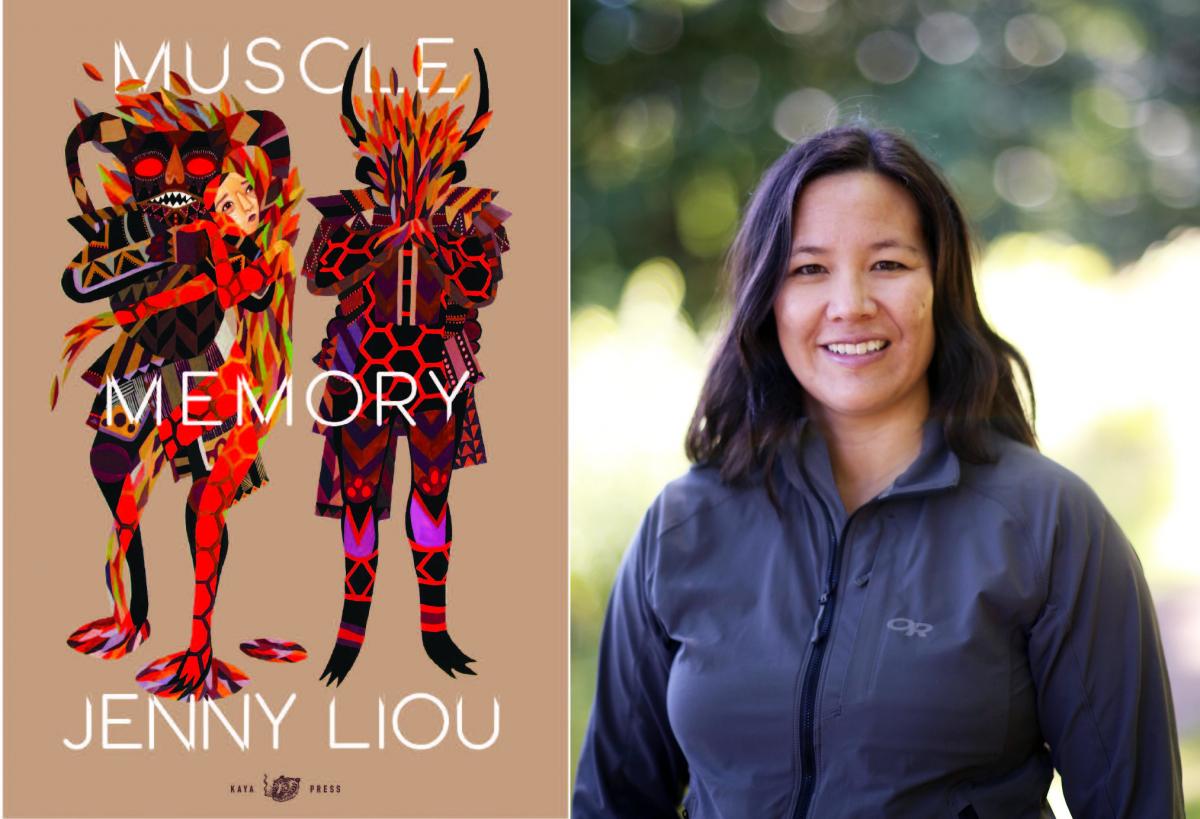

Below, you'll find a conversation between Jenny Liou & Raisa Tolchinsky. Their wide-ranging dialogue puts in conversation their works, including Liou's recent book from Kaya Press, Muscle Memory.

Jenny Liou is the author of Muscle Memory (Kaya Press). She is an English professor at Pierce College and a retired professional cage fighter. She lives and writes in Tacoma, Washington.

Raisa Tolchinsky writes about love, grief, and the wisdom of the body. She is the recipient of the Henfield Prize for Fiction and a 2x Pushcart Prize nominee in poetry. Raisa earned her MFA in poetry from the University of Virginia and her B.A. from Bowdoin College. She has previously lived and worked in Chicago, New York, Italy, and Iceland and is trained as an amateur boxer. Currently, Raisa is the George Bennett Writer-in-Residence at Phillips Exeter Academy.

***

Jenny Liou: We both reference Juvenal— you in an epigraph, me in the title of a poem. I’m curious about the spectres of the Roman gladiator in your work (and mine)— how is that something we aspire towards? How do we work against it?

Raisa Tolchinsky: I’m so glad you brought this up. I’m thinking about the legacy of disgust-distrust towards women/femme fighters– wanting those words to be as inclusive as possible. Women have fought for so long, in both physical and emotional and spiritual ways, and there have always been men who’ve hated it. I was so angry reading his rant about women gladiators– it made me ask, what about women fighters was so offensive, and still is, to many people?

My poems are golden shovels, using Juvenal’s line, “how can women be decent, sticking their head in helmets, denying the sex they were born with?” as text to work within, around. It feels like a conversation back and forth across time.

