In Poet's Corner, Tucson Poet Laureate TC Tolbert shows us several drafts and revisions of a poet's work, then speaks to that poet about the writing process.

Poet's Corner with Kristen Nelson

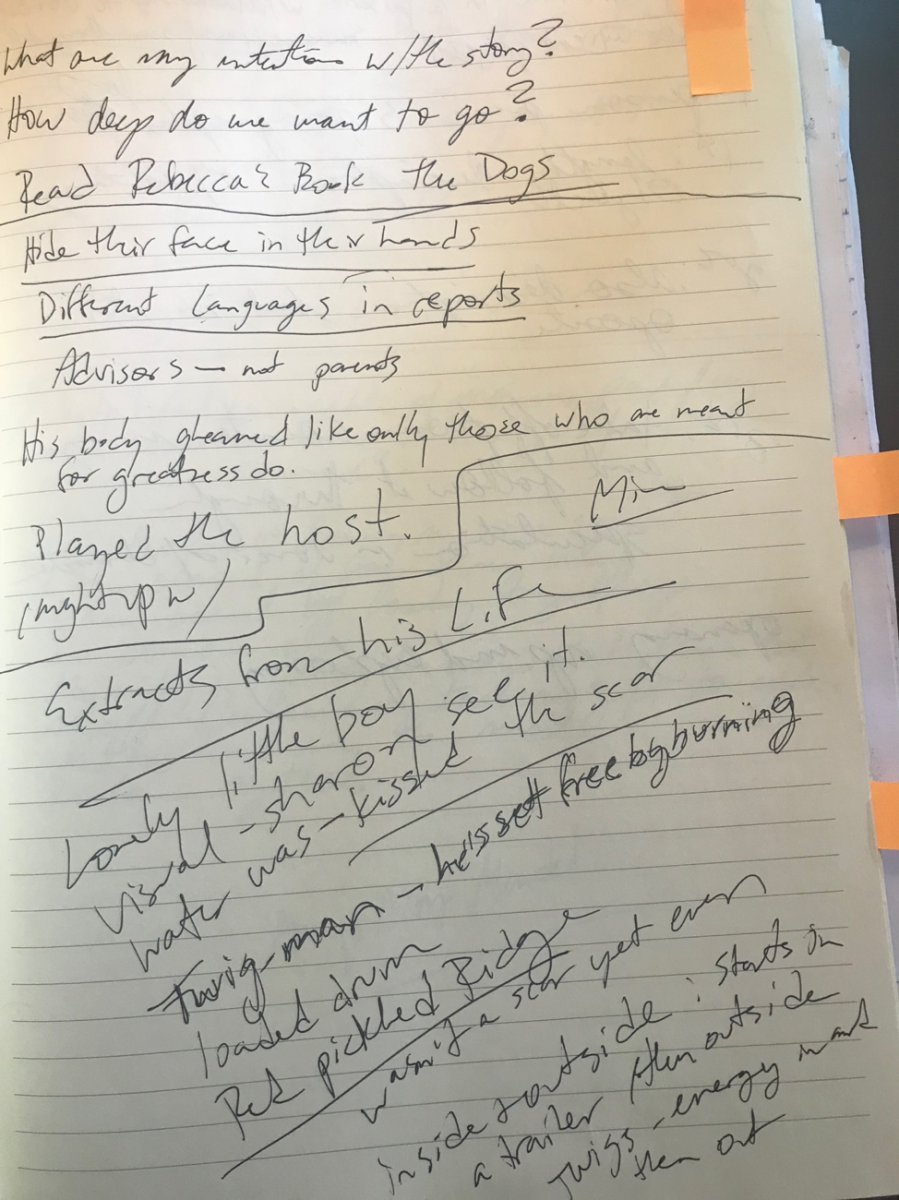

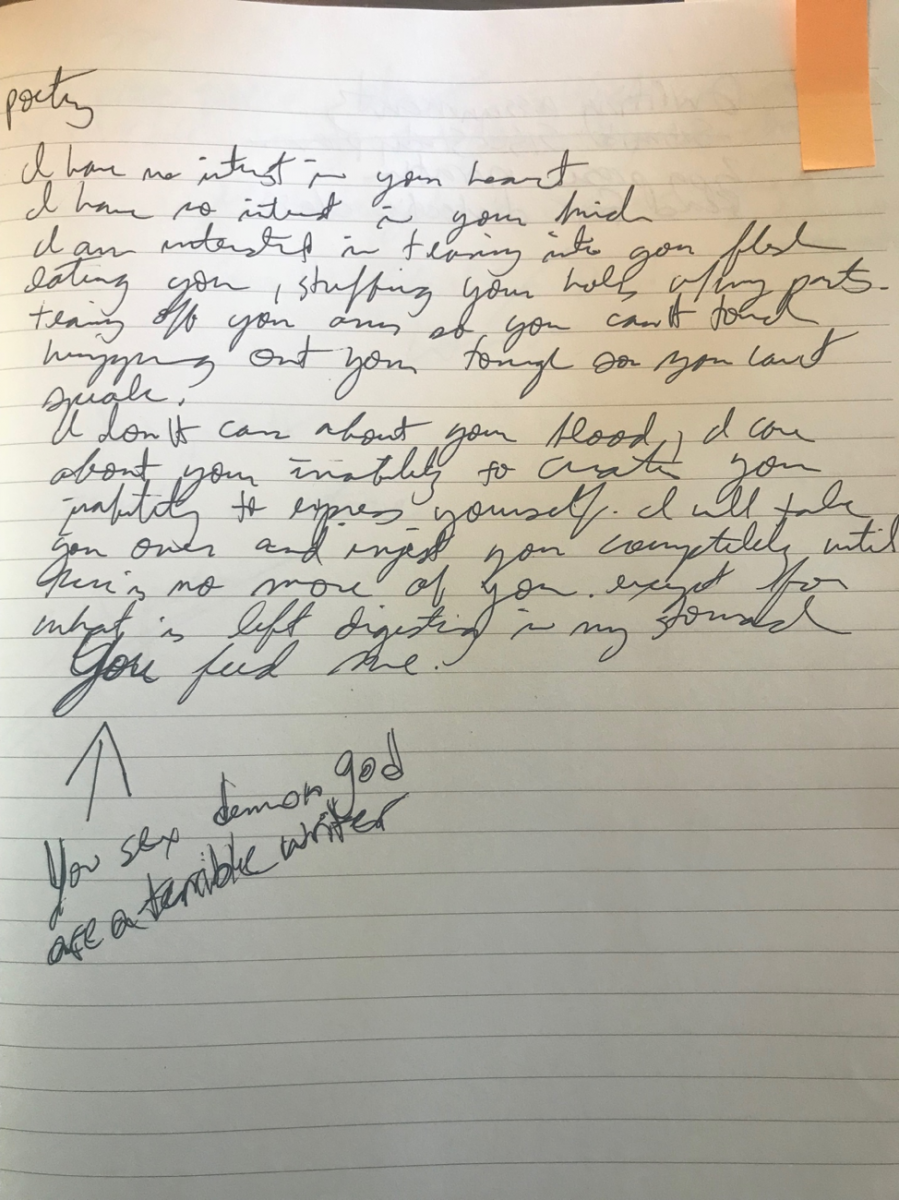

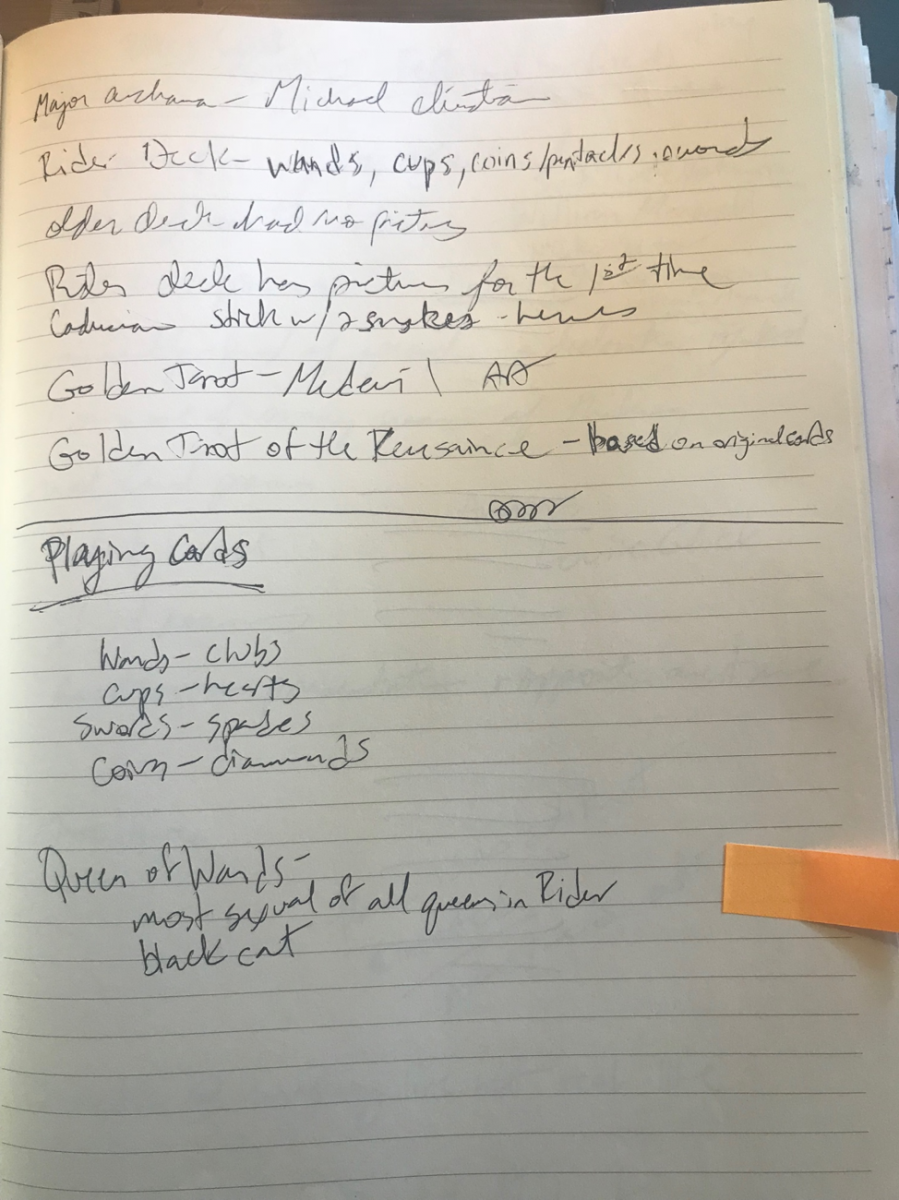

Draft 1

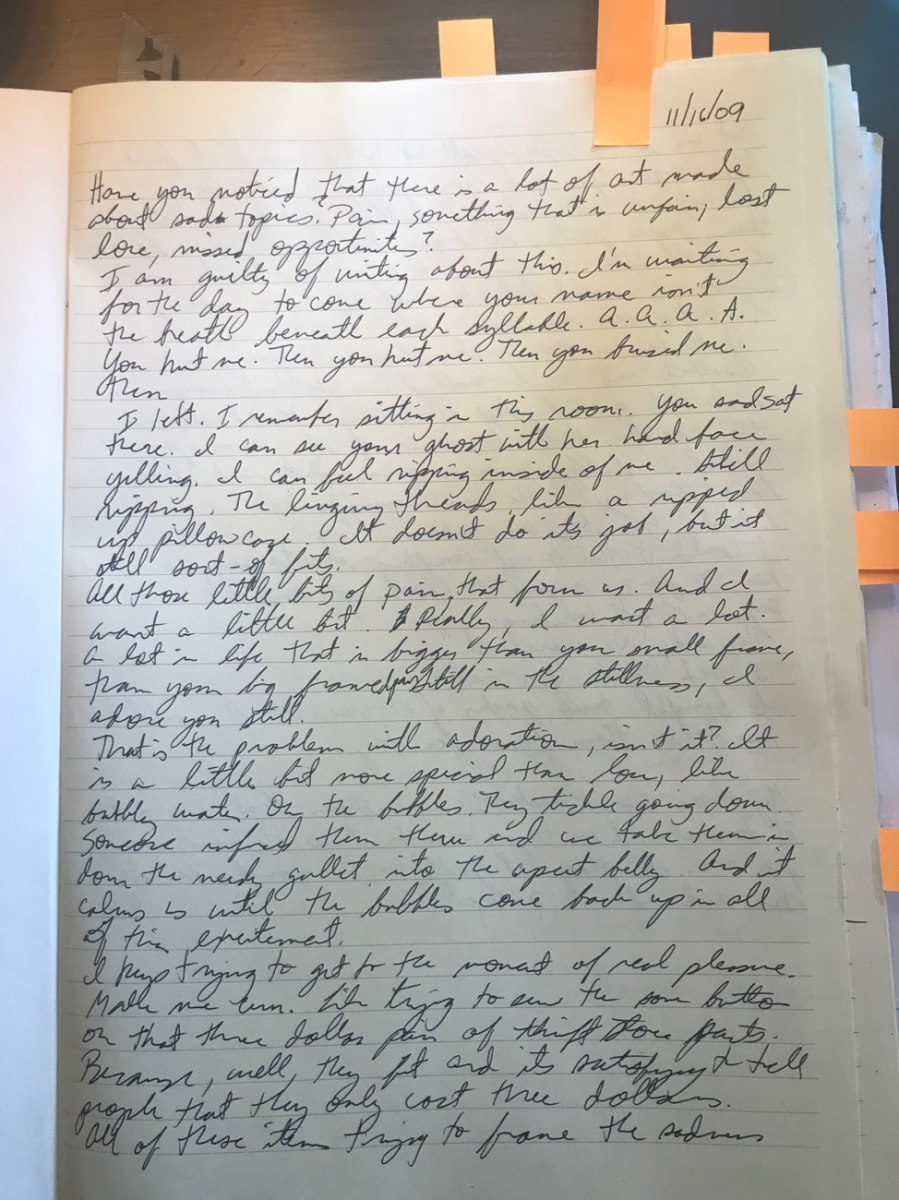

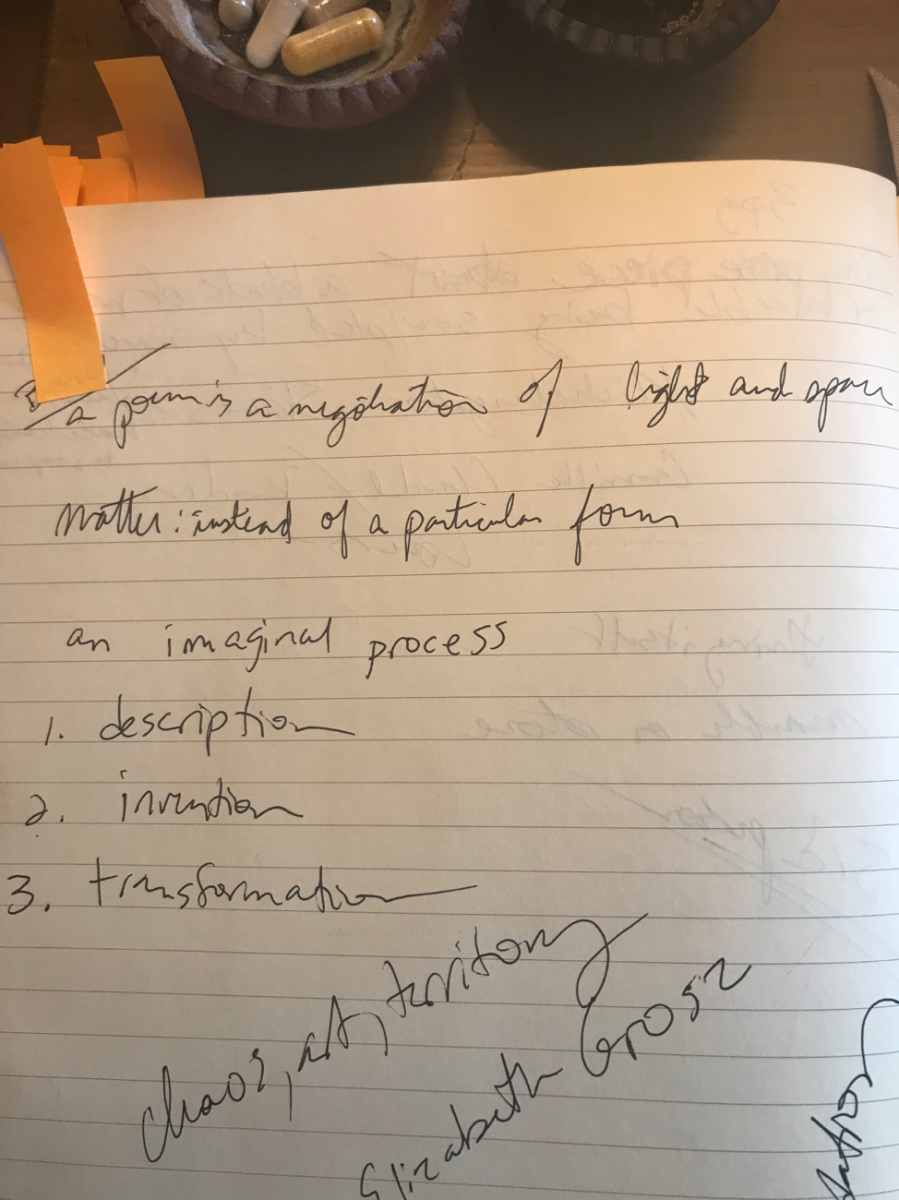

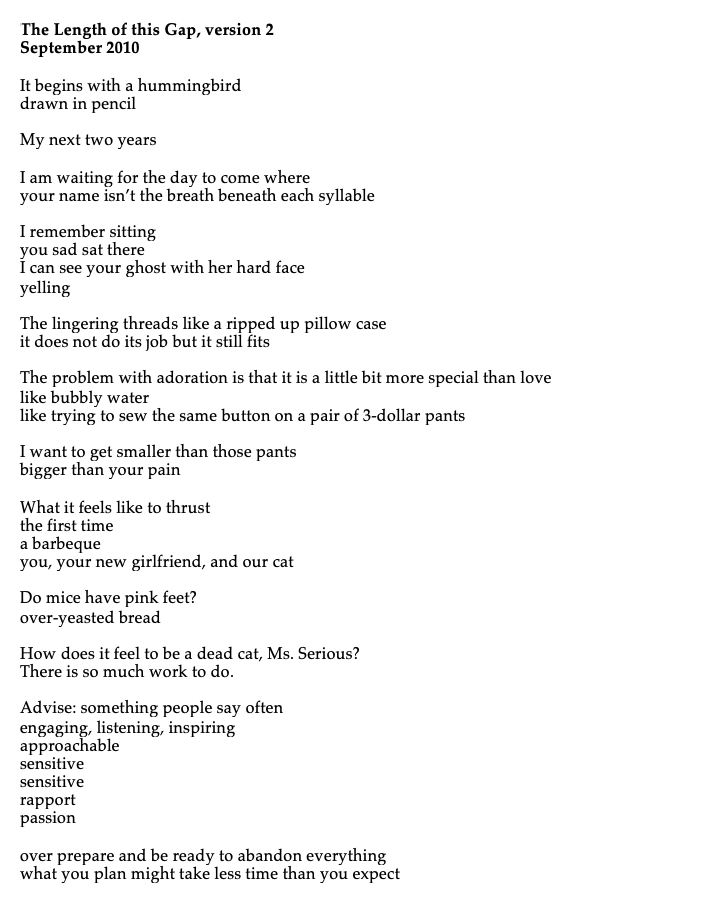

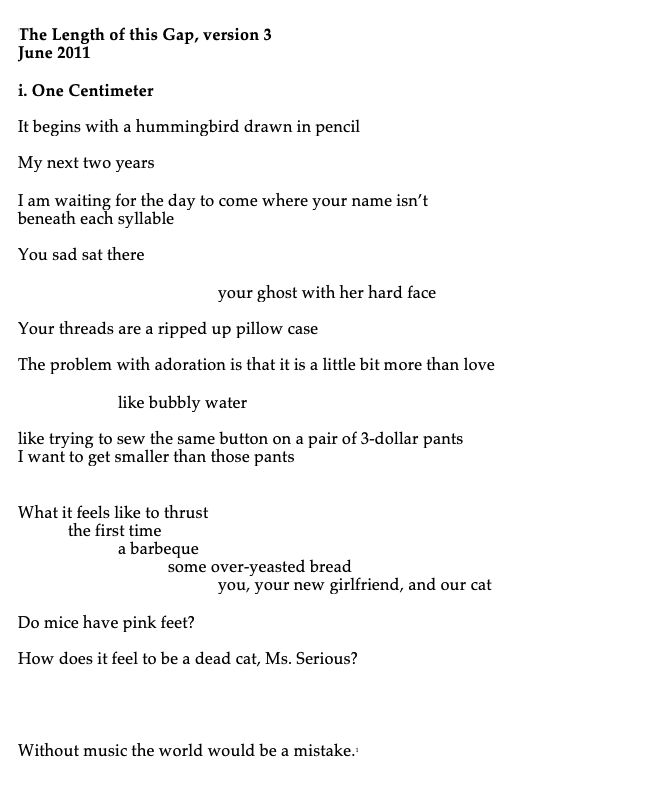

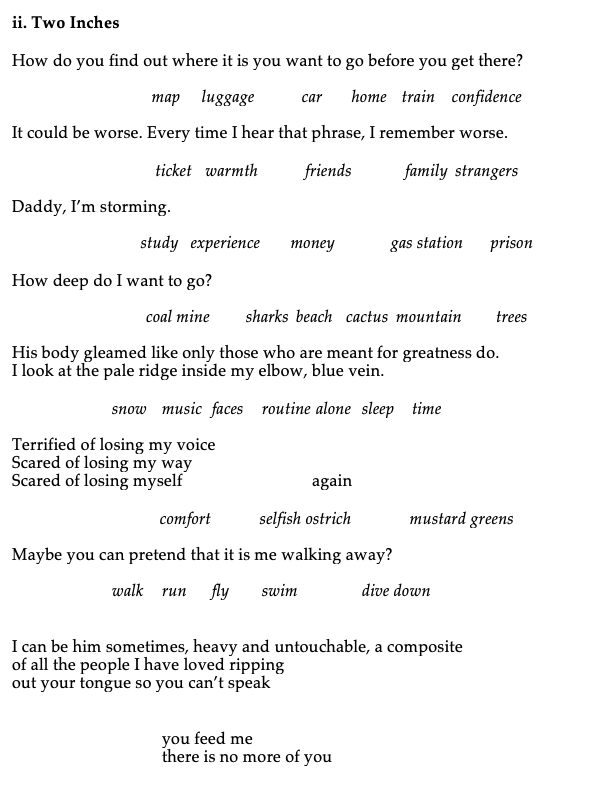

Draft 2

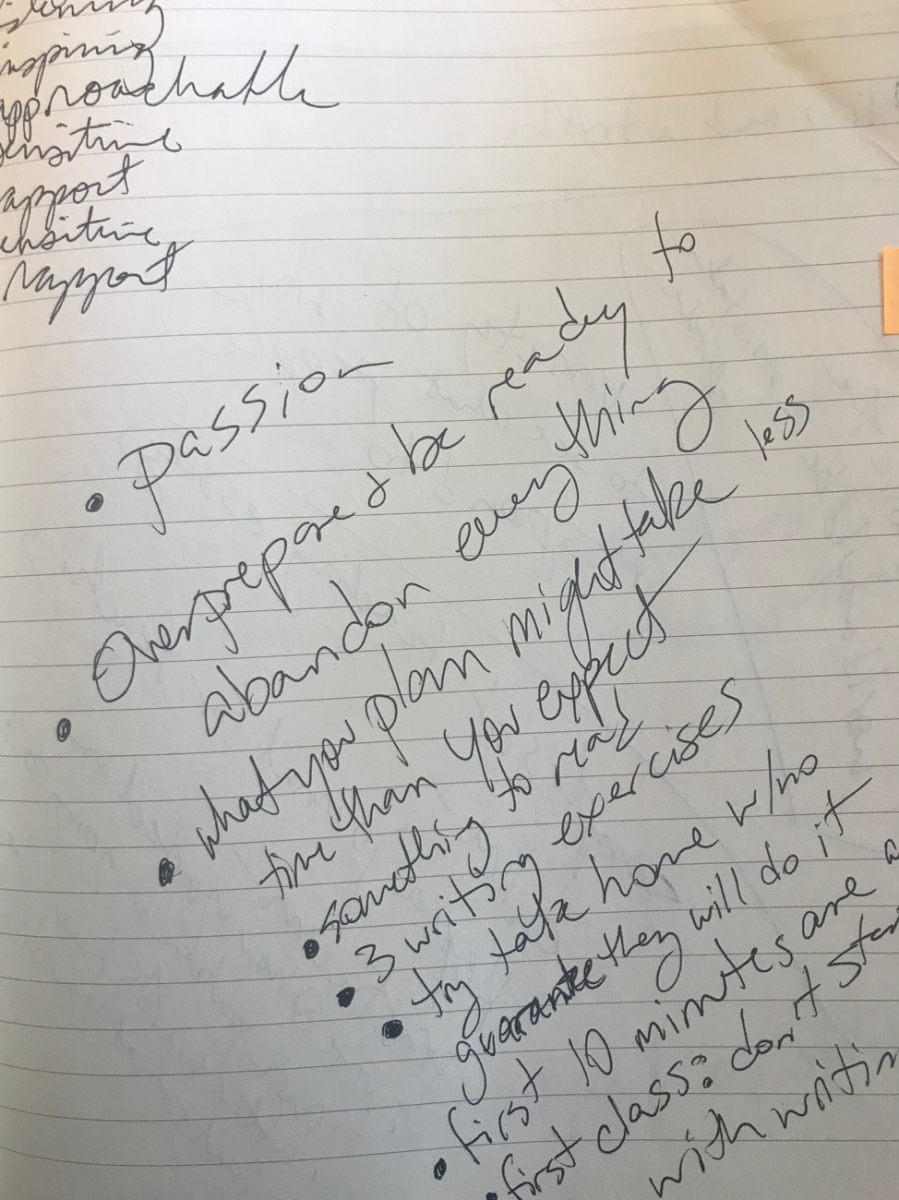

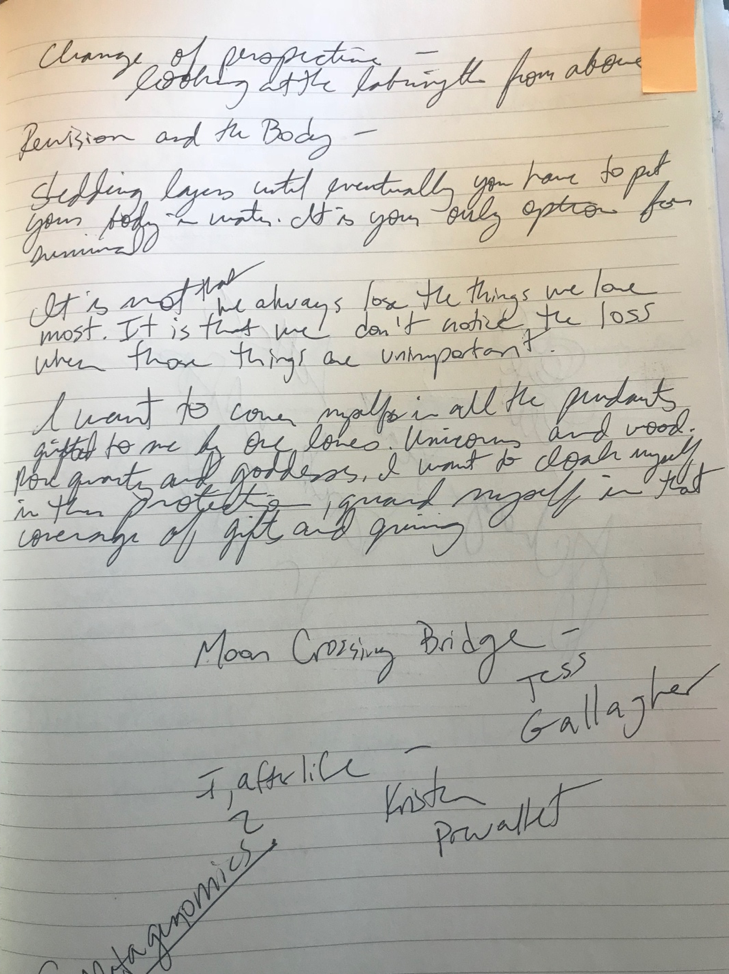

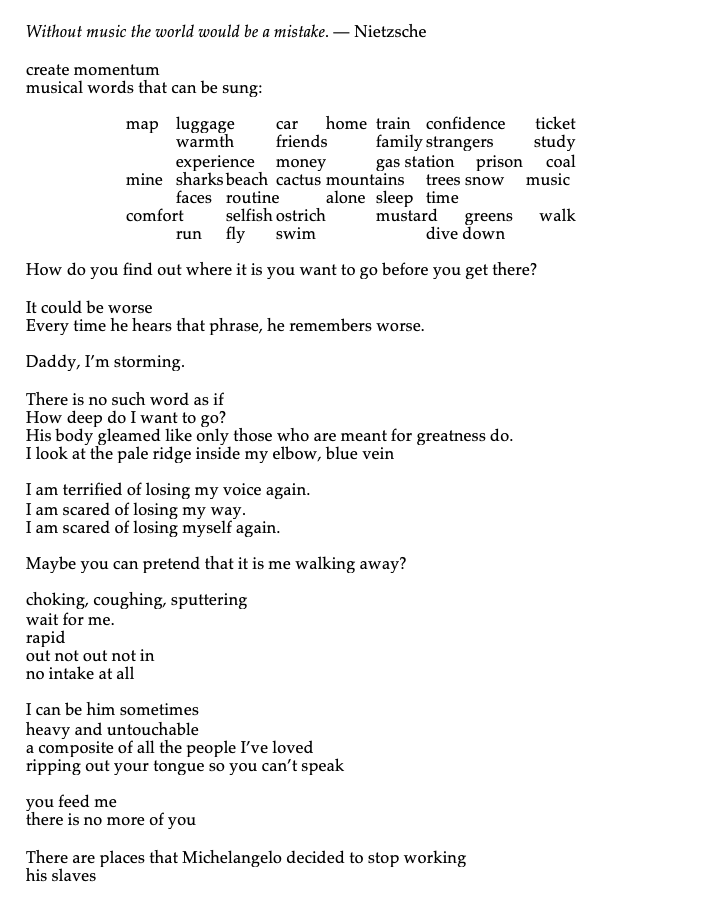

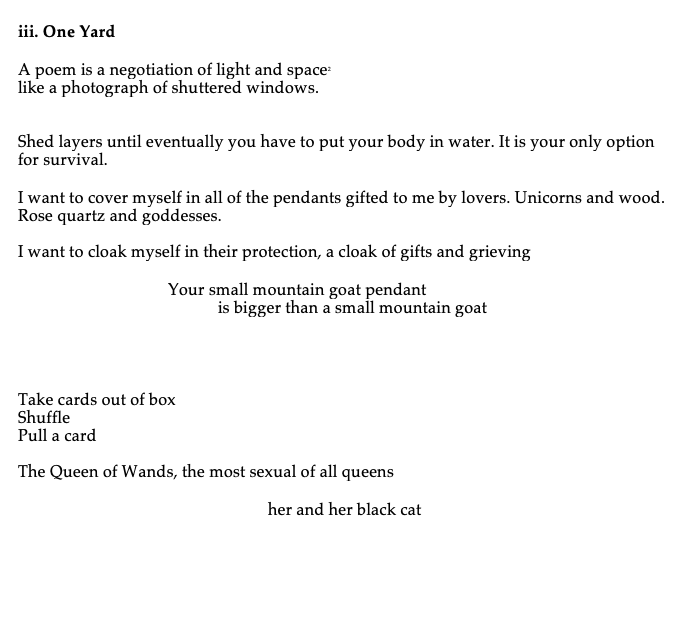

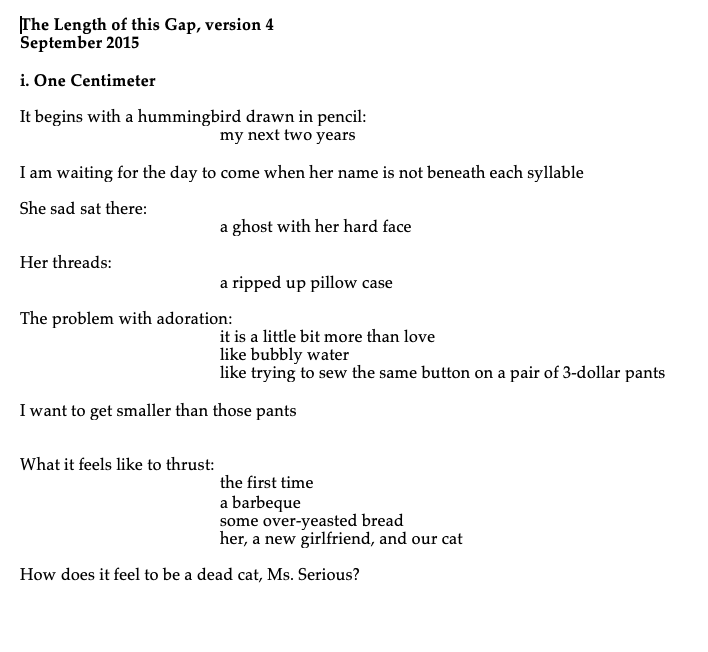

Draft 3

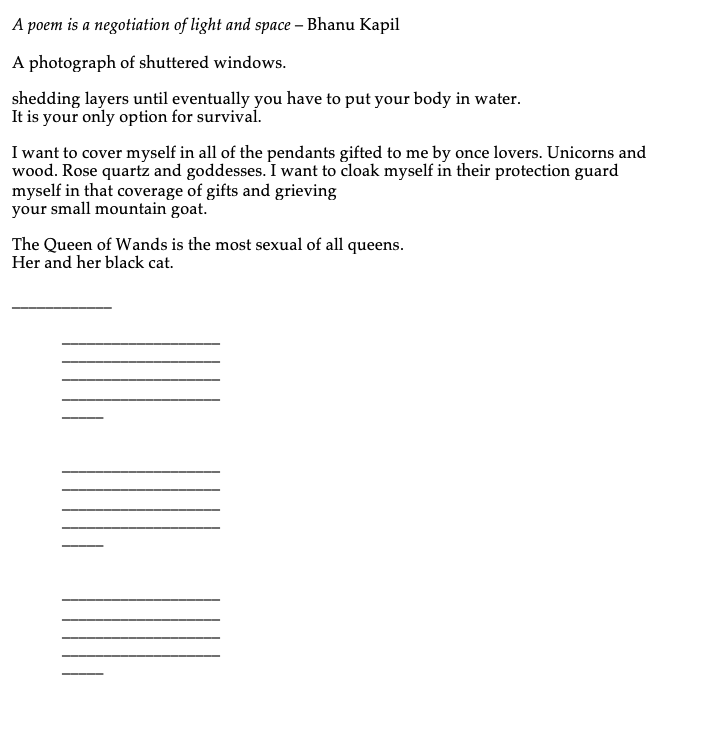

Final Draft

***

Questions and Answers for Poet’s Corner

TC Tolbert with Kristen Nelson

