An Interview with Mark Wunderlich

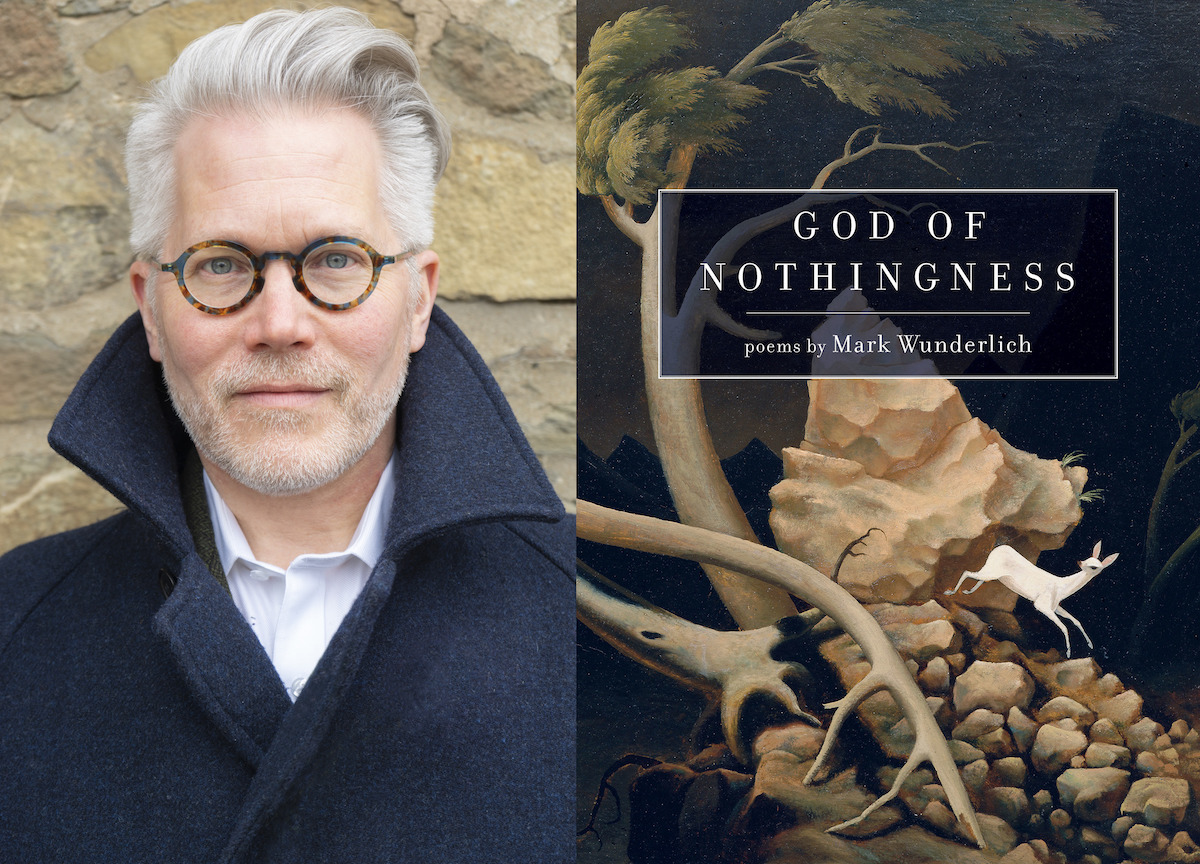

Mark Wunderlich is the author of four collections of poems, the most recent of which is God of Nothingness, forthcoming from Graywolf Press in 2021. His other collections are The Earth Avails, which received the Rilke Prize, Voluntary Servitude, and The Anchorage, which received the Lambda Literary Award. He has received fellowships from the NEA, the Amy Lowell Trust, Massachusetts Cultural Council, Civitella Ranieri Foundation, and the James Merrill House, and his poems have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Poetry, APR, The Nation, The New Republic, The Believer, and in over 40 anthologies. He is the director of the Bennington Writing Seminars graduate writing program, and he lives in New York’s Hudson Valley. More information about the author can be found at www.markwunderlich.com.

Jon Riccio: Thank you for your time, Mark. It’s exciting to interview you before God of Nothingness’ official publication. I’ve enjoyed your collections and essays, especially “Where We Write” (Poets & Writers, March/April 2017) in which you emphasize that “Writing well, making complex art, and having a life of the mind differs from achieving public recognition.” I’ve returned to this often during my PhD program in Mississippi, whose weather is nearly an equator removed from the Scandinavian climes in the book’s “Five Cold Stories.” God of Nothingness’ revelations crescendo to “Midsummer’s” core—“My future is the only future, my past a story or a scar, // a body, a book, a bed to rest my head in.”

