In every piece of art I create, I look for new answers to three central questions:

How can an inanimate object serve to create real, meaningful connections between people?

How can a change of perspective shed new light on a subject?

How can I, in my role as an artist, serve my community?

As an artist working in the public sphere, this has meant creating spaces, objects, and situations where people are invited to slow down and have intimate aesthetic experiences in parks, bus stops, train stations, and public buildings.

I have a deep affection and respect for the UArizona Poetry Center, and I was inspired to create an artwork that honored it. But it wasn’t clear to me what I could create that would enrich the experience of visiting the place. It certainly isn’t lacking culture—it is, of course, filled with thousands of artworks for people to explore. And the building itself is such a beautiful space, that there wasn’t any need to change the space in any way. The thing I love about reading poetry—the intimate connection between a reader and the text on the page—happens best in a quiet, comfortable space. The Poetry Center gives that to its visitors, and the last thing I wanted to do was to distract from that interaction.

So… what to do? The idea of a project for the Poetry Center sat at the back of my mind for years, without any way forward. What sort of artistic gesture is appropriate for a space that is already so satisfyingly complete as it is?

One thing I knew was that I didn’t want to use language as part of the artwork. I wanted to make something that would be a counterpoint to the poetry—something that honored what poetry was and could do, but in the language of visual art. Something that would be in conversation with poetry, but that was wholly its own.

In 2019, I started teaching myself how to make cloisonné: a very fiddly, precise, and time-consuming craft where layers of ground, colored glass is melted onto a substrate of copper with silver wires, then ground smooth. I had seen examples of cloisonné in museums, and was completely taken with the richness of color, the delicacy of line, and the small scale of the artworks. As a public artist who usual designs large-scale projects, working on the opposite side of the scale spectrum—to create pieces that focused the viewer’s attention so dramatically inward—was a very exciting prospect.

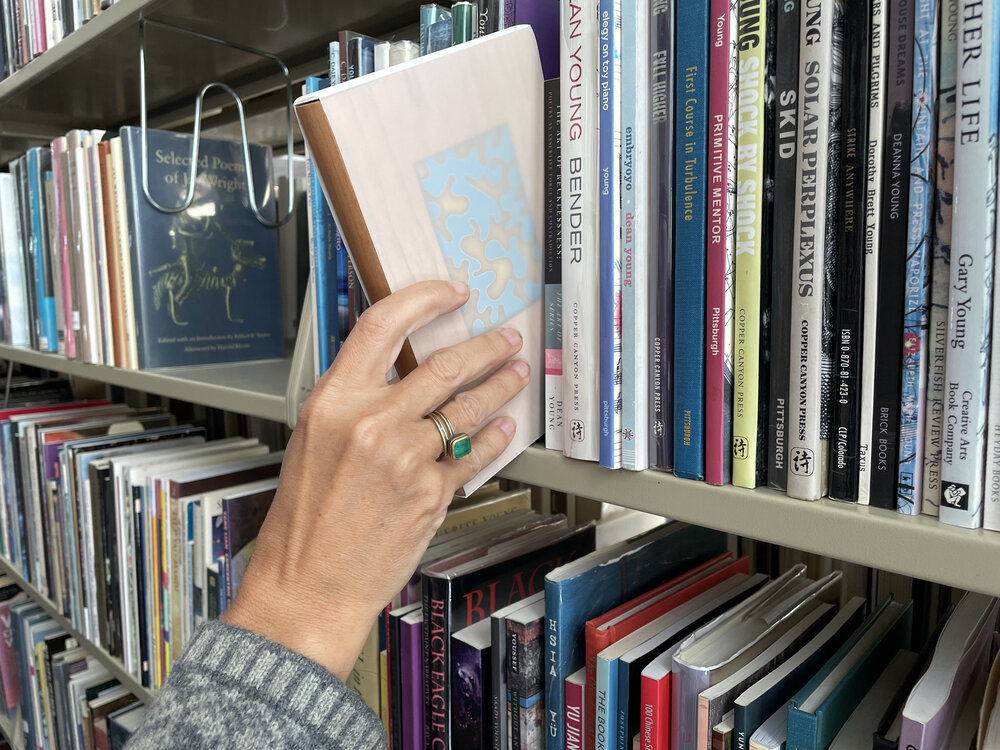

The idea for the Poetry Center project came to me when I realized that I looked at cloisonné enamels in a similar way that I read poetry. Their small scale asks the audience to slow down, to look closely and deeply. Rather than making a big thing for the space, I would work small… at the same scale as a poem. I could make artworks that would live on the shelves of the Poetry Center, where they could be discovered in the open stacks and enjoyed as visual counterpoints to the poems they would live between. People could experience holding and studying these small art objects in their hands, just as they would a book.

I proposed the project to the staff of the Poetry Center, who (I was delighted to discover) liked the idea as much as I did. I received a Research and Development grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts, which covered my time and expenses to work on the project.

As visual counterpoints to poetry, my initial idea was to try to make non-verbal versions of different types of specific poems – to ask myself what a cloisonné version of a sonnet or an epic poem or an acrostic would look like. Early experiments had identifiable illustrations in them, or multiple elements on a single board. But as I worked through these pieces, I realized that the core of the idea was to challenge myself to create the broadest variety of non-verbal, non-representational, purely visual experiences that I could, and that simplifying the format down to one element on each board gave me plenty of room to explore.

Dean Young—one of my favorite poets—wrote in The Art of Recklessness:

More than intending the poet ATTENDS! Attends to the conspiracy of words as it reveals itself as a poem, to its murmurs of radiant content that may be encouraged to shout, to its muffled musics there to be discovered and conducted.

I made this my goal in the studio: rather than (as I usually do) work through the design of an object in my sketchbook before fabricating it, I approached the copper and silver and glass with no idea what I would make, letting the manipulation of these materials dictate the direction of the pieces. I mashed and squished metal, I turned the kiln up and down, I layered and ground and re-layered. I did all the things to the cloisonné that books tell you not to do. I ended up with a very large pile of fractured and molten and blobby scrap; however, I also started to produce a selection of pieces that looked like nothing I had seen before in cloisonné – objects that seemed strange and interesting and beautiful enough to live among the poems that inspired them.

I chose 26 pieces that represented a wide variety of visual experiences and mounted them in book-sized panels made of wood (wood, the raw material of the paper books are made of, has a similar heft and warmth in the hand). The pieces themselves were set in the wood panels as poems are set on a page, presented one at a time for intimate contemplation.

To protect the neighboring books from the wood’s acid content, I developed sleeves with the help of the Poetry Center staff that would wrap around each piece. Removing the panels from the translucent material created a secondary reveal—an added bit of drama in the experience of examining them after pulling a piece from the shelf.

On a hot August day last year, right before the Poetry Center’s re-opening, my husband Bill and I drove down from Phoenix and spent the afternoon placing the pieces on the shelves, as if we were hiding Easter eggs. Some we placed next to our favorite poets, others were nestled next to books that seemed to rhyme with the abstract imagery on a particular panel. We saw these locations as starting points from where they would begin their lives in their new home. It has been a joy hearing how the panels have continued to migrate around the space as they are encountered by new visitors, celebrating the experience of discovery and contemplation at the core of the Poetry Center.

About Mary Lucking:

I create artworks that help people explore and understand the environments and communities where they live. My work ranges from large-scale, permanent artworks to temporary interactive installations. My projects include art incorporated into urban and rural walking and biking trails, public transit stations, college campuses, and neighborhood parks.

I currently live and work in Phoenix, Arizona.