I recall a conversation over wine on the 45th floor of my apartment nestled along DuSable Lake Shore Drive, where Diego Báez gave a reading of his poetry for the Mercy Street Reading series. It was a full house. The window dimmed against the skyline. Throughout the night, he shared insights into his creative process and his vision for the future of poetry with so many in attendance. Diego embodies the spirit of a guardian of the literary arts. Voices like Diego’s are more necessary than ever; his contributions as a writer and critic guide us with curiosity and an unwavering commitment to poetry’s capability.

encounter each other through the elusive yet potent figure of the jaguar.

Diego Báez is an acclaimed critic, poet, and educator. His new collection of poetry, Yaguareté White, is an exceptional debut. Published by the University of Arizona in February, Yaguareté White was recognized as a finalist for the Georgia Poetry Prize and a semifinalist for the Berkshire Prize for Poetry. Poet Daniel Borzutzky says of the book, “Báez brings us a vision of Paraguay that has yet to be seen in U.S. poetry.” The collection plots a route illustrating how English, Spanish, and Guaraní all meet.

The son of a Paraguayan father and a mother from Pennsylvania, Báez grew up in Central Illinois and was one of the only brown kids on the block. This blend of languages is a "language of firecracker diacritics," an animated and lively mix that captures a story of grief, exploring both national and cultural sense of self.

Over the past few weeks, I had the unexpected opportunity to exchange ideas with Diego Baéz while he was on the road promoting his new poetry collection, Yaguareté White.

Ruben Quesada: Hi, Diego. When I learned that the UA Poetry Center Blog was accepting pitches, I jumped at the chance. My partner spent his formative years in Tucson, and we have been visiting every summer for the past few years. I went to the Poetry Center for the first time in 2021. It was the summer of 2021 when COVID precautions on airplanes caused civil liberty violation claims, with social media videos going viral. Tyler Meier was very generous and gave us a personal tour, including time in the rare book room. Have you ever been to the University of Arizona Poetry Center in Tucson?

Diego Báez: Sadly, no! I had the pleasure of visiting Tucson, Arizona, for the first time in March (2024) to present at the Tucson Festival of Books, and we made a family trip out of it. Dear friends, I have lived there forever, and my dad and his wife reside in Scottsdale, AZ, for part of the year. It was the first time my dad heard me read from the book, so that was special. We made it out to the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, which is just lovely. Sonoran flora and fauna are spectacular, so alien and strange, at least to a midwesterner raised among cornfields and soybeans. I didn’t get a chance to visit the Poetry Center, but I certainly plan to return. It’s at the top of my list of Tucsonian destinations, together with Biosphere 2 and the Davis-Monthan Air Force boneyard. Road trip?

Ruben: I like the idea of a road trip. I’d consider it. You were at the Tucson Book Festival, where you gave two presentations. One is titled “Dual Identities In America,” experimental poets discuss how their heritage has impacted their poetry and lives. The other, “What's New in Latino Poetry,” is about contemporary themes of Latino identity. What were your biggest takeaways from the festival?

Diego: I feel fortunate to have shared panels with three phenomenal poets. Manuel Paul López—who I know from way back in our CantoMundo days—shared the work of Gina Ann Garcia, a public scholar who focuses on Hispanic-Serving Institutions. Tim Z. Hernandez read a poem about a daughter whose child is older now than in the piece. As a new father, that really, really moved me. Reyes Ramirez, a prolific new writer with a book of poetry and a collection of short stories already out—and a book of essays on the way—handed out neon copies of a rad zine he puts out in Houston that investigates advertising towers in the area. It was an honor to join them in conversation, even if we couldn’t conclusively decide what, indeed, is new in Latino Poetry.

in the United States. The festival takes place annually on the University of Arizona Campus.

Ruben: Our respective families are bilingual, with roots in Latin American countries and other areas. I grew up speaking Spanish; my family originates from Costa Rica. When I had the honor of blurbing your book, I described your poems as a voyage from Paraguay to Pennsylvania, highlighting languages—English, Spanish, and Guaraní. I felt a connection to your poems. The verbal exchanges were dynamic and, at times, familiar in their awkwardness, but your curiosity drove your observations and made the situation accessible, even when I didn’t understand an exchange. Did this collection bring you any discoveries or resolutions about your book's concerns?

