In Poet's Corner, Tucson Poet Laureate TC Tolbert shows us several drafts and revisions of a poet's work, then speaks to that poet about the writing process.

Poet's Corner with Sam Ace

Author's note: A version of this poem “There in the dusky blue” was published originally in Original Plumbing and started with a prompt (I honestly don’t remember what the prompt was) from jj hastain.

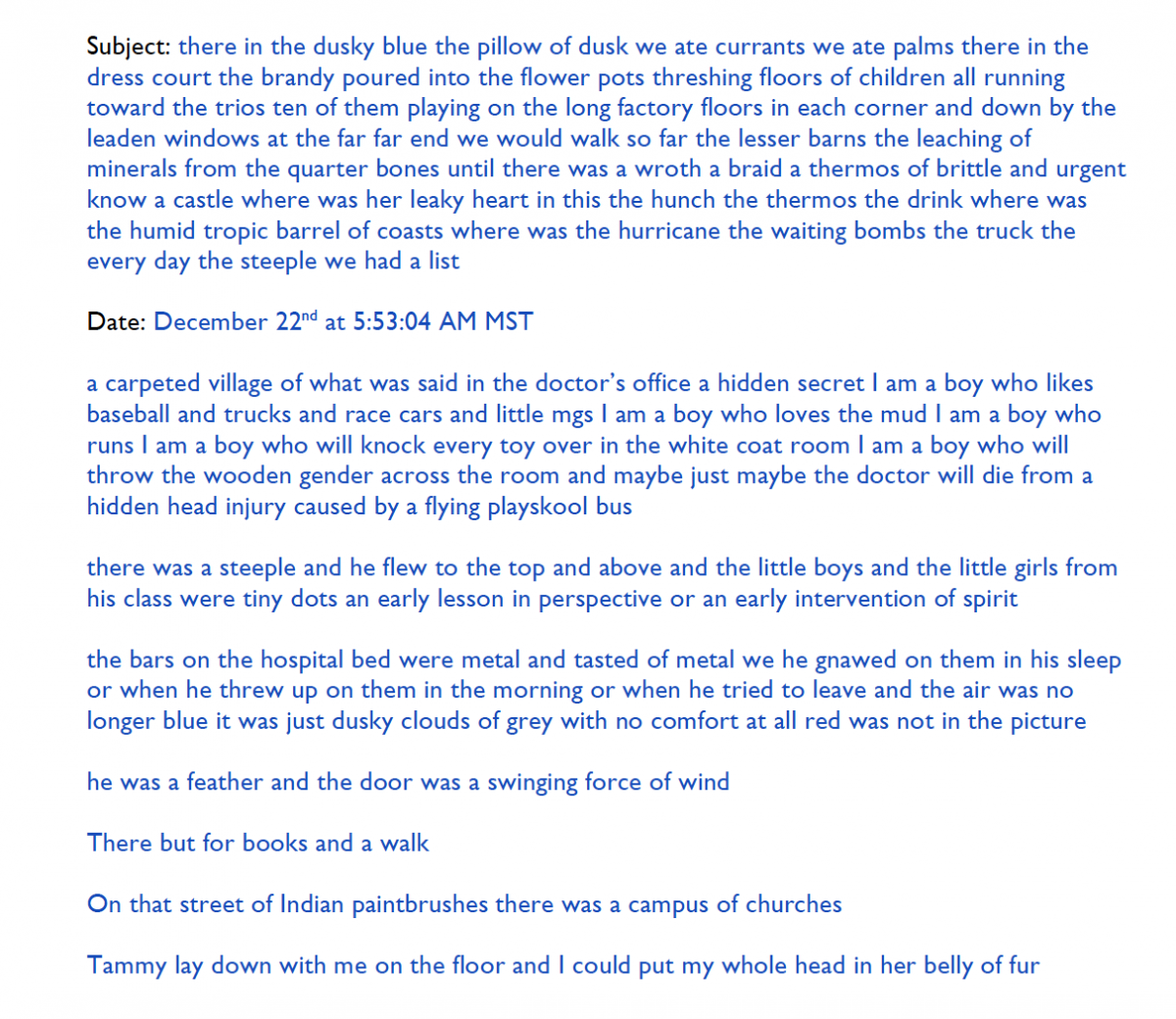

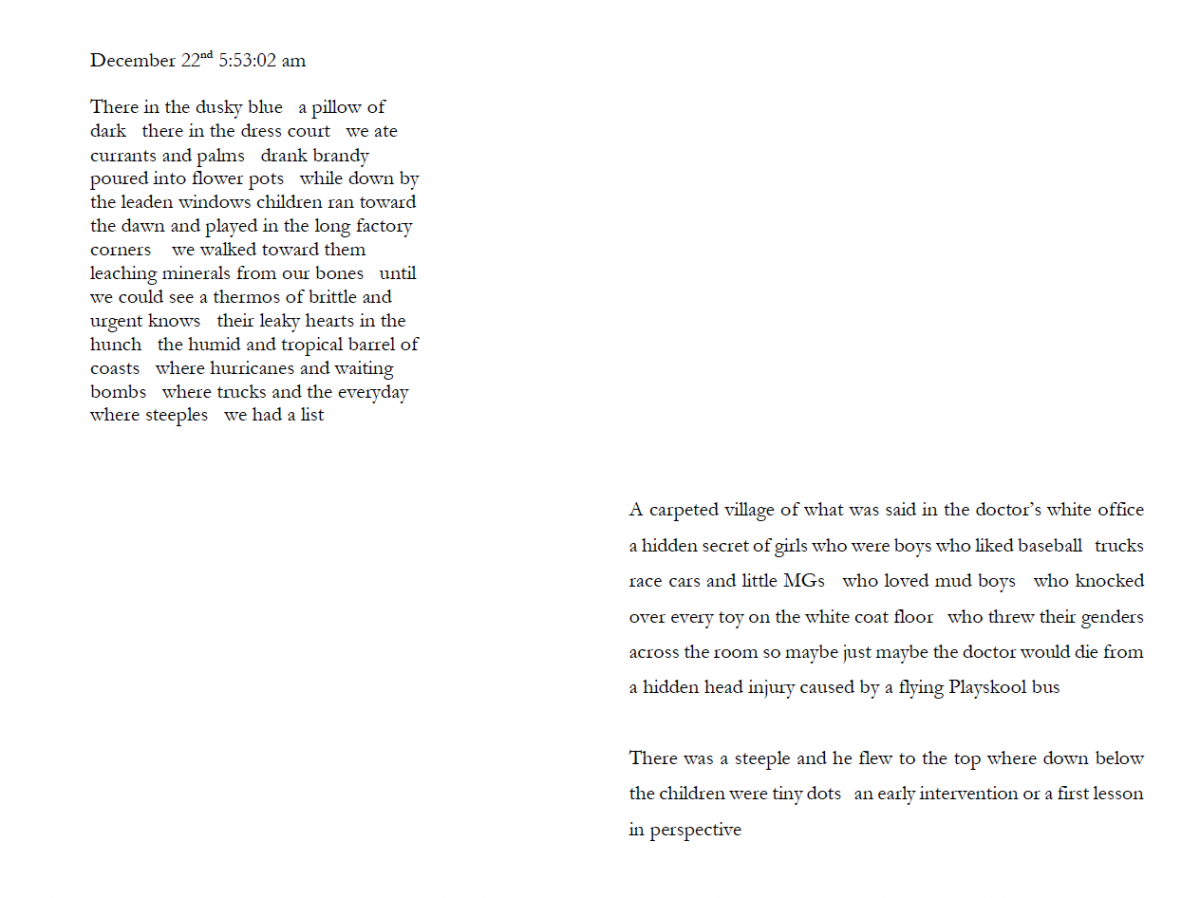

Draft 1

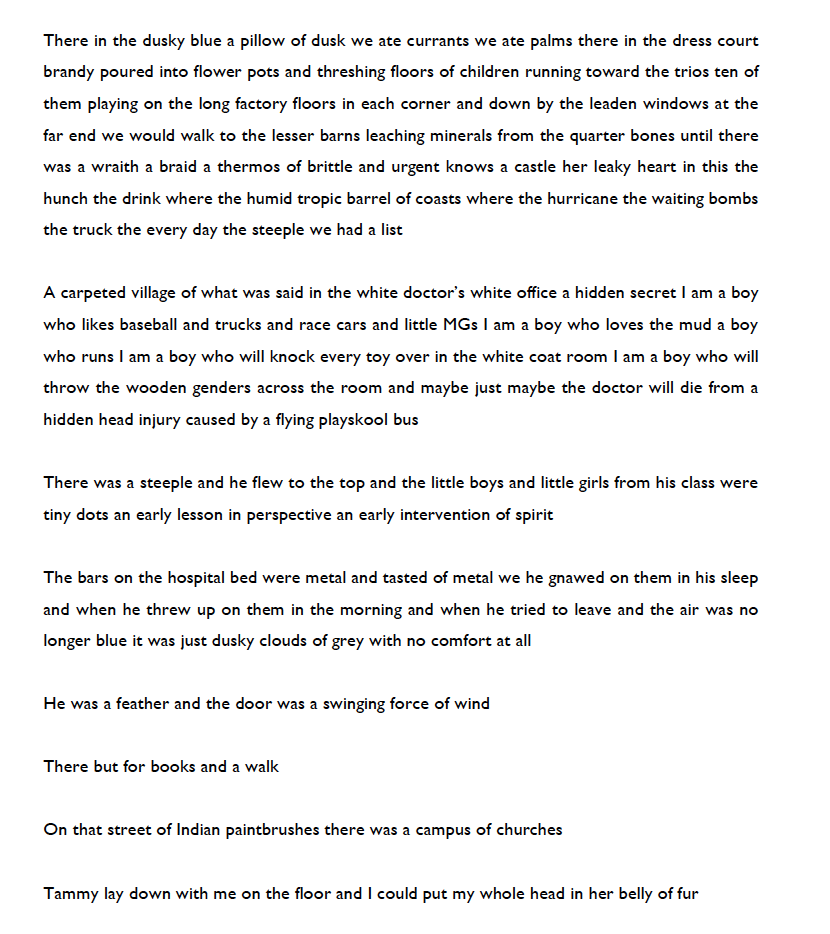

Draft 2

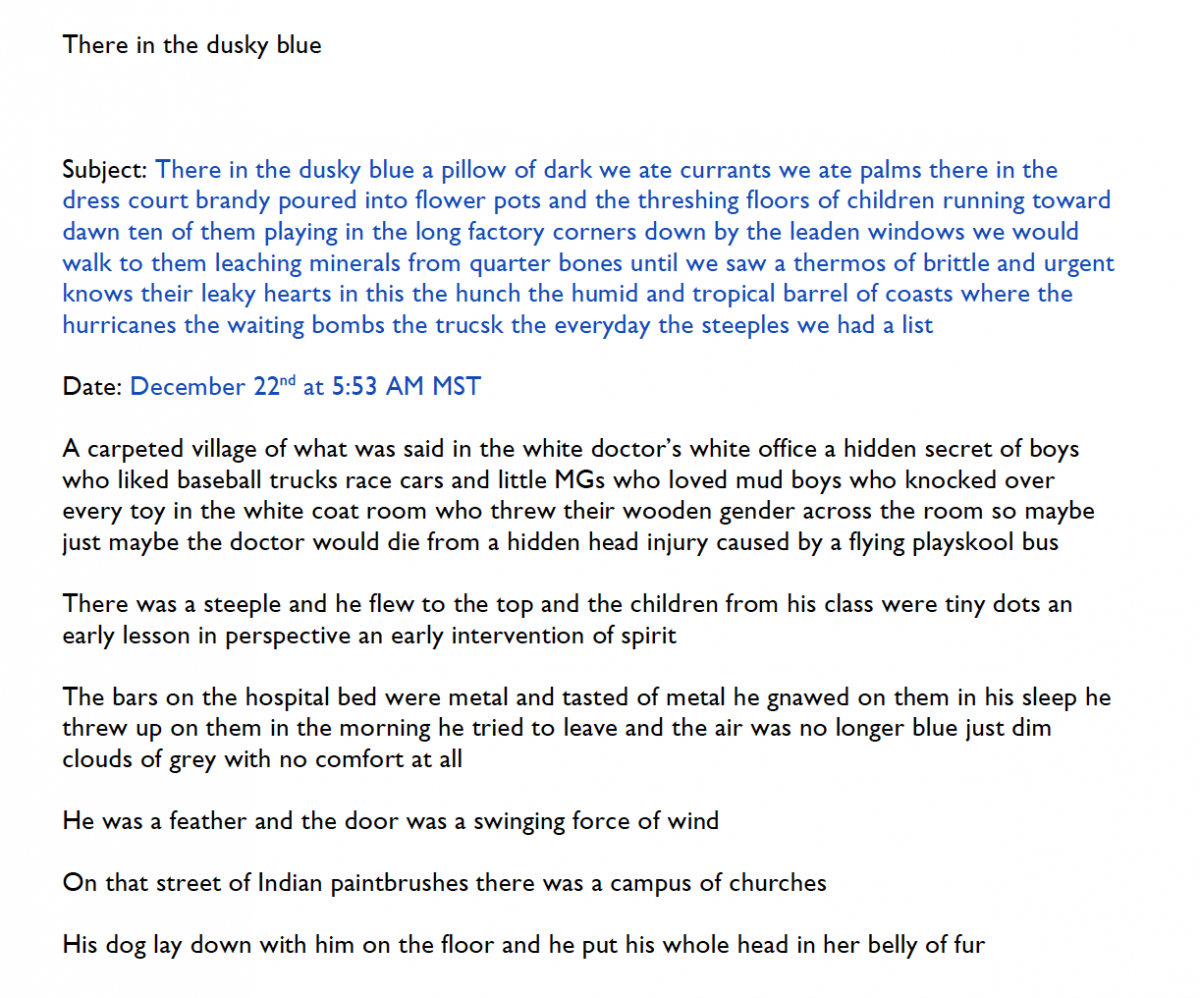

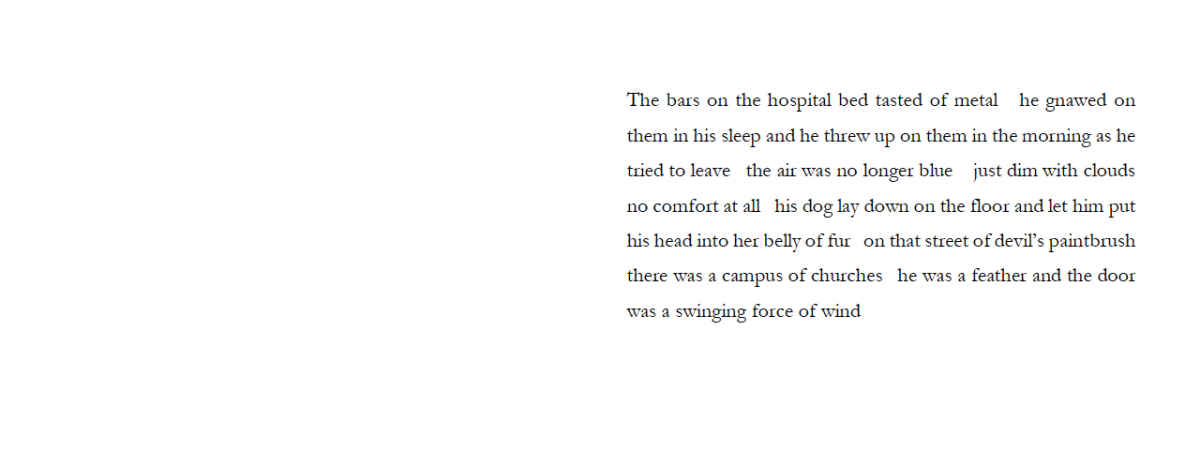

Draft 3

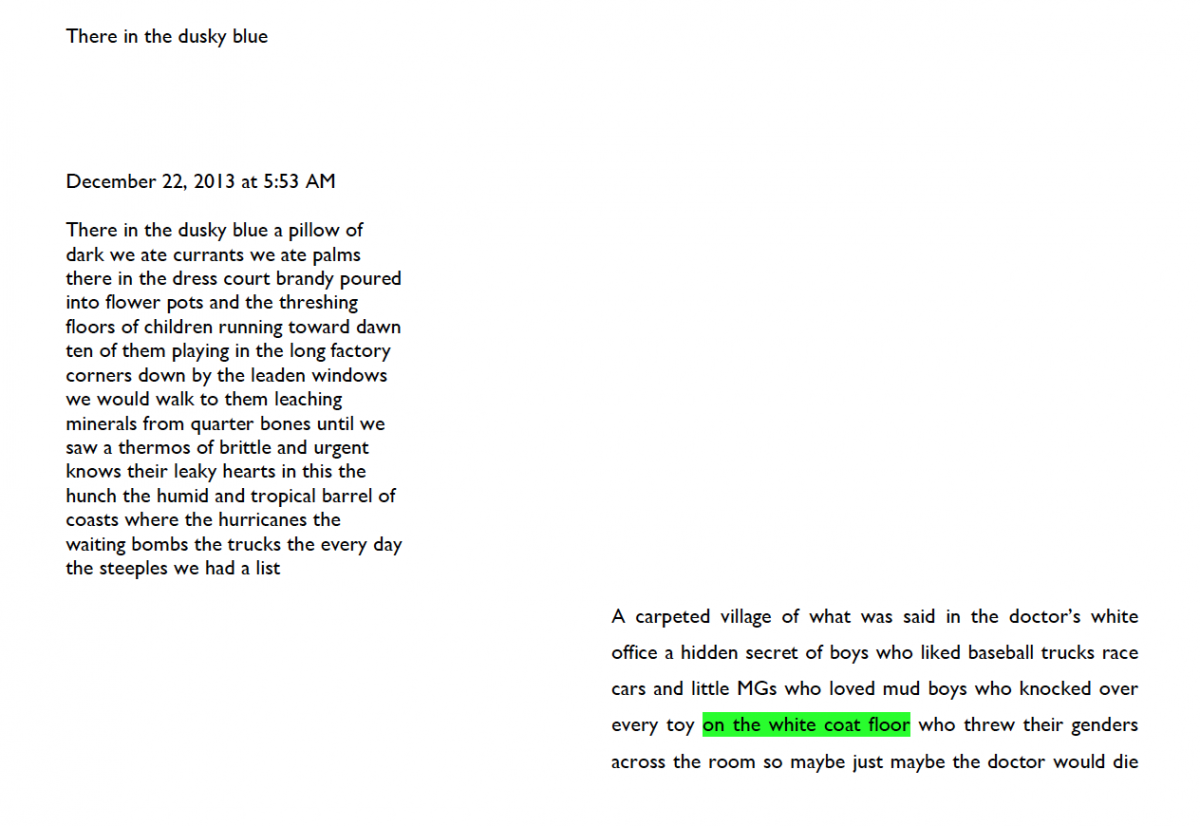

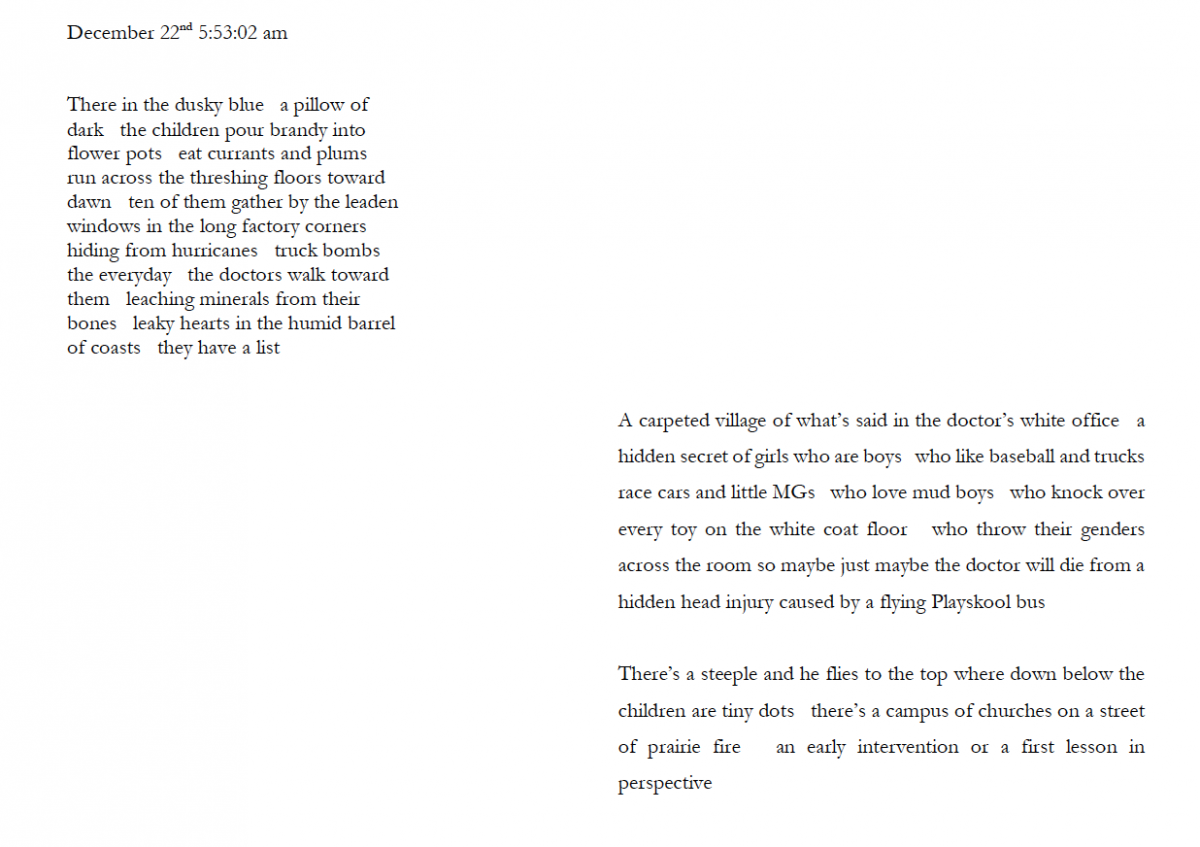

Draft 4

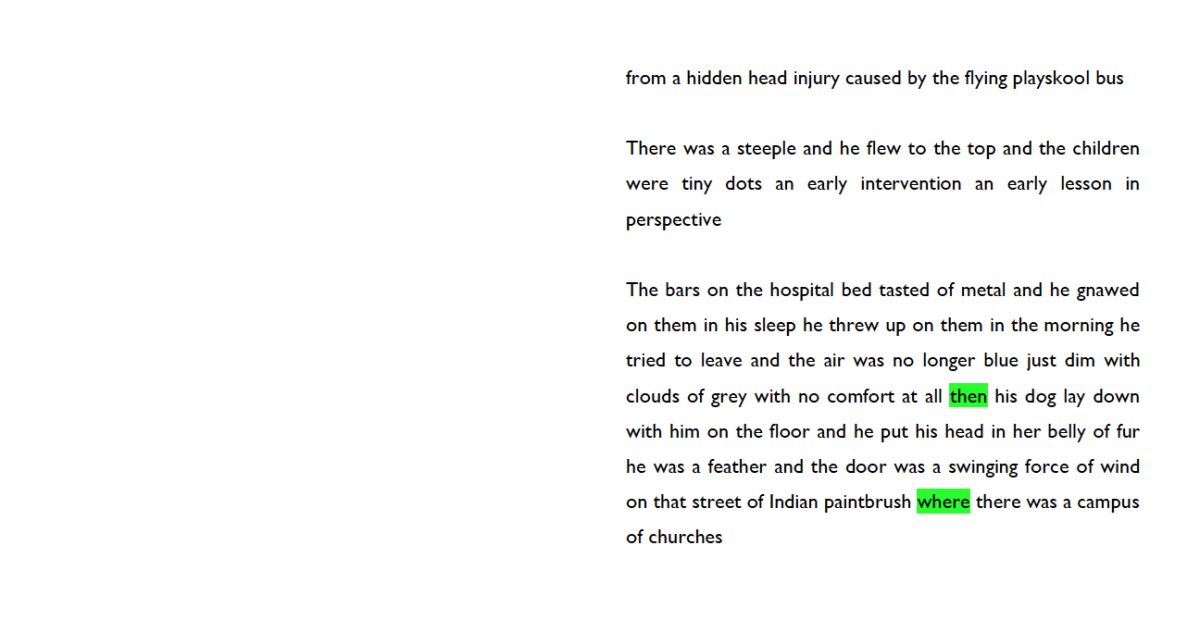

Draft 5

Final Draft

***

Questions and Answers for Poet’s Corner

TC Tolbert with Sam Ace

