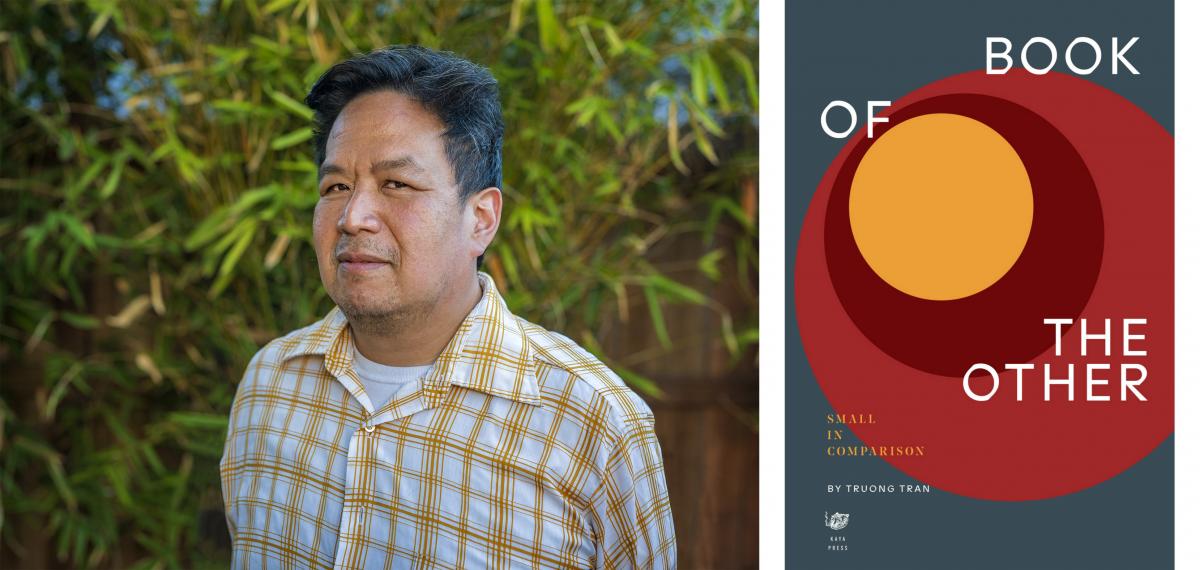

Truong Tran was born in Saigon, Vietnam, in 1969. He is the author of six previous collections of poetry, The Book of Perceptions, Placing the Accents, Dust and Conscience, Within the Margins, Four Letter Words and 100 words (coauthored with Damon Potter). He also authored the children's book Going Home Coming Home, and an artist monograph, I Meant to Say Please Pass the Sugar. He is the recipient of the Poetry Center Prize, the Fund for Poetry Grant, the California Arts Council Grant and numerous San Francisco Arts Commission Grants. Tran lives in San Francisco where he teaches art and poetry.

