“The metal womb knows nothing of submarines,

but that is how she thinks of herself: a submarine…”

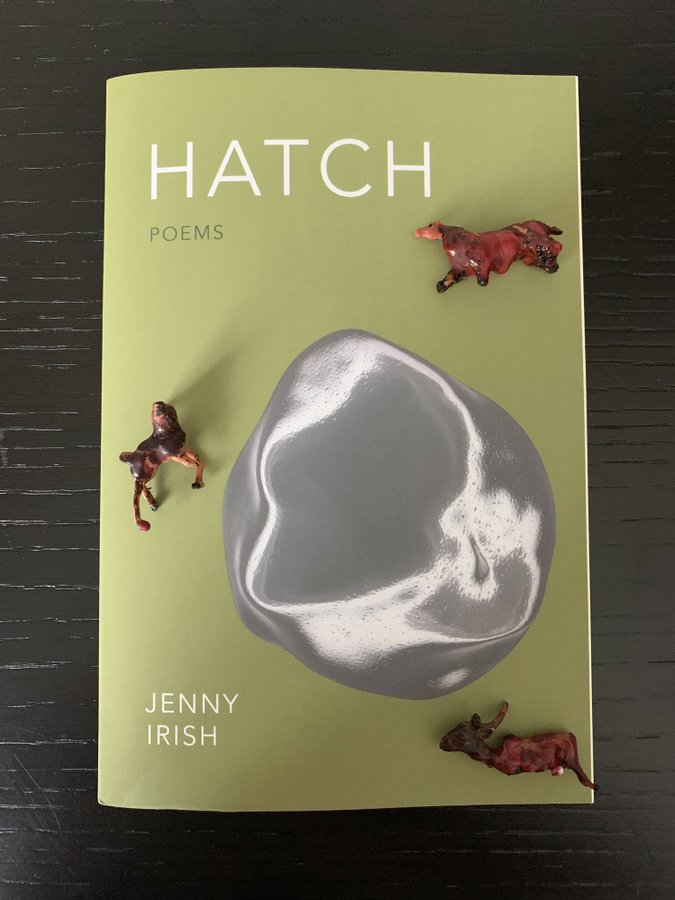

I was sitting at Gate D1 of the Harry Reid International Airport feeling completely drained when I cracked open the cover of Jenny Irish’s fern green Hatch. That’s a fib, of course, because my trip to Nevada took place before I received the hard copy of the book. Instead, I read Hatch on the same laptop that hours later, had been the instrumentality of assessing my ability as a professional. My introduction to the “city of sin” has been through its posters: posters of help for victims of trafficking in different languages, lawyers’ advertisement to families of victims of personal injury and criminal defense (paraphrased as: “did you come to Las Vegas to gamble and get in trouble with the law?”), and now across from me, a poster against child trafficking. That sense of unease sparked by the girl model featured in the poster was helped by the countdown as I entered the world of Hatch, a book that is centered around the metal womb, the almost-spherical, somewhat indented matter that combines a metallic sheen with the gray soup of the unknown.

I begin Jenny Irish’s prose poetry collection with the poem “USS Narwhal.” It begins: “The metal womb knows nothing of submarines, but that is how she thinks of herself: a submarine…” Having read Irish's Lupine, her previous collection which reframes the feminine monstrous, I was immediately anticipating the metal womb to detonate and obliterate the concept of a belligerent patriarchy. Soon, I thought, the bloodbath shall commence. I had played Jax’s “Cinderella Snapped” (a song recasting Disney Princesses as CEO’s, biomedical scientists, etc.) on a loop to calm myself down before the exam and so I was expecting a turning-the-table epic. Maybe this is the way my brain (cooling down from overuse) conceived of getting back at how I and the metal womb are objects from which things of value are extracted.