That future originates in the opening poem, “Wunderlich,” a list stretching back to medieval Germany—

The name means “odd.”

The name means “queer.”

It can denote an “odd fish.”

It suggests a “queer chap.”

Sometimes it means “capricious.” It can also mean “peevish.”

It’s a synonym for “singular.” It is thought to be poetic.

The Pied Piper of Hamelin was called ein wunderlicher Kauz,

with his colorful clothing come to pipe the rats away.

It flows from definitions to attributes—

It means “he loves Christmas like a simpleton.”

It means “makes sushi out of SPAM.”

The name means “curious,” as in “he bought a haunted house,”

The list concludes with “a pagan’s ashy grave atop a limestone bluff / where the wind speaks his strange name or worse— / voices recognition, an attribution, or a curse.” Acknowledgment pairs with meditation on the family name to operate as a catalog of modes and means for moving through the world. Is this catalog central to God of Nothingness?

Mark Wunderlich: Thank you for taking the time to read the book and to formulate questions. This is the first interview I’ve done for this publication, so I’ll be finding my sea legs as we go. Jumping right in to the question—one day it occurred to me to write a poem about my own name. My last name is often commented on, as it is unusual, obviously ethnic, slightly obscene, and as an adolescent it gave rise to terrible teasing—and this among schoolmates with names like Bublitz and Kochendorfer, but still. When I first went to Germany, I was excited to be in a place where my name would make sense to people, and where they would know how to pronounce it. It turned out that the name is unusual in German as well. An Austrian friend of mine once said to me that I must have had some interesting (or peculiar) ancestors, given what my name means. The poem arose out of a kind of meditation on the idea of inheritance, on what we receive from our forebears—good or bad. I don’t know that the list of attributes is actually central to the poem, but the conclusion is, ending as it does on the death of a child whose grave is back on the family farm in Wisconsin—a place that is now lost to me as well.

In 2018, eight people I was close to died, including two important poet-mentors, relatives, a close friend, and eventually my father. Prior to that, a long relationship ended and I found myself alone in an old house in the countryside. My nephew had committed suicide a couple years prior. I was given the task of selling the family farm in Wisconsin where my family has lived since the 1830’s. These losses just kept happening, and I found that writing poems helped to give those experiences some definition, a shape, and language. Lines, rhyme, sentences—these were all tools I used to place my grief into some artistic context, as part of a lived life that could be narrated and spoken, as opposed to becoming another occasion for falling into a depressive void. I don’t actually think writing poetry is a very efficient therapeutic mode, and I resent any efforts to buckle poems in that harness, but I can say that the process of writing made these losses bearable.

JR: The couplets in “A Driftless Son” aid in generational threading—

It came to me to sell the family farm,

shift its failures to a man who planned

to occupy the place for recreation,

to hunt the deer that spook and shadow in the pines,

my job to consign to another my granddad’s stunted grove

of walnuts planted—against the forester’s advice—

The uniformity of construction is how I imagine a land deed to look, goodbye to a pond’s “manurey slurry” and “the Tulius brothers’ hogs.” Couplets occur in a number of the collection’s poems. What aspects of this stanzaic unit do you find most appealing?

MW: I have used a lot of couplets in my poems throughout my four books. I love the slimness of them, their refinement. When I see a poem in couplets, I can relax and read the poem. (Sometimes I see poems written in big formless, airless blocks, and I think I don’t want to go in there, I’ll suffocate). Roman poets created the form of elegiac couplets, and these were used to address subjects not suitable for heroic and epic forms, and so I think of couplets, to quote Eavan Boland, as “a particular dialect of the Underworld.” The poems in this book are mostly in the elegiac mode, so this made sense to me.

JR: These lines of “Ha Ha Little Hunchback” bring to mind Anne Sexton’s segues in Transformations where discomfort and relationships comingle—

His teeth pinched so he didn’t wear them,

his idea of a lady’s gift was a meat slicer he knew

she’d have to wash, but who wouldn’t want to ponder

a moon of pink baloney slipped fresh into an outstretched palm?

