In Poet's Corner, Tucson Poet Laureate TC Tolbert shows us several drafts and revisions of a poet's work, then speaks to that poet about the writing process.

Poet's Corner with Felicia Zamora

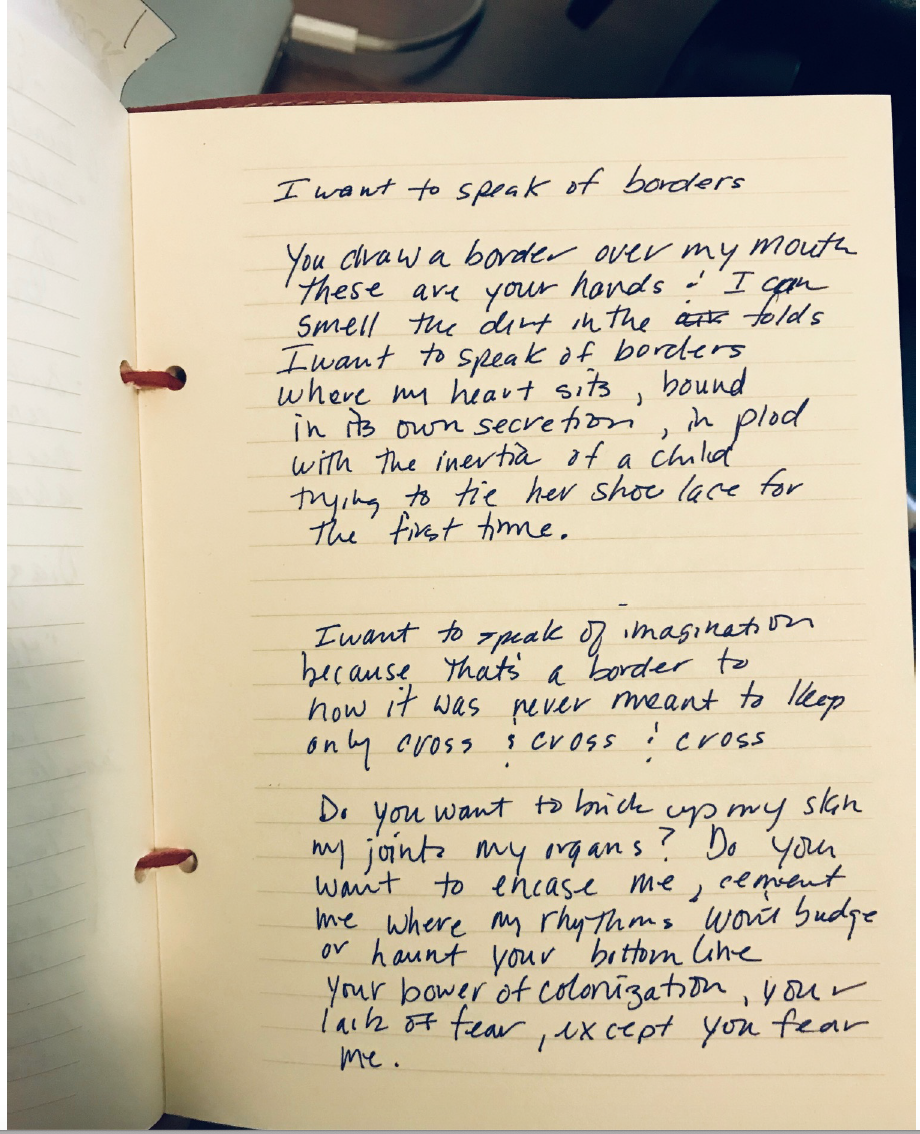

Draft 1

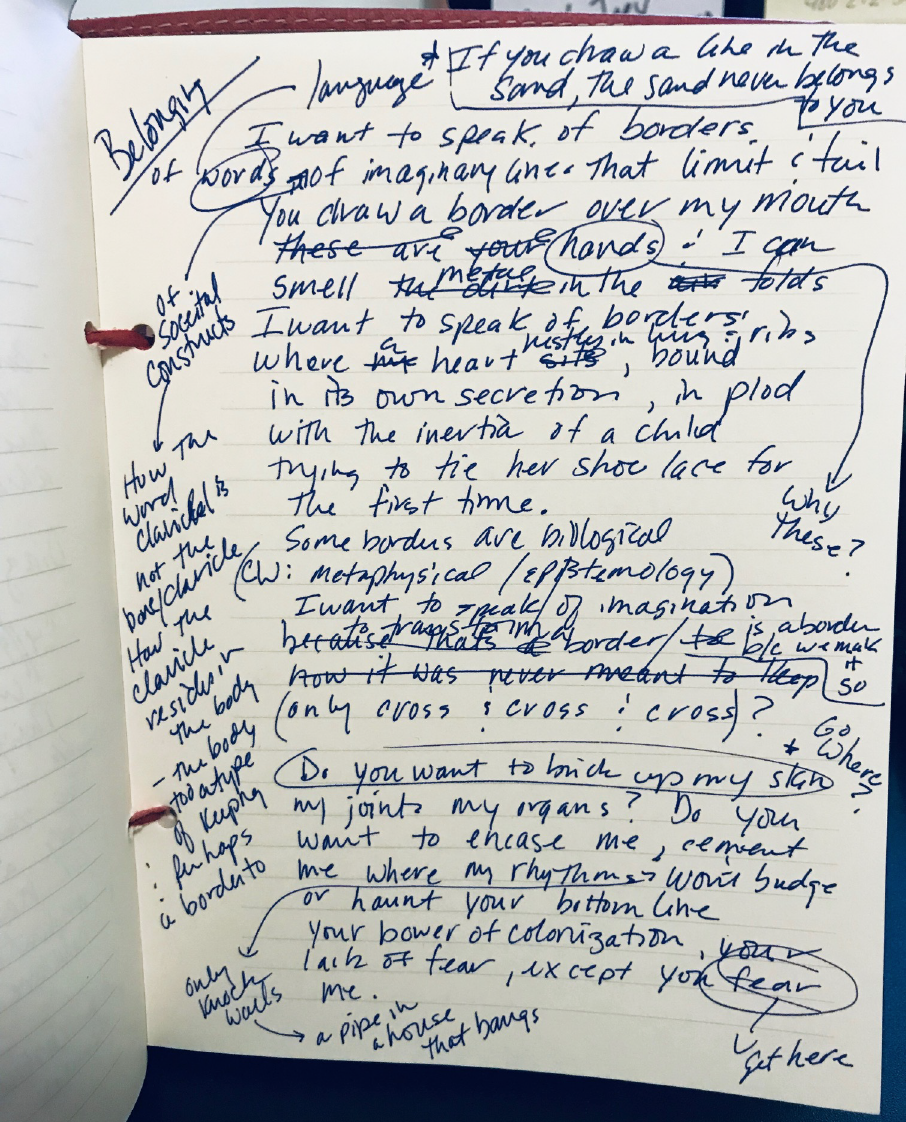

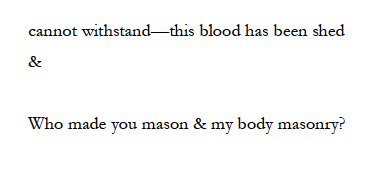

Draft 2

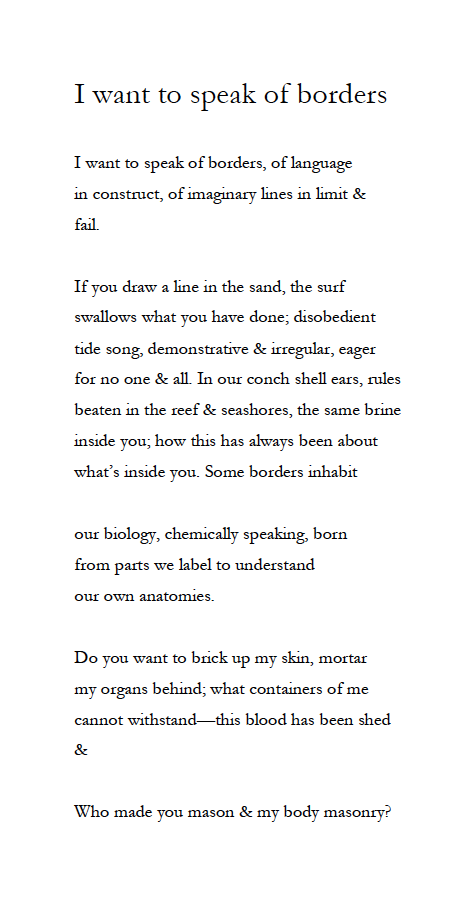

Draft 3

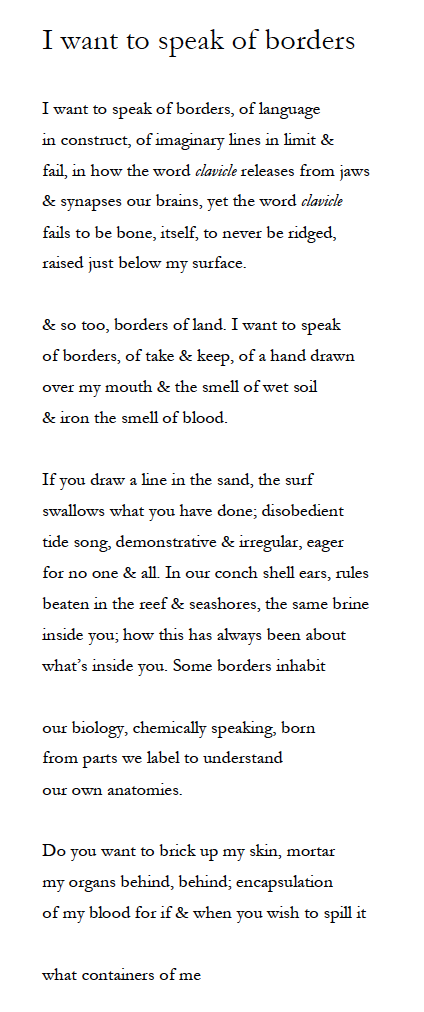

Draft 4

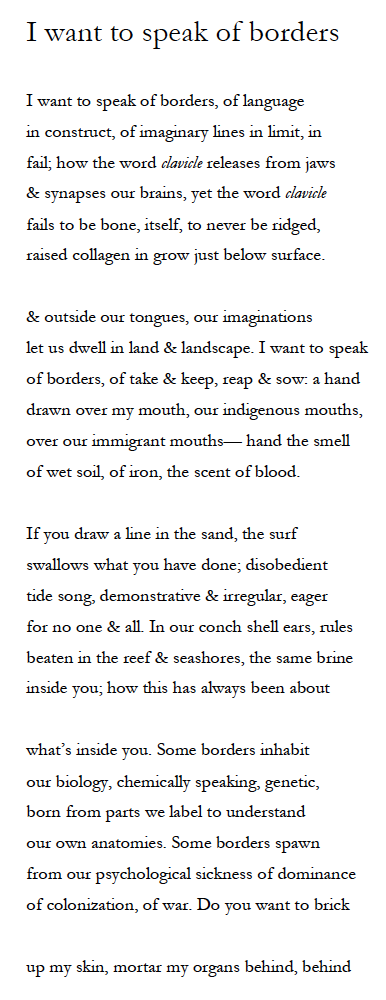

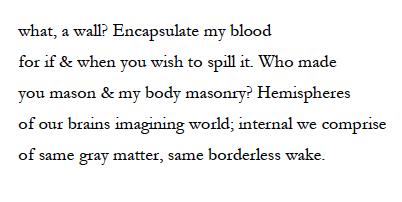

Final Draft

Questions and Answers for Poet’s Corner

TC Tolbert with Felicia Zamora

TC: Thank you so much for participating in Poet’s Corner with me! When I first asked you to be involved, you said: “I do have one strange thing about my drafts, though…I actually revise over them and do not save them. I tend to trust my own revising processes and do not allow myself to linger in the what the poem ‘was’ but what it has become. Therefore, for your request, I may need to write something new between now and Oct. 15 and actually keep the drafts that lead up to the final version.” So, to begin, I’m dying to know how this drafting process went and what this solidified and/or challenged about your usual process. (I’ll likely ask further/clarifying questions about this once you’ve answered b/c contrasting the two feels really rich. So feel free to take this one and run with it.)