The metal womb is disturbing, bordering on the grotesque, because of what she is used for, in being “seeded and harvested, and seeded and harvested again” and because she has grown “makeshift hands” and a “conceptual grasp of clit.” Most of all, I was discomforted by the metal womb because I was not sure how I should feel about her. I don’t want to be that fool who mistakes artificial intelligence for the human, or that psychopath who mistakes humanity for a misunderstood entity. She can think but her thinking is delimited by her “vague memory” in the form of cellular memory.

The metal womb is disturbing, bordering on the grotesque,

because of what she is used for, in being “seeded and harvested,

and seeded and harvested again”

There is a disturbing proximity to gender-based violence masked by generalizations of the metal womb as an artificial creation. There is also an uncanny similarity between the metal womb and the famous "Hello Kitty," who is designed without her mouth because that would then allow her viewers to project their emotions onto her. Her feelings are beside the point. What is female is designed to not have a mouth, so that the people who play with her can feel empowered over her.

In Hatch, the metal womb does not have legs with which to move. She is unable to scamper. Instead, the tiny protrusions she calls her “hands” are appendages that cannot serve as tools. I was immediately reminded of poet Molly Zhu’s series of poems about girls playing various roles, like the “Girl with No Hands” on Tupelo Quarterly, which begins: “The girl with no hands actually does have hands, it’s just—they are invisible and she only makes use of them to serve herself.” For a long time, I wondered about the girl in Zhu’s poem: Why is it necessary for the girl’s hands’ to be invisible for her to not have to give the men in the poem a blow job, or to take notes for her male superiors? She (be it the metal womb or the girl) was always pressured like the beautiful wife of the Doctor was pressured to say only “yes.”

As I continue through Irish's collection, I meet other characters that share the plight with the metal womb: the female laboratory intern who was assaulted by the male intern; women who ran away from sexual abuse; the human mother subject to the needy demands of children. In reading, it becomes clear that the metal womb is stuck where she is at. She has no superpower to save herself. Like the magician’s beautiful wife, the metal womb is expected to say “yes” to every demand. I was so sick of saying yes, and of women being expected to say yes, and Irish captures that with the precision of a historian who mixes fables and facts, from etymology to artificial intelligence and factoids about childbirth and medical diagnoses.

I was so sick of saying yes,

and of women being expected to say yes,

and Irish captures that with the precision of a historian

who mixes fables and facts

On the five-hour flight from Las Vegas to New York City, we were packed like sardines. I started to type up this “enthusiasm” next to my snoring (male) neighbor, who had manspread into my personal space. It was midnight and I had my lights on. I shook my head and turned my attention to the titles in Hatch, which are pithy, witty, and creates narrative tension. Rather than “Don’t Be Afraid,” we have “Be Afraid,” in which Irish writes:

In the twenty-first century, a popular show belonging to the subgenre of reality television (reality, in this case, being a subjective descriptive, as many of the most successful titles, were, in fact, highly scripted) operated on the following premise: one man and one woman would be deposited, naked, in an inhospitable wilderness, with limited man-made resources (a magnesium fire starter, a knife, a spool of Paracord) and then filmed in their attempts to bond, build shelter, gather food, make fire, and secure drinkable water—a twenty-one- day extreme survival challenge from which emerged an unsettling gender binary.

We expect the guy-meet-girl to spark romance in the shared flight from plight. Isn’t that the sweetest thing? we might say. In our romanticism, we may forget about the frequency of sexual violence:

Male contestants also identified Earth as a female entity but did so by emphatically stating how hard and with what frequency they were going to rape her. (They did not, of course, say rape, relying instead on words like 'dominate and own, paired with phrases like, She can try to make it hard for me, and Shane or Luke or Jeff or Todd always gets his.)

What is unsettling is that this archetype of “Shane or Luke or Jeff or Todd” has thrived within modern culture. We have The Bachelor, Love Island, Single’s Inferno, and other reality dating shows that are scripted to create drama from the real mental breakdown of the contestants. The graphic nature of the glee with which the men describe the domination and the ownership of the Earth—like the subjugation of the metal womb—parallel the reality which the reality show depicts, false premises aside. In Irish's poem “Potent,” the mythos is such that the metal womb “wonders, why it is easier for these men to imagine vampires and tortured babies than it is to accept science, to admit their own complicity.”