When I think of Sexton’s ascent, I recall her time at the Antioch Summer Writers’ Conference where W.D. Snodgrass became a significant mentor; “In seeing you, in feeling your marvelous restrained sense of immediate loss, I saw my own loss in a new color,” she once wrote to him. Such nurturing dovetails with your poem “Gone Is Gone” for Lucie Brock-Broido, which admits

I didn’t know how much of me was made

by her, but now I know that this spooky art

in which we staple a thing

to our best sketch of a thing was done

under her direction, and here I am

Familiarizing myself with Lucie Brock-Broido’s work, I came across her poem “Almost a Conjuror,” this excerpt resonant with the abovementioned “spooky art”—“He imagined he could move a broom if he desired, just by wishing / It. If he spoke of ghosts, he thought he could make of art vast // Tattersall & spreading wings.

What do you value most about Lucie’s mentorship?

MW: It’s difficult to summarize what she meant to me and how much she changed my life. She was truly an extraordinary, generous, obsessive, dedicated, gifted teacher, but she was also a complicated person—like all of us I suppose. When I was choosing which graduate program to attend back in 1991, I had read The Good Thief, by Marie Howe, and A Hunger by Lucie, and I fell in love with the minds that made those two books. They are extraordinarily good first books, and I decided that I wanted to learn to write a book like that, and since both studied at Columbia, that’s where I went. In my second year at Columbia, Lucie was hired, and I remember attending her interview talk, and feeling as if I had conjured her. Here was this person whose book had entranced me, and now she was going to become my teacher. From that point on, I stuck to her like a tick.

There’s a lot to say about how and what she taught, her beautiful and obsessively assembled teaching anthology, the categories of poems she created, each of which illustrated a conceptual or technical aspect of poetry. She taught technical skills, but her vision was larger than that. The most important thing I learned from her, though, was about the sacrifice of poetry and the life of a poet as a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk, or complete work of art. Everything about Lucie’s life seemed to be oriented around the making of poems. She carried her books with her at all times, she wore clothing and shoes she had made according to her own designs and specifications, and which reflected some inner poetic or literary fantasy. She bent the world to her schedule and to her will as much as possible, and she did it all in service to poetry. It was an enormous undertaking, and a tremendous sacrifice, and I think that as she aged the great aesthetic artifice she maintained so assiduously began to wobble and to crack a bit, and in her last poems, one sees her ask questions about whether it was all worth it. Of course the place she asked those difficult questions was in her poems, and that is what makes those poems so good, and also so heartbreaking. To answer your question directly, Lucie showed me what the stakes were for being a poet, that it might require everything one has to give, and that one might have to give up a conventional life. The reward was the experience of making poems, the process of bringing the interior life out into the light and assigning language to it. She treated that process as a mystical experience, and being alive inside that process could be something one might live for, a force powerful enough to build a life around and give it meaning. Besides being my teacher, we became friends, and so we grew beyond the relationship of a teacher and a student, and I guess I’m still mourning her. About two weeks before she died, she called me on the phone, and she let me know this would be the last time we spoke, that she was dying, and that if there was anything I wanted to say to her, this was the moment. I was in my house. It was March. I had a fire in the wood stove, and the room was dark and quiet, and I told her what she meant to me. It was a gift to be able to say those words to her, and I’ll never forget it.

JR: I appreciated the variety of rhymes in God of Nothingness, particularly the closing lines of “The Prodigal”—

the birthday check, while we imagined him as some wreck

sleeping on a bus. We. All of us.

And so he returned, welcomed warily by our dwindling clan,

to shake his dying dad’s hand. Here I stand

in the background, frying the fatted calf in grease,

while he weeps for what was lost—for himself—

and with evident enviable release.

Here rhyme is playmate to gravitas, and the alliteration of Fs in “frying the fatted calf” diffuses solemnity ever so much. Rhyme in “The Bats” accelerates from the antepenultimate tercet on—

around blue outlines of pines,

pitch up over the old Dutch house

we share. They scare some

but not me. I see them

for what they seem—

timid, wee, happy or lucky,

pinned to the roof beams,

stitched up in their ammonia reek

and private as dreams.

Some poets, such as Gwendolyn Brooks, are rhyme-rich—

Think of sweet and chocolate,

Left to folly or to fate,

Whom the higher gods forgot,

Whom the lower gods berate;

Physical and underfed

Fancying on the featherbed

What was never and is not. (“The Anniad”)

whereas the title of Matthea Harvey’s 2014 collection, If the Tabloids Are True, What Are You? uses rhyme to query identity. The poems where I rhyme are ghazals and villanelles, but I’d like to branch out, God of Nothingness one of the collections helping me reach that decision. What are your thoughts on rhyme?

