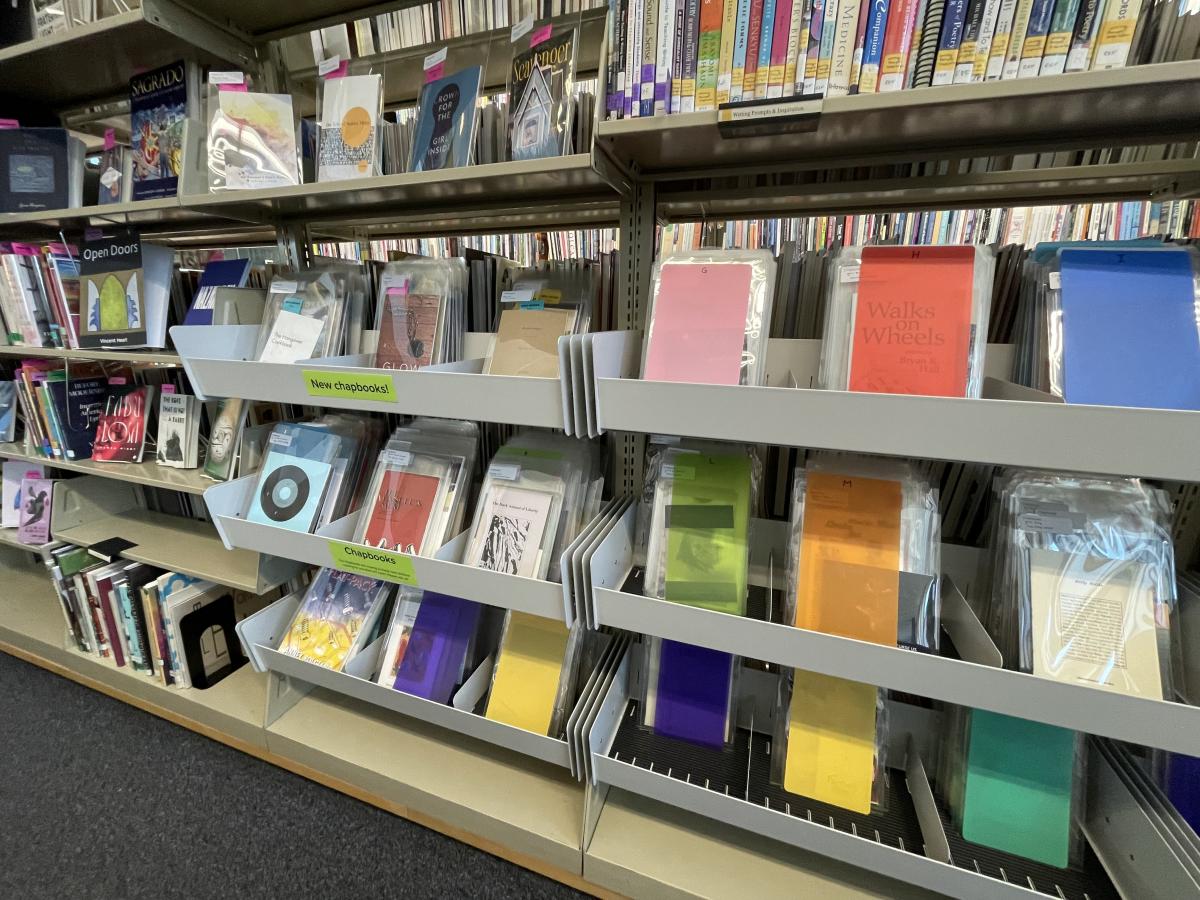

For the past four months, I’ve had the pleasure of working with our chapbook collection as an intern at the Poetry Center. For those who may not know, a chapbook is a collection of poetry shorter than a full-length collection typically, but not always, published as a poet’s first step towards a book or as a showcase of poems following one thematic concept. They are usually produced in limited runs which—from what I’ve seen in our collection—can range anywhere from 30 to 50, all the way up to 200.

