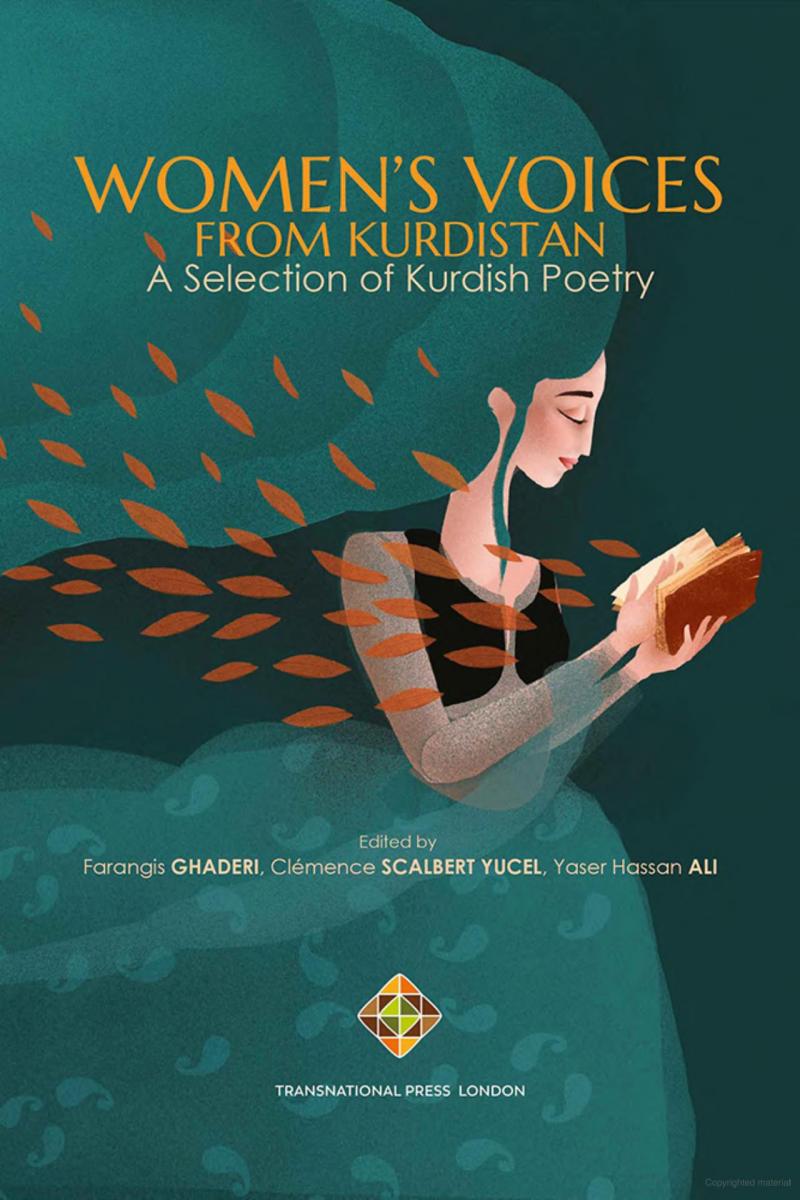

Women’s Voices from Kurdistan: A Selection of Kurdish Poetry was published by Transnational Press London in 2021 and is a trailblazing collection for Kurdish literature, female writers, and Kurds in diaspora. What began as a two-day workshop with PhD students, researchers, and scholars in translation studies and Kurdish studies at the University of Exeter, has turned into this powerful book edited by Dr. Farangis Ghaderi, Dr. Clémence Scalbert Yucel, and Dr. Yaser Hassan Ali. I am eager to speak about the importance of this book and the window it offers its readers.

Within the literary translation landscape, Kurdish poetry and prose in translation (into English) is not as widely available as translations from other SWANA region languages (like Persian/Farsi, Arabic, and Turkish, for example). Fragmentation and fractures of all types—political, geographical, colonial, cultural, lingual—are in part responsible for this lack of representation. Additionally, due to patriarchal structures, many of the Kurdish works and anthologies translated into English often predominately showcase male writers, pushing female Kurdish writers even further into the margins (or off the page entirely).

So, this book, focusing on female Kurdish poets is one of the first doing what it does—and doing it well. There is no other collection like it right now, truly, that offers a full book of poems showcasing Kurdish female poetry. Women’s Voices from Kurdistan offers selections by intergenerational women spanning across time and translated from various Kurdish dialects (including, Sorani, Kurmanji, Bahdinani, and Gorani). The book’s introduction offers further insights into the context surrounding Kurdish literature, translation, process, and representations of Kurdish female writers.

This book stands out not only because of its project and representation but also for the outstanding quality of the poems. When we talk about translations, we often talk about how the poem shines beyond just being a translation. We look at the artistry not just the concept of the product. And the poems in this book transcend the concept, offering gorgeous writing from its poets.