MW: I can’t think of any other part of writing poems that feels more magical to me than rhyming. Rhymes make a poem incantatory, transform it into a kind of spell. The feeling of writing a poem and working into that moment when the poem begins to sing, when the gear of one word locks into the cog of the next, and the whole machine begins to turn—there are few experiences I love more than that, and the hope of inhabiting that state once again is what makes me keep returning to the page and to my desk. I should mention that many of these poems were written in a period of dramatic and rapid composition when I was writing one or two poems a day for weeks. It felt like demonic possession, or divinity, or maybe a bit of mania or madness, and all I want is to return to that state when everything I saw, all the material world around me, all my memories, all the poems I have read and absorbed and love, all the art I have seen, the people who shaped and made me, the languages I know—all that was alive and graspable, and every day I funneled that into my pen and scratched it into a big red notebook. Being in that state of vivid embodied poetical connectedness in which I had access to all parts of my subjectivity—I feel like that state—rare, granted only after years of work and study and discipline—was a state in which my selfhood was breached, and something else came spilling over the top. When people speak about meditating for days and days, and entering a state in which one sees the connections between things—that was the state I was in last summer as I wrote these poems, and I only hope that I have that experience again in my life. Nothing compares to it.

JR: “Shanty” and “Once Forgotten” transported me to a Richard Hugo realm. The former poem’s “shack abandoned in a swamp” (“No one remembers what became of the people / in the house now swaybacked in the marsh—”) evokes Hugo’s “Between the Bridges”—“These shacks are tricks. A simple smoke / from wood stoves, hanging half-afraid / to rise, makes poverty in winter real.” Hugo’s denizens deposit their money “Not in banks, but here, in shacks / where green is real: the stacks of tens / and twenties and the moss on broken piles.”

In the prose “Once Forgotten,” an elderly woman’s caregiver nature (“When we needed a puppet

she sewed us a puppet, when we were sick, she fed us peppermint schnapps.”) competes with senility (“And when she forgot she forgot all of it—”). Before its onset, her presence as a surrogate grandmother mirrors Mrs. Noraine in Hugo’s “A Snapshot of the Auxiliary” (“Russian, kind. She saved me once / from a certain whipping.”). Mrs. Noraine’s emergence from “the sadness of the Dakotas” parallels your Wisconsin woman whose pragmatism is matched by her maternal outlook for all (“She fed the water snake who lived in the boathouse, flicking him little stars of meat which he rose up to catch, his body black as the night’s shadow.”). Do you see additional elements of your poetry in aesthetic conversation with Hugo?

MW: I remember when I first read the two poems by Hugo I keep returning to—“The Lady in Kicking Horse Reservoir” and “Degrees of Gray in Phillipsburg.” I might have even swooned. They were so deliciously gloomy, gothic, private, funny, American, and Western. Based on my love of those two poems, I have often found myself telling students to not be the hero or the victim of their own poems, and I think that’s what I love about Hugo; even though the speaker in those poems is wildly self-pitying, which is unpleasant to spend much time with, he counters that with music, with bitter humor, with psychological leaps that are thrilling. Having poems you really know and love and that become part of the furniture of your interior life is a necessity for writing poems over a lifetime. I think you can get lucky when you’re just starting out and fly by the momentum of your own exuberance and the world’s keenness for the next new thing, but that won’t last as you go ragging into your middle years. That’s when you need to rely on an education which—one hopes—has helped the poet build up a library of understanding and affinity which provides examples of how to be timeless, as opposed to merely contemporary.

As to your questions about other elements that link me to Hugo, I suppose my Americanness? That I’m essentially a poet who has written about rural life? In his poems Hugo’s speaker is often an outsider, and I suppose my own queerness makes me that. (I think queer poems of rural experience are just being written now for maybe the first time, if you consider Whitman an anomaly, as he was also the quintessential poet of the city). That my nature, like Hugo’s is essentially melancholic, rather than sanguine or phlegmatic? Perhaps establishing those connections is someone else’s job.

JR: Section One ends with “Cuthbert,” a poem about a lamb you raise then exhibit at a fair, your work paying off when “The auctioneer sang the money from the crowd.” The next morning you come across the carcass—“His head looked out at nothing he could see. // Cuthbert, little Cuthbert, you have left nothing for me.”