This archetype of “Shane or Luke or Jeff or Todd”

has thrived within modern culture.

What matters, then, perhaps is less what is said, but what is uncovered by what is unsaid. In “France is America’s Oldest Ally,” Irish asks, “could it also be argued that to make a name unspeakable is to illustrate the influence of its owner, an unintentional but nonetheless clear acknowledgment of the power that they do possess?” It’s like Voldemort in Harry Potter, where the very articulation of the unsayable is a show of power of the tormentor, where our fear is hushed to a whisper.

While there is ambiguity as to the extent of the metal womb’s sentience and her true relation to the children sprouted within her, the ethics proposed by Irish is crystal clear: the situation the metal womb found herself in is wrong. As I drifted into and out of sleep, I read factoids to demonstrate the biases inherent in the American political sphere, how “objectivity” is distorted by our unconscious biases and more pernicious prejudices.

Just as the closed fictional world of the metal womb posits the female womb as an object of extraction, the real world, Jenny Irish reminds us, contains similar prejudices that render even our laws and scientific medical prognosis suspect. That’s the shock power in her statistics, presented to show parallels between the plight of the metal womb and women, including women of color, who are frequently misclassified as a criminal subject, and whose medical complaints are improperly dismissed as petty—frequently by a predominantly white, male officers and doctors.

This reflection of social inequities embedded in our legal and medical institutions is shown in “Severe Deficits,” where Irish writes: “In Washoe County, Nevada, parents stand outside an elementary school gathering signatures on a petition requiring teachers to wear body cameras to ensure they do not teach critical race theory. In Washoe County, Nevada, parents stand outside the sheriff’s office gathering signatures on a petition to abolish requiring body cameras on law-enforcement officers.” Having just been in Washoe County myself, I ponder a while on Jenny Irish’s framing which implies that all parents in Washoe County, Nevada are encouraging body cams on teachers and forgoing body cams on police officers. It felt heavy because the truth is that the loudest among us, purporting to speak for all of us, may not actually have a majority behind them, including those of us who are disempowered after the overturn of Roe v. Wade. Hatch doesn’t mention this, but just 11 people are responsible for 60% of the book ban challenges in the 2021-22 school year.

(Might there be change if Irish’s framing changes? This is so depressing.)

I won’t spoil the book’s ending but at 5 a.m., as the plane prepared for its landing, I was no longer looking for a dismantling of the patriarchy. Instead, I was changed by the emotional cadences of the women in Hatch who try to escape the nightmare, which takes the shape of a mare at night in post-Roe America. The clever wordplay and the use of etymology digs into the root of things in the same way that Irish digs into the underlying structural basis of misogyny and social wrongs. At her end, however, the metal womb does not represent her victimhood but a new beginning ,where she voices her care in the way that she knows how, in a "percussive message across her skin.”

I return to that percussive message this evening as I behold the metal womb’s dream filled with the bioluminescence of the fireflies, whether in the yellow field or in a jar. Hatch teaches me that dreams can occur even in the darkest of places, even by the weakest among us, even if it feels like everyone else is seeking to repress us. The truth can be much brighter, if less garish and oppressively loud. Now, when I cannot sleep at night, I think of the fireflies, flickering light like the percussive message of the metal womb and revisit Jenny Irish’s stellar new collection.

_______

Tiffany Troy is the author of Dominus (BlazeVOX [books]) and co-translator of Santiago Acosta’s The Coming Desert/ El próximo desierto (forthcoming, Alliteration Publishing House), in collaboration with Acosta and the 4W International Women Collective Translation Project at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is Managing Editor at Tupelo Quarterly, Associate Editor of Tupelo Press, and Book Review Co-Editor at The Los Angeles Review.