An Interview with Veronica Golos

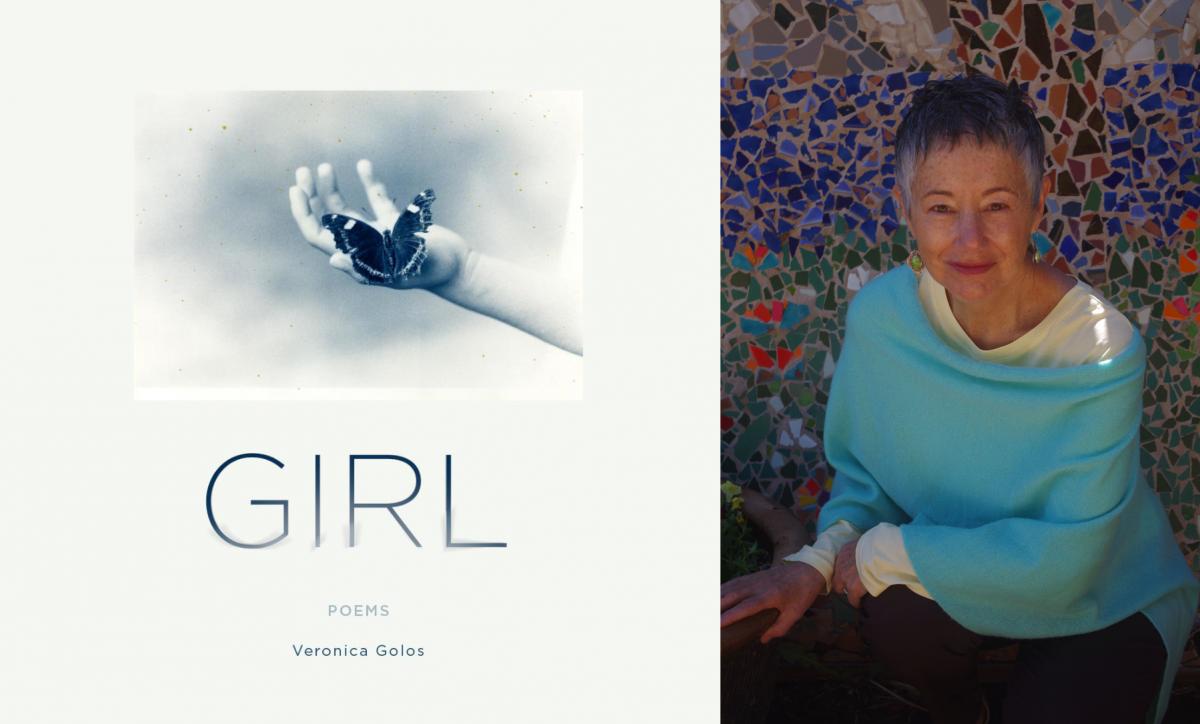

Veronica Golos is founding co-editor of the Taos Journal of International Poetry & Art, former poetry editor for the Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, and core faculty at Tupelo Press’s Writers Conferences. Golos is the author of four poetry books, GIRL (3: A Taos Press) awarded the Naji Naaman Honor Prize for Poetry, 2019 (Beirut, Lebanon); Rootwork (3: A Taos Press, 2015); Vocabulary of Silence (Red Hen Press, 2011), winner of the 2011 New Mexico Book Award, translated into Arabic by poet Nizar Sartawi; and A Bell Buried Deep (Storyline Press, 2004), co-winner of the 16th Annual Nicholas Roerich Poetry Prize, adapted for stage and performed at Claremont School of Theology, Claremont, CA. Golos has read or lectured at Columbia University’s Teacher’s College, Hunter College, Juilliard School of Music, Regis University, University of New Mexico, Diné (Navajo) Technical College, Kansas State University, Transylvania University, and Colorado (Pueblo) University, among others. She lives in Taos, NM, with her husband, David Pérez.