Putting It Down: A Conversation with Truong Tran & book of the other

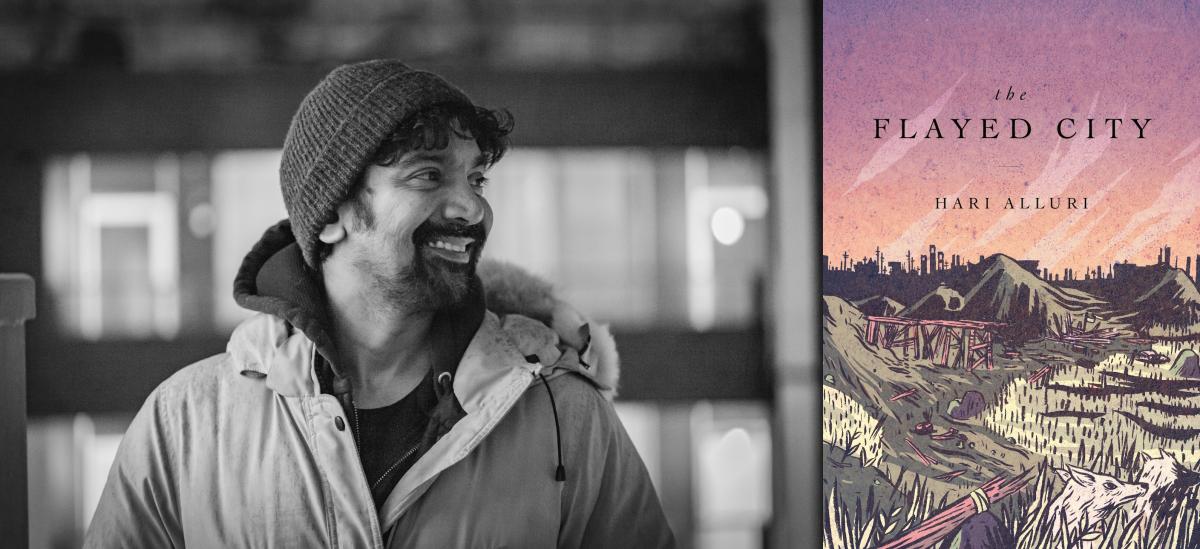

Hari Alluri: In reading book of the other: small in comparison, Truong Tran’s new collection of “essays. prose. poems. and antipoems” from Kaya Press, I was making notes on every page, moved and troubled, engaged throughout. The work in the telling, in the language and Tran’s treatment of language, driven as they are from deep, called up and affected my relationship to the languages that live in me, the ones that invited themselves, the ones that I’ve invited—on purpose or by implication.

Partially through the book’s accumulations and repetitions and singular punctuation, partially through how Tran implicates the writer and the reader, doubling them in the you and at times in the i, I kept being returned to certain passages—and in these verbs and senses: they struggled and spiralled me; sent me into a process of attending to the ways I have been grammared, the danger I feel in that grammaring process: the ways my body tensions into languages, the ways embodied intonations grammar a body. My body, I mean. Shameless pun, but true: the work reverbs.

book of the other began to transform me, and the conversation I had with Truong Tran continues and expands that transformation: may I never be the same again. This is one moment from the book that kept returning to me before, during, and since our conversation:

“it is just a thing. you tell yourself. you carry these things. they are placed on you. they are thrown at you. you walk through life. you are carrying these things. you anticipate a time. when someone is compelled. to correct your grammar. again it happens. and you collapse under the weight. you are buried beneath. a lifetime of these things.” (33)

*

(Note from Hari: Throughout this text, I interrupt our conversation with moments from the book, because I felt the work resonating alive as we spoke: Tran put so much work into what he had to say and how he had to say it. I juxtapose and in doing so rearrange, but our conversation actual was a flowing thing. We shared stories, experience, process back and forth. We kept ending the conversation and then either we just started up again or I had something more to ask, another moment from the book to share back, and Truong had generosity in each of his responses.)

We began, after our greetings, with me reading, to Truong, one of the “book within a book” passages, a series in italics that interrupts and converses with the body of the book.

“you are afraid of reading this book. you are afraid of writing this book. you are the stranger inside this book. you are the stranger who asked for more... you are the condition. you are conditioned. you are the reader inside this book.” (102)

Truong Tran: Our culture is so prefaced on this notion of courage and bravery in relationship to truth, isn’t it? “You are so brave for writing, so courageous for saying..,” I get that feedback as it relates to this book. So much that it sets into precedence a culture of silence and fear: if truth is such a courageous thing, it must be scary. How do you hold that elevation of truth and still write the thing that needs to be written, that exist in everyday life. Truth should be as easy as breathing and laughing.

“this is not about the academy ... this is about living. this is about seeing. this is about breathing.” (229; footnote 46)

TT: I wanted to write into that, and to write something else.

“when you give up. you begin again. you write. you tell. you document this story. when this is your story. when this is the way. you will find a way back.” (24)

HA: I feel like the “something else” happens partially through the repeated beginnings...

TT: The book is a constant series of beginnings because the harm that’s happening in it, it’s happening again and again: in the university and in the world. If I thought it was just about the academy I wouldn’t have written it.

“it is not academic. it is arriving at the knowing. it is not knowledge. it is not the arrival. it is lived. it is not a fair race. it is race. it is exhausting. it is fucked. it is private. it is the surface. it is whats beneath. it is living.” (71)

I remember a student saying, I did not sign up for a Poli. Sci. class. I thought this was supposed to be a poetry class—but you have students inside this space who can’t put the experiences, the struggles that are being called politics, down to step across the threshold. They don’t have the luxury or privilege of doing that. They carry that in their bodies, in their consciousness, and to ask them to leave that at the door is a conscious and willful denial of those struggles. We’re not crossing that threshold so that we can write about flora and fauna.