However, since chapbooks are a unique subset of the publishing world, they can take many different forms: they can be made of hand-made papers, can be artists’ books featuring drawings or visual art, can feature multiple languages, can be perfect-bound, stapled, or even hand-stitched, and—in the case of one of my favorite chapbooks—can even be only one single page long, containing four lines of poetry, about half the size of a palm. Of course, chapbooks such as the half-palm sized one may cross over into rare book territory, but nonetheless, they’re wildly fascinating, and beyond delightful.

To paraphrase Sarah Kortemeier, the Poetry Center’s Library Director, poetry, and chapbooks by proxy, is not always the most financially viable, but because of this freedom from market constraints, poets are allowed to create beautiful things.As I handle the chapbooks themselves, I can see this freedom and its resultant beauty in the objects of the books themselves, this creation of art for art’s sake, so they say.

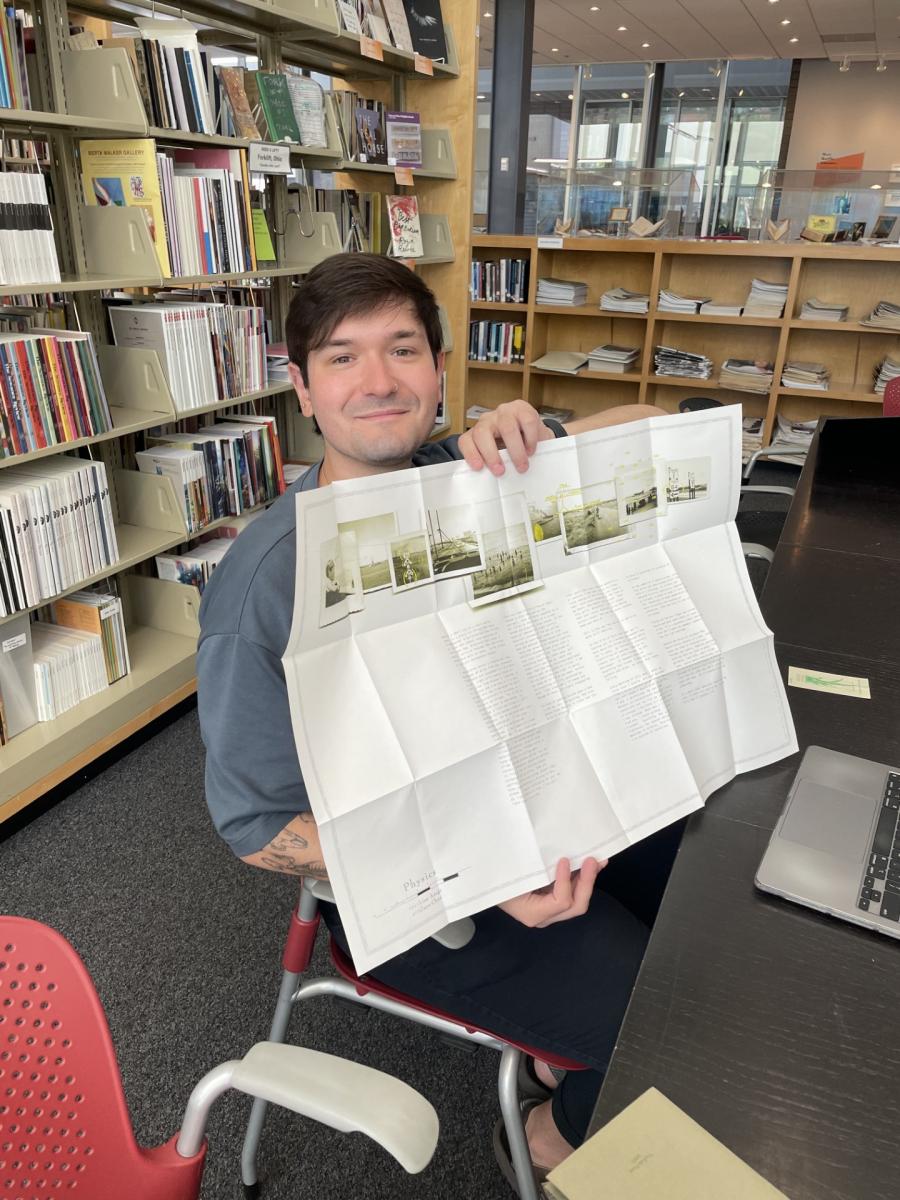

There’s something so intimate about holding the chapbooks, feeling their covers as they come out of their archival sleeves, looking over them and through their contents—there’s a closeness and proximity, both to the poet and the publisher, in reading chapbooks that I don’t think one can experience reading a regular, trade published book of poetry. There’s something so special in their physicality: when looking at the chapbooks that are staple or thread bound, I can see the physical vestiges of the labor that went into making each book. I can imagine the publisher, collecting the individual pages right off a press, laying the chapbook out, taking a needle and thread or stapler, and beginning to bind each chapbook together, slowly, methodically, with joy. It’s quite wonderful to imagine that—in holding the chapbooks—there are traces of other peoples’ hands right in front of you, traces of the labor of their love, and that by holding the chapbook, it’s almost like you’re holding someone’s hand while they bring art into the world.