Jon Riccio: Congratulations on GIRL receiving a 2019 Naji Naaman Honor Prize “awarded to authors of the most emancipated literary works in content and style, aiming to revive and develop human values.” This criteria is as wonderful as it is appropriate. I enjoyed the seamless manner in which your collection travels from the environs of Little Red Riding Hood to New York City of the late 1950s, skimming briefly the East River. GIRL fosters a language genesis of “Motherspeak” and “Daughterspeak,” the opening VOCATUS ATQUE NON VOCATUS DEUS ADERIT (Bidden or not bidden, the god is present.) like a banner affixed to the plane of these poems. “Rougedwoman: Prophecy” begins in knowledge res—

What I know is more than thorn

and thistle, whistling through

the oak forest, trees large as barns.

What I know is Wolf,

and that cannot be reckoned;

for I have been inside

Him, and have seen through His gold eyes

and smelled the world.

Shifting Little Red into the adult-tense (“I was the girl. That much is true. Not innocent, / but virgin. We make too much of innocence.”) gives Rougedwoman testimonial, which survivors of fairy-tale traumas sorely lack. How do personae and empowerment through the Confessional mode function in GIRL?

Veronica Golos: Thank you Jon for your interesting questions and interpretations. I have found we always learn from a reader/reviewer/interviewer. Of course this poem, “Rougedwoman: Prophecy,” is a persona poem in the voice of Red Riding Hood retelling the fairy tale, from— almost literally—inside the story. She is an old woman now, recounting her own version of her renown experience. The Wolf—as a being that has been hunted, made into a fearsome being, she turns into an animal god—and being inside him, a play on a male figure giving birth in a sense, or rather holding the child, protecting her—an ancient god if you will. She sees a future, a kind of prophesy for us to heed. I think that for me is the joy of persona—the retelling from the inside, from the “non-official” tale.

Within the old gods, the Girl of this story shall be made whole. The recovery is in revelation, and surviving, I believe.

JR: Deities permeate the text. Jack Gilbert’s epigraph “I imagine the gods saying, We will / make it up to you. We will give you / three wishes, they say” assuages the speaker so that

I did what they prompted, made my way through

the warren of my mother’s madness, tangled my long braids

with ribbons in talisman colors of ruby and white.

The gods would nudge me in sleep, singing their songs,

urging rest between battle. They’d give me a new name,

recount the days I’d lived, slip me the heart of someone’s

daughter. Eat, they’d say, be strong.

I can’t help but think of talismanic consumption. I’m also interested in whether the relationship of sybil to oracle is crucial to GIRL.

VG: Thank you for bringing this Sybil-Oracle connection forward. In writing about or inside the self, I think many poets find room in the myths of their cultures. In addition, at the best of times, we find we are writing as if we are being told the words, the lines—a kind of sybil to our own work. This Girl is a character who has heard the whispers of gods inside hers, both as aid and as a kind of bedevilment, a feeling of restlessness. As I look through my other three books, there is the constant thread of the inner voice, whether it is in Abram/Hagar (A Bell Buried Deep), or the “witness-from-afar” to the Iraq war (Vocabulary of Silence), or the Protestant God of abolitionist John Brown (Rootwork). I think one of the themes of GIRL is how the inner self, the voice of survival, of purpose, of a place that cannot be touched or reached by another, but through poetry perhaps, can save her.

JR: The five-part “Playground, New York, Circa 1957” casts its last segment as a one-sentence prose poem over twelve lines. Such energy perfectly mimics “the park [flooding] with children like a flock of goldfinches in the warm buttery light.” On this leg of the Girl’s journey “the gods back away leave her to have this for later for memory’s sake.” Just compensation, as she was their “Icarus link / between the (un)coupling of worlds” in section three. It’s interesting that you chose one of mythology’s doomed males, as if a reversal on the Tiresias story, whom Hera changed into an oracular woman. Does genderfluidity play a role in GIRL’s mythos? What can the Girl learn from Tiresias that New York fails to teach her?

VG: The genderfluidity idea is so very interesting. Not so much ABOUT it, but the poems do switch the original stories’ genders at points—genders and their story. I would think, now that you mention it, that Icarus as Girl, is a link, and holds worlds, the inner and outer worlds of which we spoke previously, and—earth and sky—together, as well as the link between the city playground and “her voice of sweetwater.” The magic of the split-second when everything goes silent, as if in agreement. She does hold—arms outstretched—these various worlds, the world of the ancient gods and this world she is in, in the playground. I do appreciate your bringing the Tiresias story as yes, I think of the Wolf as male, and the Girl, sharing one body, one inside the other. “Each Wolf has a girl inside.” And of course, I am using different Greek myths throughout GIRL, as you have noted later.