Aside from delivering new perspectives, one of the best things about reading poetry in translation is discovering uncommon and exciting language patterns—new ways of articulating. It is being awed by dazzling lines and enchanting phrases; seeing and hearing language and syntax that subverts what one typically encounters in poems written in English. In Women’s Voices from Kurdistan, the reader will find talent in the poetry and poetics. Poetry, I believe, translates the human experience. And great translations offer up a delight in the poetry and poetics of the human experience.

I will provide a few examples. Take for instance these beautiful lines and soft rhymes which support the speaker’s tenderness in MestÛre Erdelan’s elegy for her husband, titled “An Elegy for Khosrow:”

My Khosrow, spring is here;

how I wish it would not have come this year,

that no sprouts would have sprung in the garden,

no trees would have come into buds,

no nightingale in the meadow,

no dew on the petals.

The speaker aches for her husband. Seeing spring blooming—all around her signs of life and new life everywhere— she laments his death. It would be better if spring had not come at all. And really it’s the soft rhymes (“here”/ “year” & “meadow”/ “petals”) that help to successfully convey that pain and tenderness through the poetic craft. The rhymes hold the reader. The rhymes carry the grief.

With equilibrium, in this collection, the reader gets a glimpse into the reality of Kurdish female oppression and suppression, as well as female empowerment and strength. There is a balanced range throughout the book—it is not just “one-note.” Women’s Voices from Kurdistan conveys variety in perspective, experience, and representation of Kurdish women. It does not paint all Kurdish women as the “same.” It doesn’t just present Kurds and Kurdish women as a monolith but rather offers a breadth of voices and experiences ranging in theme. There are poems of loss and of love, of questions and wisdom, of vulnerability and empowerment, of ancestral memory, familial longing, and joy.

In this next excerpt, we see just one example of the way voice comes through with incredible strength. Voice is the backbone of this poem. Here is a stanza from Trîfa Doskî’s “Symphony:”

Part 3

I am a translucent woman like basil’s leaves

in your novels

and in your poems

I hand you the key of the city

So the book may lose its purity in your hands.

Undress the book from its letters,

Turn it into wine

Give it to the birds, so they can dance full of desire.

The stacking of imperative commands in the end conveys the speaker’s firmness. The speaker pushes against the beloved’s representation of her as a soft sketch of a woman. She then takes control and power handing over the key of the city and commanding: “Undress the book,” “Turn it into wine,” “Give it to the birds.” In this collection, we see poems of female power and agency, which is important to give the reader a sense of the fullness and variety in the lives of Kurdish women.

Another example is in Diya Ciwan’s “The Needle,” where the speaker transforms the domestic sewing tool— which can be seen as a symbol of distinct gender roles— into an object of power in her hands. Ciwan writes:

So much, this needle has done!

With her tiny body, she did the work of a ploughshare.

With her delicate tip, I sewed shut

the mouth of hunger,

and buried destitution.

She’s my heavy weapon,

sharper than a dagger,

handier than big words.

The needle is both a means of creation (and therefore power) for the speaker and also a symbol of Kurdish female strength. “With her tiny body, she did the work of a ploughshare” can also be read as commentary on Kurdish women’s formidable strength and resilience. Sure, “tiny” and “delicate” but also provider, fighter, and healer.

Finally, as another example of skillful use of poetics (and my favorite poem in the collection), Jîla Huseynî uses metaphor and imagery in the poem titled “Question” to articulate the magic and meaningfulness of her matriarchal lineage. The poem’s speaker is thinking of the scarf worn by her mother and possibly her grandmother, conveying the way inherited artifacts and items can offer comfort, connectivity, and curiosity. She writes of wearing the scarf and other items:

And my head is an open window to the sky,

Wishing to host the sun at day

And the moon and the stars at night.

My mother also left a pair of pitch-black glasses.

It says: “This is the world as you see it.”

With every thunderclap, a mushroom of a hundred questions

Old and new sprout in my eyes.

As a daughter of diaspora myself, the daughter of a Kurdish woman who came to the US as a refugee, as a Kurdish-American poet who is not able to read Kurdish, I am so grateful for this collection and the work these editors have all put into this powerful project. I read the poems over and over. There is much more forthcoming from Ghaderi, Yucel, and Ali—who work with great care and ethics, considering the politics of translation. As other literary curators, translators, and writers showcase Kurdish literature translated into English and shine a light on Kurdish female writers, we can look to this book as laying a foundation for the future of this long-overdue, transformational work.

Holly Mason Badra received her MFA in Poetry from George Mason University, where she is currently the Associate Director of Women and Gender Studies. Her poetry, essays, reviews, and interviews appear in The Rumpus, The Adroit Journal, Rabbit Catastrophe Review, The Northern Virginia Review, Foothill Poetry Journal, UA Poetry Center Blog, CALYX, So to Speak, and elsewhere. She has been a panelist for OutWrite, RAWIFest, and DC's Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here events as a Kurdish-American poet. Holly is currently on the staff of Poetry Daily and lives in Northern Virginia with her wife and dog.