In Section Two’s first poem, “My Night with Jeffrey Dahmer,” you are the potential Cuthbert “in a bar,” an apologetic Dahmer “asking my name which I withheld, / my name which I keep lodged between my teeth.” You tamp disclosure, only revealing your name as the poem’s third-to-last word. Dialogue and assumptions (“—some farmer’s son— // a bit out of date, stuck as he was in the country,”) safeguard the poem from metonymy associated with Dahmer. What other techniques should poets writing about brushes with infamy employ to prevent their work from collapsing into sensationalism?

MW: That’s an interesting question, though since Dahmer was the only serial killer I have met (that I know of!) I don’t have much to compare it to. That poem came about after a lunch conversation I had with Amy Hempel and Bret Anthony Johnston—both fiction writers. We were trading stories about brushes with danger, and I recalled the time in the early 90’s when Jeffrey Dahmer bought me a beer, and they really drew out the details, and this conversation led me to understand how fiction writers construct a larger story out of a small, memorable detail. They both asked if I’d written about this encounter, and I had not, but even as I left the table I was starting to compose the poem in my head. I think what I wanted to do was to describe the totality of the experience I had with him—which lasted about as long as it takes to read the poem—and to reconstruct that encounter—which, to be perfectly honest, I can barely remember because it was so inconsequential. Your question suggests that the poem doesn’t traffic in sensationalism, but I think it probably does. The title is definitely meant to bait the hook. I think it’s important to keep poems from being didactic, or from being preachments, or from telling an audience what it already knows. Everybody knows Dahmer was bad—you don’t need a poem to tell you that. Before you go around making proclamations about other people, a better poem is probably found in the exploration of your own contradictory impulses, your own ugliness or foolishness. I think this poem captures something of my own (now lost) youthful arrogance, but also my cluelessness.

I recently read a statement by a young poet in which she said she wrote her books because “she had something to say.” I’m still thinking about this phrase in relation to poetry, and I wonder if this is an aesthetic difference, or just a completely different understanding of what poems are, but I write poems primarily out of a love of language and the desire to engage with language in satisfying ways. The least interesting thing about a poem is its subject, and entering into the process of writing a poem with “something to say,” seems like a way to cut off discovery and accident as you create rhetoric to prove a point, to deliver a sermonette in the form of heightened speech, or to display oneself as a kind of victim-hero of some circumstance for which you seek the sympathetic embrace of an audience. If you’re not engaging in ambivalence it’s unlikely you will manage to get yourself out of the way of the poem, which is the point—to transcend the self and give the poem a fighting chance to traffic in the eternal, and to do that one needs to remain vulnerable, to be open to what is both beautiful and ugly in the world, but more importantly, to remain open to what is beautiful and ugly in yourself. People tend to grossly overestimate the importance of their own thoughts, which they naively believe are original to them. What IS original is the interplay of all one knows, one’s skills, one’s education and aesthetic affinities and the language in which the poem is composed. That combination is unique to every writer, and that is what makes me want to keep reading. I don’t read poems because I want someone to teach me some obvious and tiresome lesson, or reaffirm some commonplace belief, and I don’t write poems to garner sympathy. A poem is a complex, individual work of art—like a dance, or a piece of music, or a painting, and in that way it should be bigger than the person who wrote it.

JR: On the heels of Dahmer, your titular poem tells us—

To admit my father’s infirmity

would bring down the wrath of the God of Nothingness

who listens for a tremulous voice and comes rushing in

to sweep away the weak with icy, unloving breath.

It’s as if that admission is all the entry calamity needs to make itself a permanent guest.

This god “[whispers] from the warren of my father’s brain.” Insularity, regardless of what form it takes, affords no sanctum. Two poems later, “Death of a Cat” professes, “These are the years during which // I have lost a great deal.” We pivot to domestic insularity—

A man I loved left, and the household

we built together became a private realm

populated by my singularity, the paper city

of my books, and by this cat

who patrolled the thirty-two corners of the house.

Deities have encroached on the human condition since Greek mythology. With the current pandemic, I’ve turned to a Goddess of Insular: reading, writing, and teaching from an apartment in earshot of a mini-field that becomes an evening locale for pickup soccer. What God/Goddess of do we need most? As well, how are you thinking about COVID and racial injustice in ways that guide your current projects?