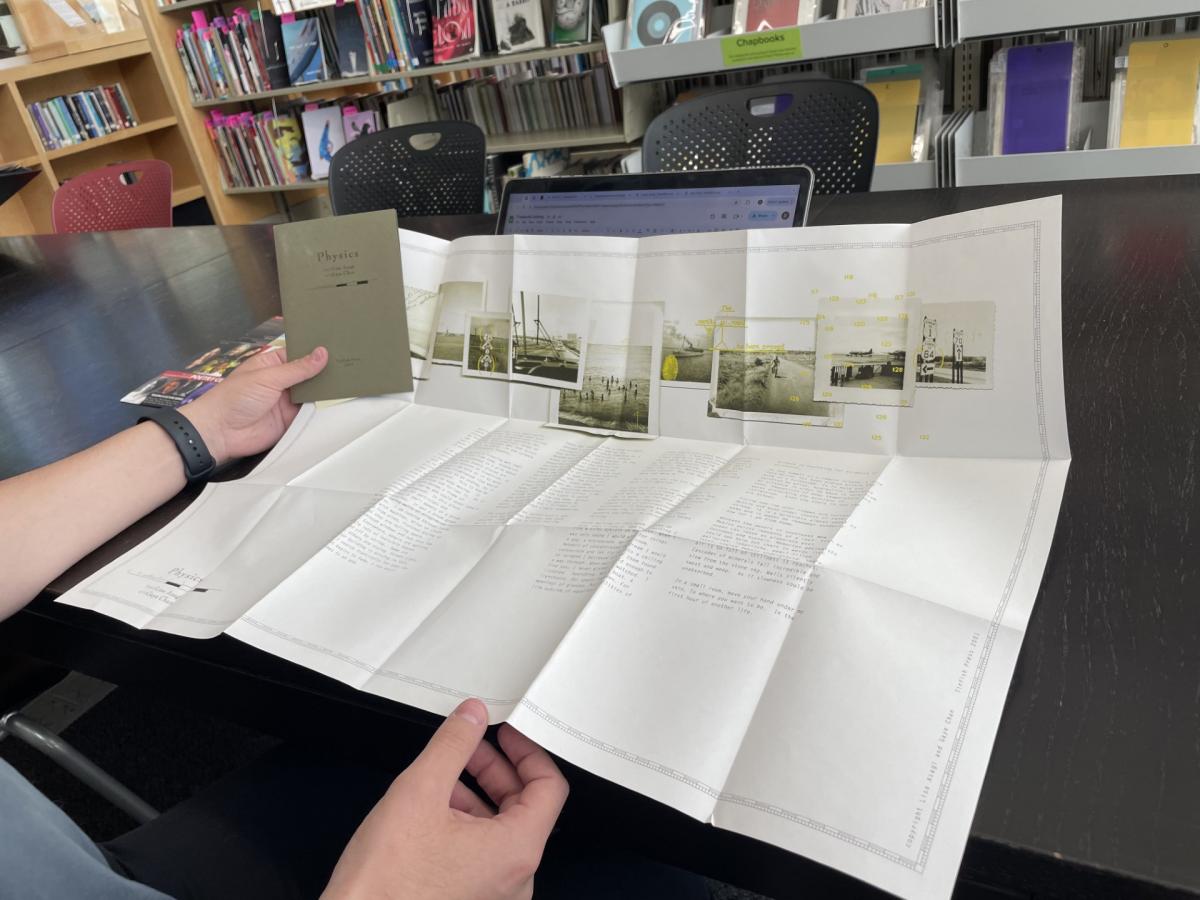

To give a closer look to our chapbook collection, I particularly loved one titled “Physics” by Lisa Asagi with artwork by Gaye Chan. When I first opened the book, I had a bit of a fright: the glue holding the text into the cover came loose, and the pages—or page as I would soon find out—plopped right out of the cover and onto the floor. My mind immediately went, eek!

I felt so bad, thinking that I harmed the book, but when I picked up what had fallen out, and began to look through the pages, I was surprised at what I found. I unrolled the work and noticed that all the pages were connected in one, single line, which kept unfolding and unfolding, until the book unraveled into one giant sheet of paper. It was almost like a broadside, folded up, chapbook-shaped. I discovered that the page was meant to come out of the book.

Later, after asking Julie and Sara what the book was, they informed me that it was something called a “map fold,” quite literally, when a book unfolds as one, big sheet of paper, and the contents look like holding out a map, as one would do with a geographic map if they were looking for directions.

The border around the text was beautiful, full of a series of lines and dashes which almost resembled the markings of measuring tape or a ruler. In the center of the work, there was a series of photos which spanned across the page (and across the United States), some of which I could identify and some of which I couldn’t.

To describe the images from left to right, there was:

- a picture of a man by the ocean with cursive writing in the background

- a picture of the statue of liberty

- a picture of highway markers in Nebraska

- a picture from the front seat of a van that showed a highway cutting through a city

- a picture of a group of people in bathing suits at the beach

- a picture of a what seemed to be a warship

- a picture of a person riding a bicycle on a dirt road

- a picture of planes in what could’ve been a military installation

- and another picture of highway markers, but from North Carolina

Coursing through all of the images was a thin yellow line, and other images, shapes, and fixtures in the same color, including circles around peoples’ faces, circles around the mile markers, fingerprints, arrows pointing towards objects and annotating them, words which read as lines of a poem, and a series of three-digit numbers counting, roughly, between 100 and 132.

I assumed these photos were from the artist collaborating on the book, Gaye Chan.

Beneath the images, there was the text of the poem by Lisa Asagi.

Throughout the text, one could see that the text was likely referencing Hawai’i, based on the publisher’s, Tinfish, mission to publish experimental work from the Pacific as well as lines located in the poem which conjured up images of the islands. These references also arranged themselves in what the text noted as a series of dreams or visions:

“In a film this year some one is leaning out of a window and wonders how much more the island will change while she is gone. An increase in pressure, electricity of engines, combine to create loss of consciousness in the passenger. It happens whenever departing the island.”

“At the summit of a remote island, a nine foot mirror has been placed within the mind of a telescope. It is held and adjusted by wires, hydraulics. Operated by distance in order to keep it safe from heat.”

In particular, one may have seen vestiges of Hawai’i in Asagi’s notes of the “nine foot mirror placed within the mind of a telescope,” and the mention of “the island changing while [one] is gone.” The mention of the “island changing” may have referred to any island in the Pacific, but the “nine foot mirror within the mind of the telescope” conjured associations of astronomical research and observation, which from a quick Google search, takes place mostly on Hawai’i’s Big Island.

However, Asagi’s lines complicated the speaker’s relationship to this environment. In particular, Asagi noted that the speaker is “[t]housands of miles from home. Greenwich,” which one could assume to be Greenwich, Connecticut, or Greenwich, England. However, there were mentions throughout the piece that someone who the speaker had personal relationship with was from the islands: “I am falling again into the night in which you asked me to follow you home. Across the clustering of a city gathered by the water.” The text also made note that “I have been unable to sleep since coming to this place. Your hand a small warm shark dreaming in the reef of my heart. How bodies can whisper. Ribs like gills. Breathing. I could almost hear your voice. Barefoot, slow moving across carpet. How you must have sounded when you were 8.” Throughout these lines, one may have seen that the speaker moved to Hawai’i be with a lover or partner via “following [them] home” and via the tenderness of some of the lines, the you-figure’s “hand” as a “small warm shark” located in the “reef” of the speaker’s “heart.”

