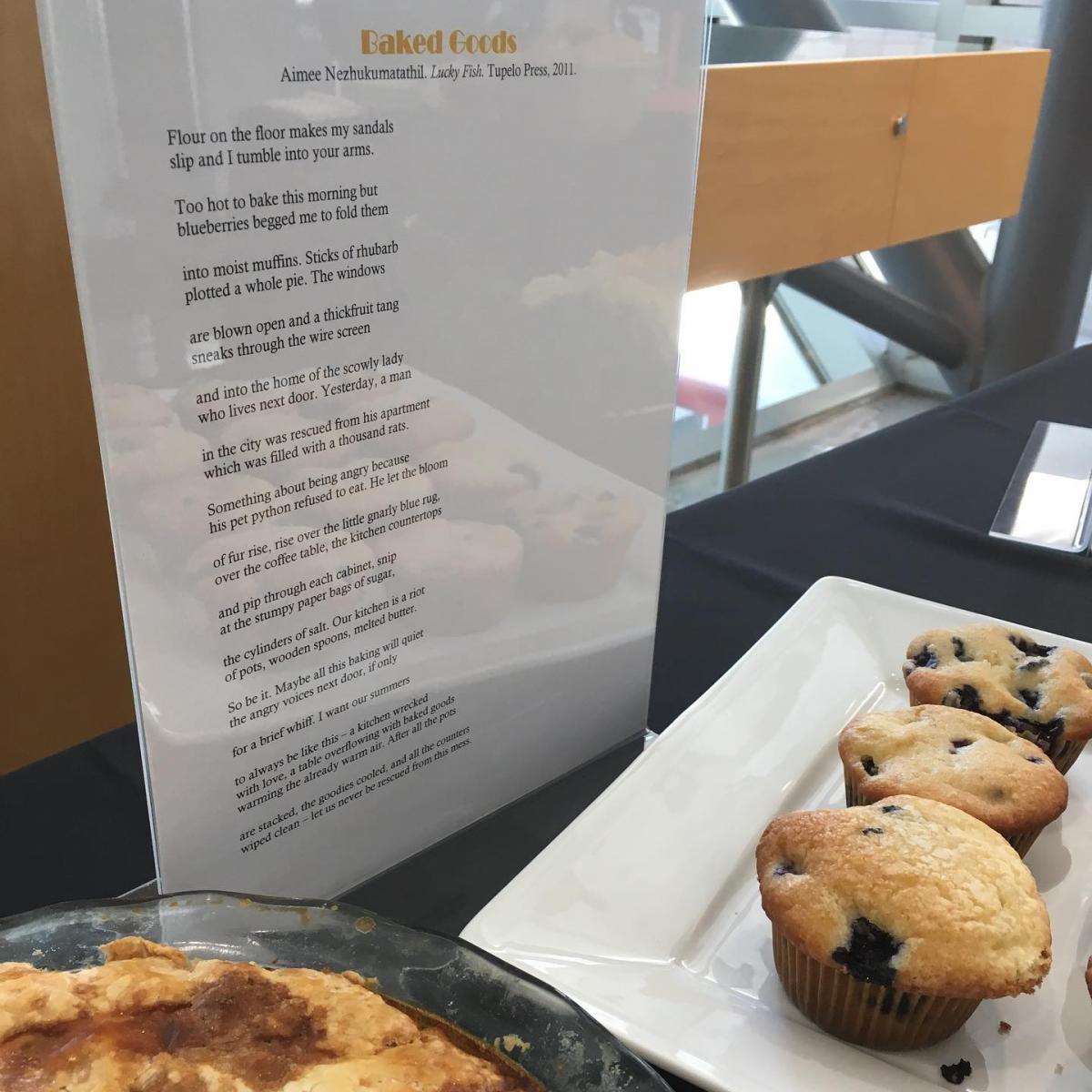

To be fair, when I first came across it—I was looking for a poem to bake for the Come to the Table opening reception—it wasn’t the rats that drew me in. Rather, it was Nezhukumatathil’s description of a lazy day spent with a sweetheart in the kitchen: blueberries and rhubarb becoming muffins and pie, flour everywhere, the oven making a hot summer day even hotter. The lush chaos of “a riot of pots, wooden spoons, and melted butter” reminded me of my own kitchen on Sundays, the one day of the week my partner, Tyler, and I both have off. We recently moved to a small town an hour and a half east of Tucson, and limited entertainment options mean more time spent around the house—Tyler tending the pots of peppers and herbs on the patio as I practice my pizza dough and turn piles of peaches from the you-pick orchard down the road into salsa and ice cream.

But, as I read the poem over and over, it was the rats that came to the fore. Of them, Nezhukumatathil writes:

Yesterday, a man

in the city was rescued from his apartment

which was filled with a thousand rats.

Something about being angry because

his pet python refused to eat. He let the bloom

of fur rise, rise over the little gnarly blue rug,

over the coffee table, the kitchen countertops

and pip through each cabinet, snip

at the stumpy bags of sugar,

the cylinders of salt.

Rats are—probably somewhat unfairly—associated with pestilence (see: the Bubonic plague) and a disturbing resilience (at the end of The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, science journalist Elizabeth Kolbert suggests that, when humanity is gone, giant rats will take over as the dominant species on earth). They lurk at the edge of human existence, scurrying through Subway tunnels, ready to eat all the food in our cupboards if given the chance.

