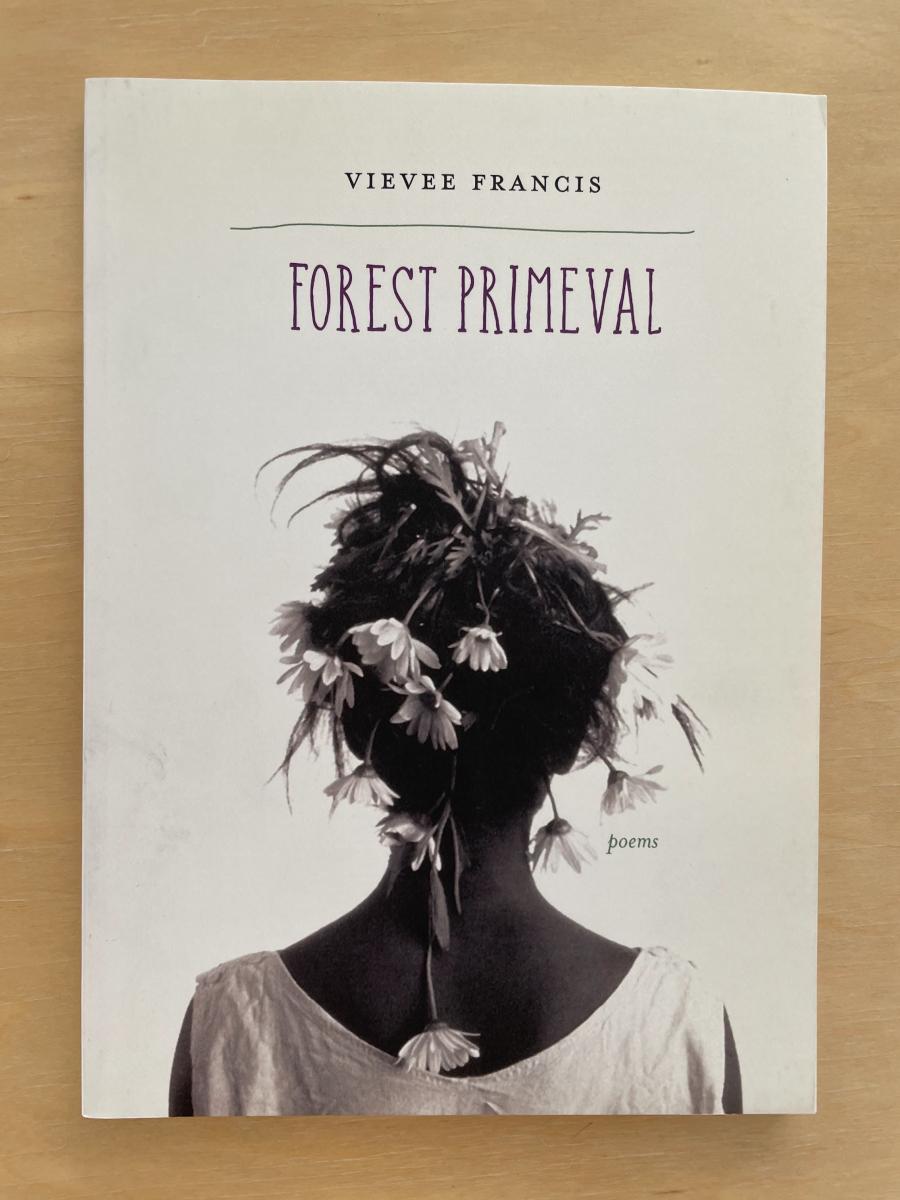

Maybe it’s because I live in south Louisiana—a culture so dependent on its environment yet at the mercy of climate change—, or maybe it’s because I grew up in a secretly polluted forest, but I am drawn to ecological writing. Not “environmental” writing but ecological—poetry that understands the way systems operate, the entanglements of human and more-than-human connections. I love reading contemporary poets who write at the intersection of field poetics and ecological thinking, in both form and content: poetry that undoes the binaries of human / wilderness, pastoral / disturbance, sustainability / destruction, violence / intimacy, and the body / other. Vievee Francis’s award-winning collection Forest Primeval, published by TriQuarterly Books in 2016, feels like a fitting example of such poetics in its adoption of creative forms, poetic embodiment, and attention to the landscape of the American south.

Deft with language, daring with rhythm and form, Forest Primeval explores the stitch between violence and intimacy, using the speaker’s Black body and its surrounding Appalachian environment to exemplify to explore the wavering spaces between violence and intimacy, humanity and animality, and other expected binaries. These are poems of liminality, of intersectionality. They embody so much, creating an ecotonal space of overlap, if only for the moment it takes the eye to move across the page or the mouth to sound out each syllable.