FZ: This activity was completely unnatural, awkward, even. It enlightened me; it allowed me to reveal my own process to myself, one which I thought I knew, but hadn’t really dwelled in before. My focus has been on the artistic process, to trust my instincts and to cut and revise in almost one simultaneous breath. In this activity, I slowed down and documented the moments of language and ideas that would normally find their way to the page, delete, rewrite, delete, rewrite, and mold, mold, mold, until a line, image, or voice felt natural. I learned revision is ingrained in my process, without hesitation and with little loyalty to original ideas or language explored on the page. Usually, I don’t have an investment in what’s on the page until I find what feels natural to the moment, kind of like smelling and caressing an avocado in search of the one that feels ready. I am vicious about finding that thing, that harmony I’m searching for. I don’t know what that harmony is, though, until it reveals itself to me.

TC: The title of the poem stays consistent throughout the process and I’m curious about sitting down with an intention for the poem (“I want to speak of borders”) and the way language can be such a slippery fish and begin to move the poem away from those original intentions. I mean, in saying “I want to speak of” anything, there is a tension of what one wants to speak of and what one ends up speaking of. When do you find yourself surrendering intention and when do you hold on tight?

FZ: Actually, the first line written in the first draft was not the title...it was just the phrase my brain was mulling over and over, then suddenly I wrote it and a space came after it. You know, this is one of the first times I’ve written a poem by starting with what ended as the title. Perhaps, the activity, itself, required that I have some sort of life-line, buoy if you will, to keep me grounded due to the unnatural recreation (and perhaps creation, really) of my internal artistic development of the poem. This is also one of the few times that I revised over the course of more than a few days. I left this process, came back, and then left it again, and came back. Rarely, do I do this. Usually, it’s intense, held-up-in-a-room writing until the poem feels harmonious in some way. The intention you speak of, kept me woven into the expression. Perhaps, the poem is only an “attempt”, though, because it became intention driven. This definitely happens. My clever mind, more often than not, hinders the art’s evolution. Typically, I push back on intention when it impedes the process too much. Maybe this was simply a different type of process for me and the art?

TC: Can you/do you have interest in tracking that surrender and/or grip in this poem?

If you had not been keeping drafts (i.e. if you had been following your usual process), how do you imagine this poem would have developed differently?

FZ: Hard to speculate. I don’t think it would look anything like the poem you see here. I do think the idea “I want to speak of borders” would be present— in what form, only the process knows.

TC: In the first handwritten draft, the “you”/address is central – whereas in the final draft, the need and desire of the “I” is foregrounded and the “you” doesn’t enter until 3rd stanza and finally the poem focuses on the “we.” Because I get to see the way the poem develops, I experience this shift as a wrestling away of the you’s power through the drafting process. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this shift in emphasis – how conscious it was, your visceral experience of it, etc.

FZ: Yeah, I felt the wrestle for sure...glad you did too. The art mimics the artist’s experience. I chalk this one up to a few things: my struggle with the activity and my personal struggle with the topic. Being Mexican, the physical and metaphysical manifestations of borders to the body, cognitions, and society are always both an I and we experience wrapped into one. The turn toward questioning language, leaning on punctuation, the use of second person are all techniques I pull closer toward me in the process when I write about complex and personal topics that resonate my core. The you changes as well. The you in stanza three is slightly different than the you in stanza five. The use of second person complicates voice where, at times, reader and writer are one, and other times, the you is separated by the first person. This fluidity and complication surface a lot in my poetry. So much of what I consider is about this larger we, this colliding of I, you, and we, into a collective that must move together through space and time to enact change. The poem, like society at this moment, is unable to converge in a truly satisfying way. The poem’s end feels like a plea, a cry for understanding.

TC: Maybe this is a place to talk about why you write poems/what you come to poetry for/what you hope your poems will do?

FZ: Ultimately, I write because I must. I’m drawn to the art for the sake of the art. I also believe in art as activism; when anyone chooses to write poetry, that individual is already choosing, in some dimensions, to be resistant...resistant to prose, to being outlined too easily, to a process that culls and tears, but also reshapes and evolves a person. I’ve felt resistant to superimposed restrictions on me and humanity my entire life; those narratives that chunk and bite at people, the ones that piss on equity and social justice, the oppressive narratives, I’ve been resistant to these since I can remember. This poetry, this art, allows me to create a micro-world that questions everything about the world. When I was young, I was kicked out of confirmation class for asking too many questions and arguing with the pastor. I’m proud of that. What I hope my poems will do...maybe my deepest desire is that another individual will be empowered to use their voice, and that they will connect with one word, line, stanza, image, voice, moment of my poetry and not feel alone. Poetry and other forms of art also have the power to pull back the curtain, hold a mirror up to us, expose our raw actions, the entire spectrum of our actions as humans, the horrid to the tender-ist, and let us see ourselves reflected back in honesty.

