“Every time I write a poem I make a little body. … The poem-bodies—like all bodies—grieve and feel shame and sense things and exist in a certain time and place. The poems remember, the poems are erotic. The poems are bodies that betray us even as they save us.”

–Oliver Baez Bendorf

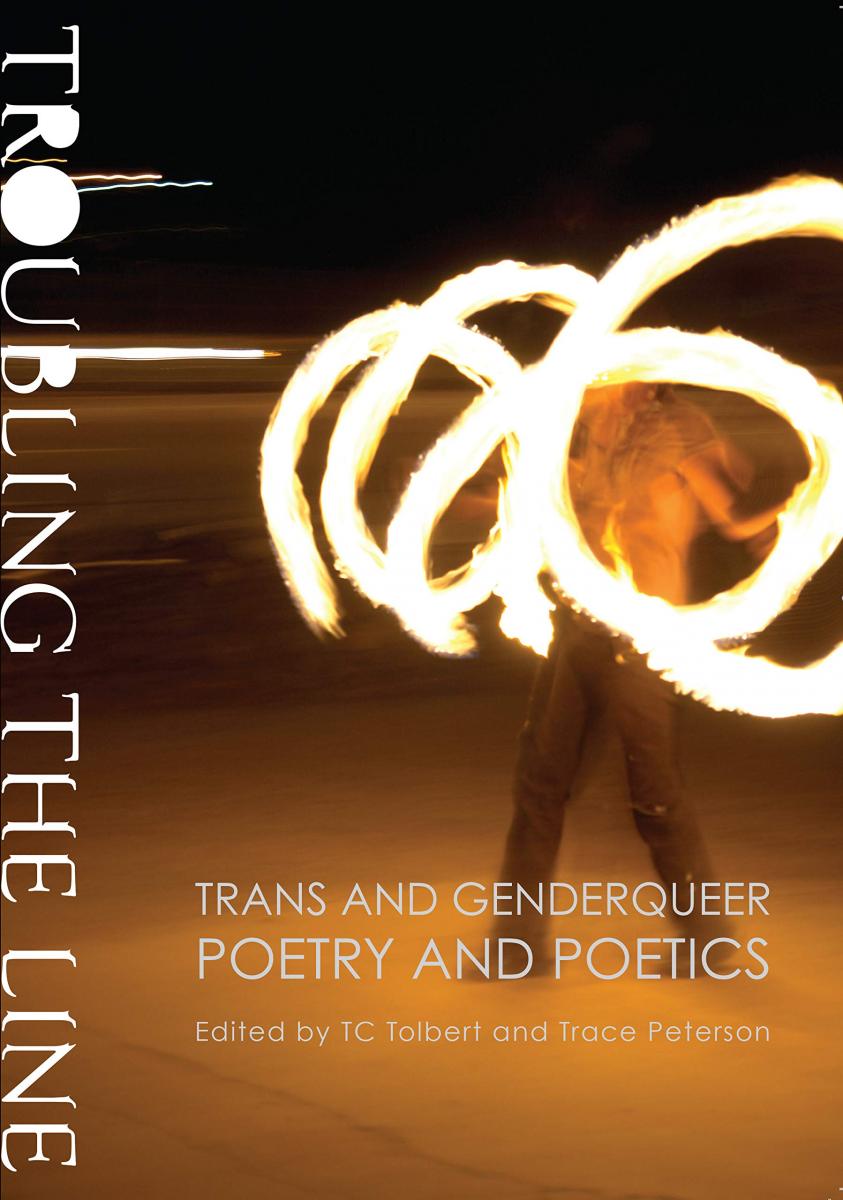

Edited by TC Tolbert and Trace Peterson, Troubling the Line is an anthology of trans and genderqueer poetry written and published within the last ten or so years [editor's note: before its publication in 2013]. In the “Introductions” (the pluralization is part of the chapter’s title, a la Jack Halberstam, to represent multiplicities of meaning), Trace Peterson explores trans text as a place of “possibility” and dialogue. She calls this book “an opening gesture to provoke what TC and [she] both hope will be a long and productive conversation” about genderqueer poetics.

I love thinking of a collection as a gesture, as an opening. Welcome, it seems to say: step inside and look around. Or, step outside and let’s see how much surrounds us.

Peterson’s introduction reads like a manifesto, and also like an anti-manifesto. She rejects definition, proving instead how genderqueer poetics is no one thing (except that it’s definitely not binary). Rather than set out to rigidly delineate the term genderqueer, Peterson offers us a refreshing sense of possibility. She discusses how the editors chose trans and genderqueer as “the most inclusive umbrella terms” they could find to describe “lived identities that challenge gender norms,” building bridges between rather than walls around the terminologies of identity.

“Words take on textures and supernal light, telegraphing strange, new points of entry—portals to visions”

–Max Wolf Valerio

To further this sense of collectivity, several of the pieces anthologized here are accompanied by poetics statements by the authors represented, allowing us readers to experience a wide scope of possibility: what does genderqueer mean to each poet? How do they each define “genderqueer poetics” for themselves?

Of course, identity becomes important here, and because form and content are inherently connected, so many of these poems are experimental and free: reaching across the field of the page, privileging blank space, including found text, using punctuation in new ways. Ultimately, the concern seems to be how the line on the page (like the “line” of the gender binary) can be manipulated to open up new spaces and better represent the concepts at hand, namely ideas surrounding identity and gender.

“I didn’t pose. // I had no choice but to pose.”

–Ariel Goldberg

One poem in this anthology that particularly struck me was Ely Shipley’s poem “Six,” which can also be found online here. While this piece doesn’t employ the experimental tactics of many other poems collected here, it beautifully compares bodies and instruments and poems and identity—it’s gorgeous in both its honesty and invitation to possibility.

Shipley’s poetic statement, “The Transformative and Queer Language of Poetry,” also begins by asking, “How does one begin to write a body that has been historically illegible?” Poetic language, Shipley argues, can allow us to pursue sensations that are beyond language.

I love this idea of using the flimsy tool we have (language) against and around and into itself to move somehow past its limitations. A poem, this anthology seems to argue, is an illusion of wholeness: if gender isn’t static or complete, how can the page represent it as such? Poetic language, Shipley says, “keeps possibilities for desire, for identity, for language, for new embodiments open.”

Genderqueer poetics allows for an allusion, a description—it can be both/and. Genderqueer poetics can be a “struggle toward a sense of self that will never be fulfilled,” at least for Shipley, and yet “that space of unfulfillment” can be a source, an opening. To write the trans and genderqueer body is to open a new space on the page, to create sound from a historic silence.

“The body is an afterword for what has yet to exist”

–David Wolach

Centered quotes are cited from various poetic statements throughout the anthology.

Stacey Balkun is the author of Eppur Si Muove, Jackalope-Girl Learns to Speak & Lost City Museum. Winner of the 2017 Women's National Book Association Poetry Prize, her work has appeared in Best New Poets, Crab Orchard Review, The Rumpus, and other anthologies & journals. Chapbook Series Editor for Sundress Publications, Stacey holds an MFA from Fresno State and teaches poetry online at The Poetry Barn & The Loft. Find her online at http://www.staceybalkun.com/