My question was and is, how do we work within the language that binds us, as if it was a ring itself, while breaking it open? Jenny, now I’m curious, how do you locate yourself within that question? And curious, too, about your choices to include other literary references– Li Po, Wang Wei, Adorno, Stanley Cavell, just to name a few. Did your relationship to any of these figures change by including them in your book?

JL: Mens sana in corpore sano (a sound mind in a sound body) the line I borrow from Juvenal, is a dictum that captures the Roman sentiment that the mind and body ought to be trained in tandem– being a scholar, a poet, and a warrior were sort of one and the same, and not some sort of accident or aberration. Juvenal might be a placeholder for me, however. I’m more drawn to Roman orators like Cicero and Quintialian who ceaselessly explore embodied language, though part of how they explore it is by insisting on being un-excerptable– the sense of any phrase dependent on the context of the next.

You ask about language that binds us, boxing rings that bind us, and the ways we find to break them open… none of the poems in Muscle Memory call out Sappho by name, but let’s go back to the pre-Socratic Greeks for a moment here. Sappho’s fragments certainly inform my project, and Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho is probably an unbidden ghost in my project as well. What does it mean to lose your body, whether it’s a body of writing, whether it’s your fighter’s form declining from its peak, or any of us moving through life and then out of it? The part of your question about breaking things open strikes me as a boxer’s question– the clinches and ties get boring and breaking the combatants apart makes things interesting again. From a grappler’s perspective, I guess I crave connection, arm-drags, over-under grips. As an MMA fighter, I’m usually in a cage and not a ring, and it’s something I want to use, not escape from. I love setting up sweeps and armbars off of the cage, or if things get ugly, getting my back against it and using it to inch my way back up to my feet. I crave the chain link cage. The literary references that find their way into my book might seem very different from each other, but I those authors all explore, in their various ways, the same questions that I’m trying to ask: what happens when we lean into violence and loss, when we are participants in them, when we let ourselves feel them in our muscles and bones, instead of letting them vanish into ghosts and ideas.

We both have some poems that are dense little blocks, and some that breathe a bit more on the page. What, in the context of this work, does the poetic line mean to you? How does it stand in metaphor to the body? To the ring?

RT: When I think about “poetic boxing”--

- A word is a punch

- A series of punches is a line (or a combination)

- A series of lines (combinations) is a round

- Therefore, a stanza is a round

- A slip / weave / duck is a caesura or enjambment

- A series of stanzas (rounds) is a boxing match

- The ring is the page, bounded by four “ropes” (its edges)

- The poem contains multiple bodies, often at odds

I must constantly be rehearsing, revising, and watching the “bodies” of my poem as they move around the page. In each individual poem, I must ask: what / who is in conflict? Where is the tension? Is it between the text and subtext? Between lyric and narrative?

In boxing, often there is a “counterpunch” — what lines set other lines up? Can one line “negate” another?

Charles Olson’s essay “Projective Verse,” has been a crucial text for me when thinking about the poetics of boxing, even though as far as I know, Olson was not a boxer. Olson states, “the HEAD, by way of the EAR, to the SYLLABLE the HEART, by way of the BREATH, to the LINE.”

I might revise this for my own poems to say-

the HAND, by way of the EAR, to the WORD

the HEART by way of the BREATH, to the line

the LINE, by way of the punch combination, to the STANZA.

For me, in a successful poem, unlike a boxing match, perhaps there is not a clear winner— just a feeling of startled awe.

I’m thinking now of your line, “the language I know best is the one I don’t speak…” What does this mean for you in the context of this book? Reading, it felt like learning a new language, one where fishes and mountains and pomegranates and pinatas are located within the body, instead of outside it.

JL: One of the valences of that line is that I grew up hearing Chinese spoken in the home– I’ve never learned to speak or listen fluently– but because of that, I relied upon all of the other little nuances of how we language– posture, expressions, cadence, tone– so although I was entirely attuned to my family’s dynamics and their histories, this was a knowledge that did not necessarily have words. Living across a language gap in this way probably inflected my sense of what a language is, and what it is for, to begin with. It’s probably what set me up to understand boxing as a language with grammar and syntax, with cycles and seasons, with dialects. And the same goes for jiu jitsu, and MMA, or fly fishing, or gardening. One of my goals for Muscle Memory was for it to feel at once plain spoken and strange, probably because that’s how human bodies seem to me as well… my own, my lover’s, my opponent’s...

What you write about watching the bodies of your poems move around the page is so interesting to me, and makes so much sense when I consider the space, and the tensions, and dynamism of your poems. My first thought when I read your manuscript was that we were talking about some of the exact same things in almost opposite ways, and now I keep coming back to thinking about whether we could say that you write like a boxer and I write like a grappler. I don’t think there’s that same kind of movement, or that kind of tension, in my poems as there is in yours. Maybe my poems operate in those moments when a clinch or throw or tie makes two bodies operate as one, the moment when things move in dense synchrony. There is no separation or conflict between them and so all of that strangeness and conflict becomes internalized.

