Content Warning: This essay includes references to childhood abuse; more specifically, parent-child violence.

I remember the moment I realized, seriously, that I wanted to be a writer. It wasn’t the first time I wrote something for an audience, although that did something to me, too. That was a different kind of moment, one that was tinged with external validation, something I lacked in my young life (I was in third grade, and I’d received an award for a Mother’s Day poem I wrote in order to make my mother—who was elusive and sparkly, suddenly appearing and vanishing just that quickly like a rainbow on a day of showers in the Spring—happy enough so that she would stay). But the moment I realized I wanted to pursue writing as a lifelong practice—perhaps, I thought, like someone pursues a religious faith—happened when I was a sophomore in high school, and it happened because of an English assignment.

To say this now seems like such a cliché, but it’s true. I am the writer I am today because of the teachers who made me believe that to follow this frustrating, aching, necessary, glorious, painful, dissatisfying, and endlessly life-affirming work was something I had a kind of propensity for. And that is because I explicitly did not have the kind of parents or guardians or other figures in my life from whom I could have believed in myself to do just about anything. It’s probably worth noting here that I didn’t think much of this teacher. To be honest, I didn’t even like her. But she gave me an assignment that changed my life—and not only because it encouraged me to follow writing, but also because the assignment itself provided me with a life-saving coping mechanism. At the time, I could feel something incredibly healing happening to me, although I wouldn’t understand exactly what, or how, until much later: until after I began therapy, until I started to carve out a consciousness for how trauma impacts the brain and the body, how processing one’s feelings and experiences regarding pain can be a kind of regenerative practice for surviving and remaking the self that has had to navigate immense damage as one develops into an adult.

We’d just finished reading Oedipus Rex, and I remember being quite taken with it. The teacher asked us to write a poem about the symbolism of Oedipus, but her one stipulation was that it couldn’t rhyme. I had no idea poems existed that didn’t rhyme. I recall scoffing about it to my mother on the phone (I’m not sure what city she was in, or whether she was at her apartment where I lived but did not often live with her at the time).

