In Poet's Corner, Tucson Poet Laureate TC Tolbert shows us several drafts and revisions of a poet's work, then speaks to that poet about the writing process.

Poet's Corner with Rosemarie Dombrowski

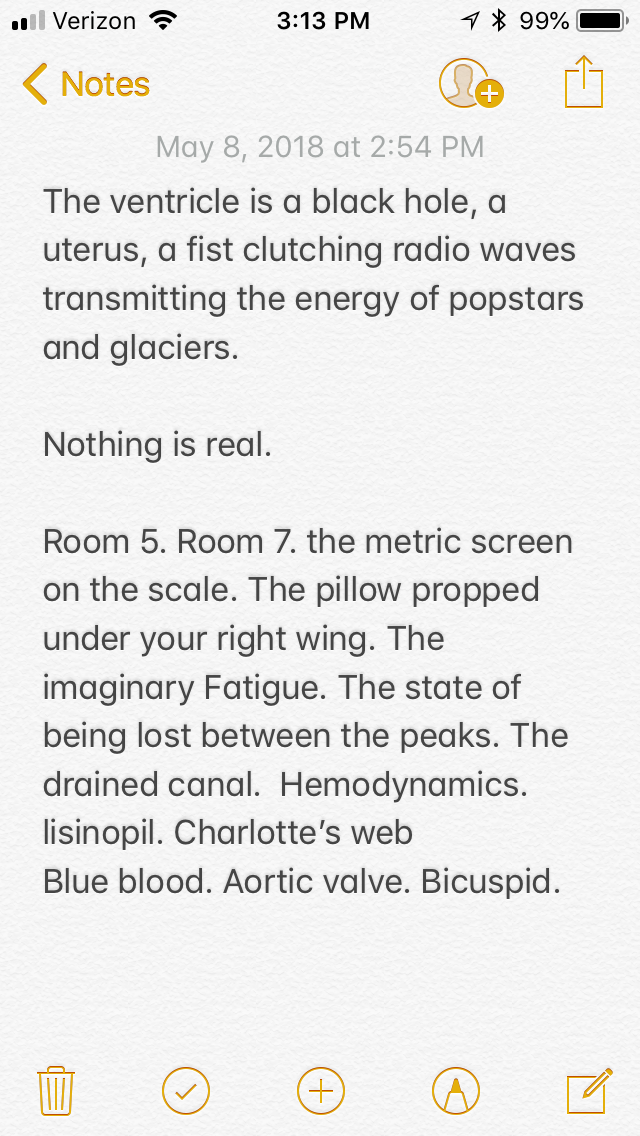

Notes

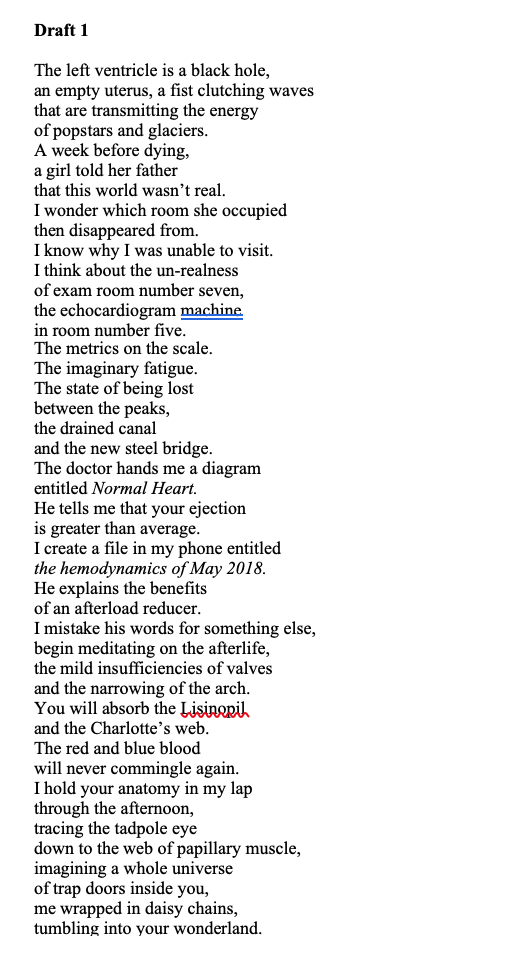

Draft 1

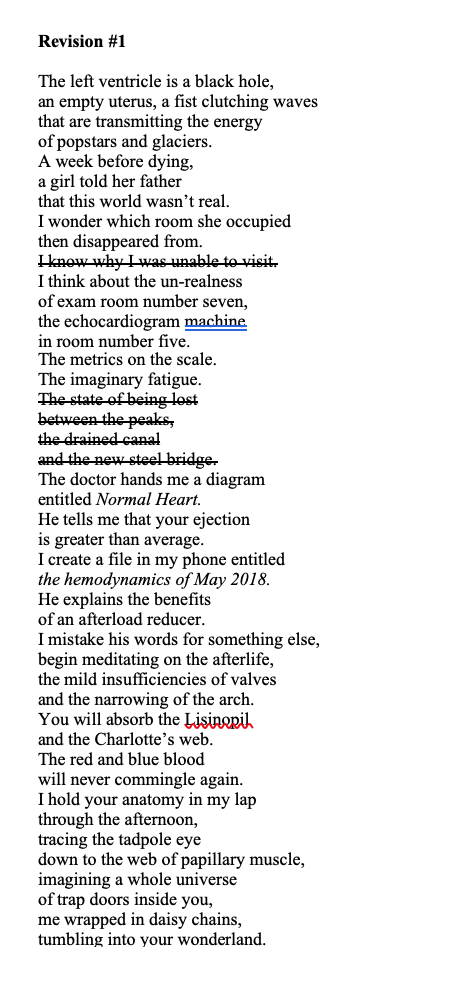

Draft 2

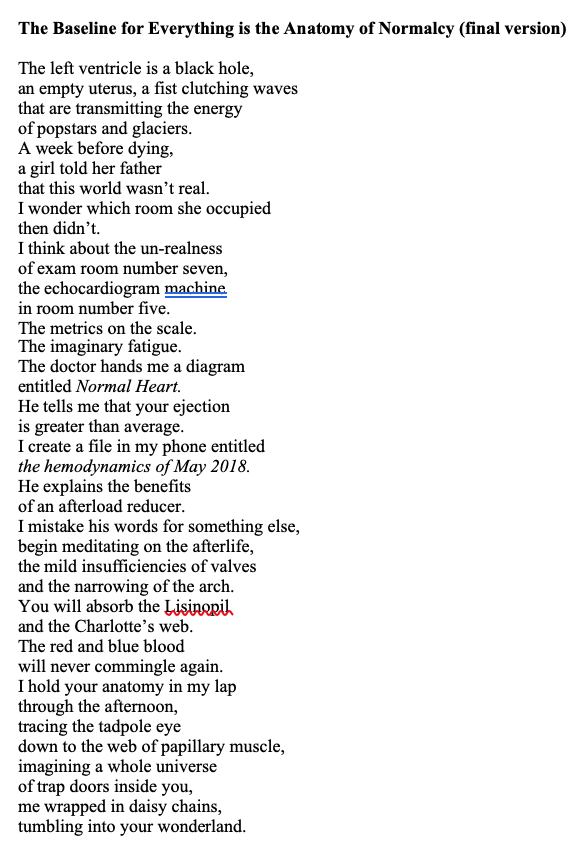

Final Draft

Questions and Answers for Poet’s Corner

TC Tolbert with Rosemarie Dombrowski

TC: I’m so excited that we are having this conversation. When I heard you read in Phoenix about 6 months ago, you mentioned working on a poem by speaking notes into your phone while driving and your first image here is of phone notes. I’m interested in the difference between phone notes and notebook notes – I sort of assume that phone notes open up something for you that notebook/long hand writing does not (since none of the drafts here involve long hand writing) – is this true? Talk to me about your use of phone notes – not just in terms of convenience but what it allows (encourages?) in the creation of the poem.

RD: I’m a fast thinker and speaker, a quick processor of visual and auditory information. Maybe because of that, my memory is shit. Dictation (into my phone) allows me to play to my strengths, to record things as quickly as I see/hear them and almost simultaneously begin processing them. In something of a found poetry kind of way, dictation also allows me to borrow from the environment—street signs, billboards, highways markers, public conversations, radio banter, etc.

