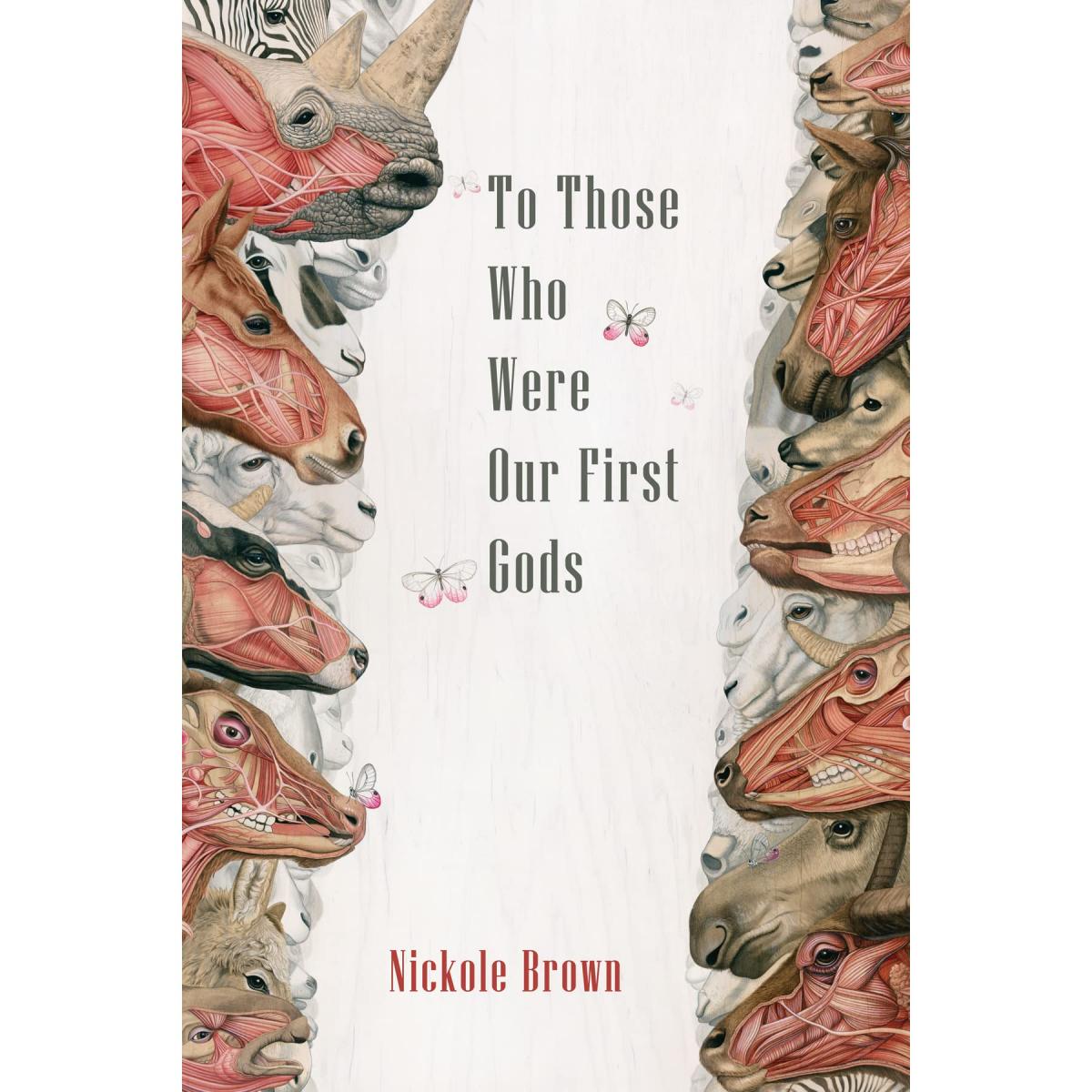

In the introduction to The Ecopoetry Anthology edited by Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street, poet Robert Hass describes the origin of the phrase “ecology.” Developed early in the twentieth century, the word “ecology” was coined from the Greek word oikos, which means “household,” signifying interaction among multiple creatures and their surroundings. Ecology then is a study of the environment as a whole: a complex, dynamic web involving all living things, including humans. Nickole Brown fully embodies such an ecology in her poetry chapbook To Those Who Were Our First Gods. The poems collected here claim Florida as an ecological landscape in the widest sense: parking lots, dumpsters, painted poodle toe-nails are as much a part of the environment as barred owls and wild panthers. This collection is aware of are aware of this land and its ecology, drawing our attention to the ways humans and nature interact.

