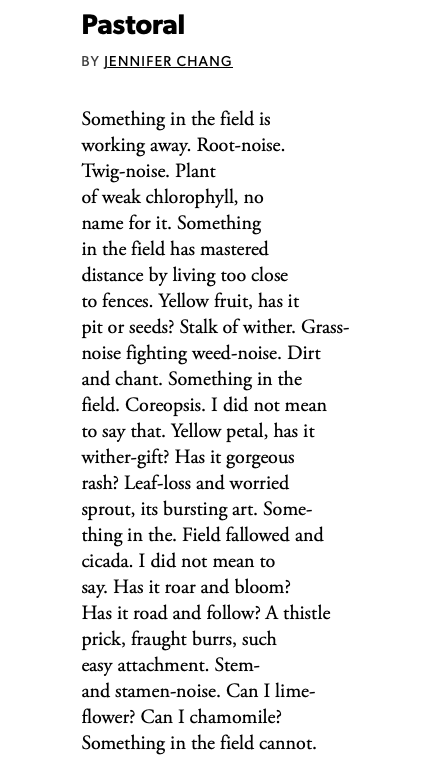

Something in the field is

working away. Root-noise.

Twig-noise. Plant

of weak chlorophyll, no

name for it.

It’s the season of something working away. Roots have been spreading below the thawing earth, buds are about to burst. Here, in south Louisiana, the Japanese magnolias are among the first to flower: pink teacups on bare branches. I read on Instagram that these petals are edible and taste like ginger, so this afternoon, I ate one petal from a neighbor’s tree. It was cool and good. Something in the neighborhood is working away. I listen for the “root-noise” and “twig-noise.” In my city, these sounds compete with the sporadic rhythm of heavy rain on the shotgun house eaves.

Mardi Gras suddenly seems ages away, after feeling “like yesterday” for a few weeks. This is a marker of spring, along with unpredictable warming weather. Last night, I slept with my space heater on, but the previous Wednesday saw a high of 81 degrees. Monday, the streets flooded from a passing storm. Who knows what’s next. It’s been strange, and we are ready for things to be green again. We find comfort in that constancy: “Something in the / field,” Jennifer Chang writes, again and again, with varying degrees of line break and syntactical completion. The uncomfortable line break and sentence fragments are lyric impulses, forcing us to seek meaning in what hasn’t fully flourished.

The splintered form held together by the “noise” of Chang’s “Pastoral” feel oddly un-pastoral. Pastorals celebrate nature without the human, whereas ecological writing remembers that the human is part of it: we are intertwined with other beings of this world that is the homeplace of us all. On the first day of spring, it seems easier to remember these entanglements—the in-betweenness of seasons—as we wipe the pollen from our windshields and chase the mice from our winter closets. The change of a season is not the flipping of a switch: it is a shift, lyric and translative.

The term “lyric” often evades definition. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics’ extensive entry on “lyric” notes that the etymology of “lyric” stems from the word “lyre,” a nod to its musicality, its collective-ness. Ecopoets Marthe Reed and Linda Russo combine “lyric” with “eco” to create the adjective/noun “ecolyric,” which they define as “pertaining to feelings of home, expressed musically.” They remind us that the root of “eco” is oikos, which means homeplace. Lyre-noise. Pollen-noise.

The poem ends on a pair of evocative questions and a mysterious answer:

“Can I lime- / flower? Can I chamomile? / Something in the field cannot.”

Is Chang’s “Pastoral” a pastoral? Is it ecolyric? I’ve been mulling over this poem as the equinox approaches. It is definitely lyric in its musicality and refusal of narrative devices. It is definitely ecological in its attention to the field, as its own ecology. It doesn’t idealize nature or see the human as distinct. But where doe the speaker fit in? Is the field her home-place? “Pastoral” depends on image, musicality, parataxis. It’s a poem of displacement, disturbance. In an interview for the blog “How a Poem Happens,” Jennifer Chang states that she “abide[s] by the conception of lyric as the displacement of narrative.” This concept is reflected in the poem’s unnerving syntax and lines, which break where it feels least comfortable.

Paradoxically, the poem also depends on portmanteaus, creating new words by hyphenating familiar words together. It creates nouns of verbs, verbs from nouns. It questions language as we know it, creating a new one that reflects the anxiety of spring. This blending feels like the “collaged, curated, compostive, translative" element of ecolyric described by Reed and Russo. The poem ends on a pair of evocative questions and a mysterious answer: “Can I lime- / flower? Can I chamomile? / Something in the field cannot.” “Pastoral” is elusive, even as it situates us. I feel at home in this poem, and this poem feels to me like spring, in all its bursting and hope and doubt and dread. Something in spring is an ending, unable to root. In south Louisiana, it is the season that means summer is close and that soon the world will be heavy, wet, and hot. Will this be the year of the next big hurricane, its roar and bloom? Can we flood-float?

this poem feels to me like spring,

in all its bursting and hope and doubt and dread

I think back to the pink magnolia blossoms: these trees flower so early, but once the petals drop, they’re gone until next year. Foliage will fill in the petals’ absence, and the trees will be green until the leaves drop in fall. Blossoms will burst forth again in a year. Spring, Chang’s “Pastoral” reminds us, is fraught: it is an entanglement of beginnings and endings, nourishments and fears. The winds pick up, the sun gets hotter, and the days are suddenly bright past 6 PM. I don’t know what to do with it, but I feel a warm panic: lime-flower and chamomile. Chang’s “Pastoral” helps me feel at home in the unknown of it all.

____

Stacey Balkun is the author of Sweetbitter & co-editor of Fiolet & Wing. Winner of the 2019 New South Writing Contest, her work has appeared in Best New Poets, Mississippi Review, Pleiades, & several other anthologies & journals. Stacey holds an MFA from Fresno State & teaches online at The Poetry Barn and The Loft. She lives and writes in New Orleans.