In Poet's Corner, Tucson Poet Laureate TC Tolbert shows us several drafts and revisions of a poet's work, then speaks to that poet about the writing process.

Poet's Corner with Saretta Morgan

Draft 1

Draft 2

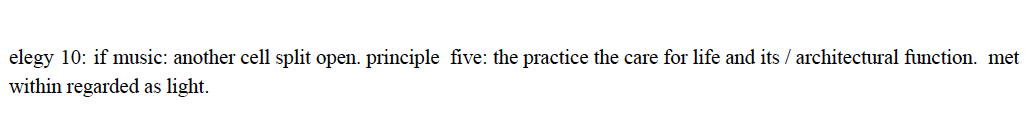

Draft 3

Final Draft

Questions and Answers for Poet’s Corner

TC Tolbert with Saretta Morgan

TC: I feel honored to see the drafts of this poem – thank you for sharing the thinking and the desire to not be thinking; how the poem seems to have begun by talking and thinking, yes, but how it also begins in the midst of an unresolvable moment (“And first, the first period of that arrest was not in a sense that I couldn’t stop thinking about it, it was that I actually felt that I couldn’t think about it, and so I felt destabilized in a way and that destabilization also made it difficult for me to think about other things.”) that has a kind of time stamp on it (the occasion of the reading). So right away in draft 1 I see a writer creating a narrative about how the thinking evolved – providing context, with the exception of the event the speaker heard about (“received the news”), the narrative gaps are filled. I’m thinking about the role of narrative to get the thinking going, to kind of force one into it – but how there is a simultaneous effect of narrative (at least I experience this all the time in my life) how the narrative gesture can anesthetize me, almost prevent me from further thinking. Does that resonate with you? How do you navigate this, generally speaking, and is this a common trajectory for you – to begin by giving your thinking a narrative frame?

SM: I don’t trust inherited narrative forms and how they prescribe expectations of work. Academic science essays, for example, operate within their own methodological progression (narrative), but also rely on the narrative that what they present should be read and evaluated in terms of truth and stability and not also sound, affect and syntax.

In terms of my own narrative-building lately, I try to operate under the intention that everything I say is 100% possible, even though I know that as text that is formally recognizable as poetry, my work often won’t be read that way. The expectations of our genre don’t demand it. But in room for a counter interior, I write “what if the room were a state in constant motion,” and I mean that. Dead ass. I believe rooms move constantly, and that we’re coerced through a matrix of narrative logics which demand we unsee that information. Enough evidence has accumulated in my body to convince me of that fact, and now I have to work backward … take the idea and its conditions apart … to make sense of it. “Sense” in all of its meanings, all of the ways in which information can register. It’s aesthetic, by which I mean it’s available to the senses.

Adrian Piper has an essay, “Talking to Myself: The Ongoing Autobiography of an Art Object,” in which she talks about her art-making process as as a constant critique of her own aesthetics. A return to the question of “why did I need to make this this way?” Her looking/moving backward resonates with me. Self-critique is something I’m trying to practice more and more. The world as we know it is ending. I think this makes self-inquiry … what is my position here and how do I exercise it? … really urgent.

TC: “even though I know that as text that is formally recognizable as poetry, my work often won’t be read that way…” Can you say more about this? I'm hearing you say (and correct me if I'm wrong) that formally recognized poetry resists speculation - is that what you mean?

SM: What I'd meant was that within poetry (regardless of form, more like, the announcement that it is poetry, whether by form or by explicit labeling), there's an implied flexibility of language and intention. Like, that perhaps I'm substituting an image for something literal. And that assumption isn't present (in the same way, at least) within non-fiction. So when I write work that uses things like line breaks, centering, fragmented sentences, readers identify it as poetry and suddenly I'm up against the assumption that I don't necessarily mean what I'm saying literally.

TC: “we’re coerced through a matrix of narrative logics which demand we unsee that information.” On a visceral and intuitive level I get this but my mind is struggling to catch up - can you help me?