To Those Who Were Our First Gods magnifies the small moments where two seemingly disparate worlds—the natural and the human—come together. In “No Ark,” a poem written for Mary Oliver, our speaker watches “a street robin bopping its dingy breast among the crush / of lipsticked filters and coke cans.” This poem begins mid-collision: there “ain’t no foxes here,” just “mewling strays tucked under the dangerous warmth / of a pickup’s hood.” Speaking directly to Mary Oliver, known for writing poems about the environment as untainted by human contact, “No Ark” feels almost contentious in its address. The poem takes a stand, positing the “chain store sprawl” as a place worthy of poetry; a place in which communing with nature is not only possible but equally important.

Brown elevates the culture of this specific place just as she does the landscape. “[W]e believe in wives’ tales around here,” she writes, quoting mama who fears a bird pecking at a window as an omen of death. Through the introduction of this folktale, Brown transitions to the most stunning image of “No Ark”: a luna moth, faltering against the asphalt of a parking lot. This moth was “big, big / as a burger, super-sized as a side of fries.” Through the folk tale, through the moth, Brown crosses the divide human and natural realms, bringing it all together through elegance and vulnerability. Our speaker can’t protect or help the moth, but she can set it in the grass, extending compassion through touch, trying “to ease what was to come.” The poem doesn’t end here, however; Brown brings our attention back to the human through the rattling of shopping carts, noting “how much each resembles a cage.” This refusal of natural purity reflects throughout the chapbook, lending a hard, almost grittiness to what would otherwise be the sort of pristine nature writing we may think of when we hear the phrase “ecopoetry.”

Similarly, the poem “The Scat of It,” published online in Thrush, elevates animal feces to a poetic subject, expanding our understanding of ecology as “household” and evoking a sense of astonishment. This poem may begin by describing scat as “shit” but quickly modifying it as “the beetle’s tumbling joy.” Brown finds beauty in this natural image, describing “that of the goat and sheep and rabbit” as “a pile of dinky moons eclipsed, a mess of shining beads, a black rosary // undone.” Here, excrement turns into prayer, and we realize it is—the act itself is a sign of nourishment and life. She reminds us that such a “bouquet of gratitude” is far from disgusting; that if we are ashamed of it, it is because “we have not yet / learned—blessed is that from which we came, blessed / to what we return.” We may never understand just how lucky we are.

The final poem of the collection, “Mercy,” which appears online courtesy of the Norwegian Writers’ Climate Campaign, expresses a desire to communicate with animals. Yes, there’s a certain naivety in such a wish, but believing it is possible is also an attempt to recapture what is sacred. Each stanza of “Mercy” grows more desperate to reclaim not only a lost language but a deeper connection to what so much of our culture is built around excluding:

Speak, sing to me, caw and fuss

among what brittle branches

left, I have opened my windows;

I am listening.

Speak, …

By opening her windows, our speaker has bridged the distance between two worlds, but she finds it’s not enough. Further into the poem, our speaker begs: “I need you / to speak, dammit, / speak.” This is language aware of itself as a process, coaxing, “[w]e can start with the low pleasure / sound, the delicious mmmm that closes the door to home.” Communication takes practice, and our speaker believes the way to understanding is through one word: mercy. Through language, we can strengthen our connection, to nature and to each other. By practicing mercy, Brown reminds us, our household strengthens. We’re all in it together.

Stacey Balkun is the author of Eppur Si Muove, Jackalope-Girl Learns to Speak & Lost City Museum. Winner of the 2017 Women's National Book Association Poetry Prize, her work has appeared in Best New Poets, Crab Orchard Review, The Rumpus, and other anthologies & journals. Chapbook Series Editor for Sundress Publications, Stacey holds an MFA from Fresno State and teaches poetry online at The Poetry Barn & The Loft. Find her online at http://www.staceybalkun.com/