there’s a thing called a sentence.

What can it hold? Can it hold all the possibilities?

________________________

Jason Magabo Perez: Thank you MT for agreeing to have this conversation, a generative conversation on poetry and poetics; Filipino studies, critical ethnic studies, our training, and maybe even our overlapping affinities with certain poetry communities. Also around our books, both What You Refuse to Remember and my recent book, I ask about what falls away.

I’m going to start with a general question. How do you navigate the project of poetry, poetics, queer poetics, within the specific field of Filipino studies and the broader field of critical ethnic studies? I don’t think there’s not a lot of depth to those conversations.

MT Vallarta: Thank you Jason! My understanding of a critical ethnic studies practice is one committed not just to interdisciplinary work but also to anti-disciplinary formation. I think particularly of the work of Audre Lorde and how multidisciplinary her work was, how much of a hybrid writer, hybrid scholar, community organizer, and intellectual she was. How her identity as a queer, Black, disabled woman demonstrated critical approaches to intersectionality that were anti-racist, anti-imperial, and anti-heteronormative at its core. To me, that’s the intention I ground my poetry in, especially as a Filipinx studies scholar.

For me, Filipinx studies has always been a poetic project as much as an intellectual one. I’m thinking about how the nation state of the Philippines wouldn't even exist if it wasn't for poets like Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, and Leona Florentina, who were writing poetry that produced freedom, dreams about nationhood and Filipino thought and ontology, how those freedom dreams continued on across the diaspora into the present. Emergence of a Filipinx diaspora poetics really exploded in the nineties, and 2000s with Eileen Tabios, Barbara Jane Reyes, and Maningning Miclat.

My poetry is also steeped in queerness as a political project, something fundamental not just to transformative justice but also to anti-racist and anti-imperial exercises in Filipinx diaspora formations. I’m also thinking about how Filipinx America, as a project, has always been queer to the U.S nation-state: deviant, aberrant, and a racial Other across U.S history. I want to demonstrate how writers have always written against that.

Jason, your book thinks about critical solidarities for immigrant and refugee communities, and across social justice and transformative justice movements, and I want to ask how your book shifts this critical moment.

Our language will always fail at fully capturing,

as all languages do.

JMP: I really appreciate your mentioning of Audre Lorde and thinking about her work and critical ethnic studies.

I think there was a moment in Critical Ethnic Studies that was challenged by queer color critique which, in my understanding, points to that generation of writers and thinkers like the Combahee River Collective and the nuances of intersectionality, before the term was coined. Critical ethnic studies has attended to the questions of queer color critique by going back to think about its insights. There’s been a multitude of forms and genres and less rigidity, like Gloria Anzaldúa's Borderlands / La Frontera; and This Bridge Called My Back is an anthology, but also a work that holds so much, in terms of critique, debates around solidarity, but also form: letters, manifestos, diary entries, poems. Citation of Audre Lorde, and that generation of queer women of color writers and thinkers really opened up possibilities for knowledge we can produce and what the text could look like.

I think the book as both a reading exercise and as a composition is attentive to solidarity through an interrogation of relationality, how our many histories and our many historical presents are entangled and provide the conditions for building together. I often go back to that 1995 interview between Angela Davis and Lisa Lowe in which Angela Davis describes women of color feminisms and the potential of identity politics as not in the development of politics based on identity, but instead in a development of identity based on politics. So, with the book, I want to think about how commitment to liberation struggles are at the core of our identities.

MTV: Your mention of Anzaldúa brought something to mind. Specifically page 105 of I ask about what falls away that begins with “Some poets pretend a non rhetoric to let language do its own work and in such pretending, these poetics remove poetics as a work doing work in the form.” I have been preoccupied by these lines! What does it mean to let language do its work, or let form do its work in relation to the different forms that these women of color scholars and feminists have given us to work with?

I’m also thinking about the words “work” and “labor.” The labor of cultural producers, role of language, the dominance of work and work culture in the lives of people of color. And what role poetry has in that contestation and poetics as a type of work/labor?

Non-narrative spaces are spaces of refusal.