TC Tolbert: Hey Sam! First, I gotta admit, before getting your drafts, I didn’t know how much I would enjoy reading 6 drafts of a poem – seeing it evolve, sometimes only slightly, and absolutely reveling in the repetition of whole phrases and segments across the drafts. This reminded me of listening to your live performances/experiences/readings, your work with improvisation, looping, a sound board, and other technology. Can you talk to me about how your live performances inform your work on the page (generally) and if/how this particular poem was revised due to working with it in front of an audience?

Sam Ace: TC! First, thank you for the opportunity to talk about this poem, to go back, and to see my process over time. It’s something I rarely do in such depth, and because of your inquiry, I think it’s something I want and need to do more often. So I’m grateful! When your email came about this project, I had just been working on the poem I eventually sent to you. It was first published a couple of years ago in Original Plumbing, the trans-masculine journal edited by Amos Mac and Rocco Kayiatos, in an issue (#16) devoted to trans writers and literature. When re-examining the piece for a possible new publication, as well as its inclusion in my forthcoming book, I thought, wait, there’s more I still want to do with this poem. So I started to rework it from the version that had been published, but not much further back than that. Although the revision process was very fresh, I really hadn’t gone back to the beginnings of the piece until I heard from you. I do often rework poems up to the moment they are published, and as you can see, sometimes after they are published. I’m not sure they are ever finished. Perhaps just put away until they pop back into my consciousness again.