The story about the rats sits in the center of “Baked Goods,” tucked between a love letter written in butter and fruit. A kitchen wrecked with rodents is only five lines away from “a kitchen wrecked with love,” destruction and bliss so close they’re basically intertwined.

*

In “Showing Up For Love,” part of Eshani Surya’s essay series The Marrow Scripts, she writes about making birthday cupcakes for her boyfriend while experiencing an acute medical event related to ulcerative colitis:

I have a fantasy of how this will all turn out. The cupcakes will rise evenly, and cool without much issue. Z will be somewhere upstairs, or maybe out by the lake, and when he comes inside, he’ll be surprised by how clean the kitchen is, how bakery-ready the dessert looks, how beautiful I am, a proud baker with a large smile tugging at her mouth. Then, we will eat.

But I can’t stand at the kitchen island for more than a moment at a time. As soon as I mix an ingredient, I feel an overwhelming need to run to the bathroom. My hands start to go raw from the amount that I wash them. I think about the gas I’m wasting by keeping the oven on, but I can’t power through the recipe in one long stretch. I am staccato. I am far from my fantasy self.

A “bloom of fur”—whether illness, white supremacist capitalist patriarchy, or some other circumstance—always threatens to erode the best laid plans, the perfect recipe, the long-practiced motions of folding eggs into batter and whipping up frosting. In “Showing Up For Love” it’s illness, in “Baked Goods” it’s rats, and when I turn to my own cooking life and tug at the edges, all sorts of disquiet spills out.

*

Like Surya, I use cooking and baking to shore up my life, especially when I need solid ground to stand on.

I repair to the kitchen when anxiety disorder and depression get the best of me, and cherish how working with my hands pushes back against the online scrolling that puts my brain in the darkest places, or the loneliness I’ve carried since childhood. I cook as a way to love the living and honor the dead—this past spring a friend and I, both of us of Italian descent, spent evenings preparing biscotti, zeppoles, and cannoli, as though we could sweeten our way back to a heritage we were, for different reasons, separated from. And I make food and drink, like Nezhukumatathil does in “Baked Goods,” as a collaborative expression of romantic love: Recently, Tyler invited me to the winery where he works to crush leftover grapes that were otherwise bound for the compost. I headed over and, after sanitizing my feet, jumped in to a plastic bucket full of sauvignon blanc clusters and squished the sugary juice out with my toes and heels as we laughed and joked. “I thought this would be a fun date,” he said as we carried the grape stems and skins out to the compost, bats swooping in the night sky above us, and sealed up the bucket that held our someday-wine.

But acts of culinary making never turn out as simply or perfectly as I imagine—to borrow a metaphor from “Baked Goods,” there are always rats. A recipe gone wrong can bring my anxiety-mind back to the brink of a panic attack, food resting on the counter while I stare at the ceiling trying to breathe. No matter how delicious the cannoli filling tasted or how lovely the sugar-dusted zeppoles looked, I couldn’t separate the desserts my friend and I made from the complexities of being adopted and the birth father—from whom I get my Mezzogiorno ancestry—who died from liver failure at age fifty, his disease driven by the same set of mental illnesses tucked into my genes. And a few days after crushing the grapes, Tyler texted: Will probably dump our juice. Honestly don’t have the mind space for it. It was harvest at the winery and he was working twelve hour days—it made sense that stress seeped in and, anyway, the whole activity was just a fun way to spend time together. It wasn’t a big deal. Still, my heart sunk as I thought about him tipping the bucket over and letting the juice we pressed pour down the winery’s industrial drain.

*

Even if they aren’t poured down the drain by a very reasonably stressed partner, food and drink—by their very nature—decay. The most carefully crafted meal turns into compost or shit or food for chickens, leaving nothing but memories and a sink full of dirty dishes in its wake. You can take photographs or write down a recipe, but the food itself doesn’t last: you can’t keep it.

Capitalism is obsessed with legacy and output, with building things that will outlive you. The drive to produce feels toxic and like it creeps into everything, from wage labor to writing and art-making. There are days when this turns my stomach for hours. And—while I know it won’t fix anything, that’s it’s not actually in solidarity with anyone, that there is so much work to be done—pulling out pots and pans and beginning to chop up vegetables is the best temporary respite I know. On those days, the practice of putting so much work into something that’ll ultimately be gnawed by stomach acid feels like a gift.

Still, it’s tempting to steel myself against decay, to love Surya’s “fantasy of how this will all turn out” more than I love the rats and other pests that prey at the edges of Nezhukumatathil’s “table overflowing with baked goods / warming the already warm air.”

*

A few days ago, a friend posted a video of their toddler, Ruby, eating an olive. In it, Ruby takes a bite and then reaches out their hand, offering the snack to a friend. I’ve seen them do this before—they’ve tried to feed crackers to their dog and handed me half-chewed bits of fruit—so I look for who they’re giving the briny treat to. I can’t see anyone until the camera focuses on the back of a chair, where a tiny pest quivers an inch away from Ruby’s outstretched hand.

Ruby is trying to share their olive with a fly.

Wren Awry is a K-12 Education Coordinator at the University of Arizona Poetry Center; an essayist; the editor of Nourishing Resistance, an interview series about food and social change; and the instructor of Food is Connected Everything: Writing the Culinary Essay, which starts on October 15 at the UA Poetry Center.