terra venenum (2021)

Kel Mur

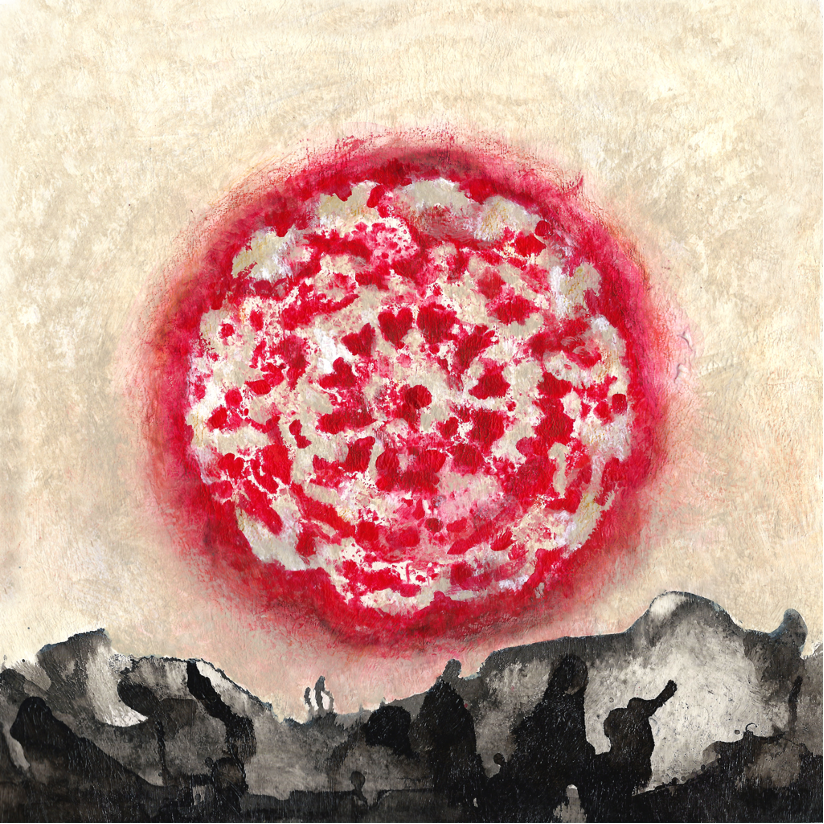

Stacey Balkun: Kel, I’m so happy to have this artwork adorning the cover of Sweetbitter. We grew up in the same town, a place that holds so much tension between nature and human forces. We played in the woods, but as kids, didn’t realize Union Carbide was manufacturing asbestos on the other side of the chain link fence. How do you see that tension coming through in this image?

Kel Mur: I feel like a lot of horrible things can be discussed within the realm (under the veil) of beauty. I think I made a “beautiful” image and I think much of the work I make has that kind of aesthetic quality. Beauty itself has very little depth, in my opinion, but it can lure a spectator into subject matter that they might shy away from otherwise. This kind of seduction is historically conflated with the feminine “tendency” to manipulate, and therefore breeds the idea that “females” are temptresses and not to be trusted. I find this is a fascinating toxic power dynamic trope, and I think it parallels themes in the book that relate to gender as well as the promises that big pharmaceutical and manufacturing companies make when they enter suburban towns like Piscataway. Much of which relates to employment opportunities or money, in general. Since leaving, I’ve always described Piscataway as a “highway” town. It used to be farms, which is why my parents bought a house there to begin with - so they could raise their children near that kind of idyllic scene. Now, it is a town that many pass through or commute from. To accommodate the traffic, Route 18 was extended directly into Piscataway around 2005 or 2006, which included the destruction of a much smaller trestle that crossed over the Raritan River into New Brunswick. I remember it as romantic, quaint, and passing through woods - obviously it could not withstand the increasing traffic. There used to be an empty wooded lot across the street from my childhood home not too far from there that we used to play in, now it is home to four bloated McMansions, a tale as old as time it seems, a familiar gripe of the old timers. I will say that I had to relearn my native landscape because of that construction, and routinely felt lost returning to my hometown.

SB: I love these thoughts about beauty as an entry point rather than a conclusion. I remember that as I learned to drive, I could still choose to cross the little bridge across the Raritan River rather than the big overpass; not only because it was “beautiful” but because it felt like a tie to something before me--a primeval place, intimate yet completely unknown. I think this image reflects a similar tension: the central object is a doily (something quotidian) yet it’s removed from its familiar setting (the domestic) and placed in a liminal, unknown space. Is it floating, or falling? Is it receding from the landscape, or entering? There’s a sense of timelessness, beauty, and dread in this image. The color palette here is simple yet feels overbearing.

KM: Red, black, and white will do that. It is one of the most classic, betwitching, and visually satisfying color combinations I can think of in design. I think the weight of the central round element, this setting sun of molten lace…the black is water and mountains at the same time somehow…the whole landscape is pretty yet foreboding…you can look but don’t touch, there are consequences. I think the strongest part, conceptually, is that the focus on the glowing center gives that part of the image all of the agency in the composition. I feel that’s a really strong connection to the content of the poems.

