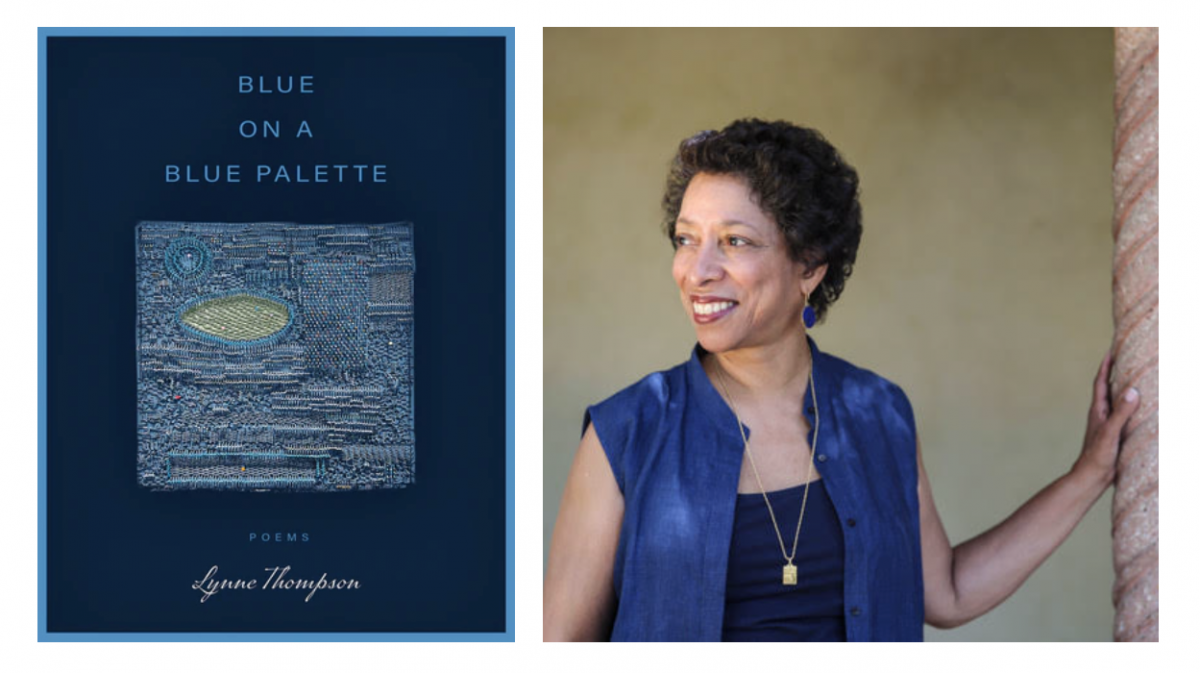

Lynne Thompson’s fourth book, Blue on a Blue Palette, reads like a master class in how to put together a collection. Using visual art as its central metaphor, the book blends retablos, the enslaved rebellion on Berbice, store-room sex, the Pandemic, aging, Breonna Taylor, Elizabeth Short, and Joni Mitchell into a seamless whole. Thompson accomplishes this with virtuosic forms: footnote poems, centos, free verse, and a form she believes she invented: centoums. The book highlights the shades of women’s lives–sometimes joyful, sometimes dirgeful, always against a background of blue. I was taken by the range of subjects in this finely-wrought collection, and by the amount of research that went into the book, so Lynne and I met over Zoom to discuss it.

______________

Laura Wetherington: We worked together in UNR Tahoe’s low residency MFA program. When Matt Franks and Patrick Hicks gave talks on their work, I asked something about research. You came up afterward and said that we should talk. So I'm really glad to be here with you now and able to ask you about what research you've done in your poetry writing. You've published four books, which means that you've had a lot of time to really kind of stretch and grow. So can you talk a little bit about the evolution of your research process?

Lynne Thompson: As you asked me that, I'm thinking of a poem in my first book, The Van Dyck which was kind of a falling into research that I hadn't planned. My parents came to the U.S. from the West Indies and they came separately through Ellis Island. The Ellis Island records are all digitized, so if you know the name of your grandfather or great grandmother or whatever and they came through Ellis Island, you can find their records. In the case of my dad, among the many records, they had a record about the ship. They knew the name of the ship, so I started to just kind of do a little research into when it sailed and where it sailed from. It turned out that this ship would travel between South America, Barbados and New York every two weeks. It did that for five years before it was decommissioned. World War Two broke out and it was recommissioned. It turns out its first assignment was to evacuate the Jews in Narvik, Norway. The Nazis found out about it, torpedoed the ship, and to the best of my knowledge, that ship is still at the bottom of the sea. The reason we know that is because they had a hearing in the London courts. That's how I found out the information and I was able to write the poem from that bombing backwards to when it picked up my dad in Barbados. But that was all because the information was available, I just had to dig for it. So that really kind of propelled me into recognizing how valuable little snippets of information accessed through research can be.