JMP: Yes! I’m going to move to that question. My work is situated in different places. I came out of performance and spoken word and that had its own genealogy of radical Asian American organizers committed to the notion of cultural work. I was trying to figure out my own identity and who I was as a writer. In coming out of those spaces in the early 2000s, like I Was Born With Two Tongues and Yellow Rage–these folks opened up worlds for me. Think, like the commitment to liberation.They opened up a form of consciousness, a pedagogy that was always there, so for me, critical ethnic studies has always been a historiographical project and a way to reclaim or reacquaint ourselves with those political energies. I ask about what falls away is situated in critical ethnic studies, first and foremost, in that project of solidarity. There’s also these different riffs of sadness.

MTV: Yes.

JMP: I write “Such sadness is a relational urgency.” The attention to relationality has always been central to understanding what I’m trying to offer…thinking about the form women of color like Audre Lorde offer, and Jen Soriano, too, writes about intersectional form. I find writing on form fascinating because it affords us spaces for movement. Like we can employ a form or abandon it and it's kind of like disciplinary and anti-disciplinary formations. So I guess my work is theoretically, politically, within those conversations around optimistic relationality. It’s a young inquiry to think about the political project of Filipinos, Filipinx, Filipinas, right? I am very interested in those conversations as a movement towards solidarity.

Like in the Philippines when a protestor took a knee to protest the anti-terror law, that was an amazing gesture. When I mention “I ask of your tenderness” I’m talking about the protests. Like during COVID there was a caravan protest where they moved across different sites where Black women were killed and they had someone narrating live on Facebook on what happened. As the caravan moved, we also saw Filipino organizers—and it made me realize that we have to recognize our struggles as connected. I think my poems are also interested in giving language to political solidarity.

MTV: To read your poem and to be taken into that temporality and bear witness to your language was an amazing experience that remains embodied in your book. It’s so important to maintain critical gestures of solidarity. On relationality, that collective sadness we share across transformative justice movements is what sustains me as a poet, scholar, and organizing. Being real about these emotions is powerful. There’s power in harnessing that political grief; Audre Lorde uses anger as a way to highlight the importance of continuing to build.

anti-racist, anti-imperial, and anti-heteronormative:

To me, that’s the intention I ground my poetry in,

especially as a Filipinx studies scholar.

JMB: Right, not to interchange sadness and grief, but there’s a moment on page 33 where the speaker says, “my mother is giving new epistemology to illness.” There’s this transgenerational trauma and making sense of mental health in that moment, but I also wanted to interrogate an alternative epistemology of sadness and grief.

Certainly we've seen folks write about things like melancholia as sites of political possibility. Grief is layered. I’m starting to think that maybe my book is an extension of Neferti Tadiar’s Things Fall Away. I wonder if the affinity is found in the grief, if the grief is the space under which we gather and sort of make sense of one another, and care and and figure out how to care for one another, or, if it's the lower- case grief that falls away from like Western notions of Grief. You quoted Jack Halberstam's queer art of failure, so thinking of failure of the project of the neoliberal machine so it calls us to other logics.

You mentioned earlier about being real about emotions of sadness, grief, and depression—you didn’t use that word—but internal struggles and moving past Western frameworks. I wanted to ask about how to resignify grief and sadness or disarticulate sadness and grief from complete loss. I referenced, my cousin, one of my aunties, one of my mentors, there was a lot of loss that happened in the moment of composing this book. There’s a point in your book where you write “the Filipino diaspora is a transpacific current of chronic sickness.”

MTV: In many ways I’m still reflecting on that statement. I was thinking a lot about intergenerational trauma and how it has made my family and people across generationals physically and mentally ill, and disconnected from their mind bodies to the point it begins to affect and fracture their relationships and relationality with each other.

It also helped me understand where my parents were coming from, how that act of migration produced a sense of shared grief that my parents never fully recovered from and have passed down to my sisters and me. That grief does make us sick and push that relational urgency to understand where that where that pain is coming from and connect it to the larger institutional and systemic violences that have produced the displacement, commoditized and objectified labor that have led to dispersal of Filipino workers and families across the globe, and to think about how to be more compassionate with ourselves and others.

I see resonances of that in your book, particularly in the long poem, “Here, inside of this sentence,” this story of a man who turns into a fish who is made of ghosts and flesh and bone, and how that in itself produces a way to think about how to gather and organize and reflect on grief as sadness through different forms. There are so many different forms in I ask what falls away. To me that sentence poem—is it okay that I call it that?—accomplishes a certain type of metamorphosis and relationality that is fundamental to that form of the sentence.