SB: Yes indeed! I love how when framed, this piece has the feel of the cover of a spellbook: it’s bewitching, mesmerizing, and a little terrifying. Do we even want to open this book, turn the page? It’s gorgeous yet ominous. One we turn the page, something else will claim agency and we viewers/readers are just along for the ride. I think the willingness to enter discomfort is crucial for learning and growing. In some cases, such exploration can be dangerous, and yet we both return to it again and again. So much of your work (like my work) is centered on toxicity. What does toxic femininity mean to you? How is this image representative of that?

KM: (The first thing that pops into my head with this question is the acronym TERF)...I feel like if we had known that we could be “they” back when we were growing up, many of us would have…just the chance to expand the knowledge and definitions of what our bodies meant and could mean…especially in heterosexual realtionships, or even beyond. Toxic femininity is similar to toxic masculinity in that it is an exclusive definition of what is or can be feminine, instead of inclusive. Living by these kinds of rules deadens our experiences in the world and limits our expansions of self. In a more fluid approach, more open concepts of masculinities and femininities and understanding that all manifestations of the body can adopt as many as they want from either group, I think, is a much healthier way to explore gender. Gender should not be something that is assigned (from the outside by another) but rather created (from the inside by the individual).

SB: I also love this idea of gender as something to be explored and created rather than assigned: it’s malleable, fluid, liminal. Do you think, then, there’s such a thing as transgressive femininity?

KM: Wow, that term really makes me feel things in my core. If we are talking about subverting something like “toxic femininity” or working against a binary from within a binary?...possibly? Then yes, I do believe there could be such a thing…and I will say that because it feels true to my identity. I think a lot of that notion can come down to how and to what we assign value. Traditionally, most of our social and economic value is placed on how well we adhere to the commodities that are sanctioned by our gender. When I see a male-presenting person in a makeup advertisement, I experience such a sense of relief. While it is still monetizing someone’s gender expression (hi-ho capitalism), it feels good to see that infiltration and departure of ownership over who can express themselves as femme and who can’t. I feel that within my own experience, some of the stereotypical femme things that I rebelled against in my youth, I have come back to reclaim. However, I’m not sure if that would feel so transgressive to me if I hadn’t explored things that I felt were at the other end of the spectrum, such as “defiling” my body with piercings, tattoos, promiscuity, using foul language, and embracing intoxicants, for example. All very unladylike things. I think it’s sad that at one point in my life, I wanted to make my body “less pretty” with those kinds of things so I could filter out assholes. Why couldn’t that have come from something more internal? But, all in all, it was a means of survival and protection, trying to find my way in the system. I think that I'm still trying to sort out what is genuine and what is rebellion and how much differentiation there needs to be between those two things. I think manifestations/constructions of my gender have been momentary or situational and possibly even reactionary at times. I'm not sure if that's true for everyone, but it feels true to me.

SB: I think this experience of adjusting one’s own body to make it less attractive or less visible is more universal than we’d think, unfortunately. Our bodies are our means of survival, and I can’t help but feel there’s a deep connection between the survival of non-male-presenting bodies and the survival of the environment. I know you’ve explored the connection between the land and body in your previous 3D and 4D work. What does that connection mean to you?

KM: I feel like land, body, place, and memory all have very blurry boundaries to me. My personal experiences have severed my connections with certain places (including Piscataway), and I feel as though my ability to bond to a place has only recently been restored, mostly by working with a particular plot of land in Oregon, WI, tending garden and landscaping for a side-gig (and rekindling familial relationships in Piscataway). I think being outside and witnessing growing cycles, harvesting cycles, and witnessing other forms of life in that scenario really brought me back to how we are all linked to similar cycles while hosting a body. I do not know what it’s like to be in a male-presenting body, but as a person who possesses a ‘birthing body’ which goes through cycles of fertility and menstruation, I see this bodily process as a micro version of the larger life cycles that surround us on the planet. The rhythms of planting crops, harvesting them, and then tilling the soil; or the life cycle of a singular plant, especially a flowering plant, where we can witness their sex as a point of beauty and visual pleasure (in the form of a flower). I am incredibly fascinated by the birthing body as a place of both life and death, one of fertility and of expulsion, one of incredible nurturing but also of lethal defense and hostility (as in the case of sperm traveling through it). These concepts are ones that myths are based on, ones both of reverence and great caution and fear. The sexual anatomy linked to these reproductive organs (I am most definitely referring to the clitoral bulbul organ) is also unique in that it is designed purely for pleasure and can experience release without any link to acts connected to reproduction. This is incredibly powerful, the weaving together of anatomy that can make another human but can also be solely engaged in attaining sexual pleasure without reproduction. It feels like there are parallel macro and microcosms all echoing each other at once if we pay attention. Separate from gender, the power of this anatomy does feel very ‘earthly’ to me. I am really interested in the apathy of nature and its momentum towards survival. In the binary/hetero/misogynous/hegemonic system, the presence of the clitoris is akin to nature’s irreverence and therefore perceived as a threat to systems that chronically hijack birthing or female-presenting bodies as a means to their own ends.