You asked about my recent sound pieces and if they have informed my work on the page. Yes. Absolutely. And vice-versa as well. The sound pieces come directly out of how my work has evolved over the last several years. In early versions of poems (“There in the dusky blue” is a good example of this) I would often start with a ‘Subject’ that would be followed by an improvisation on the subject. This was literal and first came about when I began an email correspondence with another poet that involved sending prompts back and forth to each other. During this exchange I made up a form for myself.

The form started out as a mistake. Here’s some background to that ‘mistake-turned-into-form’:

1) I often write new raw work first thing in the morning with my eyes closed, typing in the dark. This helps me hold onto that state between sleep and being awake, where the channels of my consciousness are more open and fluid.

2) I compose email on a Mac laptop in the Apple mail app.

At some point early in that correspondence, when I thought I was typing in the body of an email, I found (when I finally opened my eyes) that I had actually written a fair amount of text in the subject line. Something about that immediately appealed to me, I’m not sure exactly what. Perhaps it was the linearity, the hiddenness, the on-goingness. So I just kept doing it, using the form of the application as an armature. Maybe I liked the structure of filling out a ‘form’ as a way to hold language. As it developed, the form entailed writing the entire first part of the poem in the subject line – a line that, if it went on long enough, I couldn’t see the beginning of. As a rule, the subject could have no punctuation or spaces - it just had to spool out until it was done. When I came to a stopping point, I would copy and paste the ‘subject’ into the body of the email. I could now see a block of text, instead of what first appeared as only a one-way linear scroll. From there, I would improvise, sometimes as a meditation on the subject, sometimes through a repetition of the original phrases, changing the language, sometimes entirely, sometimes just slightly. I became interested in how small alterations of language and rhythm could form a more dimensional meaning, like looking at the different interiors or sides of an object or a house. I seemed to be questioning my own revision process - often wanting to leave in much of what might, in other circumstances, be edited out. I also associated this impulse with music, with chorus, with call and response, with the form of the fugue. As you indicated in your question, over the last few years, I’ve been creating sound versions of poems, to include, in performance and in recordings, those places where language becomes sound, and sound becomes language. I’m still exploring this territory!