Being real about these emotions is powerful.

There’s power in harnessing political grief.

JMP: Right, I think there’s a way to think about grief that does not foreclose possibility but also I do not want to romanticize or fetishize grief or sadness. I guess to continue to develop alternative epistemologies of grief and sadness. There’s this theoretical political work that we’re both trying to do. The political project is shared.

When my father’s brother passed away in the Philippines, my father didn’t have space and time to grieve for him properly. It was the first fully realized section I wrote for this book. In terms of sort of offering a love letter to a specific geography in San Diego, which is the neighborhood of Mira Mesa, where I spent a lot of my adult years as an educator and student. My partner and I say we left a part of our hearts in Mira Mesa, and I wanted Mira Mesa to be part of literature, so it was gonna happen some way. There’s a place in Mira Mesa, called Good Shepherd—the priest said we mourn people, but we also mourn places. So there’s a mourning of changes in Mira Mesa and my uncle—his life as a laborer, you know, his life as an uncle, as a father.

At the moment, I was thinking there’s a thing called a sentence. What can it hold? Can it hold all this? Can it hold grief? Can it hold all the possibilities? Can it hold the genres of fiction and memoir? Can it hold various realities?

MTV: Thank you so much, and I was wondering if you could also talk more about the process of what it was like to write this sentence poem. And how? When did you realize that it was finished, and that you were able to really illustrate just how much a sentence could hold, and also how much also falls away by working with just a single sentence?

JMP I asked myself: what would the sentence hold? And again, what would fall away? What would I have to sacrifice? What would not make it? But also, what does it mean just to write in all the excess in there? What if I just caught a bunch of commas? What if there were clauses that looped and referenced back? You create a universe. Initially, It was just one sentence on a word doc, but I didn’t want the story to end. I was trying to play with constraint, like that figure was gonna go back home, no matter what. Going back to what you said about Transpacific current, maybe a sentence can’t hold that. Our language will always fail at fully capturing, as all languages do. I think of a sentence as a unit of narrative, it could hold so much and never be right.

I kept on adding on; it went from like 500 words. Then the next time I had a reading, 550 words, and the next time I had a reading, 600 words. So I had the narrative. I knew that the subject was gonna turn into a fish, then I expanded on that moment. What is a ghost? Then that moment came. It was just that lakay, or remember himself as lakay. And then all these other languages came about. Markers of kinship and things like that. So those things started and like, I felt like, oh, let me just layer, layer and layer and see what happens.

MTV: It also reminds me of remaindered language. You’re playing with the excess of a sentence—with how much a sentence can hold and not hold at the same time. Reminds me of José García Villa’s comma poems and how he was also playing with the sentence and clauses. The sentence itself moves as a type of current, is a wave, too.

we mourn people, but we also mourn places

JMP: You could probably take each section of the poem, but that section, like what falls away from the constraints of the sentence is the rest of the poem. Language is also a part of that particular narrative.

My last thought is writing against the idea of accumulation and what that means to have writing as an anticipatory space. In writing I asked about what falls away, I knew I had to write about the homie, my cousin, my uncle, the late Susan Quimpo. This was how it was gonna happen.

Non-narrative spaces are spaces of refusal. There’s a vulnerability I’m not willing to give up. I wanted to invite you to think about the act of refusal and the act of remembering. I wanted to see how you negotiate that space when writing about queer death and futurity wrapped in the same potentialities.

MTV: There were poems that were a lot more raw and, I guess, more revealing, that I ultimately decided to not include in the manuscript, because, like you said, I was wrestling with that decision to reveal and conceal. I wanted to respect the people I was writing about. I had conversations about how they were being represented in the manuscript, and I got my sister’s blessing to write about her story, and I don’t think that poem would have turned into that lyric essay if my sister wasn’t generous enough to share her story with me. Being vulnerable was a way to really give justice to the work, to the folks that I wanted to write about.

What are you working on right now?