We can think about the form of a poem as its body, and the page upon which it is written as the “field of the page” (to borrow a favorite term from Charles Olson), then we can consider the form in relation to content: our speaker’s body moving through a landscape is also a body in a field. We “needn’t position embodiment counter to poetry,” Scott Knickerbocker claims in Ecopoetics.

Francis’s speaker often embodies not only pain, but also story, music, the past, and the future. Poems like “A Song on the Ridge” stretch across the page, describing the self and the environment through vivid descriptions that highlight insecurities, disparities, and the fallacy of the binary. “A Song on the Ridge” uses repetition, rhythm, and rhyme to create its own contrapuntal form while paying homage to the blues. Each line of description is followed by the same refrain after a brief caesura. Each line is double-spaced. The formal effect is that the first ten lines of the poem appear to move down the page in two distinct columns before they break into a less-stable format for the final five lines:

I was a spinner and a speller, a seller and deceiver back on the Ridge

I was a thief and the theft, a weaver and the weft back on the Ridge

A tiller and a teller, a sipper and a slipper back on the Ridge

The list of verbs used to describe the speaker embodies paradox and multitudes: she is both “thief” and “theft,” implying that she has both stolen and been stolen. Criminal and victim. Aggressive and passive. History, the poem reminds us, lives in our bodies.

The poem begins to turn in its third line when the descriptors of the self turn to nouns rather than verbs. Our speaker becomes “the secret and the spill, a spider and the wound,” not only interrupting the syntactical pattern but breaking from the rhyme scheme as well. This aural shift draws our attention to the final word: “wound.” To have been a wound is to embody pain, to accept a disturbance, a moment of being un-done. It’s to trust in healing: futurity, perhaps with a scar.

A wound is also an ecotone: a space where outside and inside meet, overlap, even mingle. Whereas skin often holds the boundary between the inner self and the outside world, a wound allows for trespass: what is held within the body is let out, and what is separate from the body is let in. The body meets the field.

I was the secret and the spill, a spider and the wound back on the Ridge

I was a seer and a swiller, a quail and a hound back on the Ridge

I heard the music and I sang it—a symphony of bark back on the Ridge

I threw cards and the bones upon a potter’s wheel back on the Ridge

Though the entire poem takes place in past tense, many of the self-descriptions allude to fortune telling. She has been a “seer” and has thrown “cards and the bones.” These simple words contain multiplicities of meaning: to throw cards could be to deal, as in a game, a gamble. It can also be to consult the tarot deck as a means of divination. Likewise, to throw someone a bone is to give a small reward, but could also allude to osteomancy, a form of divining the future from reading a selection of small bones dropped from a hand. Our speaker’s preoccupation with the future by describing her past accentuates the omission of the present.

I sought shadows and the shade. I was not afraid back on the Ridge

I was the fiddle and picker, a wife and sinner back on the Ridge

I was lightning over water, the cross and a believer back on the Ridge

Questions we could ask of a narrative poem include who, what, when, where, and how. This poem doesn’t answer these prompts: we don’t know where we are now, what’s happening currently, or who our speaker is in the present moment, only the environmental location of these actions and divining.

“The relationship between language and nature is, after all, far too entangled

for mere representation, demanding that we look ever more carefully at

the many forms this relationship takes, always complex and often beautiful.”

—Scott Knickerbocker, Ecopoetics, 185

I think this strange take on temporality is representative of ecological thinking: there is no stasis, no simplicity. The future is shaped by the past, and the past contains multitudes, ironies, and juxtapositions. The relationships are far too entangled for a “closed” form poem, or even a straight narrative poem. The form reflects the entanglements of her body and its environment as an ecotone where the two entities overlap: it is less a ridge a more a rift, or a wound. The poetic form allows the speaker to embody her experience, her environment.

back on the Ridge

back on the Ridge

back on the Ridge

back on the Ridge

back on the Ridge

Formally, the last five lines of “A Song on the Ridge” represent entanglement by removing the rigid column structure and instead enmeshing the two halves of the poem with the repetition of “back on the Ridge” at different indentations. We readers must “look ever more carefully at the many forms” this poem takes. In these lines, past and future are now stitched together, closing the gap of the page like a suture to a wound. The supposed binaries are actually actively intertwined, and this understanding shapes the poem through organic formalism and embodiment. It is both complex and indeed beautiful. The form is the body situated on the field of the page: two columns that are equal yet different, separated yet mirrored, and fully entangled by the final lines.

____

Stacey Balkun is the author of Sweetbitter & co-editor of Fiolet & Wing. Winner of the 2019 New South Writing Contest, her work has appeared in Best New Poets, Mississippi Review, Pleiades, & several other anthologies & journals. Stacey holds an MFA from Fresno State & teaches online at The Poetry Barn and The Loft. She lives and writes in New Orleans.