Diego: I’m so grateful for your perspective, and I hope the book’s themes of linguistic uncertainty and cultural contradictions resonate with other readers who share experiences of multicultural, multilingual families. If anything, the book—and its reception—have confirmed the trickiness in translating overlapping, occasionally confusing ethnic, racial, and national identities into poetry. Just by way of one example, when discussing the book’s uses of Guaraní and Spanish, one reviewer remarked that “Báez does not speak either language,” which is both accurate and not. Guaraní escapes me, but my touristic Spanish is passable. (I only press into more meaningful conversation when I’m in Paraguay, among family.) So, I can’t claim to “speak” the language, per se. But it’s really these kinds of questions I hope the book can complicate, even as it tries to unpack them.

It’s important to me that my poems must speak to readers

who wrestle with the languages of their ancestors, whether they be

indigenous or dominant. (Or, in the case of Guaraní, both.)

Ruben: That’s so fascinating, because I noticed some interesting inconsistencies in your book. Many poems are in English, some have Spanish sprinkled in, whereas others incorporate all three languages you’ve mentioned: Guaraní, Spanish, and English. When you write, do you set out with the intention of combining these languages? or does it arise organically throughout your writing process?

Diego: For the most part, I throw in Spanish and Guaraní where it feels natural or most fitting for the situation. So while I think it’s more organic than intention, it does seem like the memory poems and more historically critical poems split languages fairly evenly. I’m not sure what that means, other than, I will say, feedback I got on an earlier draft of the manuscript asked for more Guaraní. In response I wrote two poems, both of which entailed a process directly opposed to what I just described. “English Eventually” was a direct response to this editorial challenge or request. The poem opens with the lines:

An editor asks for more

Guaraní in the manuscript.

I transcribe—by hand—

every word of Avañe’ẽ I know

It was only in researching the language more that I learned the word for “Guaraní” in Guaraní. So what started as a kind of smart ass retort transformed into an answer to a question I didn’t know I needed to be asked.

Ruben: Do you like languages? I’m fascinated by languages. As soon as I was able to study languages in school, I took French. I studied it for two years and took a self-directed semester of it. I also studied Latin, Russian, and Italian, but more informally. Do you have any research plans in South America to study Guaraní?

Diego: My dumb ass entertained Latin for a semester in college. Like, why? But, yes. One thing that drew me to using the word “yaguareté” in the title of my book is also how it looks—relatively long and awkward, confounding perhaps for unprepared readers—especially when paired with the racially charged single syllable of white.

Guaraní fascinates me in that way, as well. In one poem, I refer to the “firecracker diacritics” of the language, and it was wild, having grown up hearing it spoken so often. Seeing Guaraní written out, I came to understand that the sounds of the shapes didn’t—still rarely do—conform at first to my expectations for them. It’s part of a learning curve I hope continues to bend toward prehension.

I’ll give you one guess as to how to pronounce “mba'eichapa.”

Ruben: I love the string of vowels, but I’d never get it. I’d like to phone a friend. Andwhat are you currently reading or excited to read?