MW: I don’t actually believe in any deities, but I do believe in the power of metaphors, and the God of Nothingness of the poem you cite, and of the title of the book is a metaphor for death. It’s that simple. For me, the tangible world is filled enough with beauty and mystery that I feel no need to believe in the occult, or to cultivate superstitions. That said, I participate in plenty of seasonal rituals and practices that bind my life to the cycles of the planet in ways that enlarge and energize my experience of the world, and to its animals, insects, plants, birds, geography, weather, and climate to which I hold numerous allegiances. I live in the country, and every day I get to look at the natural world with awe.

The second part of your question asks about my response to the current moment and how my own work might address or engage with it. I don’t know yet. Against my better judgment, I watched the video of the killing of George Floyd. It’s one of the worst things I have ever seen. As he died, he begged to be let go. He called out for his mother. Witnesses implored the officer to let him up, and to stop. One witness is heard to say, “He’s a human being!” What struck me was how casual much of it seemed, how normal. This event becomes one of hundreds, thousands, of such events that have been perpetuated against Black Americans, and that it was filmed is the only reason this act of brutality didn’t just disappear. The demonstrations and also the riots that followed are a long time coming, and sometimes I can believe that this time we will see meaningful change. My better nature wants so much for justice to prevail, and for America to undergo the long overdue reckoning. I keep seeing the video in the way one remembers a nightmare, but of course the nightmare is real, a lived reality for Black people, but also a deep problem in which we are all involved and implicated. In the following demonstrations, we saw dozens of other images of old people being knocked to the ground, or young people pelted with paint bullets in front of their own home, of people hit with clubs, and gassed, rammed by police cars, trampled by police horses. One shows a young man who lost an eye when hit by a canister of gas. I hope that these images are bringing home the horror of oppression and of a state that is brutalizing its own people, and that this will result in radical change, but then I remember that 27 children were shot in an elementary school in Connecticut, and no meaningful change came of that, no national movement to do something as sane as keeping automatic weapons out of elementary schools.

I think, perhaps, the American experiment is coming to an end. We entered into a massive public health crisis in a country in which millions are at risk of going bankrupt for seeking medical care. And the American response has been so incredibly dispiriting. Five months in and we are worse off. We see examples every day of people behaving with incredible selfishness and sometimes with hostility toward common sense. Superstition, conspiracy, and ignorance about basic science are being made much worse by Republican leadership (if you can call it that) who have politicized a health crisis from the beginning, and now even more lives, more livelihoods, more plans and futures are being put at risk. Right now, Americans are trapped, and it’s our own arrogance, ugliness, and stupidity that has put us here, but that doesn’t mean any of us deserved this. A government, at the very least, should protect its citizens, and through incompetence, stupidity, greed, and just plain cruelty, a Republican leadership is just risking all of our lives for a decrepit, hopeless, cynical, amoral ideology that becomes more evil every day.

I also know that no matter what happens in November, a significant number of Americans will vote for a man who has fomented violence against his own citizens, furthered racist and totalitarian views, who envies and emulates the world’s worst dictators and oppressors, and I don’t really want to know people who want that for the world. As a queer person, I do not enjoy equal protection under the laws of the United States, and wouldn’t it be novel to live somewhere where that wasn’t the case? I don’t trust Americans to do the right thing, and I think our country has grown too large and is too unevenly educated and that wealth is too unevenly distributed that we are now more like Russia or China than we are like any nation to which we might bear a more flattering resemblance. Our voting districts are so thoroughly gerrymandered, and there is such widespread and overt voter suppression that the interests and votes of a majority of Americans don’t count. My current family and professional obligations are such that emigration isn’t quite in the cards for me, but my long-term plan is to leave the United States for a country whose values as expressed by their public culture and government are more aligned with my own. Whatever talents or resources I have can be theirs to use. That is, if such a place will admit someone like me from a rogue failed empire like the United States. As a queer person, I have always lived in a kind of internal exile, albeit one that includes places like Provincetown, the Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco, etc.—queer spaces where one can move around freely and forget, for a moment, that one is not part of a vulnerable and often reviled sub-group of the population. We are all part of a nation that is failing, and I am deeply pessimistic about our prospects to recover.

For five months now I have been living at home and limiting the places I go and the people I see. My world has grown very small and has become even more internal. Like anyone who teaches for a living, these months have been full of work as we try to reimagine an experience of education that doesn’t happen in a classroom. With others at Bennington, we started on online undergraduate writing program, and this is now up and running. We also converted our MFA in-person residency to a fully remote event. It has been a lot.

