This year, I am going back to poets and poems that marked significant moments in my life, beginning with Lucille Clifton’s Blessing the Boats. (Editor's note: You can listen to and view many poems by Clifton at our audiovisual archive Voca here.) Reading so many of Clifton’s poems together is a seminar in the craft of compression. Hers are small poems: often short stanzas with even shorter lines. Everything is small—not even the pronoun “I” is capitalized—and the effect is one of tension. The disparateness of the form seeming so inconsequential and the gravitas of the meaning of each poem results in power. What may seem minor or intimate becomes large and powerful; what’s personal becomes political.

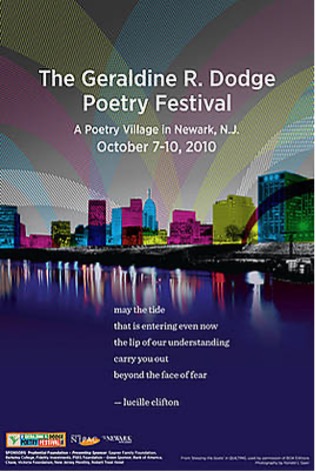

I’m especially struck by “blessing the boats.” An excerpt from this poem donned the poster of the Dodge Poetry Festival in 2010, the year it moved from a rural location into downtown Newark, NJ and the first Festival after Clifton’s death. Clifton was always a part of the Festival, for me, personally. I remember seeing her read as a high school student, and being enraptured by how powerful the simplicity of her verse. I would try to write love poems styled after her and of course be admonished for “telling not showing” or not following grammatical rules. It’s not easy to make something look so easy, and I admire Clifton for that.

image from dodgepoetry.org

The Festival’s move to Newark allowed for accessibility: high schools that could never afford a bus could now walk to the events. Citizens of the tri-state area could take a bus or train. Poetry would be brought to the people rather than the other way around. Planning an urban Festival required a very different sort of logistics, and a good amount of faith. From my perspective, “blessing the boats” felt like both a prayer and an offering: “may the tide / that is entering even now” the poem opens, “the lip of our understanding / carry you out / beyond the face of fear” (82). I love the syntax at play here: “even now” makes the action so immediate yet infinite. “Fear” becomes not something to avoid or conquer but to move through and beyond on a tide of understanding.

Clifton’s line breaks are unique in their effect, especially in this particular poem. I remember hearing her speak once, and when asked about the size of her poems, she responded with something along the lines of: “Have you ever raised children? When your only moment of quiet is shutting the washing machine, you write quick and short.” That story and image stuck with me. It was a little gift of wisdom: time is a resource; use it wisely. It was such a gift to hear her perform for the Festival audience. The way each of her small poems held its own against the thunderous applause it would be met with was extraordinary. You could feel the reverence in the tent for her and her work. I offer here a video of her Festival appearance in 2008.

As you can witness in this video, love and joy that resounds in these small poems, along with the pain and brazen political boldness. The tension she manages to capture in her small lines is incredible. I’m lucky to have met her (briefly) at a Festival book signing in 2004. Above her signature on the title page, she wrote only “For Stacey: Joy!”

Stacey Balkun is the author of Eppur Si Muove, Jackalope-Girl Learns to Speak & Lost City Museum. Winner of the 2017 Women's National Book Association Poetry Prize, her work has appeared in Best New Poets, Crab Orchard Review, The Rumpus, and other anthologies & journals. Chapbook Series Editor for Sundress Publications, Stacey holds an MFA from Fresno State and teaches poetry online at The Poetry Barn & The Loft. Find her online at http://www.staceybalkun.com/