TC: The first thing that jumps out at me is that almost all of the words in the final draft are actually present in the very first handwritten pages but it took over 8 years for the poem to be realized. I’m utterly inspired by your patience and the seemingly surgical nature of culling that happens in these drafts. The process itself seems to echo a line from the poem that appears in each draft: “I want to get smaller than those pants.” What is the relationship between writing and compression (or constriction) for you? I’m struck by the expansiveness of time and the sharpening, winnowing of the language.

KN: I think about editing as a sifting or distillation process. Very rarely does a piece of writing come out complete or mostly done on the first draft. I want to say, “never,” but it happened to me once, so I’m saying “very rarely.” I believe that writing is part creativity, part dreaming, and part channeling. So, when we write, we are listening, sleeping, and generating all at the same time. It’s hard to get that exactly perfect on a first try. I try to give myself enough room in the first draft of something to sift through it later. I record everything that comes through. The shape, much of the form, and the moments of shimmer are distilled or sifted through in the editing process.

I keep picturing a handheld flour sifter that my grandmother used for baking. When you pressed in the metal lever on the handle, it would rake a wire across the mesh lining the bottom of the sifter and push through very finely sifted flour into the bowl beneath. It was a laborious process, especially when you were baking 500 Christmas cookies that day, but there was no discussing it. The additional labor was necessary. The sifted flour made the final product—the butter cookies covered with rainbow sprinkles—smoother and more consistent in texture. In these versions of these poems, I see the editing as a similar aeration process.

TC: Do you often begin by handwriting and intentionally over-writing? How does handwriting serve your writing process and do you ever return to handwriting once you’ve started drafting on the computer? How does your relationship to the poem change when you move the draft from handwriting onto a typed page?

