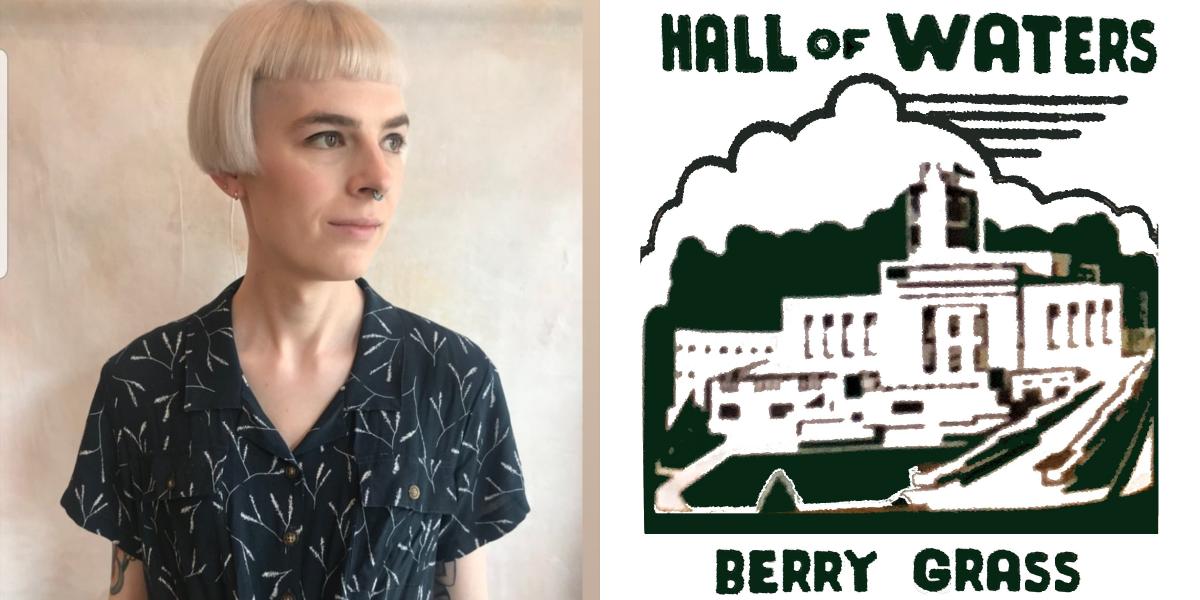

Berry Grass’ new book, Hall of Waters is out from The Operating System. The book looks at the town of Excelsior Springs, Missouri through the lens of transness, deconstructing the settler colonialism of the Midwest, and a series of meditations on the work of one of Excelsior Spring’s most famous residents, Donald Judd. As a fellow trans memoirst, activist, and cultural commentator, I was thrilled to recently sit down and talk about these topics and more with Berry.

ALEX DIFRANCESCO: There are all these moments where you pull back from the big topics you're covering to deliver these gut-punch truths about life, but especially life as a trans person. The first one that hit me was the Al Capone escape slide, and when you realize if you escaped your abusive dad, you'd be leaving behind your mom and brother. "An escape is never as clean as you'd like. You always leave something behind." Stylistically, these are different than a lot of the rest of the book. Did they come from a desire to change mode of thought or sentence style or both?

BERRY GRASS: I think first & foremost that any pulling back happened on an essay by essay basis--where my thinking went for a given piece. I did take into account how those would play when I was sequencing the final manuscript (i.e., generally not wanting too many of those in a row, etc). My project from the start was to try & assemble a linked collection of essays that was about this macro-level demythologization of the rural midwest but was ALSO very personal. Some of the essays titled after water-related sites in Excelsior Springs, MO were directly about me and my life, while some of the essays in that same sequence were entirely research driven. Same with the Judd essays: some ended up being very personal, some were mostly about Judd and Marfa, TX and the whiteness of contemporary art capital. Some were both. Each piece was composed as a true essay, where I trusted my thoughts enough to follow them and lead me to surprising places.

