In this column, Notes Toward Collaboration, we’re heading into the stacks and taking you with us. We’ll be writing about poetry and collaboration: questions of authorship, values, and processes. Like you might expect with a series of essays on collaboration, we’re thinking of this space as more discursive than authoritative, more reaching than arriving.

Each post will have a reading list of (mostly) contemporary volumes of (mostly) collaborative books. We want to map the field of contemporary collaborations and their poetics because we believe that collective writing is an essential tool for imagining a future which hasn’t yet arrived. What we find most exciting is that collaborative poetry NEEDS to be collaborative. We couldn’t read these kinds of poems from a single author because of the way they fuse more than one voice into a single narrative (or a resistance to narrative). They’re tactile poems that rely on more than one mind; they’re turn-based, cooperative, and so-on-poems with multiplicity in the mechanics. In the introduction to Saints of Hysteria: A Half Century of Collaborative American Poetry, the editors consider what work exists in the vein of “collaborative impulse”: poems that “bicker and blend,” poems that rely on the tension (and the conduit) of more than one author working in congress.

There is so much beauty in that collaborative impulse, those chance encounters where poems overlap, and the limitless directions dictated by two or more independent minds. From the perspective of process, the unexpected nature of collaborative writing makes it a sharp tool in any creative practice. Through collaboration’s third voice, writers can (re)discover parts of the self. Some skeptics argue that collaborative poems are only for its practitioners, that the value in collaboration exists in the doing. We believe it’s often also necessary reading. In fact, it is the squishy, open-ended, (at times) circumvential qualities of collaborative writing that creates engaging, valuable texts.

Take, for example, “The Desert Survival Series/La serie de la sobrevivencia del desierto,” a part of the Transborder Immigrant Tool created by Micha Cárdenas, Amy Sara Carroll, Ricardo Dominguez, Elle Mehrmand and Brett Stalbaum of the Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT) 2.0/B.A.N.G. Lab. Built out of activism and necessity, this multilingual, digital collaboration exists as a GPS location tool giving physical markers and poetic advice on crossing the Sonoran desert in English, Spanish, Arabic, Brazilian Portuguese, Greek, Taiwanese Mandarin, and Malayalam. It took shape in direct response to US border enforcement. The twenty-four poems, written one for each hour in the day, begin with these words:

The poem is a result of many hands, in terms of the voices of translation but also in terms of the origination of the writing. Amy Sara Carroll explains the poems’ genesis: “I turned to texts about desert survival: handbooks, military manuals, a guide for border-crossers briefly distributed by the Mexican government. I divvied up (with the help of Brett and others) the information I found–the indispensable from the expendable. I wrote pared down prose poems, ideologically neutral (Is any writing ‘ideologically neutral’?), procedural, if you will–a poem about locating the North Star, a poem about what to do if you are bitten by a rattlesnake or tarantula, poems that contained details about how to weather a sandstorm or a flash flood.” The input from her collaborators shaped the materials she used, in the same way coding the app alongside her collaborators shifted the poems. This project is both multi-authored and multi-medium.

As another example, UK-based SJ Fowler’s The Enemies Project has spanned years, continents, and many languages. Because The Enemies Project is process-based, performative, and purposefully pairs writers working in different modes and aesthetics, it has been described as “a landmark against factionalism in the UK literary scene.” We’re interested in collaborations like this one, where writing in groups is used to deliberately bridge divides.