As far as my own projects go, I am at work on a prose book about Rainer Maria Rilke. As I mentioned earlier, in 2018, eight people I was close to died. While living through those losses, I began rereading The Duino Elegies, and I found real solace in these strange, drifting poems with their references to terrible angels, dolls, pitiable bats, Gaspara Stampa, and other specificities that pull up the veil between the material and spiritual realm. In 2019, I traveled to several places where Rilke lived and wrote about them. It was my intention to go this summer to Trieste and the Duino Castle, and to Switzerland where he died, but of course that’s not possible now, and I imagine such a journey will be postponed indefinitely. Instead, I will now teach a seminar on the poetry and prose of Rilke to my undergraduate students at Bennington, and the class is going to take place entirely through the mail—no electronic interface, no video—just the books, and letters mailed back and forth. It’s my hope that the slower, considered exchange of ideas between people will return us to something essential, and I intend to use the letters I write as part of the book. As for poems, I’m writing them slowly. First, I need to clear the decks of other professional obligations and then start making space in my mind and in my days to bring more of them into the world.

JR: I loved the back-to-back order of “Ice Man” and “Museum of Bees.” One is tundra-enveloped—

His hand reached toward the glittering sky,

the mountain’s chilled tongue pressed into his hardening mouth,

and so he went on into the centuries

that went on without him, but which would not let him go.

while in the other,

At the museum of bees, there are no bees—

just the empty boxes of the hives

painted gaily, offered as folk art

and displayed here in this ancient farmhouse—

picturesque on the slope of an alpine meadow,

These pave way for “The Beast of Bray Road”—who resides “near Elkhorn, Wisconsin,” contributing to cryptozoology’s intrigue since 1937—in which curiosity ushers oddity. Lore and the poem’s persona voice (“I nursed and grew on the blue milk / drawn by my suckling urge.”) sustain the strangeness. Bray Road is one of many enigmatic sites in the collection, mystery a fuel for memory. In what ways is God of Nothingness a testament to the preservation of anomaly?

MW: I am fascinated by mummies, reliquaries, catacombs, ruins, lost cities, extinct creatures, the last remnants of cultures that exist for us only in fragments. These act as poignant reminders of our own mortality, serve as a check to the ego, to our vanity. I live in a very old house—about 300 years old—and in every likelihood this house will outlast me and all that I was in the world. It’s hard to imagine the world without us in it, but I think it’s important to do that. As Americans, we keep bulldozing our past, paving over it, but when you go to, say, Rome, you see everywhere how the city is just piled up on top of the past, and whole crumbling chunks of the ancient world show through. Romans seem a lot better at enjoying themselves and their city than we do our own, and I suspect this has to do with their relationship to the past, and the constant, visible reminders of one’s own insignificance in the larger scheme. Enjoy your life, while you have it.

JR: “Five Cold Stories” contains some of the book’s most beautiful writing on human connection. Whether it’s during a conversation between cabinmates—“We boil coffee and make confessions under the Aurora, the sky aswirl with the icy chips of stars.” (“Haukijärvi, Sweden”)—or bodies gathered in a sauna—“The stove is our mother pushing her heat onto us, pouring it onto us, dizzying and irradiating the pink spiders of our lungs, searing the bottoms of our feet, heat and ice, heat and ice, the lake keeps the eye of night at the bottom, the mouth of winter is the hole we climb into, jagged with teeth of ice.” (“Hämeenkyrö, Finland” 61)—enclosure contributes to intimacy.

Epigraphs by Hans Christian Andersen, Swedish poet Göran Sonnevi, and Finnish poet Elias Lönnrot augment the poems’ storytelling qualities. Sonnevi’s “It flew like a little bird / its bright border gleaming” is as graceful (“Hämeenkyrö, Finland” 60) as Lönnrot’s “the boat’s on a pike’s shoulders / on a water-dog’s haunches!” (“Hämeenkyrö, Finland” 59) is decidedly moored. Could you tell us how “Five Cold Stories” took shape, and how you came across Sonnevi’s and Lönnrot’s work?