LW: Do you feel like there's been an evolution from your first book and you are doing something different now or...?

LT: I still like to fall into things. I often don't plan specifically, but maybe I have a kernel of an idea and then I start Googling and reading and that just pulls me through, like a thread. I wouldn't say the process has changed necessarily, although I've learned new tools and new ways to do the research and the writing. But I think part of it is being a lawyer by training that makes me want to dig into the facts and ask, how do I make it fit together? I think those two concepts dovetail to make a poem.

I have a kernel of an idea and then I start Googling

and reading and that just pulls me through, like a thread.

LW: Can you say a little bit more about your legal training and how that has prepared you to write poems?

LT: Yeah. I mean, there’s a difference. A lawyer tries to persuade, whereas a poet is really trying to dig into your emotions and not necessarily persuade you, but to present something that's going to impact you emotionally. But they're both about language; they're both about the best words in the best order. They're both about telling a story, whether you're a criminal attorney or you're a corporate attorney, or if you're a litigator, which I was. You're trying to tell the most convincing or the most effective story: the most convincing if you're a lawyer and the most affecting if you're a poet.

I was just looking at an exercise, as a matter of fact, that I got from the amazing Ellen Bass. She was talking about word lists and how that takes you down a rabbit hole into your own poem. And she was saying that she was doing a word search in Brigit Pegeen Kelly's book, The Orchard. And she found dragon, heaven, split, honey, swollen and those took her off into her own poem.

In both areas, law and poetry, which have no other synergy perhaps, they have the basic synergy that they're both about language.

LW: Moving from litigating to painting, I think about the title of your most recent book, Blue on a Blue Palette, and how it hints at ekphrasis. How did you make your way to this through-line for the book and can you say something about how the title works as a kind of operating principle for what's inside?

LT: A friend of mine said while I was Poet Laureate of Los Angeles and not writing as much, “This is a good time for you to put together a book if you have enough poems.” And I had a big stack of poems that I thought could be book-worthy, but they weren't written as a book. One of the things I noticed as I went through them was how often either the Blues or the color blue was referenced in the poems. I was a little surprised. Blue’s not necessarily a favorite color of mine. And so that was balanced against the fact that a lot of the poems were about women. Their rage, their joys, their sexuality, their aging, their religious and spiritual feelings, all of that was kind of arrayed on this blue palette. I am totally title-challenged, but this just came to me.

LW: ‘Title-challenged’? I mean, it's hard to imagine that by looking at the table of contents.

LT: Well, maybe I'm learning over time. You can teach an old dog new tricks. My first book was originally titled The Open Hydrangea Box. And my editor at Perugia said, “But what does it mean?” And I said, “Well, I don't know, but isn't it lovely?” She said, “OK, lovely. But you know, it's got to fit somehow.” So it is something that I give a lot of thought to because I do feel a little insecure about titles. But thank you for that compliment because I do struggle with it.

LW: Well, maybe that struggle means you're putting a lot of attention into it. It shows. But also I'm the kind of person who would read a poem called Open Hydrangea Box and think “That's beautiful. I don't know what it means, but I love it.”

LT: Yeah, that's what I was hoping I could get away with. It ended up being Beg No Pardon, which actually for the collection is a much better title.

LW: I'm thinking about the notes section in the back of Blue on a Blue Palette and how it’s a reading list. I mean Ai, Ruth Stone, Kwame Dawes. Is reading poetry a form of research to you? Do you think about it that way?

LT: I haven't until now. But now I will give that some consideration. When I do workshops, I say: “You know, the days when you feel like you're not writing? If you're reading, you're contributing to your writing process.” So I like to read as broadly as possible: science, recipe books, anything kind of out of my wheelhouse, but I read widely, especially for the language that I can get from it, that's going to really deepen the poem’s meaning.