“There in the dusky blue” also turned out to be more of a meditation, a vehicle for the way old memories will arise in poems, where strands of those memories begin to associate with emotions and events, some fictional, some actual, some dream-like, to weave with the present into a kind of narrative. In subsequent revisions of this poem, I strove to clarify that narrative, and to make sure the language, the flow of sound and rhythm, sat well in my ear. Ultimately ‘sitting well in my ear’ comes down to intuition, to saying and singing out loud, over and over, until somehow I’m satisfied. At least for that moment.

TC: Speaking of audience – at what point do you become aware of audience in these drafts? I know there is a lot of talk about getting the audience out of your head – especially for writers who feel shut down by the critical voices that seem to be on a constant loop (but what do I know about that?! J ). However, I think audience (both real and imagined) can be very useful for creation. What are your thoughts about audience? Who do you imagine your audience to be (when alone in a room writing) and how does that differ from being in front of an actual audience? Can you see points in these drafts where you are turning toward the audience in some way – meeting their presumed needs (and if so, what are they)?

SA: I was thinking about audience when looking for a piece to send to Original Plumbing. Because of this particular publication, I wanted something that spoke more directly to transness. Looking through work in various stages of ‘finish’, I found this poem. When I was writing it, the poem became a meditation on childhood alienation, specifically a trans-related alienation from the culture-at-large. I was thinking about my own childhood experience with doctors, psychologists, the measurers, the data gatherers, and the keepers of gendered power. The images in the first part came to me in one of those early morning subject scrolls, part dream. I have often written into images of captivity, a feeling that was very strong in my childhood. The following ‘answer’ in the second half, the ‘body’ of the poem, speaks to anger, escape, and the self-soothing that can arise out of alienation. I also returned to the image of out-of-body (dissociative) events, experiences I had fairly often as a child and beyond. All of the subsequent drafts became an attempt to get closer to those experiences, while holding onto the associative leaps and the physicality of the language, which I hope in turn embodies those experiences for the reader. Maybe that’s why I never feel like a poem is ‘done.’ I always want to get closer, to dig deeper into the dirt.

Was I thinking about judgmental voices when I wrote that first draft? No, at least I don’t remember that I was. It’s not that I don’t have those voices. The beauty of writing first thing in the morning in the dark, with my eyes closed, is that those voices are at their weakest. On the other hand, I do think about children who have had, or might still be having, similar experiences to mine, who don’t have language yet to speak. I do think of teenagers and adults who might recognize themselves somewhere in a poem. Are these individuals part of my audience? I hope so.

TC: One of the reasons I wanted to run this interview series is to pull back the curtain, so to speak, on the revision process. There’s plenty of talk about how revision takes a long time and/or can be an extraordinarily involved process, but we rarely (if ever) get to see that process – especially in accomplished poets such as yourself. What has changed in your revision practices over the years (generally speaking)? And could you put this poem and how you approached its revision in a larger context of your work? Also, would you chart this poem’s progression – what were some of the questions you began this poem with, did you answer any of those questions (and if so, how), and what questions did you end with?

SA: I think I’ve answered some of these questions in my answers above. In the second draft of the poem, I put the two parts together into one long prose poem. When I did that, I found that I missed the back and forth of the two sections, so I put back the ‘subject’ label, the date and time, and separated the two sections on the page. In many of the poems in this form, some of which were published, I added in salutations, a Dear L (for my former name, Linda), and a Dear S (for Sam) – to emphasize parts of me that were talking to each other. In final revisions I took out the “subject” label and the salutations, as it ultimately seemed awkward and unnecessary, especially when reading the poems out loud. The salutations also became somewhat meaningless, as the two parts of the poems seemed more like different sides of the same voice instead of two separate voices (I could say the same for Linda and Sam!). However, I did decide to leave in the date and time because I liked the way they rhythmically marked the poems, like a stamp.