Of course, being the Icarus link is also temporary, really in this moment of suspension in the playground, until the “jumbling chaos of this world falls all over her . . .”

JR: “Confluence” features a recurring dream of a pond and that gorgeously worded “purse of sand / leading downward.” Serenity seems attainable, though “I question this. Its perfection. Am I remembering a / remembering?” Time is an opponent of recollection/reflection, the latter tied to the Narcissus aspects of this poem—

or is it me, a facsimile

of me?

The lake is not emerald, not that:

no, it’s the hush

of depth –

How did you achieve a balance of beauty, ambiguity, and memory that allows for poems such as “Confluence” to work as well as they do in a collection whose events unfold more than sixty years in the past?

VG: Here, I was thinking not only about this particular memory, but memory as a whole. Memory of course here in this book is almost timeless—the old gods, right through to the present-day memory, in “Pas de Deux.” The “Prequel” at the end of the book, is an even earlier time in the Girl’s life. But memory shifts, as dreams do. Some are seared into scars, some, like the memory in “Confluence,” are true, but true in a more complex way. I wasn’t thinking so much of the Girl looking into the water, but her merging with it, and how both the water and the memory hold her. Although, still, she is mute.

JR: The theme of submergence continues in “Ten Miniature Gods Swirl Inside the Room”—

Do you dream of us?

Sometimes.

When?

When I’m under water. In the bathtub. I go

under water, and I open my eyes, and there

are so many floating sparkles.

Will you come with us?

Where?

Where do you wish?

To the sea?

You will become

Mermaid.

Oh yes, please.

The bathtub is nautical planetarium, the sea a site of trans-species metamorphosis. The preceding poem “East River Elegy, New York, Circa 1960” ends in “salt, crust, grit. those diving bodies.” Has water’s aesthetic been a constant in your poetry, or was GIRL the advent of its importance to your work?

VG: I just love your take on these poems! “The bathtub is nautical planetarium”!! Thank you. Well, you know I grew up in Manhattan, New York, an island, surrounded by water. I do think as you suggest, that GIRL was the advent of the use of water—pools, ponds, rivers, bathtubs, etc. as an aesthetic and yes, it seemed to come to so many of the poems. I live in New Mexico, and the Rio Grande runs through, through the landscape and us. Also, the mermaid image, the ability to be in two worlds, I think repeats throughout the poems. The submersion is her inner life; and yet, is she imagining these little gods, these voices? Or, as in childhood, are they there, in the same way the Girl could fly?

JR: The narrator in “Calving Ice: Snow White & the Queen” imparts her belief that “Each woman . . . is a queen taken apart; / reassembled.” She endures “a corset of glass; / my waist a tinder box.” What would the talking mirror of GIRL articulate about poetry as pain repository and the nuances of a reparative “I”?

VG: I meant there to be two narrators, the young girl who grows into her beauty from plainness, and the Queen, whose beauty is fading, both speaking from behind the mirror. Yes, the poem is also a mirror-speak poem, right out of the fairy tale. In GIRL, there are a number of pairings, sisters, mother-daughter, wolf and woman. Here I thought to deepen or release the story, so that both see the danger of being beautiful (which is picked up later in “Motherspeakbecause”), of that being all that is seen about them—as Snow White says, “I know the hunger / beauty creates” that is in the eye of the beholder, whether it is another, or the self. The wholeness comes with knowing this.

JR: I loved the backwards text in “The Snow Queen (M)Other Writes to Her Maker from Behind the Page.”

?em edisni nettirw si hcum woH

How much is written inside me?

.ria otni ekalf I. wons fo namow A

A woman of snow. I flake into air.

Yemeni-American poet Threa Almontaser employs a similar effect in her poem “Heritage Emissary,” though it’s only her word order, right to left (as Arabic is read), that reorients our experience, versus letter transposition along with lines reading right to left. What led you to this craft decision that, when tried in my own work, took your command “noitpecrep ebircsni / inscribe perception” to heart?