One of the poems you'll notice in here uses the phrase Stephanotis floribunda to refer to flowers and I wouldn't have known that, but I had a book with all these Latin terms for flowers and I thought, OK, there's got to be something in here. Reading is crucial on many levels that can feed your own work. And also with poetry, what are other poets doing out there? What's occupying people's thoughts? To me if you fail to do that, you miss an opportunity to deepen your own work. And you may not read what I want to read, but you’ve got to read something.

LW: That's right.

LT: So I do consider that part of the process, because I like finding little kernels of facts and going down that rabbit hole to see, is this something I can use in some way? Maybe I’ll throw out 80% of it, but that 20%, man, it can be so, so rich.

Oh, and the other part is that this is a book where I wanted to honor and highlight people like Kwame and Ai, my literary forebearers. In the case of “Assemblage", which is honoring the artist Betye Saar, I mean, she's just a heroine. The woman is 95 and she is still working in the studio. I think that persistence is a crucial part of the creative process.

LW: Do you feel like there are people in Blue on a Blue Palette that a reader would not see? Like, either influences or references that are not in the notes, but like, here's somebody who's really deeply influenced this?

LT: Yeah, I mean, either would not see or perhaps have forgotten. That's why I wanted to do the Joni Mitchell poem because I have a lot of nieces and nephews under 40, and they're like, “who is this Joni Mitchell person?” I'm in my head, I'm thinking, “How could you not know that?” But they’ve got their own people and their own music, and that's fine. But I want to just put a little kernel there for them, just a little nugget that if they're curious enough, they'll go and say, “OK, yeah, I know those songs. I've heard them but I didn't know she was the person,” right?

So, to highlight, to honor, to just feel like I'm in an actual conversation, with Terrence Hayes and Diane Seuss by writing a cento incorporating lines from their work. I purposely didn't want to do a sonnet because the two of them are like the reigning king and queen of the American sonnet, right? So I came up with essentially a form that I'm calling a centoum because it's a cento in a pantoum form, which was my way of saying, “Let's invent something new” in the way that they invented something new.

LW: Yeah, I love that. I love that! And I think there are so many forms in this book. Pantoums, villanelles, centos, but also just the form of the perfectly shaped tercet that runs the page, or the couplets. And rhetorically we could think about anaphora or call and response. And I wonder if you could talk about when the formal elements develop in your process? The beginning or the end?

LT: It could be both. It has been both. Sometimes I recognize it early on. Sometimes in the revision process I think, “Gee, what if I tried X?” I did purposely want there to be a lot of forms as a metaphor for the many forms in which women present themselves as mother, sister, daughter, doctor, lawyer, minister. I'm not sure it's always as clear, and I'm not sure I was as clear early on, but I just recognized that this was a book where these different forms would fit into the whole I was trying to craft.

LW: Yeah. And is there a connection for you between these forms of women and also the forms of blue or of ekphrasis or the Blues.

LT: Yeah, I think that was why when I found the Cornelius Eady quote, I said, “Oh my God, this is just—this is so perfect. This is exactly what I'm trying to say: ‘Some folks will tell you the Blues is a woman.’ Alright, I'm good.” That's exactly right.

I tried to put joy in where I could, but the fact is that especially now, where many of us feel that women are being undermined, marginalized, physically abused, murdered. Yeah, that's the Blues, you know, that's really the Blues. So, it is a form of ekphrasis I guess, although not for a specific piece in most cases. “Assemblage” is composed of titles of Betye Saars’ work to tell a biography of women. But other than that I don't think there's a specific reference to any piece of work. Actually, that’s not true: “Torch to Shogun” refers to John Bigger’s piece Shotgun, Third Ward, #1.

LW: I want to end by asking a question about research that’s kind of messy, so forgive me, but I’m thinking about the line between fiction and nonfiction because in the three-genre track in an MFA program, these are categories that get pulled apart and siloed. But as a poet, I'm always thinking about the continuum between fiction and nonfiction within poetry. And as I was reading your book, I was thinking about how some of the poems are historically rooted. Right? Like “A Rage in Berbice 1763.” Which is rooted in fact, right? But it's also told from a first-person perspective, from a kind of persona. So there's fact and fiction there.

And then also something like “A Birth Mother Wears a Costume her Daughter Will Never Fit Into” which, I hope that you'll forgive me, but after reading Fretwork I thought of as like—not the facts of it, but the feeling of it—maybe as something autobiographical, but deeply, deeply imagined. So here’s another angle with fact and fiction. And then, you know, there's this other category of poems, I think, which are even more non-fictionally autobiographical, because there's a narrator reflecting on real life events, like the killing of Sandra Bland in “Boketto.” So I guess I'm wondering how you think about fiction and non-fiction operating in your poetry and how that connects to research.