In recent years, I think I’ve worked more to unrevise rather than to revise. By that I mean, as raw as first drafts, ideas, notes, phrases can be, there’s often an essential, physical energy in them that can be easily erased through refinement. Sometimes that raw energy is just a hint of a more powerful rhythm and meaning that needs to be further excavated. In the actual making, the act of writing for me is as much a physical, embodied act as it is a mental conjuring. The subsequent result (the poem) needs to hold that physicality in the air and in space, needs to cast a spell, beyond the page. That is my best hope for poems, one I fear I continuously fail to achieve.

TC: B/c I'm hoping for Poet's Corner to function as a teaching tool, I'm wondering if you could share a suggestion for approaching revision?

SA: Looking back at my process, and the evolution of this poem in particular, I’d say that time has played the greatest role. Something happens if I can step away and let the language marinate. The act of writing is very intimate for me, sometimes so intimate, I lose the ability to clearly hear what is happening. Although in very rare occasions a poem will just emerge very close to finished, most often I find I need distance to hear what the poem is trying to say, and to fully understand its rhythms and sound sense. In other words, my understanding of both the content and the physical body of the poem gets clearer if I can put it away for a while, then come back, say it out loud, sing it, call it out into the air.

TC: And/or: when you don't know where to go next with a poem but you know the poem is not yet finished with you (or you are not yet finished with it), what do you do?

SA: Go back to what I did in the beginning. Close my eyes in the dark to open a channel, put my hands on the keyboard, and begin to write.

TC: Is 6 drafts a typical number of drafts for you? How long (in hours, days, weeks, etc) did you work on each draft and how long did it take from start to finish for this poem?

SA: I think there were many more than 6 drafts! I have been writing this poem over years, TC. It will finally come out next year in a monograph of poems. Maybe that will be the end of it. But maybe not.

TC: For years I’ve watched you carry a tiny notebook and pen and take notes during poetry readings. Talk to me about those notes – what are you listening for and how do you use the notes later? At what point do you transition from handwriting to technology and is there ever a point when you return to handwriting during the drafting process?

SA: Yes, I do often bring a little notebook to readings. When I was doing this most actively, I thought of writing during readings as a way to engage with what I was hearing. Although I am sometimes taking notes by writing down phrases or thoughts that call out to me, more often I’m doing something different. I’m writing actively with the person who is performing, trying not to think too hard about what’s coming through my hands onto the page. I imagine that I am in a duet and/or an improvisation, even though the performer has no idea I’m doing that work, or anything about the residue that’s fallen into the journal. I have tried to turn what I’ve called these “Listenings” into something, but so far they haven’t really formed into anything much. Maybe because what ends up in the journals is only one side of my imagined duet, and the other speaker is missing. The act itself feels intimate though, and gives me a greater, more embodied understanding of what a poet is doing, more than being a passive listener/gatherer of their work.

Handwriting is another question. I know that for many writers, the physicality of holding and writing with a pen or pencil is a direct connection to their body. For me however, that physicality comes most naturally through my fingers on a keyboard. I’ve written elsewhere about studying the piano at a very young age. I learned to type in middle school, and since then have found that the writing flows more naturally for me on a keyboard than through handwriting. My whole body moves when I’m composing, as if each keystroke has the possibility of expression - volume, timbre, color, attack, tone, phrasing – connected to every other key, chord, phrase. I hope some of that physical embodiment remains visible on the page and in the sound of the language. I’m always looking for it there.

Part of me feels completely raw and exposed in revealing so much by showing the naked mewlings that are the beginnings of a poem. The mess of it all. But as a teacher and student of poetry, it’s something I wish more of us would do – to show each other and our students that work does not fall fully formed from some perfect poet mind, whatever that is. I guess for me the work always evolves as an intimate and vulnerable process, an exploration, and an invention. I want to make sure the energy of the initial ‘mess’ stays present in the end. So thank you again for asking!

Samuel Ace is a trans and genderqueer poet and sound artist, and the author of several books, most recently Our Weather Our Sea, forthcoming in 2019 from Black Radish Books. Also in 2019, the Belladonna* Collective, as part of their Germinal Texts series, will reissue his first two books, Normal Sex and Home in three days. Don’t wash. Widely published, he is the recipient of the Astraea Lesbian Writers and Firecracker Alternative Book awards, as well as a two-time finalist for both the Lambda Literary Award and the National Poetry Series. Recent work can be found in Poetry, Vinyl, Posit, PEN America, Gramma, Fence, and Best American Experimental Poetry 2016, and many other journals and anthologies. He currently teaches at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, MA.

TC Tolbert often identifies as a trans and genderqueer feminist, collaborator, dancer, and poet but really s/he’s just a human in love with humans doing human things. S/he is Tucson’s Poet Laureate and author of Gephyromania (Ahsahta Press 2014), 4 chapbooks, and co-editor of Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics (Nightboat Books 2013). www.tctolbert.com