“i do not get to choose my politics. i do not get to choose my fights. i do not get to look away. i do not get to hide in language. i do not get to sit this one out. i do not have a choice in the matter. you do not get to ask this of me.” (76)

TT: No matter how difficult, to hold space for that reality.

HA: The notion of poetry apart from the consciousness of the world, the conditions of apology—I think you said in the book—that folks, that we are placed into.

“sometimes an apology is just a condition. of being. immigrant. other.” (45)

TT: What are we carrying? What are we caring for?

(Hari: I remember a page (123) that retells an instance with a Vietnamese student, the way the hunger in a poem they share turns from home towards here. Not just here, the conditions of here. And I’m thinking of the conditionality of being here—inside the selves that are other and so—denied the place of self).

*

HA: There’s also a returning to silence throughout the book.

TT: I used to think of silence as a craft in writing but how do you teach that in a classroom when silencing is happening to you? How do you convince the students they can invoke it as power while seeing yourself powerless, silenced. I saw myself in the classroom, teaching while silent. It felt like an out of body experience.

“i am only retelling this narrative because silence is simply no way to live. silence will not move this body forward. i am retelling this narrative as a way of being.” (94)

The silent treatment only works when the world you exist in sees your voice as something needed. That in the absence of your voice, they will ask for your contributions. That was perhaps a projection of my desires, it was the illusion I held onto that I still belong: that sense of belonging is not present...

“even with all that has been said. inflicted. endured. there is still no feeling like that of being present. in conversation and in community with those who hope and want to see their words existing in the world. this is why. always why.” (221; footnote 20)

*

HA: I’m thinking about page 106—“why is there shame. in wanting to belong.”—I’m afraid to talk about belonging: may we please talk more about belonging?

TT: The consideration of belonging happens in that moment when the camera turns about on itself and I am confronted with my desires of belonging and my willingness to contribute to that construction of whiteness. This desire to belong has been so ingrained into my consciousness as the immigrant, as the other.

With regards to this book, the reality is no other publisher could have published this book because I needed the hard questions. I needed to be challenged not by a white perspective but rather by someone who was standing next to me. Kaya is a press working with our community. Again this led me to a consideration of my belonging. I say of the book, it wandered and found its way home.

I had written what happened to me the first time, in 2006, in Four Letter Words, in coded language. One thing that I’ll never forget: the person I wrote it about invited me into their classroom to read from that book. They felt comfortable enough. They didn’t see themselves in the book! After a third rejection for a position of tenure track in that same department where I’ve been working as a lecturer in 2014, I knew I would have to write this book in no uncertain terms. In a way, it’s taken me the 15 years to write, to live, to endure this book. The late great Wanda Coleman told me this: “if you give someone the opportunity to not see themselves, they’ll take it.”

So, I set out to write this book with the constraints of honesty and the insistence on saying what I needed to be said.

I arrived at what I thought was the end of the book and still I needed to answer the question of why? My editor from Kaya kept asking why. So many iterations of why. And so I wrote another book inside the footnotes. I wrote them as a way of answering the editor at Kaya. It occurred to me that her asking why was a different and specific asking—because it had been asked by someone in my own community. And not by “colleagues,” by the white presence of the academy. One person actually approached me and wanted to tell me that I was committing career suicide.

HA: as in, that you could veer out of this book?

TT: As if I could veer out of this life.

“i could sense the kindness in their words. the awkwardness in between. something happened in that instance. in mid sentence. something had to break in this way. i said to this person. im asking you why.” (229)

The white why is about positioning themselves in the context of this world and work, it isn’t about me, and that’s the difference, like how underneath the question, where are you from, is the statement, you’re not from here. I’m here. I used to answer by stating where I’m from and how long I’ve lived here. Nowadays, I simply respond by saying I’m not leaving.

“always im aware of what this means. to be the only. to carry this weight. to know this. and still insist. on being present.” (227).

*

(Hari: I didn’t ask Truong during our conversation about the connection between presence and the moments of experience, especially of shame, that called him to “commit this to memory.”)