KN: I almost always begin a piece by handwriting. I wonder if this is a generational thing. I started writing just about every day when I was about 9 or 10 years old. I’m 40 and 30 years ago we didn’t have access to portable pocket screens that we could type on. These tiny screens are awfully convenient, especially when your fingers have been trained to text messages on tiny keys. But, I always start with a notebook. I like that my brain moves faster than my hand when I’m writing with ink on a page. It distracts my internal editors. My hand is always trying to catch up, and that works well for me. It helps me to sleep, and create, and listen all at the same time. I don’t usually return to ink and paper after I transcribe the work onto a computer unless I’m starting over completely.

I don’t think about my process as over-writing, because I think there is an intentionality in over-writing that I just don’t have. When I get driven to the page to write something down it is usually a furious need to get it on paper, to capture, to grab it before it’s gone. An act of desperation. The intentionality is one in which I simply try to capture as much of it as possible before it is gone. I think my first drafts are extremely unrefined. Sometimes jumbled all in a single paragraph, sometimes with some haphazard line breaks. They’re sloppy. They’re hurried. They are also completely devoid of self-consciousness and unbridled. I don’t think they are poems yet. They are notes towards a poem.

TC: I know that Carole Maso is one of your writing heroes and there is this thing she writes in AVA: “So that form takes as many risks as content.” This made me think of the shift from version 3 to version 4 – where the colons come in and the list of “words that can be sung” gets cut. It seems to me this is the point where the poem is taking its big risks with form. Did this feel like a risk and will you talk to me about that shift and how you are thinking about form in this piece? When (or how) do you know a poem has found its form?

