“How do I prove that I exist and that I have existed?”

One in three Chinese Americans are using a false last name. I am one of them.

When my biological father took a dead boy’s name as his own, after being orphaned in World War II, my father—an undocumented child-refugee of unknown descent—became Chinese. After being placed on an adoption boat for Hong Kong, where he was adopted by a Hakka ship captain and his second wife, my father grew up in the shipyards. Years later, to avoid falling into street life, my father was sponsored by his foster sister, a Hong Kong immigrant turned American doctor.

I don’t think I look like the undocumented Chinese immigrants who arrived in San Francisco in the first half of the twentieth century. Paper daughters are supposed to take the name of their sponsoring father. Yet I feel connected with my father’s fake Chinese lineage, and by default, mine. Like undocumented, Chinese paper children, I have papers that feel deceptive—I became a child of foster care. Growing up in the system meant I was a “case,” itemized and shuffled through the courts, shelters, group homes, and institutions meant to disappear, and even criminalize, my survival. Once my paperwork disappeared, once I grew up, I had to learn how to find and reconstruct my own records and stories.

How do system-impacted children grow up, and begin to record their lives?

This is a question I’ve asked myself three times, for each year when I co-coordinated an Academic Writing in the Borderlands teaching and workshop series. This series of workshops centered around U.S.-Mexico Borderlands and their impact on either side, including the in-betweens of migration. Both writing and general education instructors dove into workshop exercises designed to strengthen their learning, teaching, and support for students in light of the political and personal nature of these borders, and in particular, how they impact our Tucson community.

The collaborative and mentorship aspects of Academic Writing in the Borderlands extended to its leaders, too: the University of Arizona Writing Programs (Nataly Reed and myself) and Writing Skills Improvement Program (Andrea Hernandez Holm) cultivated professional development within our programs to pay it forward to our instructors and students, who could seek the Writing Skills Improvement Program for their tutoring services and their own Borderlands undergraduate workshop series. In June 2025, the Writing Skills Improvement Program announced its closure on Oct. 13, 2025. Academic Writing in the Borderlands’s current hiatus reminds me of the fleeting nature of getting too close to spaces that allow for documentary work: at minimum, it requires funding. More importantly, it requires being able to ask and to pursue my lifelong question: “How do I prove that I exist and that I have existed?”

what I wanted as a former foster youth:

the American Dream of a new, freer life.

[...] Of having the documents to prove it.

May 2013. Photograph by Carol Highsmith. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

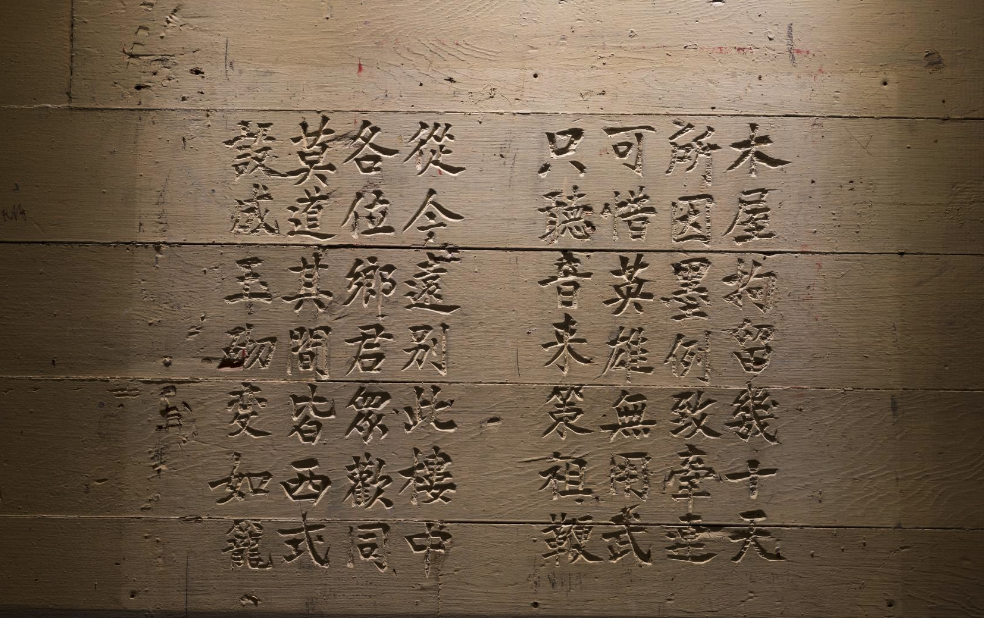

One way, in showing up to lead and to listen, was, in capturing the sounds that I gravitated to. My father used to recite his paper name in Cantonese, partly because had to learn the language, then when he immigrated to San Francisco, my father practiced reading and writing his English name. Charting a written name, reciting it, and committing its histories to memory was an act of defiance. How deeply could my father commit to a dead boy’s imagined life? The more my father pawned and performed the sounds that made him Chinese, the more he found a story for profit. My father was somebody, not undocumented.

In the Academic Writing in the Borderlands workshops, I scribbled questions on our discussions on positionality, witness, documentary poetics, land conservation, migrant and refugee voices. I sketched maps of what my peers and colleagues shared, which often included histories of their homes and places of origin. As the workshops—and the years—progressed, I found myself flashing back to what I wanted as a former foster youth: the American Dream of a new, freer life. Of going home, any home, safely. Of being a daughter who wasn’t my father’s daughter. Of having the documents to prove it.