Let’s talk more about coaches. They’re problematic figures in both of our projects. I think for me, the concept of coach ends up substantially overlapping with the concepts of model minority acculturation and both of these tropes become uncomfortably resonant with the grooming that precedes abuse. When I first read your book, your figuration of Coach leapt off the page. What does the concept of Coach encompass for you?

RT: I’m thinking about your poem “24 Fitness,” “this need to make somebody need you until you learn to follow wherever they lead or lead you.” And also your poem about the men you fight being careful with your hair. Both those moments stunned me, because they captured the mix of tenderness and difficulty I often encountered with men in the gym, and coaches in particular.

I began to write my manuscript because I was trying to figure out my relationship to one coach in particular, who was a mentor turned difficult lover, who I came to find out, much later, had many different relationships with women in his gym. I was 21, he was at least ten years older. I thought about the absurdity of wanting to box to be stronger and more within myself, and by the end of my time training, feeling entrenched in a sort of toxic obsession. I think of him as one of my greatest teachers– he taught me how to box and probably more importantly, how to walk away, how to quit.

When I first moved to New York, I spent so much time in his gym, probably almost as much as in my own apartment. When I left, it felt like losing a family. Sometimes it felt like a cult.

In my time in gyms, I was surrounded by some of the most powerful women I’ve ever met, but it also felt like coaches were the ones in control, instructing us and timing us and telling us what to do. I like the word ‘marionette’ a lot. On the worst days, I felt like a puppet.

JL: It seems that the relationship you describe with your coach probably resonates with most women who do combat sports. That simple wish: “I wanted silk robes/ a coach by my side,/for a crowd to cheer my/name.” It galled me to see the men I trained with have this, and to feel like that kind of intimacy between a female athlete and male coach was impossible, unless it came with other forms of intimacy as well.

I want to loop back to our conversation about literary references as well. Am I correct in layering Dante onto the canto structure of your book? Because I’ve got this whole thing going on in my mind about Virgil steering Dante through the underworld, and what this story turns into when the Dante figure is a woman, and the shade of Virgil is a coach.

RT: I love that! Each of my cantos in the second section of the manuscript closely follows the 33 Cantos in Inferno. I like to think of the arc of the section as, in the beginning, the boxer/ Dante thinks her Virgil is Coach, but it turns out, the boxer is both Dante AND Virgil, leading her own self through hell. One of my mentors, Lisa Russ Spaar, read that in my work, and it feels so accurate, this idea of encountering the Virgil/ trust-worthy teacher within. In La Commedia, there is a sad, beautiful moment where Virgil leaves Dante at the end of Purgatorio. It seems like one marker of a great teacher is knowing when to leave the student to follow their own ‘inner teacher.’ That was an experience I’ve never had with a boxing coach, because the set-up was to always have someone telling me what to do. I’m still in the process of being my own coach, of trusting myself (beyond the shadow of a doubt) to be my own authority figure.

One poem that really stayed with me was “Beer Belly,” where you write about how you fight only when you’re unhappy, “when I’m happy, I’m a hedonist who couldn’t fight to save my life.” I thought immediately of this mythology of writing– of only being able to write in the midst of distress or grief. What is the relationship between writing and joy for you?

JL: Phillip Larkin’s poems taught me how to write, by which I suppose I mean that deprivation has always driven my writing just as it’s driven the way that I fight. But I don’t think this means that I (or anyone else, for that matter) needs to be in the midst of some giant hyperbolic grief in order for it to drive our writing– even the best parts of life are eroded by currents of sorrow. Perhaps paradoxically, even if for me, both writing and fighting are driven by distress, in the broad sweep of things, both writing and fighting serve as sanctuaries and bring me great joy.

RT: Another question I have is about the somatic knowledge of family, violence, ancestry– your title of the book is brilliant because it speaks to all of these, not just the repetition of physical movements. How did the definition of “muscle memory” change for you? Were there any body memories you encountered that you weren’t expecting?

JL: Early versions of Muscle Memory contained more poems about romantic relationships souring and turning violent–I guess that’s where my logical mind took this project. But the book didn’t feel finished, and I kept trying to steel myself to the task of writing the poems that would complete it. I kept asking my editor for little bits of additional time to finish revising the manuscript ,but I instead found myself writing poems about my parents working their five acres and trying to sift through their attachments to that land versus their other longings for home. And my dad and I started translating Chinese poems together. At first, I thought I was somehow procrastinating finishing Muscle Memory by accidentally beginning a different book, but ultimately, I decided that I had indeed written the poems that would complete Muscle Memory, even if they were entirely different from the poems I thought I had needed to write. Yes, the sweat and blood of the cage are in this book, but so is the thick smoke of controlled burns and the heft of roots and wet earth. Their presence in this book surprised me at first, but now I can’t imagine my project without them.