KN: Hands up to Carole Maso, everyone! This was a definite moment for me of killing my darlings. Because, who doesn’t love a list? Who doesn’t love action verbs and particular nouns? Who doesn’t want to keep all of that motion contained in a poem? Who doesn’t want a poem to sing? But, the poem wasn’t saying what I wanted it to say. The lists were cluttering up the page in a way that distracted from the true poem. The lists weren’t true or right. It is difficult for me to describe what are “true” and “right” when it comes to creative writing. We have so few rules. But, it is the true and right that rise up in your guts, the humming in your throat or your chest or your groin when you know that your poem is finished. For those of us who have bodies that bleed every month, I think it is very similar to the feeling of that first rush of blood. When you’ve been waiting for your blood to arrive, there is a moment that first bit of menstrual blood exits your vulva. You have a deep knowing that this time it is not anticipation. It can come with anxiety, with relief, with pain, with joy, with disappointment. But there is no denying it. The blood has arrived/the poem is done.

TC: On page 9 of your handwritten notes you write: Revision and the Body – Shedding layers until eventually you have to put your body in water. It’s your only option for survival. This reminds me of Adrienne Rich, who writes in “When We Dead Awaken: Writing As Re-Vision” (first published in 1972): “Re-vision – the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction – is for women more than a chapter in cultural history: it is an act of survival. Until we understand the assumptions in which we are drenched we cannot know ourselves. And this drive to self-knowledge, for women, is more than a search for identity: it is part of our refusal of the self-destructiveness of male-dominated society.” Does this quote of Rich’s resonate with you and if so, how? Also, here we are 45 years since this was published – in what ways might you push back on and/or add to her thinking about revision and survival?