ALEX: Speaking of research, you have a rather extensive bibliography at the back. I think, because of its experimental nature, this book would be really interesting as a digital hyper-text inclusive version -- any desire to create such a thing, or any such thing in the works?

BERRY: No such version of the book is in the works right now, mostly becuase I’m not super techy. For example, I built the historical survey form essays in Microsoft Word instead of something useful like InDesign, because I don’t know InDesign, hahaha. But I agree that there’s totally lots of interesting room for research-backed literary works to use the digital space in more creative ways! With Hall of Waters specifically, I don’t know, for example, the legal barriers that may be in place of using governmental papers (i.e. public documents) for a digital-facing experience of the book that’s being sold at a profit. But really, I do think the possibilities of folding our research into a creatively presented experience is something that nonfiction writers are & should be thinking about.

ALEX: There are a few experimental techniques employed here, like forms and photographs. What did you feel the book gained by this? Do you feel that it lost anything?

BERRY: One of the things I value most about creative nonfiction is the freedom I feel I have to align content with form. I also try in my essayistic practice to be open to form finding me instead of forcing something. The hermit crab essays that use the form of Missouri state historical site survey forms was a form that totally found me. I had been spending months reading survey reports on water-related sites in my hometown, and it eventually dawned on me that I could try to make a hermit crab essay out of that literal government form. I began to think about what tends to merit inclusion on the historical places list. I started thinking then about what it would be like to consider a woman surviving abuse as worthy of historical merit, or a trans kid trying to figure themselves out as something historic. I think the book benefits from those pieces, with their bureaucratic layouts and their photographs, from content and form meeting each other. So much of this book is drawn from extensive research, and so much of this book is about what can be revealed by documentation & what can be obscured by it. I also hope that by switching up the form and styles of narration, it encourages careful reading; there’s so much intense language and intense fact that I don’t want reading it to be “easy.” I can’t say that I feel the book lost much of anything by including these formal shifts. Maybe it’s a book that, for some readers, will synchronize more cohesively on a second read...but to me that’s not a loss, not a bad thing.

ALEX: I really very much admire how you write about race -- not as someone who can understand what it's like to experience racism, but as a white person who is bent on excavating exactly what the construct of whiteness is and how it affects the world. As a white trans writer also greatly concerned with things like race, I wonder if you hesitated at all in this, worried about taking up space that wasn't yours to? Or whether the dissection of whiteness felt like an adjacent project to discussing racism, but one that white people are responsible for?

BERRY: I absolutely think that white people bear a lot of responsibility to talk about whiteness, to identify the ways in which we construct & re-construct whiteness to our benefit, and to ultimately reject and dissolve whiteness. My personal ability to talk about whiteness is hugely in debt to many Black writers and scholars of critical race theory, of course. But I don’t think it’s the responsibility of persons of color to dismantle whiteness, because that’s not how power works in a racist society. Whiteness as we know it can’t be dismantled without white people rejecting whiteness. With regards to Hall of Waters, I could not do the work of demythologizing the slanted narratives that the midwest tells itself about itself without speaking to whiteness. White supremacy is at the core of those narratives. Settler colonialism is at the core of those narratives. And these are narratives that always try to elide white supremacy despite being built upon it.

While I had no hesitation about taking up space (because this is a conversation I think white people should have, because I want white people to reject whiteness, but also because taking up space is pretty endemic to the essay in general, haha), I was trying to be very cognizant of my position as a white person. I didn’t feel like it was my place to write in lyric language about physical violence enacted upon indigenous persons or upon persons of color. I did not want to enact a kind of violence or anti-Blackness myself by writing stylized prose or graphic descriptions of things that did not directly harm me. My intent was to write about anti-Blackness or settler colonialism very matter-of-factly. To correct the record or reintroduce truths or hold the mirror to other white people from my hometown without trying to lyricize events that I can’t know the pain of.

ALEX: You write about and sometimes to the minimalist artist Donald Judd throughout the book. I know from following your work that you not only write about "highbrow" fine art, but about things often considered "lowbrow" like professional wrestling and denim jacket patches (in the interview in the back of the book, for example, you shout out Legend of Zelda, which is huge and mythic, but also a video game). What made you draw the lines here? Was it just Judd's proximity to your life through being born in the same town? Or something else?

