I just really felt the need to explore these voices

that had been extinguished.

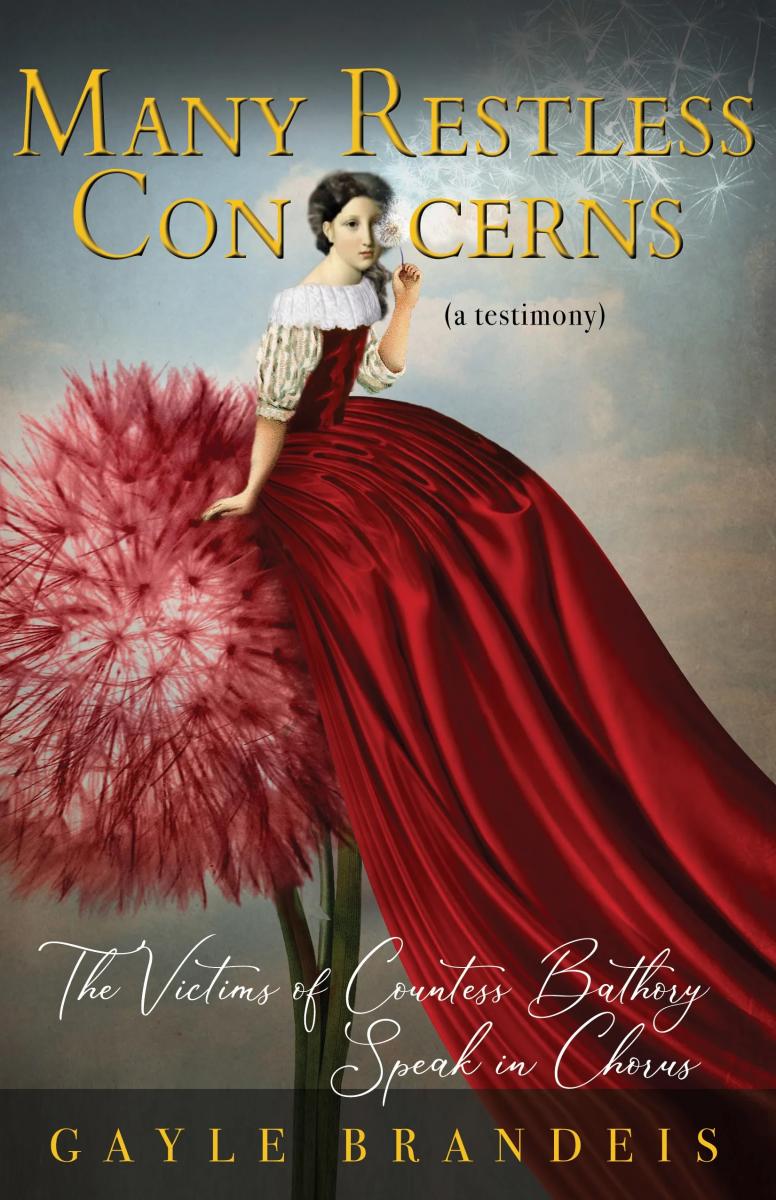

Gayle Brandeis’s nine books cover multiple genres: poetry, essay, memoir, novel, and writing advice. Many Restless Concerns, her most recent book of poems, is a novel in verse. It traces the historical record of the Countess of Báthory, who was accused of murdering hundreds of girls and women in Hungary in the late 1500s. This book is a wake, spoken by a plural voice of the murdered, giving space to the imagined parts of history left unrecorded. The diverse forms of the book’s forty sections span free verse, prose poems, composition by field, tercets, and monostiches. The poems begin in a chorus, but dip periodically into a singular “I.” There’s beautiful finish-work in these pages, like the white space between verses in the section on nettles punctuated with a pointed star, eye-rhyming its sting. I was fascinated by the use of the first person plural and Gayle’s acrobatic movement from intense historical research to creative storytelling, so we spoke over Zoom about the making of this book.

**

Laura Wetherington: Did you have some kind of question in mind when you came to this work – like about humanity, or about women, or about something else? And then, if so, did the writing answer it?

The first person plural voice was there from the start.

They wanted to speak in a chorus.

Gayle Brandeis: I just really felt the need to explore these voices that had been extinguished. I came upon this project in a very unexpected way. It's a book I never could have anticipated writing, but my daughter, when she was a teenager, was really interested in notorious women in history: pirates, outlaws, various folks like that, and she would ask for books on the subject and they were fascinating books, so I thumbed through them myself.