TC: At what point is an audience present for you in writing (in this piece and in your work, in general, b/c I imagine that knowing you were writing toward a future conversation (this one!) might have made the audience more present from the beginning but I don’t know…)?

FZ: Most of the time I am writing for my own mind, but with knowing that art has impact. The art isn’t dictated by audience; however, I also understand that words have deep capacity to elevate or gash, and even in the artistic process, each word in the poem is considered over and over again. Sometimes this consideration is about how a word talks to the words around it, to the line, to the stanza, to the poem’s experience, but also how language has the ability to create wounds. I go to the page ready to pay attention; every word, punctuation mark, image, metaphor, nuance in grammar, line, risk, point of enjambment, all needs to be attended to. Maybe my audience is no one? Or everyone? It doesn’t really matter, as long as the diligence is there on my part...ready for whomever falls into it.

TC: I really enjoyed seeing the clavicle and meditation on language in specific terms initially arrive as a note in the margin in draft 2 and then disappear in draft 3 and then make a center stage stand in drafts 4 and 5. In general, I notice the drafts moving more and more toward specifics in image, figures of speech, and description. Can you talk about how you think and work through the kinds of language you use in poems – abstract, concrete, figurative, etc.?

FZ: In my natural process, I think I am always searching for balance of concrete details and images with the experience of the poem. In this exercise, I found myself writing down thoughts that I may have immediately erased before. I think this allowed for the abstract to linger longer in conceptualization. My obsession with the body, this home in which we physically experience the world in tandem with the mind, brings me back to our biological components and the words in which we describe our physicality; how we speak ourselves into being, fascinates me; how we use and abuse language. On a cellular, synaptic level, so much happens inside us, as we simply go about our day. I think this internal work, this internal mystery, is not unlike the artistic process of selecting language in a poem: it’s maybe 20% skill and 80% magic.

TC: Finally, I'm hoping for Poet's Corner to function as a teaching tool and companion for fellow writers. Could you share a suggestion for approaching revision?

FZ: Trust yourself. Trust that you know your art better than anyone. Don’t spend your life revising. Get the art to a place that it feels ready, however that looks for you and your relationship to the page, and then let it live; let the poem be the art it was meant to be. Poets are obsessed with the minutia. We could spend our whole lives revising. Don’t. Trust yourself. Attend to the language in a necessary and important way, but don’t let revision block you from continuing to produce art. Trust yourself.

Felicia Zamora is the author of the books Of Form & Gather, winner of the 2016 Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize (University of Notre Dame Press 2017), & in Open, Marvel (Parlor Press 2018), and Instrument of Gaps (Slope Editions 2018). Of Form & Gather was listed as one of the “9 Outstanding Latino Books Recently Published by Independent and University Presses” by NBC News. She won the 2015 Tomaž Šalamun Prize from Verse, authored two chapbooks, and was the 2017 Poet Laureate for Fort Collins, CO. Her published works may be found or forthcoming in Alaska Quarterly Review, Crazyhorse, Denver Quarterly, Hotel Amerika, Indiana Review, jubilat, Lana Turner, North American Review, OmniVerse, Pleiades, Poetry Daily, Poetry Northwest, Prairie Schooner, Sugar House Review, The Cincinnati Review, The Georgia Review, The Nation, TriQuarterly Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Verse Daily, Witness Magazine, West Branch, and others. She is the Associate Poetry Editor for the Colorado Review, holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Colorado State University, and is the Education Programs Manager for the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing at Arizona State University. She lives in Phoenix, AZ with her partner Chris and their two dogs.

TC Tolbert often identifies as a trans and genderqueer feminist, collaborator, dancer, and poet but really s/he’s just a human in love with humans doing human things. S/he is Tucson’s Poet Laureate and author of Gephyromania (Ahsahta Press 2014), 4 chapbooks, and co-editor of Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics (Nightboat Books 2013). www.tctolbert.com