VG: I thought of the Anderson story, “The Snow Queen,” and how he had portrayed her—she is made a cold person, a stealer of children, a kind of Lilith character, made of ice. This is what she is questioning, and also she is questioning the role of narrator, of creator and his language. I think of the Tempest, and Prospero’s use of language to control and burden Caliban. Also, of course, in the title, Other and Mother are blended. The speaker is behind the page, graduated from a mirror to a written page, yet, a prison for her, behind the page. It is meant to be a co-poem with “Calving Ice.” And, this Snow Queen also, of course, is the maker of another language.

JR: From a lexical standpoint, “Motherspeak” favors repetition—

Out of me – out of me.

You always wanted out of me.

Sorrow was never enough –

nor terror – that stark branch – its black bulk

always at the window –

the Aegean, again and again

Its evolution, “Motherspeakbecause,” dwells in anaphoristic domains—

Because held

in my father’s basement

he’d offer a tin

a jack-in-the-box

Because my hair of coal-ash

my mother’s fox red hair

Because this:

I was beautiful

Because men

they

always

found

me

The initial appearance of “Daughterspeak” language is floral-tethered, nature its primer—

The sunflowers have crumbled. Fields of them, swaths of yellow, gone.

Now the asters’ lavender is strewn across our hills.

Still, in the mountain, the forest, aspen tremble into gold.

Autumn. A ghost in my garden, water-colored,

a tidal ripeness. In blueness, a rough wind swirls;

I sever to the stem: lilacs, roses, poppies, the wild hollyhock.

It takes a pathological turn (in the medical sense) when next encountered—

She is residue, sperm-colored, and the stink of her

is ox blood, a wound left untended; I shudder. Her hands are nettles

and hook. (“Daughterspeak: A Haunting)

I can parse the tonal relevancy each has to New York of the mid-20th century, and am curious as to which language would best thrive in NYC today. Is there another language built on these foundations that informs the poems that come after GIRL?

VG: You are a very interesting and interested reader of poems. I think of these poems, the Mother-Daughter poems, as prisms, not simply of one pair, but how complex that relationship can be. I had meant, or at least was thinking about the iconic Demeter-Persephone coupling in “Motherspeak.” Interestingly, at the end of that poem, the daughter, in leaving, is “embedded in earth.” This I see as both a burial, but also a beginning, that is Mother Earth. If, as you have done, we then look at “Daughterspeak,” it is the rise from earth into “the ink-blue artery // of my throat.” That is to speech to self. And your idea of both New York and mid-20th century is accurate: In “Daughterspeak: A Haunting,” I am both thinking of the mother already seen in previous poems, but also of war, of the woman “gnawing / chunks of bread while the soldier pounds her closer and closer to stone.” The haunting of the 20th century, and this 21st century.

JR: You paraphrase Sappho’s line “είναι ήσυχο, ή αλλιώς θα σας βλάψει” (It is quiet, or else it will hurt you). at a traumatic moment. I hear her fragmented papyrus in tandem with the speaker’s admission—

So young. How do I tell it?

In the temple, snakes licked my ears.

I

heard

the calculus of what was not desire, but something else.

The pronoun “it” is a fortress of two letters that holds the event’s weight. Into what structure would GIRL translate as a work of architecture?

VG: Wow, what a wonderful question. I would think first, the great ruins of temples in Greece, where you can still imagine the whole. As in “In the temple snakes licked my ears.” This as I remember is spoken by Cassandra, in Euripides’ play, The Trojan Women. Thus the “telling” in this case, about rape, is not heard or believed, as we have seen in our era.

JR: Thank you for your responses, Veronica. I’m grateful for the time spent talking to you about GIRL. Your first collection A Bell Buried Deep was adapted for theatre. The Juilliard School of Music is among the many academic institutions where you’re lectured. Please share two takeaways from cross-genre collaborations that made you a stronger writer.

VG: Well, just off the top, I would think of dance and music of the era of the 60’s through 80’s. Certainly growing up in New York, at a time of upheaval and the opening of cross-cultural arts and thinking, has influenced my poetry—I am a child of the 60’s, of the political promise of those years. In my first three books, A Bell Buried Deep, Vocabulary of Silence, and Rootwork, I explore my wrestling with American history, and in GIRL, I explore my own history.

Thank you for your generous questions and perceptive look at my work.

Jon Riccio is a soon-to-graduate PhD candidate at the University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Writers. He serves as the poetry editor at Fairy Tale Review, and was a past digital projects intern at the Poetry Center.