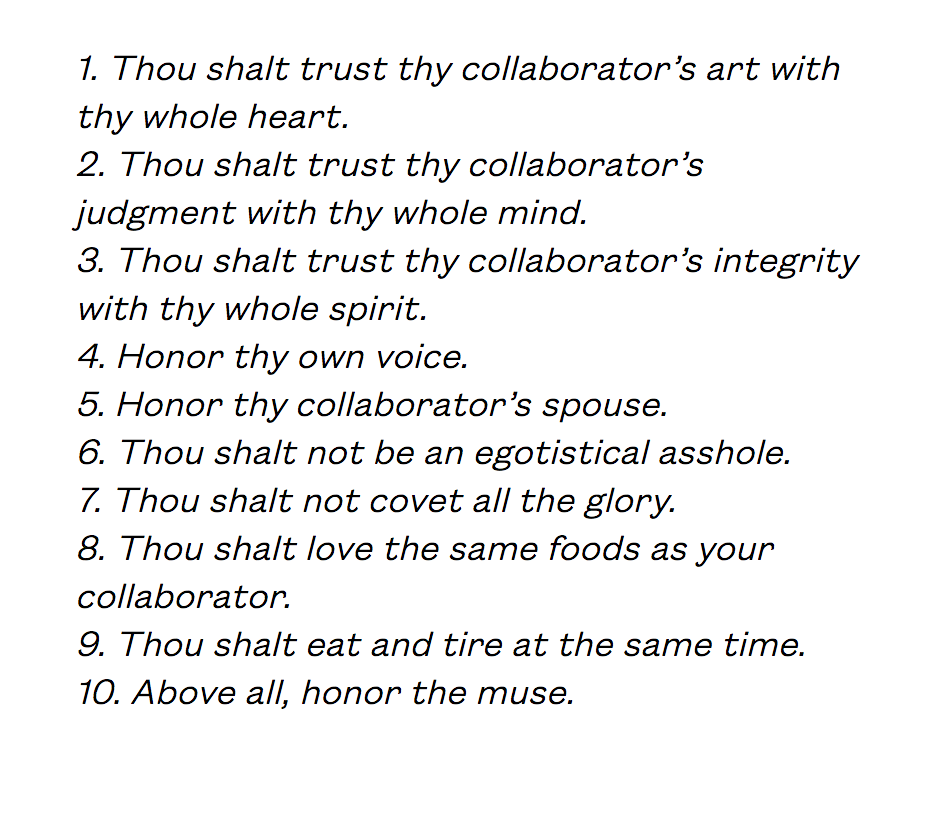

We’re also interested in the effervescent quality of writing with others: that crackling, delightful potential of an animus no one person knew before they joined a chorus. Take, for example, the work of Maureen Seaton and Denise Duhamel, who have been writing together for over a quarter century. With a nod to the surrealists, their collaboration is built on friendship and play. You can see evidence of this in their Ten Commandments of Collaboration:

Alli Warren writes on the Harriet blog, “If I’m being bold,” (Yeah! Do it, Alli!) “I might even say that collaboration is one way to expand the boundaries and limitations of subjectivity.” This exactly, yes, yes, yes. And how does this happen? We’re writing this column in order to trace the process: how collaboration teams form, come to consensus (or otherwise agree), compose, and revise. We’re also keenly interested in the results: how do these texts expand boundaries and re-envision the world? In some ways, this column will follow our individual and collective interests: ecopoetry, queer poetics, the formation of an “other” voice, and the ethics of collective authorship. But we also aim to make our reading wide-ranging and inclusive. These essays will serve as reference materials, pointing to collaborative works and the worlds from which they came. We’ll be collecting resources that will help first-time and seasoned collaborators as well as educators and librarians. In doing so it is our mission to add these essays piecemeal into the greater conversation surrounding multi-authorship writing.

We aim to delve into the stacks of our local libraries and hope you will, too. We want to hear from you. What are you reading? What have you written? How do you include collaboration in the classroom? Please get in touch with us: collaborativepoetics [at] gmail [dot] com.

Curtis Emery and Laura Wetherington are poets who sometimes write poems together. You can see their collaborative work in Past Simple and forthcoming in ELDERLY.

READING LIST

- Saints of Hysteria A Half-Century of Collaborative Poetry edited by Denise Duhamel, Maureen Seaton and David Trinidad.

- The Desert Survival Series/La serie de la sobrevivencia del desierto, by Micha Cárdenas, Amy Sara Carroll, Ricardo Dominguez, Elle Mehrmand and Brett Stalbaum.

- “The Transborder Immigrant Tool/La herramienta transfronteriza para inmigrantes” by Amy Sara Carroll

- The Enemies Project by SJ Fowler

- Poetry and Collaboration: Denise Duhamel and Maureen Seaton, an interview

- “On Collaboration” by Alli Warren