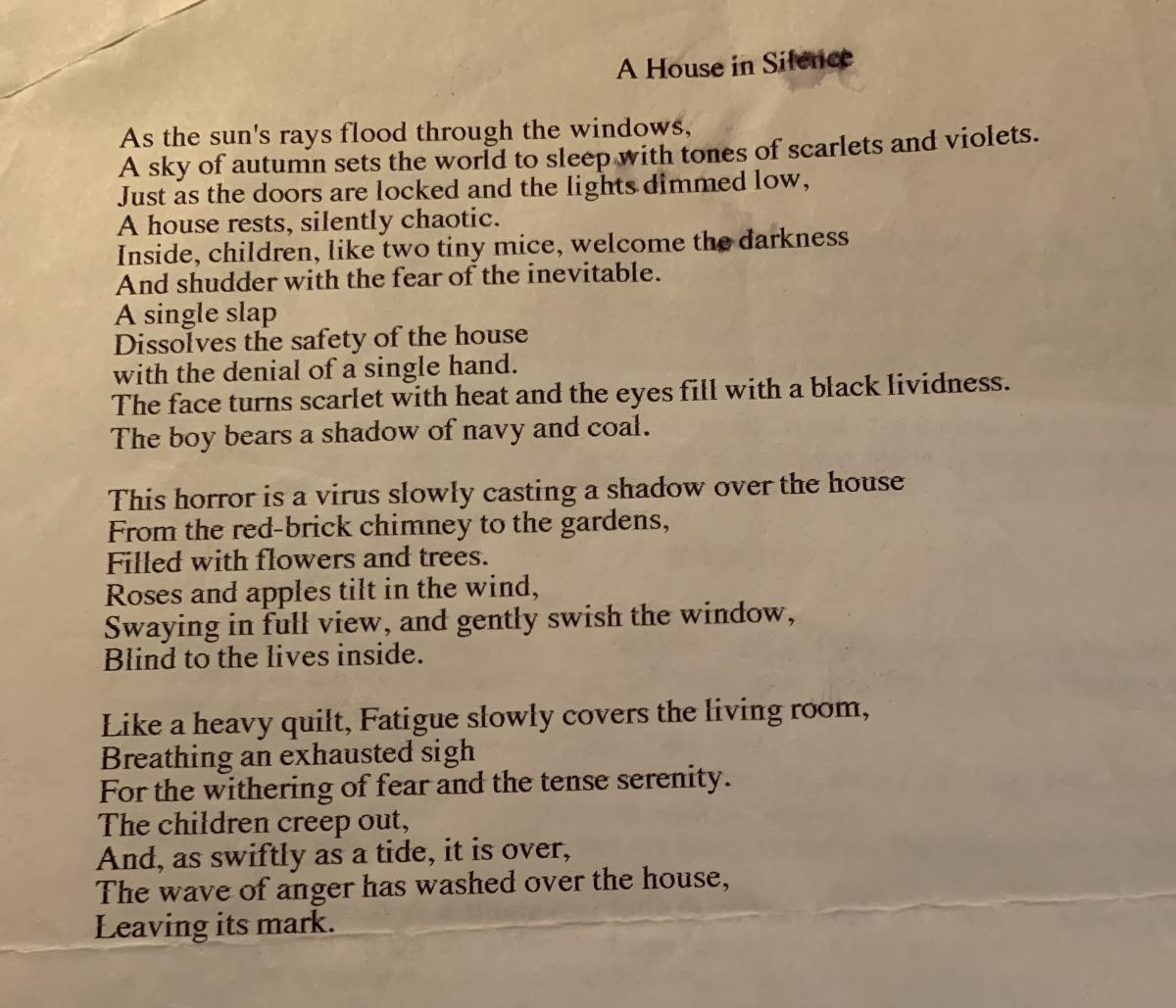

At the same time, I was trying to navigate experiences laced with childhood abuse that were becoming increasingly untenable—some of these experiences directly happened to me, but those that were almost more difficult were the ones impacting my twin sister and my older brother, and that I was forced to witness while remaining silent, and feeling that silence was a matter of my survival. It was an impossible double-bind to watch my brother and sister be abused, and feel there was nothing I could do to stop it. Even though I, too, was the victim of abuse, much of my teenage years were framed and defined by what I couldn’t prevent from happening to my siblings. I had fantasies as the abuse was happening where I would scream at my dominant, protective, reliable, hyper-alarmist, loving, narcissistic, terrifying father to stop what he was doing and point to my brother’s face, splotchy red from crying and fear. But just like he held my brother’s face while threatening him for doing poorly in school, or for the number of other illogical reasons that he would claim provoked his rage, that time, this time, the other time, the many, many times, my father also would hold the mouths of my words in my own throat, snuffed into silence, relegated to a fantasy that I never felt courageous enough to act on. Even witnessing my brother in terror and pain destroyed me inside.

I decided I would use this Oedipus assignment to write about what I had experienced, what I struggled to witness. It was a revelation to me--therapy before I would find (and be able to afford) therapy--and set me on a journey towards healing the wounds that could have otherwise stopped me dead in my tracks in more ways than one. I’m not even sure I could explain what it did to channel all that I couldn’t say in a poem. I’m sure I was terrified, at least a little, to share it with my fellow students and my teacher, but the writing of it had been, suddenly, such a profound and powerful experience that my desire to share it with others, to have them witness and acknowledge my pain and my expression, became greater than my fear at having my deepest secrets exposed.

The teacher took me aside on the day she passed them back, and suggested that I submit it to the contest for the literary journal on campus. I didn’t win, or even get asked to publish it. But I’d remember that I had confided to her, in my own way, of my darkest secrets, and she had not rejected me. Not only that, but she had validated me, and validated the art that I was making out of my life. There would be other mentors, other teachers down the line who would do something similar for me, but she was the first one to show me that I could use the poem as the vessel for trying to understand the chaos that was my life then. It is a practice I have never forgotten, and it will always be the most important aspect of what writing is to me—more important than fame or publication.

Addie Tsai is a queer, nonbinary artist who teaches courses in literature, creative writing, dance, and humanities at Houston Community College. She collaborated with Dominic Walsh Dance Theater on Victor Frankenstein and Camille Claudel, among others. Addie holds an MFA from Warren Wilson College and a PhD in Dance from Texas Woman’s University. Her writing has been published in Banango Street, The Offing, The Collagist, The Feminist Wire, Nat. Brut., Foglifter, and elsewhere. She is the Nonfiction Editor at The Grief Diaries, Senior Associate Editor in Poetry at The Flexible Persona, and Associate Fiction Editor at Anomaly. Addie is the author of the queer Asian young adult novel, Dear Twin.