SM: Sure. Lately I've been motivated by Katherine Mckittrick's work. Her study of how space materializes through the meanings we project onto it. I extend this thought very literally, as in, when I walk into a room, the space must change in response to the consequences of my specific movements and personhood. That idea isn't supported by dominant narratives (and by "narrative," I mean what we develop to organize the world and situate ourselves within it.) Assumed concepts of objectivity, ownership and linearity, among others, work together to obscure the possibility that a wall can shift depending on what occurs in relationship to it. (TC yells YES to computer screen!)

TC: “constant critique of her own aesthetics” - using what you said earlier - aesthetic as available to the senses - is this, then, a critique of what is available to her senses and/or a critique of her senses and/or a critique of how available one is to their own senses or something else?

SM: Yeah. Those are great distinctions and I think Piper's process touches all of them. What I meant was that it is a critique of what her art-making has made sensually available, which is in some ways also a questioning of her own sensibilities as an artist. I like that your question differentiates between what is present and what is available to the senses. Which I think points back to your previous question, in that there is sensory information beyond what we recognize.

TC: “The world as we know it is ending. I think this makes self-inquiry … what is my position here and how do I exercise it? … really urgent.” - how does this poetic practice - self inquiry - play out in that world that is ending - in other words, how has your poetic practice shaped/influenced your living, your daily interactions, relationships, etc.?

SM: It's made me a better listener.

TC: Is recording yourself a typical practice for you – thinking and talking about something, recording yourself talking about it, then moving onto the page?

SM: When Natalie and I first started dating, I would record the readings she couldn’t attend and send them to her. Honestly, I disliked returning to them very much. This was the only one I listened to on purpose. Part of that was because, at that time, physical presence felt integral to the experience of the text.

TC: What is your time aesthetic? How do you live time and work with it formally?

SM: My working definition of aesthetic right now is, “the way something is materialized.” What comes out and how it comes together. I was talking about this with regard to time with a group of poets the other week. Muriel Leung put it an interesting way, which I will summarize by saying that after experiencing information, the amount of time that has passed before we release it affects how and where the information has been able to metabolize in the body.

So (to ride with Muriel’s analogy), when I said time passing, I meant that perhaps the events needed be processed through other organs and muscles before it could be made into sense that was meaningful to me.

TC: When you don't know where to go next with a poem but you know the poem is not yet finished with you (or you are not yet finished with it), what do you do?

SM: I’m working on a book-length poem manuscript, Plan Upon Arrival (Selva Oscura/Three Count Pour, 2020) and I get stuck often for several weeks at a time. When this happens, it helps me to think in another language-system. Through work made by visual artists and critical theorists. Right now I’m working on a few essays and curating features that bring together critical race theory, performance theory and architectural theory to think about works by contemporary Black artists and writers. I’m also in conversation with a robotics engineer on a project addressing water use and its consequences in the Southwest. Everything I produce in those arenas comes back to pressure my book, and the perspectives I’m able to hold while I write it.

TC: “visual artists and critical theorists” - care to point us to a few folks who have your interest right now?

SM: Bebe Miller, Tina Campt, Lauren Harris. I think all of them do an excellent job of thinking about the poetics embedded in the material conditions of their fields.

TC: When, in your writing process, do you consider your reader and to what end? I think I’m asking something here about communication and its role in poetry.

SM: That’s a hard one for me to answer. I'm not sure when.

Lately I think about the range of Black women who I love and imagine them all into one room. I ask myself what I have to do to bring everyone into the conversation. It's a kind of proxy to see how many corners of myself I'm speaking from.

As a text-based artist, Saretta Morgan's work engages relationships between intimacy and organization. Recent writhing has appeared or is forthcoming in The Guardian, The Volta, Nepantla, Apogee and Best American Experimental Writing. She has designed interactive, text-based experiences for The Whitney Museum of American Art, Dia Beacon, and Tenri Cultural Institute. Saretta received a BA from Columbia University and an MFA from Pratt Institute. She is a 2016-2017 Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Workspace resident and author of the chapbook, Room for a Counter Interior (Portable Press @ Yo-Yo Labs, 2017)

TC Tolbert often identifies as a trans and genderqueer feminist, collaborator, dancer, and poet but really s/he’s just a human in love with humans doing human things. S/he is Tucson’s Poet Laureate and author of Gephyromania (Ahsahta Press 2014), 4 chapbooks, and co-editor of Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics (Nightboat Books 2013). www.tctolbert.com