SB: Do you see a connection between poetry and visual art? What does the conversation between different mediums mean to you?

KM: This is a fantastic question. I don’t know who said this, but there is a quote that goes something like, “art makes it possible to dream while you're awake” and I feel that poetry does the same thing. I feel the two art forms are siblings, really. I think ‘good art has poetry to it, as in it has a rhythm, a feeling, and a part of it that is hard to describe. I’m not a poet, but as someone who appreciates that artform, I feel that words in a poem do something similar. They swirl around their topic like the wind carrying leaves, and they are woven like a tapestry - what I mean is they surround their topic or idea. They do not make it concrete. They fill the space around it, leaving the reader their own space to interpret and feel. I think art does the same thing. It makes space for contemplation but does not (and cannot, or even should not) do all the work for its viewer. The viewer must also be able to enter the work for it to be a success. I would also say all of these points could also be arguable, ha. Not every work will successfully provide a way in, and more than likely, it will also not provide a way out for everyone.

SB: Although it is powerfully unique, it’s easy to see how this piece fits into your larger portfolio. So much of your work is concerned with gender and the body. How has your perspective shifted over time? What are you working on now?

KM: I think about this often. My feminism bubble really burst around 2016 when I felt really confronted with issues that concerned the trans-gender community. While I studied different aspects of feminism and was making work through that lens, it was still easy to forgo being inclusive since I primarily identify as a cis-gendered person, or I at least do not experience any dysmorphia relating to that part of my body - if I chose. I realized that thinking about these issues made me reevaluate my own gender and my relationship to it, which I found liberating. I realized that since I adopted ‘Kel Mur’ back in 2012 or so, part of what I like about that pseudonym was how it felt gender-ambiguous (it also sounded like the name Wilmur to me, which still makes me laugh). More recently, when folks started to put their pronouns in Zoom calls and email signatures, I froze with a lot of anxiety. It felt like a declarative move to add ‘they’ to my pronouns. I fought with myself about it for a long time, but after a lot of thought about why doubling down with she/her felt immobilizing and unnatural to me, I decided to ‘out’ myself in that way. It felt like a huge deal even though I’ve been casually she/they-ing casually for years now, sort of on the down-low. When it comes to my work, it frankly gets messy rather quickly. Before grad school, I think I made pretty blatantly political work about the body through a feminist lens. After my mother suddenly passed, this complicated things for me. I felt a tug to make personal work, and sometimes this unintentionally took on an essentialist air to some of my transgender or non-binary colleagues. At the time, my focus started to turn inward and toward things like heredity, thinking about how my body came from my mother’s body, so some of the language that I used in my work, I think, accidentally took on a slightly exclusionary tone at times. Making work from such a vulnerable place and making personal work that maybe didn't give all viewers access to it was hard to take criticism about, but I did the best I could to listen and figure out how to make work that felt genuine to my narrative. Making work about the body, no matter how personal, can easily be politicized or is just inherently political. I think I arrived at a place that starts to balance this mostly by making sure that I’m talking about my experience in my body instead of trying to make a blanket statement about gender and female-presenting bodies in general. It can be challenging to know when to make those intersections between anatomy and gender in my work in a way that does not conflate the two. I’m sure that I have upset people on both sides of that equation, but I take it project by project. Right now, I am about to start new work, and I’m not sure what journey it will embark me on. I will say that I am even more interested in understanding my internal landscape and how it blends with the external world. I just finished curating a show about mental illness/health, and it made me revisit the state of my own mental health and experiences. I feel urges to retreat after the year I’ve had back in the world, as I’m sure many of us do, and I want to work from that place and create more intimacy with myself. I’ve been thinking a lot about self-portraiture, the paintings of Hilma af Klint, Carla Jay Harris, and Gustav Klimt, and what it would mean to start painting regularly again, and what that would even look like. I think a lot about how some painters are compulsive makers, and I envy that sometimes. I am learning, as a human and former east coaster, just how much quiet I need to make and to think, and I am trying to create this lifestyle of contemplation and personal sustainability. It feels like a search for quietness and understanding aspects of life that make me feel whole and full.

Stacey Balkun is the author of Eppur Si Muove, Jackalope-Girl Learns to Speak & Lost City Museum. Winner of the 2017 Women's National Book Association Poetry Prize, her work has appeared in Best New Poets, Crab Orchard Review, The Rumpus, and other anthologies & journals. Chapbook Series Editor for Sundress Publications, Stacey holds an MFA from Fresno State and teaches poetry online at The Poetry Barn & The Loft. Find her online at http://www.staceybalkun.com/