There was one book that was an encyclopedia of notorious women, and there was one chapter about Countess Báthory, who I somehow had not heard of before. I'm not sure how I managed to escape her story up until my forties, but there she was. I found myself really haunted by the fact that she had killed so many girls and women. Allegedly. And I couldn't get that out of my head, that there were all these girls and women, mostly poor, in dire straits and having to work for her to be able to survive, who were snuffed out – their voices, their lives, their futures – by this woman in power. I don't know why that just wouldn't leave my mind, but I kept thinking about them and I thought maybe I would write a poem or two and explore them, so I started doing some research. The first person plural voice was there from the start. They wanted to speak in a chorus. After I wrote a couple of poems, I just kept writing them and I thought, OK, this is more like a cycle of poems. But then they kept coming, and I realized it was a larger project.

But at the time, I was pregnant with my youngest son. It started feeling a little icky to be writing about torture and murder while pregnant. It just felt like maybe this isn't the healthiest choice for me right now.

LW: Yeah.

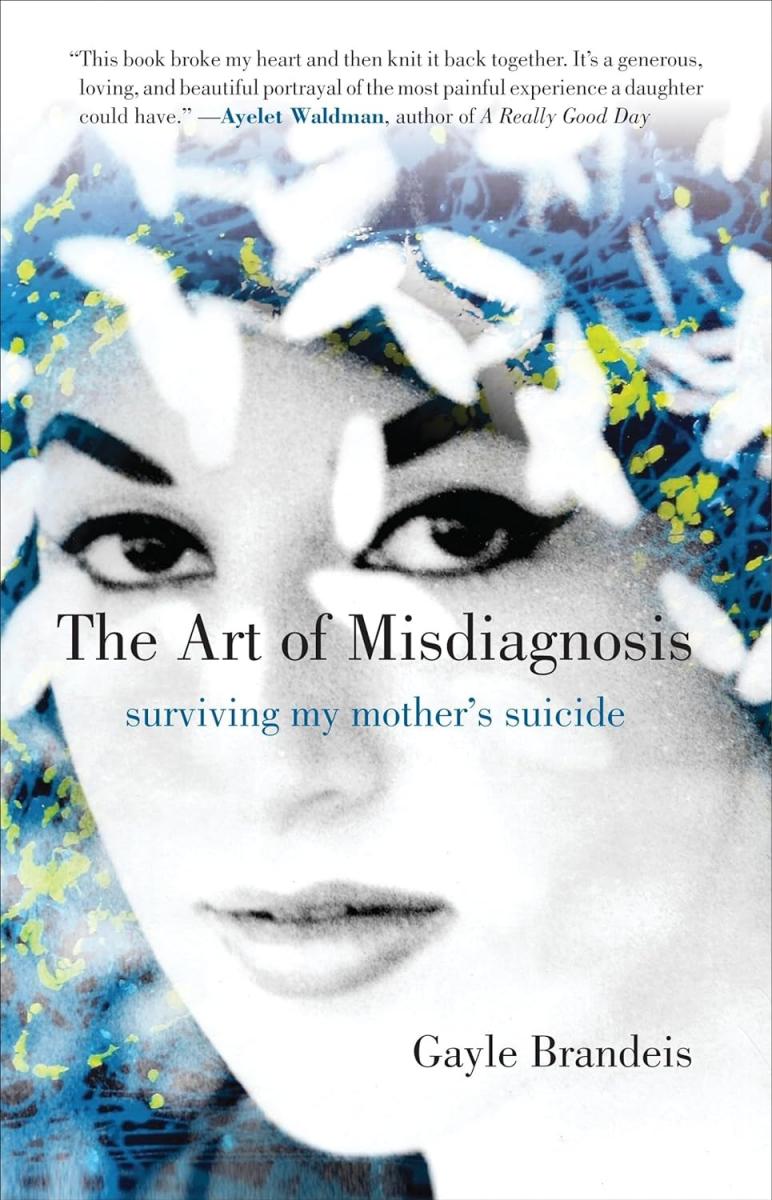

GB: And so I set it aside. And then when he was one week old, my mother took her own life and that became the thing I needed to write for the next few years. Writing's how I figure stuff out and process, and so that became the focus of my work for several years.