Once I’m back home, I send the notes to myself—which are typically a list of observations, maybe a few phrases—and start crafting more of a narrative from there. Sometimes the recreation is faithful to the event, sometimes less so. And sometimes it’s less narrative than this one.

Overall, phone dictation is a method that I use when I’m stricken by a scene or scenery, something I might transform into observational poetry. The bulk of my work isn’t generated in this way.

TC: Are you an “early adopter” – did you start incorporating technology like phone notes as soon as it became available – are there other forms of technology you use when writing (other than, say, a laptop and a basic word doc)?

RD: Well, it’s ironic that I’ve only had a phone for two years (LOL), but I’ve had a laptop for 20 or so years, and yes, I almost immediately transitioned over to word docs. I rarely use notebooks anymore. I rarely handwrite. My hands don’t move deftly or quickly enough. I’m typically a writer-deleter—I think this is going to answer one of your next questions as well—meaning I delete almost as much as I type in the first iteration, so I’m not sure where version 1 ends and 2 begins…or where version 2 ends and 3 begins. This assignment was particularly difficult for me for that reason!

That said, when my son needed emergency surgery this past July (2018), I asked the nurses for paper and a pen so that I could write while he was in the OR. Oddly enough, I ended up writing a series of one-line sentences, almost four pages worth, and those were later translated into a four-section poem with a similar cadence.

That said, I’ve written on post-it notes and masking tape, old receipts and my hand. When I’m desperate enough, I’ll use any writing implement and/or surface, but I’m a laptop poet at my core!

TC: The first line of phone notes is a metaphoric statement (that I read as an investigation, I think, b/c I always read metaphors as an attempt to know something, and I find a lot of pleasure in the tension between the declarative sentence form (“x is y”) and the reaching/almost accuracy of metaphoric thinking (knowing that, in fact, a ventricle is not a black hole). In my understanding, the phone notes seem to offer two distinct readings/possibilities/options:

- uterus is another metaphoric possibility for ventricle, as is fist clutching radio waves – in other words, we stay with the ventricle and keep investigating what it can be OR

- the ventricle investigation is abandoned (or jumped from) and now the speaker is thinking about the uterus and comparing it to a fist

Am I close? Further, my question/curiosity lies in how that gets resolved in draft 1 and stays consistent with option 1 across subsequent drafts. Did you consider option 2 and/or what are the other ways of reading stanza one in phone notes that I may be missing? Maybe this is actually a question about what you are looking at and working with when you go back to develop your phone notes. How important is your original intention (and/or original question) in subsequent drafts?

RD: I think I was thinking more of a fist inside a uterus, i.e. an in utero scenario. But my intention was to convey that the uterus is a ventricle and vice versa—I wanted to collapse/conflate the two “chambers” because of they ways in which they both sustain life. And of course, there’s the gestational and familial bond that I’m establishing—he is from my uterus, and metaphorically speaking, he’s from my heart as well.

But to get to the crux of your question, I’m ok with letting go of the original intention, especially if the central question or exploratory trajectory of the poem remains the same. I think I tend to abandon intention when I know that my original intention isn’t being conveyed clearly.

TC: I’m also really struck by the phone notes and how different it is (and now I’m treating “phone notes” as its own poem) in tone, imagistic concision, associative leaps, lack of connector language, length, shape, and embedded narrative from “Draft 1” and “The Baseline for Everything is the Anatomy of Normalcy.” I love them both (phone notes and final) but for very different reasons.

Can you talk to me about loss and gain in the act of writing and revising (generally) and in this poem’s development (specifically)? What do you feel you lost in going from “phone notes” to “Draft 1” to “The Baseline…” and what do you feel you (or perhaps I should say, the poem) (maybe I should say, both of you) gained?

RD: I tend more toward the expository, especially in final drafts of poem, maybe because I’m as much of a flash memoirist as I am a poet. Or maybe because as a mother/ethnographer of the culture of non-verbal Autism, I know that I have to constantly negotiate between what will be intuitively understood by the reader, what can potentially be understood by the reader, and what the reader will likely never understand. Those three outcomes aren’t necessarily at odds with one another, and though I refuse to sacrifice sound or lyricality for the sake of explication, I’m always considering their interaction and balance (or lack thereof), especially when I’m getting close to a final draft.

