What is this thing we call Voca? The name gestures toward the human voice (in Latin it means roughly “call!”) and we liked the sound of that! We used to call it “The Audio Video Library,” but that name felt too formal and clunky. So in 2012, we gave it a new name.

Voca.

An audiovisual archive.

...

When you think ‘archive,’ what comes to mind? A labyrinth of shelves? Sealed boxes furred with dust? Something closed, distant, lost, or locked?

I guess I’ve always thought of archives a little like that—treasure-boxed and tucked away. A collection, sure, but behind glass. Not for touching.

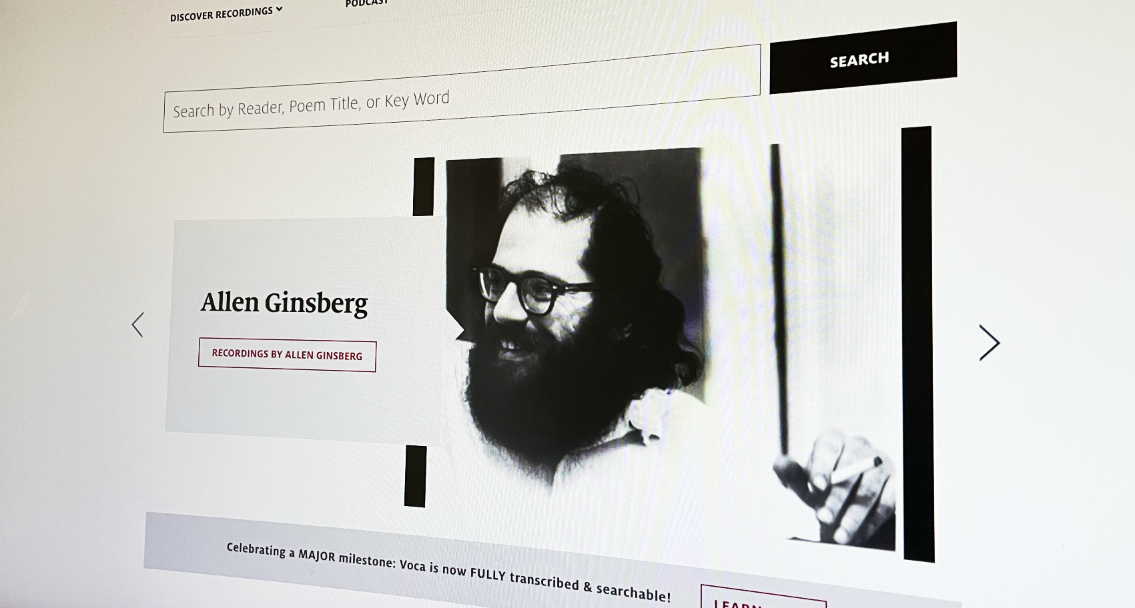

Voca is different. Digital. Explorable. Accessible. Unduplicable. It invites you in. It’s a living archive, with new additions added every day. It has captions and transcriptions and tags and navigable tracks. It houses poems that exist nowhere else—unpublished poems shared only at the readings, poems that differ from the versions published in books. Voca not only stores the reading themselves but that magic detritus that happens between poems, the little jokes and outbursts and questions and delights that happens just once because even if a poet has read the same poem thousands of times, each time was actually (a little) different.

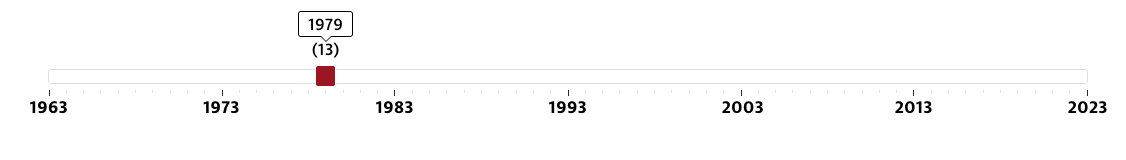

The Voca collection is vast—documenting the work of emerging voices alongside literary luminaries. Many writers have read at the Poetry Center multiple times over the decades—including upcoming 2024 readers Brenda Hillman and Robert Hass who have recordings that date back to the 70’s! And what a gift it is to go back in time to experience their maturation over the years as they’ve grown into their styles, subject matter, and voice. That whole life-long metamorphosis lives on in Voca.

“The archive is also consistently intertwined with pressing social issues,” Library Director Sarah Kortemeier adds. “Voca features rich collections of readings on climate justice and climate change, indigenous writing of the Southwest, Chicanx and Latinx writing, and racial justice.”

That’s really (part of!) what makes Voca so special. It exists in context. It exists in and through time. And when you go back to listen and watch and read it for yourself, you become a part of that context. Marianne Moore called poems “imaginary gardens with real toads in them,” and I like to think when you dip into the Voca archives, you get to amble that garden, you get to touch those toads.