KN: Who am I to push back against this bit of brilliance: Until we understand the assumptions in which we are drenched we cannot know ourselves? There are certain women who have come before me who I do not push back on; I just sit with their work and hope to absorb it into my body. Adrienne Rich is one of those women. My answer to this question is complex. It meanders. But stick with me, and I’ll get there.

I’ve been obsessed with Rich’s poem Diving into the Wreck since I was in high school. When I was 14 years old, I started SCUBA diving, and within the next year, I was sexually assaulted for the first time. I remember reading that poem a few years later and feeling stripped bare by a gentle aunt who wanted to peel off my trauma, baptize me in the ocean, see my scars, and love me. I could bring a knife and a book. A knife and a book to examine the wreck. In my freshman English Literature course, I fought with my teacher over that poem. I screamed at her in the middle of class telling her that her interpretation was WRONG. Rich’s poem was my poem, and damn-fuck-it no one was going to take it away from me or tell me what it was or wasn’t about. I think about that teacher, who let me fight with her, and now recognize the gift she gave me. At the end of class, she smiled at me.

In 1973 in the New York Times, this is what Margaret Atwood had to say about Adrienne Rich’s newly published 7th book of poems, Diving into the Wreck.

"If Adrienne Rich were not a good poet, it would be easy to classify her as just another vocal Women's Libber, substituting polemic for poetry, simplistic messages for complex meanings. But she is a good poet, and her book is not a manifesto, though it subsumes manifestoes; nor is it a proclamation, though it makes proclamations. It is instead a book of explorations, of travels. The wreck she is diving into, in the very strong title poem, is the wreck of obsolete myths, particularly myths about men and women…This quest—the quest for something beyond myths, for the truths about men and women, about the I and the You, the He and the She, or more generally (in the references to wars and persecutions of various kinds) about the powerless and the powerful — is presented throughout the book through a sharp, clear style and through metaphors which become their own myths."

When Rich won the National Book Award for this book in 1973, she accepted it with fellow-nominees Audre Lorde and Alice Walker on behalf of all women.

I feel like it is important to give this personal and historical content on Rich, because her poetry was not only shaped by the world that brought her up, she shaped that world with her poetry. How profound it must have been to craft her world with poems. So, now, I want to return to the quote you chose. We are now in an era where the president of our country was voted into office by 54% of white women and who condones grabbing women “by the pussy.” (I am a white woman and keep returning to this statistic with horror.) This is an era when sexual predators are given seats on the Supreme Court. Is it too simple for me to say, I think we should be reading more Adrienne Rich and Audre Lorde and Alice Walker? Perhaps they can help us re-vision our world. Perhaps they can give us the courage to write the poems that will shape our world and our future. Perhaps they can help us find clarity to move forward refusing self-destruction. Perhaps they can help up go down together into that black water again “to see the damage that was done/and the treasures that prevail.”

TC: I'm hoping for Poet's Corner to function as a teaching tool and companion for fellow writers. Could you share a suggestion for approaching revision? And/or: when you don't know where to go next with a poem but you know the poem is not yet finished with you (or you are not yet finished with it), what do you do?

KN: I keep trying new things with it. I shared 5 versions of this poem with you, but there were many more versions. I don’t know how many versions, but ten years of versions. Sometimes I write quickly, but I don’t edit quickly. If a poem isn’t finished, I don’t try to rush it to completion. Sometimes, I’ll walk away from a poem for a year and return to it with new eyes. Sometimes, I’ll print a poem out and write all over the printed page crossing out words or lines to see what it looks like without those bits. Sometimes, I’ll give it to a friend whose work I admire to ask for help. What do they see that I don’t see? Sometimes, I’ll open a new document on my computer and copy and paste lines into the new document from the old trying out an entirely different form. What happens when you give the lines a lot of space in between? What happens when you push all the words together into a column? Keep going until the blood comes.

TC: Finally, the book in which this poem appears (and with the same title – the length of this gap) was just recently published (you can buy it here!) – congratulations! How are you seeing the poems differently (or are you) now that they exist in book form?

KN: I don’t think I do see the individual poems differently now that they exist in book form, but I am sitting in a space of deep gratitude that the book exists in the world. It is a beautiful book thanks to the photographs of my altar that Julius Schlosburg took for the cover and thanks to the labor of the publisher. I’m extremely grateful that these poems, that are sometime gruesome and hard to read, wound up in such a beautiful object. It’s not easy to get a book published. (Hark! An understatement!) It can take a long time and many rejections before a book finds its home. I am very grateful to Caseyrenée Lopez of Damaged Goods Press, who found it in their stack of submissions and saw something in it. They were willing to put their labor into launching the book into the world. I know that this happens every day, but when it happened to me, it felt like a profoundly healing experience. A stranger in the world read my manuscript and believed it in enough to turn it into a book. I can ride on that simple, beautiful truth for the next ten years.

Kristen E. Nelson is a queer writer and performer, literary activist, LGBTQ+ activist, and community builder. She is the author of the length of this gap (Damaged Goods, August 2018) and two chapbooks: sometimes I gets lost and is grateful for noises in the dark (Dancing Girl, 2017) and Write, Dad (Unthinkable Creatures, 2012). Kristen’s poem “After the Crotalus atrox” was anthologized in The Sonoran Desert: A Literary Field Guide and nominated for a 2016 Pushcart Prize by University of Arizona Press. She has published work in Bombay Gin, Denver Quarterly, Drunken Boat, Tarpaulin Sky Journal, Trickhouse, and Everyday Genius, among others. www.kristenenelson.com

TC Tolbert often identifies as a trans and genderqueer feminist, collaborator, dancer, and poet but really s/he’s just a human in love with humans doing human things. S/he is Tucson’s Poet Laureate and author of Gephyromania (Ahsahta Press 2014), 4 chapbooks, and co-editor of Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics (Nightboat Books 2013). www.tctolbert.com