When I finished writing my memoir, The Art of Misdiagnosis, I felt really lost because that project felt so urgent and so, so necessary. It was the most important thing I'd ever written. I thought, how’s anything I ever write going to be meaningful after writing this project? Even though I've been writing my whole life, I was kind of worried that maybe I was done as a writer, that that was my sort of swan song as a writer. But then I remembered this Báthory project I had set aside. I started looking at these poems again, and they felt really alive to me, and that threw me right back in. It felt like a good book to follow up the memoir because after tackling my own grief, exploring a larger grief felt meaningful and felt like a good next step. I

felt ready to do it because I had been so immersed in writing about grief. It didn't feel icky anymore, or unhealthy. It started to feel necessary to me and it started to feel like a little act of justice to restore some sort of voice to these girls and women who had been silenced. So I threw myself back into the project and it became what it ended up being.

after tackling my own grief, exploring a larger grief

felt meaningful and like a good next step.

LW: Wow, you’ve just said so many things here that touch on all the questions that I have. So I'm really excited to hear this introduction and how the book came about. And that it surprised you. And that it seemed to just come right out. The fact that there's this chorus speaking after the women and girls have died makes it so that you can have this omniscient narration. And if I understand this correctly, you chose the moment of the Countess Báthory’s death as the moment where these voices are telling the story, is that right?

GB: Mmm-hmm.

LW: So the choral voices came to you, but once you started with the first person plural, what did you discover that you were able to do with that?

GB: These women and girls were pretty voiceless even when they were alive because they were poor and had to take on work that was in service to power, and I'm sure their voices were not welcome in the castles and various places like that. In joining their voices together, they could find a power that they hadn't found in life together. It gave me chills to think of them being able to speak together as one, to feel that source of sisterhood, solidarity: bringing their voices into something that was bigger than themselves, but also gave them their own power, too. And I wanted to have reminders that there were individuals within this collective, so I would pull out the individual voices here and there just to keep that awareness that this choral voice was made up of individual girls and women who had something to say and who had lives worth telling.

In joining their voices together,

they could find a power that they hadn't found in life together.

It gave me chills to think of them being able to speak together as one,

to feel that source of sisterhood, solidarity.

LW: I thought it was super-powerful that you begin with a chorus to establish the story, then introduce like five singular voices in succession, so there's still a kind of power generated. Are those singular voices, which come out in various places in the book, recurring voices in your mind? Or, at every point you hear a person say “I,” is it a new person?

GB: Ohh. I haven't looked at the book for a while, but I think there's at least one voice that recurs.

LW: The one who was a potter, says, “the clay saved me” and in a later poem has to crouch in the giant pot?

GB: Yeah, yeah, yeah...

LW: Along this same line of choral speech, what happens at a reading?

GB: I've loved to do readings for this book because I've always asked other people to read with me, to make it choral with at least one other person. I've often invited audience members to be part of it, too. And so I’d have pages printed out with different sections highlighted so there would be their individual voices, but then parts where we would speak in chorus, and that felt so important to me to have it heard in a choral way. And then the most incredible reading experience I had was actually right before everything shut down for the pandemic. I had to cut my book tour short because it came out in February of 2020 and I was doing some events and had some planned for March that were canceled. But the very last one I did before things shut down was in Riverside, California where I used to live. A friend of mine who is a playwright, she adapted it into a multi-voice piece and she invited members of the community — many of whom are friends of mine — to read. There were twenty voices. And it was so incredible. And she has since adapted the whole thing into a stage production and I'm excited to see what will come of it. But yeah, being able to be in this room and hear so many voices together, it just rattled my bones. It was so powerful.

LW: Ohh my gosh amazing. Ohh that's the perfect way to hold and carry these voices. That's great.

In the acknowledgments you say “this was informed by history, but it's very much a work of the imagination,” and I'm wondering if there was a general philosophy or ethics that helped guide you between these two poles. Can you talk a little bit about how you made decisions about this?

GB: Yeah. Yeah, I think it had to be an act of imagination in some way because there wasn't any information about these girls and women. I think one person was named in the transcript of the trial that I found. But I wasn't able to find out much about their individual lives and so I had to research what life was like during that time, what people wore, what people ate. Just things of that nature. I had to create some representative individuals out of that research because they're lost to time.

LW: Hmm. But how did you know what to leave in or what to leave out with these people who were real but needed some kind of animation?