I wanted to give those women a voice,

and I couldn't figure out how to do it

without putting an “I” in the middle of it.

LT: I think the great thing about poetry, and maybe why I gravitate to it as I do, is that you can take something like the events depicted in “A Rage on Berbice, 1763'' that was based on a book called Blood on the River, about the actual slave rebellion on Berbice, now Guyana. The book was written by a Dutch woman who found records in a library in Amsterdam. I had never heard of this, and so many people have said, “Lynne, how did you find out? I said, “I found out because she found out”—about this slave rebellion that went on for over a year, and she had this one sentence that stood out that was the genesis of the poem: “While the great majority of leaders were male, a few female counselors exerted crucial leadership early on in the rebellion.”

And so even though this story that I'm telling in this poem isn't specifically described in the book, I wanted to give those women a voice, and I couldn't figure out how to do it without putting an “I” in the middle of it so that readers could be there with those women and what they experienced, and to realize those women produced the generations that are telling you this story today. So that was one poem where it was very clearly based on her research and that one sentence. With respect to the birth mother poem, I am always trying to figure out a way to talk about the family in ways that are not so specific so that the reader can identify with the poem’s themes.

“Boketto” was very much born of a need to say the name of people who have been murdered by the police, particularly women. I never bought the story that this woman who was on her way to a new job, got stopped by the police, put in jail, and that made her commit suicide. The family was adamant that they didn't believe it—and neither did I. And so I just wanted to say to her and readers: If the police were to stop me, I would never give in to them as I don't believe she gave in, but ultimately paid the price.

And I combined this concern with a word I found in the book Lost in Translation by Ella Frances Sanders which has words like “boketto" that have no corollary in English. Hmm. So I was thinking of Sandra Bland and also thinking, as we all do when we’re writing poetry, “How can I pump this up linguistically” and I've always liked that word. I think it's fabulous, and then to give it the weight of saying, “If you're doing this while you're black, you might have a problem. You're just bopping down the street. What the heck, you know, OK, give me a ticket. Because the police officer said she didn't signal. OK, that's a ticket. How do I end up in jail?”

Also, this poem reflects the early influence of Natasha Tretheway, i.e., looking for public histories to intertwine with personal histories. How can we make that juxtaposition so that it broadens how the two histories are understood. Patricia Smith, who's a dear friend of mine, said whatever you want to write about, every poet on the planet wants to write about. George Floyd or January 6th are good examples. How are you gonna find a way into these public concerns that's a little more unique. So rather than writing specifically about Sandra Bland, I put myself in that situation, getting stopped by cops. A judge says, “How do you plead?” And being a lawyer helped.

LW: Well, I think that's one of the beauties of that poem is that everyone's going to know who Sandra Bland is, and so this part of the context is there. And then you're able to kind of go into your own space and it's deeply moving.

LT: Yeah. Ask yourself, what would you do in that situation? How would you respond?

LW: Yeah. I think you’re asking a rhetorical question here, but I also recognize that I don’t have an answer, and I think this is part of what makes your book so deeply engaging. I want to thank you for taking the time to talk to me about Blue on a Blue Palette, which I hope moves into many, many readers' hands.

LT: I'm so honored that you wanted to do it, Laura. I am glad that you found much to like in the book.

_________

Lynne Thompson was the 4th Poet Laureate for the City of Los Angeles. The daughter of Caribbean immigrants, her poetry collections include Beg No Pardon (2007), winner of the Perugia Press Prize and the Great Lakes Colleges Association’s New Writers Award; Start With A Small Guitar (2013), from What Books Press; and Fretwork (2019), winner of the Marsh Hawk Press Poetry Prize, and most recently, Blue on a Blue Palette (2024). A lawyer by training, Thompson sits on the boards of the Los Angeles Review of Books, the Poetry Foundation, and Cave Canem and is the former Chair of the Board of Trustees at Scripps College, her alma mater. She facilitates private workshops, most recently for Beyond Baroque, Poetry By the Sea Conference, Moorpark College Writers Festival, Napa Valley Writers Conference, and Central Coast Writers’ Conference. Thompson is a native of Los Angeles, California, where she resides.

Laura Wetherington is a poet living in Reno, Nevada. She teaches with the International Writers’ Collective and the University of Nevada, Reno at Lake Tahoe Low-Residency MFA. Her latest publication is Little Machines.