In the “Gezellige Poëzie” column, Laura Wetherington reports on poetry communities in Europe: festivals, independent bookshops and reading series, and innovations on and off the page. Read about the column title here.

On-Site Poetry: Tilburg, The Netherlands

Sander Neijnens and Nick J. Swarth in their studio

In 2005 a team in the Netherlands attempted to break the Guinness record for toppling the world’s largest domino course. They constructed the course in an exposition hall in Leeuwarden for more than a month. Enter a sparrow. Trapped and confused, the little bird knocked down over 20,000 tiles. The team hired an exterminator armed with an air rifle to do the only full-proof thing: shoot the bird. Animal rights groups were rightly livid and the incident made international headlines. It took four more years for the group to overtake the world record, one they still hold today. As for the sparrow, it has been immortalized in at least two ways. Nicknamed “dominomus,” or “domino sparrow,” the taxidermized bird is now housed in the Natural History museum (tagline: “a cool museum.”) Second, it’s the subject of a public poem created by the On-Site Poetry duo of Nick J. Swarth and Sander Neijnens.

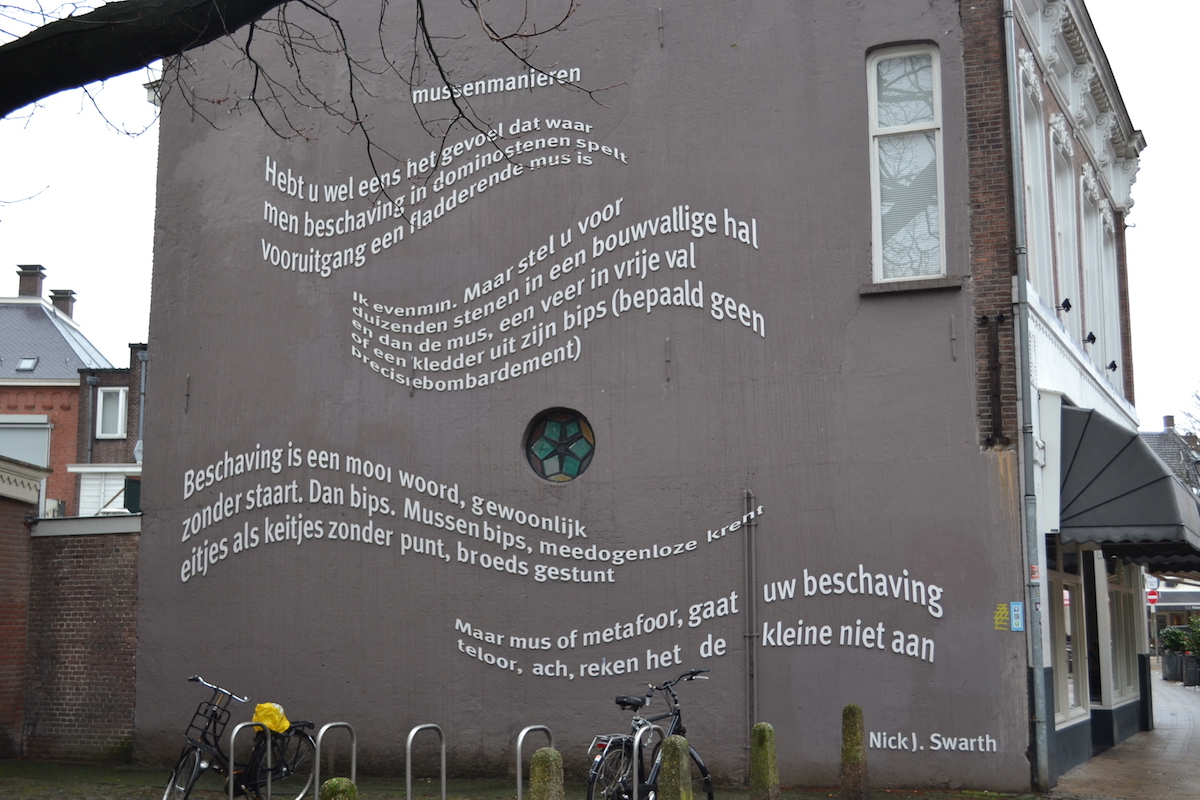

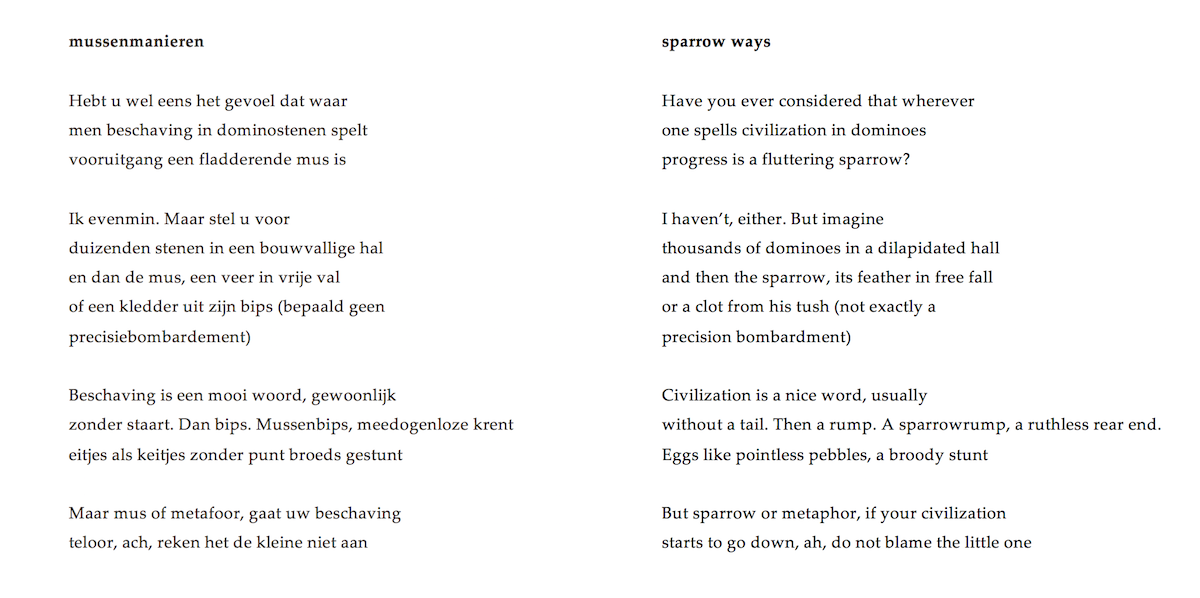

mussenmanieren / sparrow ways

There’s a strong tradition of public poems in the lowlands; they’re perhaps as proliferate as murals in the United States. They dress the sides of homes and the faces of restaurants, public buildings, sidewalks, fences—any place you can imagine, the words of poets are there. Still, On-Site Poetry has figured out how to set their work apart. While most of the poems you’ll see in the Dutch commons comes from existing material, the On-Site Poetry collective composes and designs site-specific, occasional installations. Their first collaboration, “mussenmanieren” or “sparrow ways” in English, provides the perfect example.

mussenmanieren by Nick J. Swarth / sparrow ways translated by Nick J. Swarth and Laura Wetherington

The tree shading the wall that would house “mussenmanieren” prompted Nick to call attention to the birds there, and the dominomus story was fresh in the national consciousness. Sander worked out a bird-like arrangement for the text using type that suggests movement—the stanzas here almost look like wafting feathers—and after two months of development, the project was approved by the city. Still, it took another year before the poem was installed.

The tremendous reception solidified the collaborators’ partnership. While this project came about during Nick’s tenure as the poet laureate of Tilburg, the two men had known one another for a long time. They met in the eighties when they both worked for Tilburg’s leftist action paper, TAC. Activism is a key component of their work. Nick explained that in the beginning, “the city center was mostly ads. You’re told to come into a shop, or you’re given some kind of regulations. Stop. No right