“someone will question the language. the grammar of this text. somebody will query the use of tense. how do you lineate this past this present when this happened. when this happens when this is happening. even now.” (89)

It’s an act of shame enacted and transferred to the person who is inflicted. That what I saw clearly as discrimination happened to me, but that act of shame is transferred onto me, because I’m expected to carry that in silence: you don’t talk about those things. Looking the other way is their silence and their shame, but I carry it, and writing this book was an attempt to put it down.

*

HA: I feel like part of that works through the way you use the period: I feel it so much: I’m scared to read displacement wrong here, but let’s see where it takes us: the displacement the period does to other punctuations, it seems to insist toward, maybe, an end of displacement.

TT: Yes, I decided to punctuate this book with the single period. I called it the policing of grammar—I originally asked a former student, a CIS-identified white man, to punctuate the book. I appreciate his willingness to do the work, but why did I ask him to take that authority—and why have I doubted my authority? The work evolved and within the course of all these years, I found my way back to the period. It became something else, when I allowed myself to take it on, it became a blunt instrument, both a hammer and a spoon for digging out of prison. The period became the enacted embodiment of punching my way out.

“the grammar of this book is the period in excess. this is of my own doing. that i am now. the reader. of this book. i am the enactment. singular. obsessive. excessive as a means. of getting through.” (131)

And, because it was a fight, I struggled toward the end. There was no power in it, like in the 13th round of a 15-round fight. And having to dig down to make my way to the end.

“inside this book. the period declares. that i am the prisoner. the period as facts. that i am stating. i am punching my way. toward the promise of an ending. of ending. this violence.” (125)

*

(Hari: My parts here are after our conversation)

HA: Hi Truong,

There’s so much in our conversation I plan to carry with me, not least the way I’m thinking now of the period as a kind of treatment, not the same as in a photography lab but that layering of work, of a type of labour. And it affects, everything. So maybe it’s a kind of wash, that doesn’t wash out it washes in.

“my student he said. i cannot afford. the luxury of metaphor. and just like that. i was changed. my student she said. for some. the metaphor is. a necessity. and just like that. i am changing. again.” (186)

And that changing is alive. In how you shared that anecdote about the conference, how it becomes a luxury when someone only needs to articulate their interests and someone else has to articulate their survival. And how not to do so becomes dangerous. And I’m changed by the ways your book refuses and refutes certain (silent, ventriloquized) notions of immigrant voice, how its tellings enacted, with the period, a digging under and beyond them.

And beyond, I’m thinking of the moments we riffed, on boxing, on our experiences gardening and landscaping, on care. Which means I’m also thinking about the moment of intimacy on page 117. And the way you offered this, at one of the several endings of our conversation:

TT: Bhanu Kapil’s recent book How to Wash a Heart, that work reminds me of when my friend Wanda Coleman said to me that abstraction gives the opportunity for racism to hide—I debated that and have come to feel it, that it makes perfect sense.

“and just like that. abstraction is a luxury you can no longer afford. it is a space to hide in. shapes and colors and the labyrinth of language. safe. perhaps. but hiding is a luxury.” (47)

TT: Bhanu’s book seems to carry that knowing: the clarity is just remarkable.

HA: And this book. It’s so generous, even when it’s fighting, necessarily—because of the need to attend to rather than perform the anger, because of the need to simply report—against its own generosity. I fear the word offering here, and yet it’s that, atang we say of the food we place on the altar (have you read Patrick Rosal’s project of that name?). Atang is like, unconsumable. As in, offered to the spirits, ancestors, and then eaten by the offerer. It’s food, so it must be eaten, but not simply consumed. And because it isn’t for the one who eats it, the eating is maybe also a kind of sacrifice? Definitely an offering.

“i am offering up my name... should you falter when spelling. remember that u comes before o. my name is Truong Tran. i will carry what is mine. and only what is mine.” (92)

Hari Alluri is the author of The Flayed City (Kaya) and the chapbook The Promise of Rust (Mouthfeel Press). A recipient of the Leonard A. Slade, Jr. Fellowship for Poets of Color, he has received grants from the BC Arts Council, Canada Council for the Arts, and National Film Board of Canada. His work appears widely in anthologies, journals, and online venues, recently in Apogee, Asian American Literary Review, Four Way Review, Split This Rock, Witness, and elsewhere. He is currently Writer-in-Residence for The Capilano Review, on the unceded and Ancestral Lands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh.