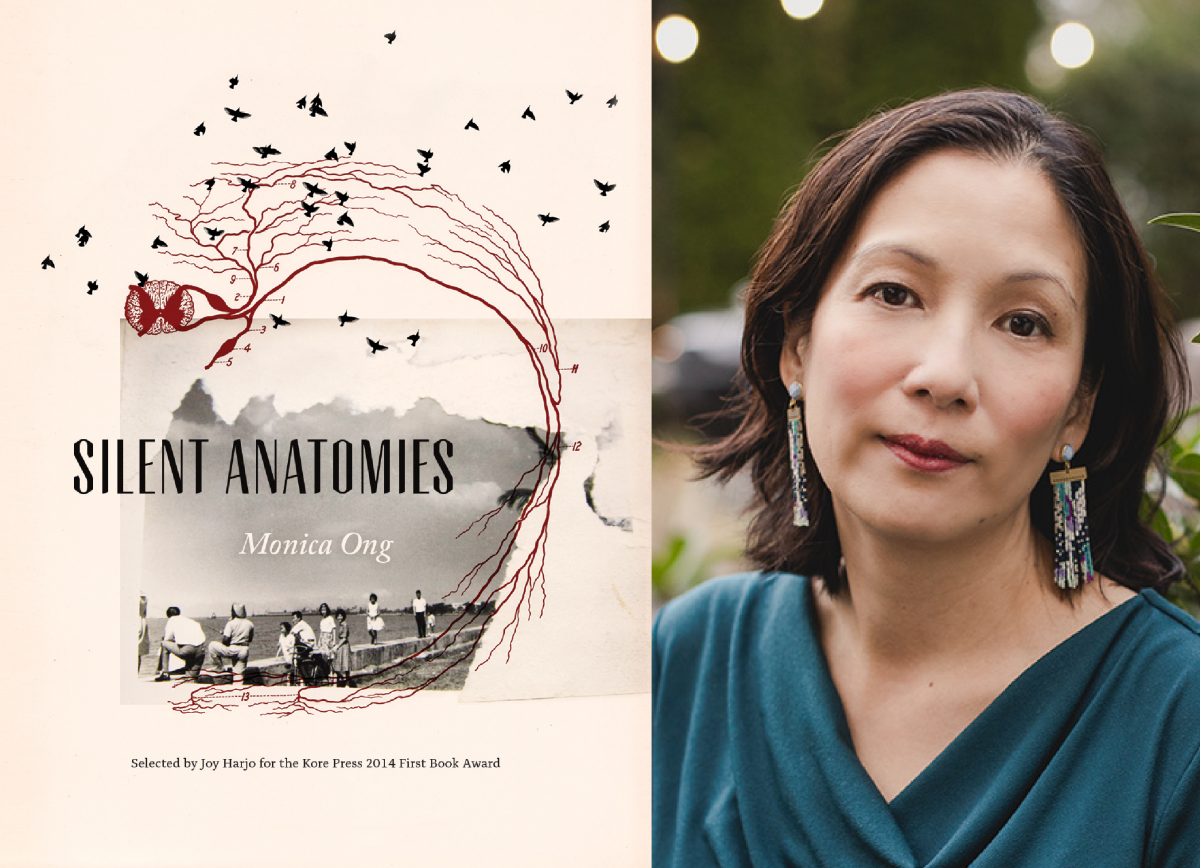

Monica Ong is a visual poet weaving together design, visual arts, language, text, and technology. She is the author of the visual poetry book Silent Anatomies. Planetaria, her most recent exhibition of astronomy-inspired visual poetry was on exhibit at the Poetry Foundation in Chicago in 2022 and featured at the Hunterdon Art Museum in 2023. In 2024, she was named a United States Artists Fellow. After spending time with her book Silent Anatomies, I was curious about the processes behind her art. We met over Zoom to talk about visual poetry, layers of language, and the process of experimentation.

_______________

Amy Smith: You are a visual poet, working at this intersection of text, image, digital media, research, family history, all the things. I'm curious how this process started for you. Have you always felt like a poet or an artist? Did one come first or did they develop together?

Monica Ong: That's such a great question. I think as a younger student, you’re often told that you have to pick a major or pick a lane. I struggled with that. I was always doing art and interested in literature and felt reluctant to pick just one, because it meant letting go of the other. I think I got used to occupying both mindsets simultaneously, because growing up the daughter of immigrants I felt like I was doing a lot of translation all the time anyway, translating both language and culture.

Because I found a natural ease with the visual arts, I started there as an art major. But between art school and grad school you spend a lot of time in cultural narratives and different forms of writing. So when I was setting off to grad school, I got accepted to both an MFA writing program and an arts program. And I was like, oh, no! What do I do? And so I chose digital media as a way of working that allowed me to occupy both the visual and the literary together. I'm glad I did.

I came out of grad school as a designer, which is so nice. Because you're thinking about everything from typography to the production of the poem as a printed piece, or an object, or a space. Having a design skill set allows me to really think about the experience I'm trying to design for my visitor, and all the ways I can make it feel as intimate and immersive as possible. I've always felt such a joy of engaging with language, but also thinking about language from a design perspective, and how language and image work together.

AS: Can you speak to your process of bringing language and image together in a piece of art?

MO: When I think about what I make and how I make— sometimes there is a visual trigger. For example, I'm the daughter of a physician. So I was looking through my father's old medical books, or I'd go to a flea market, and I'm looking at really interesting vintage objects, sometimes I'll have an instinct that says: Oh, I would love to see this as a poem.

Or at the same time, there are poets that I read where I notice the language or the use of language, or something about the typography or the syntax, that when I read them I need to write for an hour, because that's how inspired they make me feel. So sometimes it starts with the language and the narrative. There are things in the language––because language inherently also contains images–– that I'll start associating with what I'm writing, and then I'll take those notes and images, and I'll just start diving into interesting resources for visual materials.

You can see in both Silent Anatomies and Planetaria, I spend a lot of time with public domain resources like old medical textbooks, or astronomy textbooks, or things like that, because the visual material is really rich. It's also easily available to play with. I spent quite a lot of my design career in spaces of information design and data design as well. So there's something about language in terms of cognitive design too, where it's not the letters that convey but it's the relationship between elements, like the visual intensity, the visual density, the use of contrast, or the use of blank space as another kind of syntax.

AS: It is fascinating to think about meaning on all these different levels.

MO: We understand visual language in things we look at like the medicine bottle, or legal forms, or star charts. They come with a context. They come with a particular history, and they come with a particular set of power dynamics and audiences, as well as some assumptions about the authority of the document, or the truth or fiction of a document based on what the form looks like. So that's the design. You can play with that. You can invert that. Medical documents and ephemera exude a kind of authority or factualness, right? But often our memory about things is very porous. Sometimes it's a little more fictional than factual. Or maybe there are things that color our perspectives that don't make it fully objective. So I think those tensions working together are able to make the words that you read rise up with a little bit more sharpness, or maybe make you question your position as a reader. I think a lot about those things. And again, I owe that to just being a designer.

AS: There is so much in what you've said here, and so many directions we could go. But I am thinking of what you said in an interview in BOMB magazine: “I like to think that hybrid practice equips us to live beyond binary thinking. What emerges when working ‘between’ disparate polarities is that 3rd space, something broader and more generous, that aspires toward a design that can hold us all.” I love this idea of the 3rd space. Your poetry is imagery rich, and can easily stand alone, and your art pieces also can stand alone. And then you bring them together in a way that creates that 3rd space. It is not easily defined yet is full of meaning. I wonder if there's anything more you want to say about that?

MO: First, thank you so much. I’m one of those artists who works in my little basement studio, and I'm always like, well, if anyone sees this work and enjoys it, that's great. But just to hear how much it opens up people's processes is very satisfying.

If I were to think about what phrase expresses how I work, I often borrow from the improv artists who always say: “Yes, and.” We live in this strangely binary world. Are you this or that? And if you're this, then you must not be that. It is kind of frustrating, because I feel like we're not. We can't simplify people.

AS: Right, we are so much more complex.

MO: Yeah, exactly. And when we think about process, if we have a “yes, and” attitude, then we aren't so focused on the constraints. Instead, our focus is more on the possibility, right? It's like, I haven't figured this out yet but I have these elements. I'm not sure what's going to happen. I might have a couple of elements, and then a question, and then nothing else is planned. It's about the spirit of experimentation. I'm not going to know unless I try.

The “yes, and” part for me preserves a space of play, experimentation, and (god forbid!) some fun. Try to make sure you have fun creating. Because why would we go to so much trouble if we didn't try to at least have a little bit of fun? I think it allows me to shed those fears of: oh, if I do this, it's not going to be poetry, or if I do this, it may not work in art. Instead, to just be able to say: let's not think about that right now, let's not worry about that for the moment. Let's just see if we can ask a question and have a really fun exploration of that question and see what happens.

AS: I love this idea of living in the question. Artists have so much to offer in this way. There’s so much happening in the world, and art is the thing that comes in with questions and says, well, what if? What else can be? How else can we be? This makes me think about the stories in your work. Joy Harjo, who selected Silent Anatomies for the Kore Press First Book Award in Poetry, talks about stories as being the purpose of humans. We are stories, we tell stories, we share stories. The stories in your work bring together ancestry and current issues and cultural commentary. So I wonder, do you think that telling these stories contributes to a kind of healing not only for who is here now, but for your ancestry? Is there a collapsing of time inherent in art where future generations can carry forward the healing for older generations? And what is the impact of these stories on younger generations?

MO: Yeah, that's great. I love what you're asking, because as an artist we start by making work because we have a personal question. But to me ultimately it is a conversation with the self and others. Whether it’s with your community, or between generations. I always thought of art as a way to make offerings. Growing up in a Buddhist tradition, there’s this idea that we're here to create offerings that enrich the lives of those around us and help us grow. There is a saying that when you make these good causes it increases your fortune seven generations forward and seven generations backwards. Which is to say that a lot of the artwork that I create came out of observing and experiencing struggle.

One of my aunties really struggled with her mental health, and I felt like she was one of the ghosts writing with me in Silent Anatomies. She was somebody that they wouldn't speak about in the family. Making this work was a way of remembering her. I’m grateful for her because she played such a huge role in these conversations about culture and mental health, being able to break that kind of stigma in families and to openly talk about these things. So to me, art has that quality that when there are challenges and difficulties or tough experiences, it has a way of transforming them into a catalyst for other connections and ways of coming together that create value.

I hope that, looking back, it's actually been able to elevate what she's done for the family. That's kind of how I think about it. That when we do what we can to create conversations, we are able to elevate, or at least give a person’s memory a better home.

AS: Oh, I love that. That's a great way to say it: "to give memory a better home.” There is so much I'd love to ask, but let’s finish with one more question. What are you working on now? Any current projects that you want to talk about, any new directions?

MO: Yes. I am excited because I'm partnering with the Yale Quantum Institute to adapt Planetaria to a planetarium reading. I've never designed for a planetarium before. This opportunity came up to create an immersive experience of poetry where we can, with the help of an astronomer, position folks near the different Chinese constellations that inspired the poems that they will hear. This again brings in my ancestors and the imagery from the work. And you know, it's so funny because in a sense, stars are ghosts as well. What we see of stars is really just the light that they emit from many years ago. In that sense, these different ghosts gathering together with audiences is an interesting space to think about. It's a way of experimenting–– what does it mean to create a really meaningful poetry reading in this non-conventional setting?

AS: That sounds amazing!

MO: Yes, so that's exciting. We're planning that for March in 2025, and then also next spring is hopefully when I'll be ready to release Planetaria as a publication as well.

AS: Oh that’s great! I was going to ask if that might become a publication.

MO: I'm really excited about it. A few years ago, I founded a micro press of visual poetry called Proxima Vera. I had success bringing editioned fine press visual poetry to enthusiastic readers and collections. I've been learning the ropes and more recently have been developing a process for what it means to publish visual poetry. Using the practices that I've learned as a designer, but also as someone who asks what it means to design a meaningful reading experience that brings all these different aspects into a gorgeous publication. I've been moving pretty slowly, but we're getting to the home stretch. So that's coming this spring as well.

AS: That's exciting! I can’t wait to see the final publication. Monica, this has been such a great conversation. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today about your creative process.

MO: Yeah, yeah, I am happy to do it. I’m grateful that you are taking the time to spend with this work. So thank you!

______

Monica Ong is a visual poet and the author of Silent Anatomies (Kore Press, 2015). A graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, Ong brings a designer’s eye to experimental writing with her hybrid image-poems and installations that surface hidden narratives of women and diaspora. Her poetry can be found in Scientific American, ctrl+v, and Poetry Magazine, and most recently in the anthology A Mouth Holds Many Things: A De-Canon Hybrid-Literary Collection (Fonograf Editions, 2024).

Ong's visual poetry has been exhibited in galleries nationwide including New York’s Center for Book Arts, the Hunterdon Art Museum, and the Poetry Foundation. You can find her fine press visual poetry editions and literary art objects in over fifty distinguished institutional collections worldwide. In 2024, Ong was named a United States Artists Fellow.

Amy Smith is a poet living and writing in Northern Nevada. Some of her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in several places, including: Humana Obscura, Gyroscope Review, contemporary haibun online, and the Wee Sparrow Water Anthology. She published her first poetry collection, Composting the Moon, in March 2022. Amy is currently pursuing her MFA degree in poetry through the low-residency program at the University of Nevada, Reno at Lake Tahoe.