turn. And we wanted to create a text that’s different.” On the subject of “mussenmanieren,” Nick explained, “This immediately evokes a much broader discussion: what is civilized to one person is meaningless to another. One man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter, et cetera. Any civilization is a construction (or a set of constructions) which can be threatened on all sorts of levels, and usually is. And you can always designate one particular scapegoat, but then you do not do justice to the complexity of societies.”

Their collaborative rhythm has evolved over time, adapting to each new environment. For their most recent project, they held several generative workshops with community members in order to draft the two-story poem that now covers the stairwell in a community center. When they worked with a festival on one of the northern islands, they used wooden disks from recently felled trees and orange peels from the festival’s extensive morning juicing routine. For these land art installations they first locate a site, then Sander calculates how many letters fit, and then Nick had his constraint: Sixty characters.

Oerol, Terschelling. photo courtesy of On-Site Poetry

But their activism isn’t just embedded in their content; it’s also in the presentation. “Other people use light to make public works interesting,” Sander pointed out, but “type and design is more about the space constraints.” Sander’s designs engage questions about legibility. “It’s about the magic of type. It’s about reading.” The snaking path of the orange peels are meant to mimic an animal trail, and “you can walk through it, but you can’t read it. You’re too close to understand, but when you get distance, you can see it.” Their installations address culturally significant moments, like population density and immigration in the Netherlands. The On-Site duo wants to promote the idea that some people might be too close to the issue to see it fully. On one poem painted along the slats of a fence, part of the text is in Arabic. Another poem, playing on the exclusionary term “illegal alien,” simply says, “Welcome Martians.” Sander pointed out, “We’re in a time when refugees are coming here and we want to promote the idea that there’s room for everyone.” The idea of legibility runs through almost all of their projects, like with this poem hidden under a drawbridge.

Here the water laps from now to later. The open bridge is a passage at this site on the river. A silence crosses your dream.

You can see more of their work at http://www.onsitepoetry.eu/index.html.

Laura Wetherington’s first book, A Map Predetermined and Chance (Fence Books), was selected by C.S. Giscombe for the National Poetry Series. She has a chapbook forthcoming from Bateau Press, chosen by Arielle Greenberg for the Keel Competition. She teaches in Sierra Nevada College’s low-residency MFA Program and co-edits textsound.org with Hannah Ensor. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.