All of these moments in the text showcased the speaker’s specific relationship to Hawai’i as a place which may not have been home, but may have been dear, due to their interpersonal relationship with the you-figure.

Another interesting aspect of Asagi’s work is the way in which they explored human being’s relationship to the natural environment as it pertained to Hawai’i. In particular, the poem examined a dream the speaker had: “It was a green dream with dripping walls of dilapidated factories. I am running through rooms filled with machines, miles of cloth hanging from wires, finished drying so long ago they are falling apart.” Here, in concert with Asagi’s descriptions of the natural environment of Hawai’i and the photos from Chan, one may have seen a critique emerge regarding the idea of development. Literally, the speaker ran through “dilapidated factories” fit with “miles of cloth [...] finished drying so long ago they are falling apart.” Here, the speaker offered images of industrial ruin and excess production, specifically products—the “miles of cloth”— produced, but never used, hence their “falling apart” out of excess. These lines entered dialogue with Chan’s pictures depicting American highways and cityscapes which could have been viewed, under this lens, as hallmarks of production, hallmarks of change to the natural landscape in the name of the development.

This further complicated earlier lines where Asagi’s speaker mentioned a woman’s fear in the “island changing while she is gone.” There was a felt fear of development located here—a fear that seemed to hinge on the erasure of previous landscapes, a fear that the islands will become filled with “the electricity of engines” thus causing a “loss of conscious in the passenger” whether that passenger may be Asagi’s speaker, the speaker’s lover, or even the reader themselves.

It is important to note, as well, that these images and concern of development were further complicated by the historical relation of the United States to the state of Hawai’i, how American colonists in alignment with Dole overthrew the indigenous monarchy of the islands, thus leading to its subsequent annexation by the United States.

Thus, the concerns expressed about relationships within Asagi’s “Physics” charted many aspects of the American psyche: movements across the country to follow love, attempts to build home and relation in a new place, critiques of America’s complicated relationship with colonization in the Pacific, and explorations of America’s propensity to throw environmentalism by the wayside to favor developments.

Shifting away from a strictly critical lens towards an appreciative lens, Asagi wrote some stunningly beautiful lines which advanced the ideas explored above. To showcase but a few of them:

“Science is searching for evidence of existence.”

“Even the stars in the sky are echoes.”

“Behind a small eye of a small world, there is a place for things that have disappeared.”

“When I was old enough to find you, I never wished. I watched. I listened. Searching. Not a boat. A lighthouse. For spaces between. For meanings of glances. Possibilities of life outside of equations.”

Through each line's sheer beauty, Asagi continued to explore the complicated nature of erasure and continued being in the Pacific alongside the, possibly, failed errands of overly-logical and overly-development oriented thinking’s ability to account for its hand in creating said erasures.

To return to discussing the collection as a whole, it’s been a wonderful experience working with Julie Swarstad Johnson, the Poetry Center’s Archivist, to increase accessibility of the chapbooks present in our collection. My primary duty in this internship has been to transcribe metadata, searchable information from the chapbooks, to be uploaded to our catalog, and then, to prepare the chapbooks to be placed out into the main stacks of the library. Julie has taught me so much about the ethics of archives and their central function—to paraphrase Julie, it’s important to do what you can to increase access to all our materials; always try your best not to impede someone’s ability to easily access a material. As she has further discussed with me, it’s important to increase this access not only for researchers to query our databases but also so the public is able to better access and understand the library’s holdings—so the public is able to come in, read, and enjoy a body of poetry hosting a constellation of voices.

_______

Dillon Thomas Clark is a writer, editor, and educator from New Jersey. Currently, they live in Tucson, Arizona where they are an MFA candidate at the University of Arizona and the former Editor-in-Chief of Sonora Review. They were a finalist for the Sandy Crimmins National Prize for Poetry hosted by Philadelphia Stories and have received support from the Southwest Field Studies in Writing program. Their work appears or is forthcoming in the tiny, Cobra Milk, The Milton Review, Broken Lens Journal, and elsewhere.