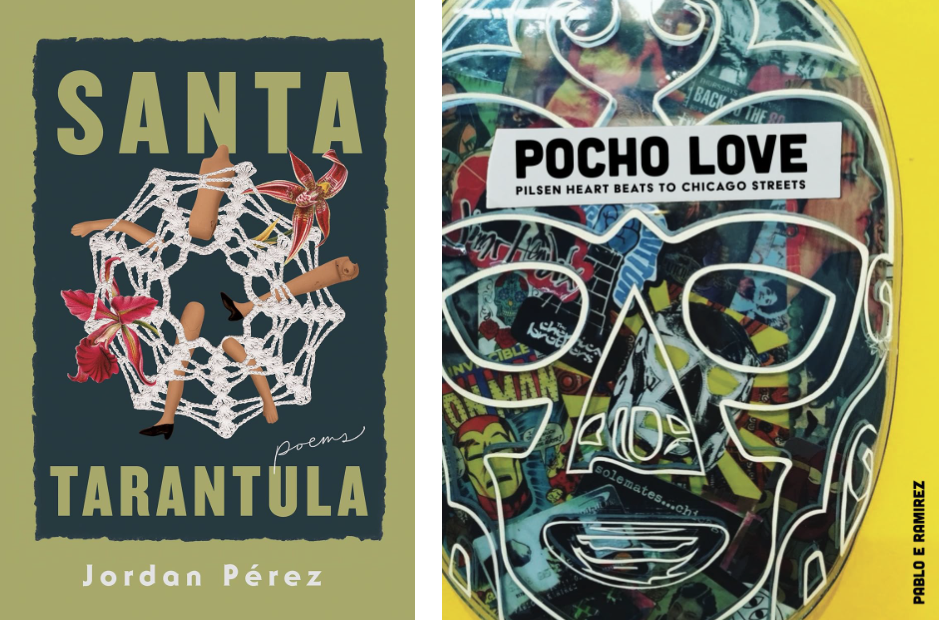

Diego: Santa Tarantula by Jordan Pérez is easily one of the best books of the year. In its architecture and tone, it reminds me of Diamond Sharpe’s Super Sad Black Girl, if not in subject matter or style. Chicago poet Pablo E Ramirez released an impressive, full-color collection last year, Pocho Love: Pilsen Heart Beats to Chicago Streets. I highly recommend it.

I’m looking forward to reading GALAXIAS by Haroldo de Campos and Fabulosa by Karen Rigby later this year for Letras Latinas Blog 2.

and Pocho Love: Pilsen Heart Beats to Chicago Streets by Pablo E Ramirez (right).

Ruben: I’m also excited about Fabulosa. JackLeg Press has been putting out great work. And it’s so important to support indie publishers, especially since Small Press Distribution shuttered earlier this year.

Is there a passage from your book, Yaguareté White, that would resonate with most readers?

Diego: Here’s the opening couplet from “Regalito.”

Some immigrants stuff language into duffel bags like contraband.

Other children never learn to handle the baggage of their claim.

At readings, this poem, in particular, seems to resonate with folks, even those who didn’t grow up with an immigrant parent who tried—perhaps failed—to transmit a language wholesale from their homeland to their children. It’s important to me that my poems must speak to readers who wrestle with the languages of their ancestors, whether they be indigenous or dominant. (Or, in the case of Guaraní, both.)

Ruben: Finally, do you have any upcoming readings or events where fans can meet you and learn more about your work?

Diego: On Friday, May 17, I’m doing an event in Chicago at Pilsen Community Books with Angelique Zobitz. That’ll be dope. Angelique’s book, Seraphim, is incredible. Next day, I’ll be in Knoxville, Tennessee at Union Ave Books for an event with Erin Elizabeth Smith. I can’t wait to reconnect with her, and the bookstore is one of the best.

Ruben: Thank you so much for answering my questions, Diego. I’m thrilled about your collection, Yaguareté White. Also, I wanted to say that your release party in Uptown was terrific. You had the best cookies. And the harpist really brought the whole evening together. It felt like the perfect pairing with your poems, which are so musical in their own way. Is that something you think about consciously?

Diego: Rhythms and syllabics have always been important to my practice of poetry. I’m obsessed with the hidden structures we can layer into our lyrics that give the mind’s ear subtle (or obvious!) hints and rewards. “XXII” by William Carlos Wiliams is one of my favorite examples of underlying syllabic structures that add another level of profundity to what is arguably one of the most striking poems of the 20th century (certainly one of the most enduring). My hope is that readers will indulge themselves and consider some of these same aspects within my own little poemas. Hopefully, it will prove worth the while!

Ruben Quesada is the author of Brutal Companion, winner of the 2023 Barrow Street Editors Prize, out October 15, 2024. He edited the award-winning anthology Latinx Poetics: Essays on the Art of Poetry (2022). A former board member of the National Book Critics Circle, Dr. Quesada teaches writing & literature at Columbia College Chicago, Antioch University’s low-residency MFA in Creative Writing program and the Pan-European MFA Program in Creative Writing.