Listen to Brandom Som

Pulitzer Prize winner Brandon Som captures his histories and time transitions in Tripas, often riffing off “r” sounds—which don’t exist in Taishanese, his paternal grandmother’s language. In his opening poem “Teléfono Roto,” Som evokes the grief of La Llorona, a codeswitching in all her retellings, lessons, and communications. He writes the eponymous What-If: “If we remove their cases, the verbs creer & to create share / similar wiring.” There are more misheard and codeswitched listenings in “Fuchi,” where Spanish and Chinese sounds circle around the levity, violence, and suspense of moving from language to language, until it centers on his grandmother, who worked on circuits at Motorola. A literal broken telephone.

The telephone becomes an “Inventory,” a litany of “-ah” translations for the missing English “r.” Whether the English “r” can be replicated in Som’s elders’ language or whether capturing the uncapturable is an obsession that sings long after the last caller has hung up, the precise unknowns are an unearthing and an erasure. My first language is Taishanese, learned from my mother whom I don’t know, other than having memorized her native tongue. It’s probably unsurprising that I’ve gotten critiques on my “r” sounds and enunciations, a silence I was taught. A trembling, as if I’d swallowed the sounds of what makes me an American citizen.

I’ve spent thirteen years teaching my students to write & to protect

the regular practices of documenting their stories.

Long after I left my parents’ home, time and time again, I remember that the “-ah” professes a loved one’s proximity to the receiver: they know us more than we know ourselves. They “-ah” whispers admonitions, expels frustrations, “& [sings] of separateness.” Ultimately, the “-ah” is a love language. “Though not on a map / its lilt [echoes] the geographies,” even while cooking in a family restaurant. The “-ah” is every day, and it doesn’t matter that there is no English equivalent in the same sound. This is perhaps one of the most uncomfortable truths in unearthing the unwritten. A paper name was forced to listen, to come up with rich, detailed histories of their families, ancestries, and villages. The only insurance to survive immigration interrogations and deportation was to know their sounds. Paper names couldn’t write down their stories. In reading Som’s poems, I realized that withholding his stories—and memorizing another child’s—saved my father’s life. And thus, my own.

It’s ironic that I’ve spent thirteen years teaching my students to write and to protect the regular practices of documenting their stories. When I think about my father’s journey from his homeland to Hong Kong, I try to fade myself out to the Hong Kong that was his coming-of-age. What did he do, think, feel, say? I sketch places he must have encountered, such as his orphanage and adoption agency, which overlooks Lantau Island, and the route he walked with his foster sister to school. I draw real and imaginary locations, like my paternal grandparents’ home, where they were murdered. I documented how my grandparents died in my book We Remain Traditional, but even that was for me, not really my father. What couldn’t I capture? What was his journey, his transportations and time travels, through leaving his parents and trying to excavate a new life?

In the absence of a real name,

sounding out my family history—and sounding out myself—

is tentative, uncertain, and unknown. If I don’t do it, I disappear.

When I write, I map out the sounds, places, topography, times, and character journeys. In the absence of a real name, sounding out my family history—and sounding out myself—is tentative, uncertain, and unknown. If I don’t do it, I disappear. Som, a descendent of a paper son, listens. Som and I live in the same world in “Antenna” where “U.S. troops install // the miles of border razor wire, so-called concertina // for the coil that extends & flattens like the bellows / of a squeeze box.” This is the world where our proximity to bearing witness can be a choice: what is our witness to spending more time in getting to know someone? What is our witness to observing, listening, and practicing empathy? What is our witness to rebuilding trust or other forms of positive change? What is our witness to doing uncomfortable things, such as speaking and acting on behalf of uncomfortable truths?

Towards the end of the his poem, Som writes, “Listen to everything all the time.” Here he intones Pauline Oliveros, the American composer known for listening as homage to individual and collaborative efforts. “Antenna” ends with “in practicing . . . I [experience] listening with the palms of my hand.” The keeping of documents, the witness of telling the truth, the making of poems and stories and art—all of these are transfers to the physical world we inhabit, transfers made possible by the palms of our hands.

Som writes, “Listen to everything all the time.”

“Listen to everything all the time.” For students, it’s opening ourselves to our fears and doubts, which exist in the same world as our strengths and prides. For educators, it’s getting closer to the stories our students want to tell and to write. For the children who want to record and to document, without access to paper trails and proofs of existence, it’s writing our names, however we want them to be recorded. Only after taking on the lineage of our papers, whether they still need to or can be found, can we participate in acts of storytelling and community and share, in ways where we may be the only and first ones, but we won’t be the last.

In practicing my disciplined and diligent witness to the sounds around me, I hope to leap back in time, however long it takes, to document my histories. In listening, I may resurrect what has once been erased.

____________

Sylvia Chan is an amputee-cyborg writer, educator, activist, and author of We Remain Traditional (Center for Literary Publishing 2018). Her poetry and essays appear in Poetry Foundation, Zócalo Public Square, The Cincinnati Review, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading, among others, and have been named National Poetry Series finalist and Best American Essays Notable. Chan has received fellowships and support from the Poetry Foundation and Crescendo Literary Poetry Incubator, Zoeglossia, and The Center for Art and Advocacy’s Right of Return. Chan is based in Tucson, Arizona, where she teaches and works with crossover and foster youth.

____________

Downloadable lesson plan:

Time, Flashback, and Trauma Loops

In this lesson plan developed by Sylvia Chan, students have the opportunity to analyze a poem that braids a flashback(s) and explore the flashback world and “present” time of the poem by writing a poem that switches between past and present.