GB: I think as I was doing research, the details that felt most alive to me were ones I utilized for the work. So things like the cooking of the plums, or the pottery. I really trusted my gut with the research. If I felt a little ping inside of me when I read the detail, I would write it down and try to fold it in in some way. So it's really looking for those details that sparked me and that felt alive to me and felt like they could help bring these people to life – those more specific kinds of sensory things that could evoke a felt life and the actual embodiment of the people who lived in that time.

I really trusted my gut with the research.

If I felt a little ping inside of me when I read the detail,

I would write it down and try to fold it in in some way.

LW: That's really helpful. And like, what about the forest witch? Was that a myth from the time that you folded in or was that fully invented?

GB: That was from folktales that I found. I ended up folding in various folktales, like the one about the girl who becomes an apple. I found the Hungarian folktales really enriching and inspiring.

LW: That leads me to this more kind of technical question. Because in the back, you have this list of books that you read about the Countess Báthory, a lot of stuff, but now you're also talking about folktales. And so there must have been so much that you were reading during this time. And in the acknowledgements, you say that the project began in 2009, but then the book was published in 2020, almost a ten-year period. So how did you keep the facts and the details and the workflow together over this long period of time where there were breaks in between?

GB: Yeah, there was, you know, that long like seven-year break where I didn't look at it at all. It was kind of shunted off to the back burner of my life, but I did have notebooks full of research, with some of those details that I found most evocative and compelling. When I returned to it, I had those waiting for me, but I also dove back into the research and just started kind of trawling for more resonant details and for important information I may have missed before.

LW: You know, there was also this difficulty you talked about when you were pregnant and took a break. But were there other things that you did or advice that you have for folks who want to write about super-difficult subjects? Like, how to sustain and take care of yourself during that?

GB: Yeah, I think that's so important because it can be very triggering to write about hard subjects, whether they're from our own experience or something outside of our experience that still resonates with us. Grounding practices are really important. I found that both with this book and with my memoir, I would literally ground myself by lying down on the floor. That became sort of an intuitive grounding practice. If I felt overwhelmed, I would lie down on the floor and feel the earth holding me and just sort of bring myself back into my body. And remind myself that I was in that present moment, that I was safe. And I would be able to calm myself that way and center myself that way. But I think whatever grounding practices people have, whether it's, you know, breathing practices or walking or dancing or yoga or anything, just listen to your body. I think our bodies will tell us when we need to take a break. Sometimes it's a long break. It's all about trusting that physical response to the work and caring for ourselves.

In terms of other practices, just setting time limits can help in terms of knowing that you have a way out, like you have a set endpoint, and you can exit that hard place and get back to your life. That's an option. And just checking in with yourself before you sit down to write to see what you have the bandwidth for. Maybe some days writing something that's a little bit less painful is necessary and just waiting to be ready to write the rest. Like, with my memoir, there were certain scenes that it took me years to write because I just—I just couldn't face writing them. But at some point, I felt ready and I don't know why. I could tell that I felt ready. And then I wrote all those scenes in a day, like just all of them. They just came pouring out once I was ready. I think sometimes we have to trust, like, when we need a little bit of time. But if we're taking too much time and we're just being avoidant, giving ourselves little prompts or constraints that can help us get back into it can be helpful.

LW: Ohh, that's so great. I mean, wow, I was asking that question for me. So thank you. For all of this.

___________

Gayle Brandeis is the author, most recently, of Drawing Breath: Essays on Writing, the Body, and Loss (Overcup Press). Earlier books include the memoir The Art of Misdiagnosis (Beacon Press), the novel in poems, Many Restless Concerns (Black Lawrence Press), shortlisted for the Shirley Jackson Award, the poetry collection The Selfless Bliss of the Body (Finishing Line Press), the craft book Fruitflesh: Seeds of Inspiration for Women Who Write (HarperOne) and the novels The Book of Dead Birds (HarperCollins), which won the PEN/Bellwether Prize, Self Storage (Ballantine), Delta Girls (Ballantine), and My Life with the Lincolns (Henry Holt BYR), chosen as a state-wide read in Wisconsin. Gayle teaches in the low residency MFA programs at Antioch University and University of Nevada, Reno at Lake Tahoe. She currently lives in Highland Park, IL with her husband and youngest child, where they've just opened Secret World Books.

Laura Wetherington is a poet living in Reno, Nevada. She teaches with the International Writers’ Collective and the University of Nevada, Reno at Lake Tahoe Low-Residency MFA. Her latest publication is Little Machines.