MW: Some years ago I traveled by myself to Iceland. In Reykjavik, the city was mostly empty of tourists as I was there in November. The weather was terrible—rain and snow most days, and the wind blew all the time. I ate mushy fish and potatoes and wandered the city, swimming every day in a municipal pool heated by volcanic water that smelled strongly of sulfur. I loved the bony solitude of the place, its wet wool and coffee and overheated interiors, but mostly I loved the experience of being completely alone in a foreign city where nobody knew me, and inside this I experienced a feeling of almost complete freedom. I found I wanted more of these far northern places, especially in the winter. The extremity of it made me feel more alive, somehow. I went back to Iceland at least six more times, and spent a winter month way up in the northwest on one of the fjords. Growing up in the northern Midwest, there is a lot of Scandinavian culture still intact. I attended one of the Norwegian Lutheran colleges in Minnesota for a year as well, and part of my mother’s family is Swedish. Iceland felt like a combination of Europe and maybe Wyoming, familiar and foreign. The wide, open mountainous regions, and the treeless landscape dotted with corrugated farm buildings, sheep, and the beautiful shaggy horses felt like something I had dreamed up. One autumn I spent ten days riding horses in the highlands during the sheep roundup, and during another visit I stayed on a horse farm in the south and rode in the mountains and to hot springs and along wide, glacial rivers. I also spent time in northern Finland where I went winter camping with a Sami reindeer herder. We traveled for eight days on sleds pulled by reindeer, pitching camp at night in tents, and sleeping on spruce boughs and reindeer hides. Every day was an exercise in endurance, and it was glorious being around those strange animals, in the deep February snow with the Aurora Borealis putting on a show every night. In Lapland, there were no power lines, little air traffic, no electric lights. I returned to Finland for a couple month-long stays in both winter and summer, and I was in Stockholm with some frequency where I met writers and poets. For several years I read widely in Scandinavian literature, and read many of the major novelists and poets, and I learned some basic Swedish. I made friends in all of these countries and that led to more invitations and opportunities to visit. My curiosity led me, but then friendship took over and that led the way. I encountered those writers during my study of Scandinavian literature, and these poems were meant as travelogues, as lyrical prints of those places and times.

JR: Thank you for your responses, Mark. In the final poem, “To Whom It May Concern:” (inspired by C.D. Wright’s “Our Dust”), we move from a “mop of silvery hair” to

The rasp of the ash pan when you empty the stove

is a bit like my voice, stuck in the chimney like a nest.

You won’t have to know how I procrastinated, of my abiding fear

of snakes, or how I gave terrible presents when I bothered to give them at all.

The collection ends in a juxtaposition of your home state and ethereal perfection—“I was in that storm, blown out across the ice / toward Arcadia. That’s a town in Wisconsin // and not some name for paradise.” Kindness, for me, is a component of “To Whom It May Concern” (“Mostly I played the role of someone who cared”). Earlier you spoke of the elegiac mode. Through what other lenses do you see readers connecting with God of Nothingness?

MW: I don’t have expectations of my readers like that, and I don’t really think that’s part of the writer’s job. I mean, I hope people like my poems, and that maybe someone experiences pleasure when they read them. I write these things and put them out into the world, but it’s always a surprise when someone connects with something I’ve written. Reading is such a private experience, and I feel as though I have spent half my life in a book, which is why I wanted to write books—to speak back to everything I have read. I’m not immune to wanting my work to be acknowledged, or my books to sell—yes I want that, but the primary reward for writing a book is the experience of writing it. I recently fell into a kind of creative reverie, in which I thought my way through a novel I might write. I saw each section and part of the plot unfold, and I knew the setting, some of the scenes. For days I just thought my way through it, and it was so pleasurable to do that, to create this world. I don’t think I’ll ever write that book; I’m not interested in writing it, but this experience was born out of my love of reading and a kind of creative impulse that doesn’t need to graduate to a product. I despair at the careerist world of writers and writing which I inhabit. Being a poet is not a “career.” Prizes aren’t fair. Good work is sometimes neglected. Academic jobs are jobs and not rewards, and many of the poets whose names are on readers’ and students’ lips will stop writing and disappear in just a few years. Learning to manipulate a corporate algorithm for followers isn’t a form of meaningful success. Writing poems is deeper and more important than that, and a poet is not a machine whose job it is to produce a product. Composing a poem is a religious experience for me, and there is a central and fundamental energy in that activity that is wholly mysterious, unnamable, and infinite. When and if my work does find readers, it will be their job to forge points of connection and choose the lenses through which they will view the work—if that is what they have the inclination, capacity, and desire to do.

Jon Riccio is a former Poetry Center digital projects intern, and University of Arizona graduate. He received his PhD from the University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Writers. His first collection, Agoreography, is forthcoming from 3: A Taos Press.