For me, the “gain” in Baseline is my realization of what the scene (poem) requires in terms of the balance between transparency and mystery…so what it gains for me is balance. I suppose that’s fitting given the analogy of Autism to a puzzle or mystery in need of solving. It’s like I’m sleuthing my way through the tangle of the knowable and the unknowable until I find the sweet spot, and I always hope that the spot where I land will be inviting enough for a diverse audience to join me/us (my son and me).

TC: Maybe this is a place to talk about why you write poems/what you come to poetry for/what you hope your poems will do?

RD: For the majority of my writing life, I’ve written as a means of survival. My entire grad school career (9 years) was shaped by an unexpected pregnancy, an infant with life-threatening congenital heart defects, and a diagnosis of Autism shortly after his second birthday. My son has never spoken, and it took us fifteen years to find our footing—CBD for him, talk-therapy for me. All those years of white-knuckle mothering, of being a single twenty-something graduate student with a self-injurious child who couldn’t speak…fuck, I felt like every day was a near-death experience. But the classroom was my sanctuary (I was a TA all nine years), and the page was something like an altar, a place where I could lay my offerings, my loathsome prayers, my faltering faith in everything.

I guess my greatest hope for my poems is that they’re recognized as cultural narratives, or that they serve as a voice of disability culture/the culture of nonverbal Autism…and simultaneously represent the culture of caregivers.

TC: Finally, I'm hoping for Poet's Corner to function as a teaching tool and companion for fellow writers. I know you teach writing, as well. Could you share a suggestion and/or a lesson for approaching revision?

RD: I love-love-love a good workshop, and I always try go get my hands on my students’ syntax and mechanics form the outset. Granted, maintaining the integrity of their voice in the process is a delicate dance, but I wish more CW instructors were truly hands-on. Again, I believe I’m only there to facilitate the development of the style and voice that they’re already developing, so revision isn’t about remaking or bulldozing, but I believe that you, the instructor, have to get in there and work the words like clay. It’s a magical experience, and the closeness it fosters between you and your writers is profound, and before you know it, there’s a trust between you, and eventually a kind of symbiosis of sound, and then the only thing left to kill are those endings, the ones that try to tie everything up via a sense of not-so-profound finality or explication. I typically cut the last 2-3 lines of everyone’s poem, so I guess what I’m saying is that you work the words like clay, but you’ve also got to pinch off the excess.

Appointed in December of 2016, Rosemarie Dombrowski is the inaugural Poet Laureate of Phoenix, AZ. She is also the founder of rinky dink press, the co-founder and host of the Phoenix Poetry Series, and the curator and host of First Friday Poetry on Roosevelt Row, an event that takes place amidst the monthly art-walk in the heart of Downtown Phoenix.

Her collections include The Book of Emergencies (Five Oaks Press, 2014), which was the recipient of a 2016 Human Relations Indie Book Award for Poetry, The Philosophy of Unclean Things (Finishing Line Press, 2017), and the The Cleavage Planes of Southwest Minerals [A Love Story], winner of the 2017 Split Rock Review chapbook competition. She is the 2017 recipient of the Carrie McCray Memorial Literary Award in nonfiction, an Arts Hero Award, and a Fellowship from the Lincoln Center for Applied Ethics for her Community Poetry Gardens project.

She was recently named the winner of Silver Needle Press’s Flash Fiction Contest (October 2018) and the runner-up in the Force Majeure Flash Contest (2018). Additionally, she has been nominated for five Pushcart awards and was named a finalist for the Pangea Poetry Prize (2015), the Winston-Salem Writers contest (nonfiction, 2017), and The River Styx Microfiction Contest (2018).

She is a Senior Lecturer at Arizona State University’s Downtown Phoenix campus where she is the co-founder and faculty editor of the student and community writing journal, Write On, Downtown, and where she teaches courses on the poetics of street art, women’s literature, and creative ethnography.

TC Tolbert often identifies as a trans and genderqueer feminist, collaborator, dancer, and poet but really s/he’s just a human in love with humans doing human things. S/he is Tucson’s Poet Laureate and author of Gephyromania (Ahsahta Press 2014), 4 chapbooks, and co-editor of Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics (Nightboat Books 2013). www.tctolbert.com