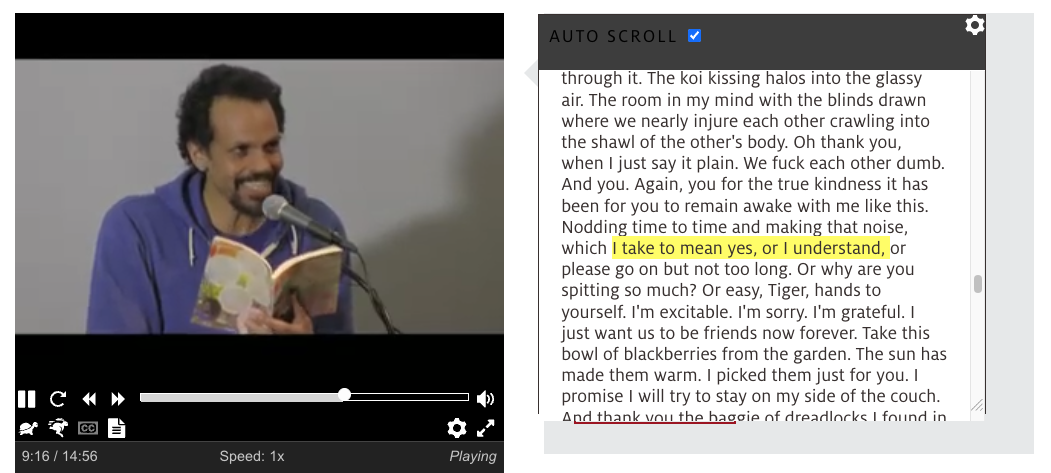

One such toad: Ross Gay reading from 2017. He’s reading his poem “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude” and right around the 9 minute mark, he describes that thing we do at poetry readings: “Nodding time to time and making that noise, which I take to mean yes, or I understand, or please go on but not too long.” He’s describing those little involuntary noises of appreciation that you hear so often at readings (and I am so often guilty of making, hand over heart)—the sound that does mean ‘yes’ but also ‘whoa’ and ‘holy shit’ and ‘I get to inhale the exhaled air that was used to form those words???’

And I wasn’t actually there, in the room, when Ross Gay read in 2017. But I’m here, now, my headphones cupped over my ears like two warm hands. When I hear him, and I hear the burbles of laughter he elicits, and I see the way he leans on the podium, taps it with one hand, and I follow along word for word with the captions, what he’s said, he’s saying, he says—I’m transported. I’ve gone back in time, and it happens to me too. I am there also. Yes.

...

And there's more: I’ve been transported by the Poetry Centered podcast. Poetry Centered was originally a pandemic project, a way for folks to continue engaging with poetry when we were all isolating from one another. But it’s evolved into a living tour of the Voca archives. Each episode, a different guest poet curates three poems from the archive, sharing their insights about the remarkable performances. You couldn't ask for better guides: Maggie Smith, Ada Limon, Manuel Paul Lopez, Sally Wen Mao, and many, many more.

They bring you a foraged bouquet, a ‘flight’ of poems, hand-picked, hand-poured. Cup your hands and catch them.

...

In a way, Voca is a living museum of poetry readings. Over the past couple of decades, we’ve collected thousands of recordings for the Poetry Center’s long-running Reading and Lecture Series—with recordings that date back to 1963 all the way up to today. At the time of writing, our most recent archive addition is Eileen Myles reading at the Poetry Center in October 2023. And our librarians are hard at work transcribing and archiving new recordings every day.

As we’ve recently added captions and transcriptions to the archive, one thing we’re surprised by is just how much multilingual content the archive holds.

“I expected to find readings in Spanish and in Southwestern Indigenous languages in addition to English, all of which we have in abundance,” Sarah Kortemeier expressed, “but we’ve also got folks reading in modern and classical Greek, Latin, Polish, Russian, Chinese, Japanese, German, Italian, French, Bosnian, Arabic, Swedish, Hebrew—the list goes on and on.”

This means Voca isn’t just a bunch of recordings from some building in Tucson, Arizona. Voca preserves voices from all over the world: it is an internationally significant poetry archive.

Why does this matter? Because an audiovisual archive like Voca is one way to ensure that poetry belongs not to just those who were in the room when it happened, but to everyone. You can drag a slider and go back in time. You can find poems tagged cactus, vespers, ghosts. You can hear the crackle of the recording before Alice Fulton begins reading “Traveling Light”—which of course, isn’t just her reading her poem, but explaining where the poem came from, like she’s performing a poetic autopsy:

“I had just finished graduate school and for the first time somebody had given me some money and said, go ahead and write. And this had never happened before. My reaction to this was guilt, which I don't recommend. I think it's really unproductive and stupid.”

I love how her introduction sets the table for us to receive her poem. She isn’t explaining what it means or what we’re supposed to ‘get’ from it. She’s opening a window, letting a little light in. When she reads the lines, “Behind me, the ocean stares down the clouds, the little last remaining light, as if to remind me of the nothing”—here she pauses, lets us float—“I will always have to fall back on.”

It’s long been impossible to define what poetry is, what makes it so significant. Emily Dickinson once wrote in a letter that “if…it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me I know that is poetry.” You can think of it as “stored magic” (Robert Graves) or “language in orbit” (Seamus Heaney) or “the record of the best and happiest moments of the happiest and best minds” (Shelley)—and I often do. But I get to click a button, like this big red one here, and I get to step into poems as if I’m landing on another planet.

Wow.

Voca

Voca features 1000+ recordings from the Center's long-running Reading & Lecture Series and other readings presented under the auspices of the Center. We are constantly adding the latest recordings from the Center's ongoing reading series, along with newly digitized content from our five decades (and counting) of history. With the addition of these new features, lovers of poetry will be better able to share and experience this rich archive for years to come.