BERRY: Perhaps one way to answer this is that there’s not a lot of pop culture that’s directly connected to Excelsior Springs, MO! You’re right that I do often think through “lowbrow” artforms, but nothing really fit in with this book. After turning in the final draft of the book, I began to write about country music. My hometown has come up quite a bit in that writing...so I guess I’m not done with it. But the lens that I’m taking in recent writing still feels different from the Hall of Waters project to me. Judd was where my ekphrastic essaying stopped with this book because Judd represented so, so much. I began thinking about Judd because we share a hometown, yes, but I couldn’t stop thinking about him. That he essentially fled our hometown but ended up reifying many of the cultural values that he was presumably running away from was fascinating to me. I kept wanting to talk to him, but he’s dead, so I couldn’t. Hence the many pieces that address Judd directly. It’s a one-sided conversation, yeah, but framing my inquiry through a sort of epistolary helped me think more critically about him. I wrote more Judd pieces than I ended up including in the book because he gave me SO much to work with.

ALEX: Are any of the other Judd pieces forthcoming anywhere? I’d love to read more of them.

BERRY: There aren’t at this time. Honestly? It didn’t even occur to me to send those pieces out for publication. I’m very much an overwriter, especially in the earlygoings of a project, and I’ve gotten used to having a lot of material that I don’t ultimately send anywhere. Maybe though I should set up a Patreon and post those Judd essays as outtakes/B-Sides!

ALEX: Other pieces in the book are addressed to your wife. But, conspicuously, you never address any of the pieces to your mom, whose loss and love resonate through the book. Why did you make the choice to mainly address Judd and your partner, but no one else?

BERRY: I love this question, because this isn’t something I actively thought about before! For the same reason that addressing Judd helped me better reach those essays, I think addressing my mom in a similar way would have opened up way too much for this book to handle. My mom passed away about half a year before I started this book, so her death certainly brought some shading over everything. But I’m a writer who tends to put a lot of distance between experiencing something and writing about it in a concerted way. I feel like Hall of Waters is not my mom book. I feel like it’s my dad book! I began writing about my mom more purposefully and completely this past summer (my folder of drafts is titled “MOM STUFF”), and I’m accessing thoughts and themes that I think would have been distractions in Hall of Waters, would have taken away from the thematic clarity that I hope Hall of Waters has.

ALEX: So can we expect a forthcoming mom book, then? Alternatively, what other things are you working on?

Berry: Oh yes, eventually, project codename hashtag MOM STUFF will be a manuscript! I started writing into it at the Ragdale residency in Illinois, and over that month I basically realized I was writing four different MOM STUFF chapbooks, that may just be able to comprise a book in four sections. One section is a sort of mixtape of music essays about songs my mom loved to listen to; largely country music, but not exclusively. “Sammy Kershaw’s “Queen of My Double-Wide Trailer” and Martina McBride’s “Independence Day” and Aerosmith’s “Dream On” and Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror” and Tina Turner’s “What’s Love Got To Do With It” and more. Another section is about turquoise--the color and the stone--as it was my mom’s favorite. Another section has been where I’ve been thinking through my mom’s attachment to gardening, and the various ways of she and I experiencing the spiritual. Finally, I’ve been thinking a lot about how I feel, personally, about the idea of being a mother. Specifically the breadth of experiences that can constitute a trans motherhood! Climate change has been a strong undercurrent of this writing too. So these related concepts are basically all I’ve been working on lately. Grief on the brain.

Alex DiFrancesco is a writer of fiction, creative nonfiction, and journalism who has published work in Tin House, The Washington Post, Pacific Standard, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Brevity and more. Their essay collection Psychopomps (Civil Coping Mechanisms Press) and their novel All City (Seven Stories Press), were published in 2019. They are the recipient of grants and fellowships from PEN America and Sundress Academy for the Arts. Their storytelling has been featured at The Fringe Festival, Life of the Law, The Queens Book Festival, and The Heart podcast. They can be found @DiFantastico on Twitter.