MTV: I am currently working on a small manuscript of poems about surviving my academic year of Fall 2021 - Spring 2023, when I lost two loved ones to suicide. I am also working on the manuscript of my research monograph, Dismantle Me: Queer, Mad, and Anti-Imperialist Filipinx Poetry, that examines the anti-imperialist aesthetics stewarded by contemporary queer, trans, mad, and disabled Filipinx poets. How about you?

JMP: I’m returning to a set of experimental essays that I think will try to understand my mother’s history. I have this failed novel about U.S. vs. Narciso and Perez, a 1970s court case in which two Filipina nurses, one of whom happens to be my mother, were framed by the FBI for murder, poisoning, and conspiracy. I’m at the point of letting go of the whole impulse to write a narrative history and I’m really hoping to open that up with what I’ve learned writing I ask about what falls away.

MTV: Thank you so much for everything, Jason! I am thankful to be in community with you, in poetry, academia, and friendship. Please take care and excited to share space with you again in the future!

JMP: Thank you thank you, MT! I’m so honored to be able to think with you in this way and in future ways!

___________________

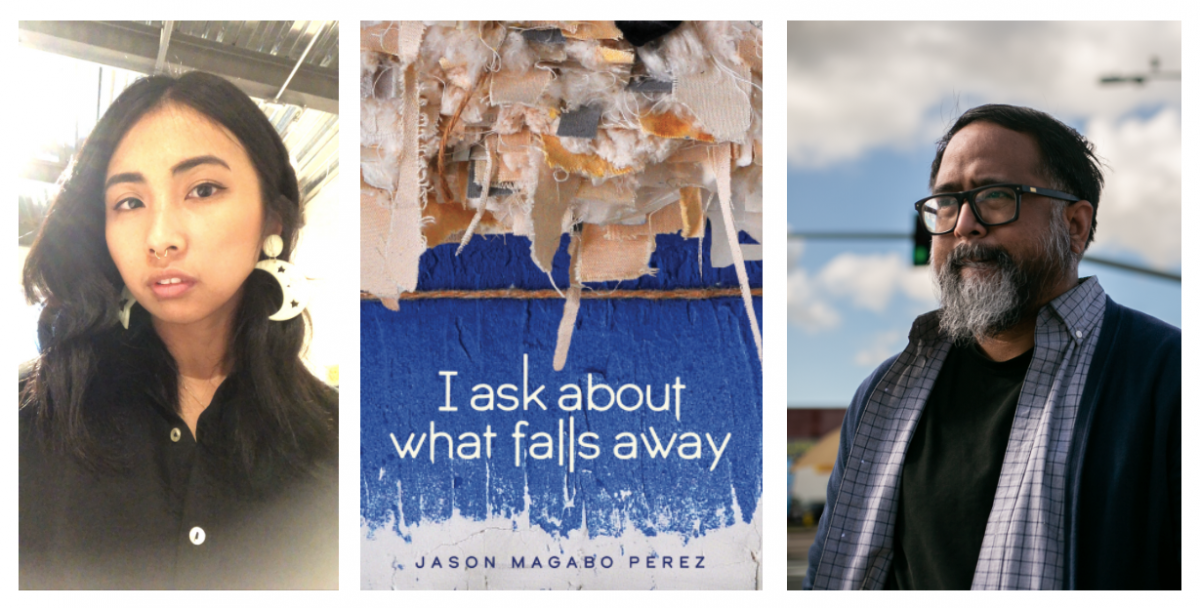

Jason Magabo Perez serves as San Diego Poet Laureate 2023-24. Perez is the author of Phenomenology of Superhero (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2016), This is for the mostless (WordTech Editions, 2017), and I ask about what falls away (Kaya Press, 2024). Blending poetry, prose, performance, film/video, and oral history, Perez’s body of work explores anti-colonial Filipino American historiographies, intimacies, and solidarities. Perez is an Associate Professor of Ethnic Studies at California State University San Marcos.

MT Vallarta (they/them) is a queer, non-binary, disabled, Filipinx poet. They are an Assistant Professor of Ethnic Studies at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, where they teach classes rooted in anti-imperialism, queer of color critique, disability justice, and creative expression. They are hard at work on a research monograph titled, Dismantle Me: Queer, Mad, and Anti-Imperialist Filipinx Poetry, that explores the radical tradition of Filipinx poetry written by artists who are queer, trans, mad, and/or disabled.