Jordan E. Franklin is a Black poet from Brooklyn, NY. An alumna of Brooklyn College, she earned her MFA from Stony Brook Southampton where she served as a Turner Fellow. Her work has appeared in the Southampton Review, Breadcrumbs, easy paradise, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, Frontier, and elsewhere. She is the winner of the 2017 James Hearst Poetry Prize offered by the North American Review, and a finalist of both the 2018 Nightjar Review Poetry Contest, and the 2019 Furious Flower Poetry Prize.

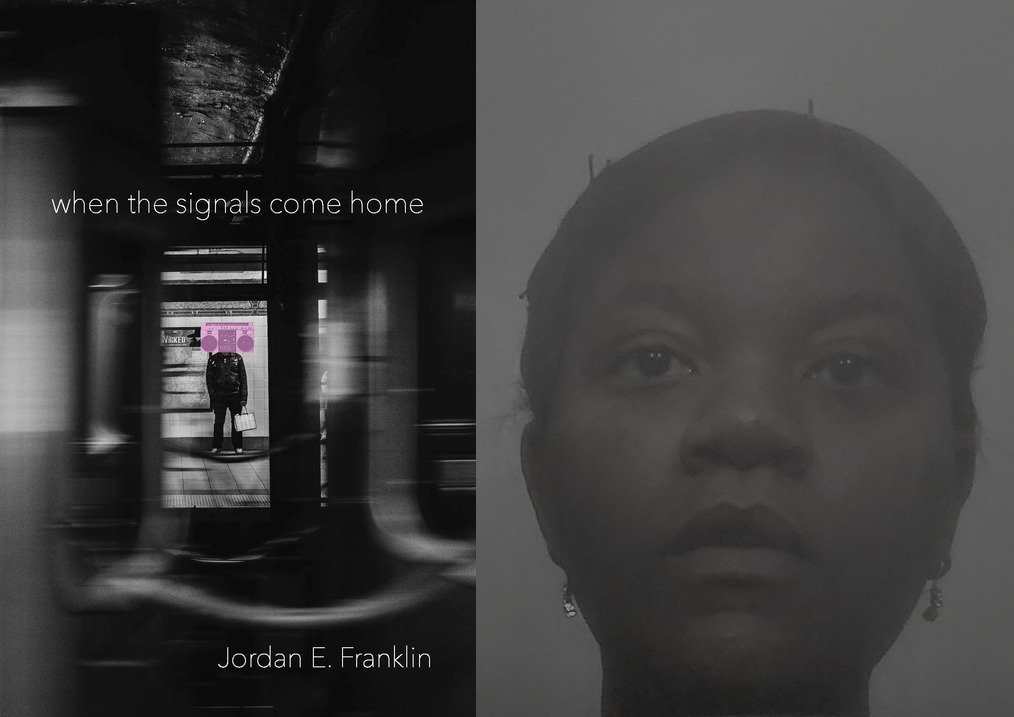

Her first poetry collection, when the signals come home, was selected as the winner of the 2020 Gatewood Prize and will be published by Switchback Books in Spring 2021. Her poetry chapbook, boys in the electric age, is forthcoming from Tolsun Books in August 2021.

Jon Riccio: I did the math, Jordan—you’re one of the poets I’ve known the longest, so it’s doubly wonderful to congratulate you on winning the Gatewood Prize, when the signals come home’s publication slated for March. Prageeta Sharma, this year’s judge, praised your work for its “striking sonorous language,” noting that these are “poems about family narrated with indelible soundtracks, deep building emotion.” We find Duke Ellington sharing the same sectional firmament as a garden that shakes from “nearby rail - / road cars,” while the Mary Jane Girls inhabit a boombox during “a night that redacts the Sun.” The opening lines of your prelude poem, “Inheritance,” situate us in high stakes—

To raconteur tongue,

solar flare temper,

Mom’s cheekbones,

Pop’s weak eyes,

to knuckle-busted hands,

arachnid fingers,

Bible names,

terracotta curves,

to plantations taken,

vows broken,

a potential future: green-

legged and stalling

until the surgeon’s saw,

Central to when the signals come home is your father’s tetraplegia. That we begin with the tongue gives this organ-muscle the most bodily power, a raconteur lens prominent throughout the book.

The healthcare practice of narrative medicine, known as “a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust”[i] has funneled over to creative writing, though your collection transcends this, arriving at what I call Confessional medicine. Your poetry may have inaugurated a new genre (no pressure there)! How might when the signals come home function as a herald of this literary movement?

Jordan E. Franklin: First off, thank you for having me, Jon. I’ll try my hardest not to be a bore!

Second, it is pretty wild thinking about how long we’ve known each other. I met you at a time when I was realizing poetry was becoming less of a hobby and more of an obsession so I’m still in shock that I’m here talking about my own work.

When it comes to the term “Confessional medicine,” I never thought of it as a way to describe my work, yet it fits. I wrote when the signals come home as a way to make sense of what I was feeling and going through at the time. Between my duties/coursework as an MFA student and my duties as a daughter looking after her ill father, there was little time for me to just breathe or process everything except when I was writing. In the book, I am matter-of-fact about my father’s health but I also delve into the conflicted feelings my father inspired in me, both before and during his illness.

When you take care of someone else, you often have to downplay your own needs and put theirs first; this becomes even more jarring when the child is placed in the role of caregiver to a parent with whom they share a complicated dynamic. So, in a way I am confessing.

JR: You feature a quartet of playlists beginning with “Some songs I’m listening to on the way to Dad, Day #,” Van Morrison headphoned with Gil-Scott Heron and Prince. The second installment loses its uppercase (with the exception of Dad) and converts to lines of a poem, “some songs /i’m listening/ to on the way to Dad’s, day #,” David Bowie’s “Lazarus” being the final tune. The music erodes to “/some/ songs /on the way/ to Dad, Day #?” with installment three, its opening act the Cure, back-to-back Jimi Hendrix selections concluding. By the last journey, the split title is “songs, day #,” “to dad’s” falling under R.E.M.’s “the Great Beyond.” The collection is nourished by, and reacts to, these artists. How did a playlist mindset help with drafting and revision?

JF: Before I get to the answer, I want to say I listen to a lot of music; in fact, my only company on my commutes to Dad was my iPod. So, it’s no surprise that music would inform so much of this collection.

When I first approached the book, I had a general idea that it was going to be a family history of sorts. A lot of poems in this draft didn’t make it to the final cut. It wasn’t until I received my last bit of feedback from Natalie Diaz that I realized I had little to no idea about the structure the book would take.

So, I started over.

When I started to see the book as more of an album and less like a book during the second draft, it really opened me up formally and lyrically. I started to play with themes, repetition, sequence, and the form the poems took on the pages. The biggest influences for me at this part of the collection’s conception was the double LP Songs in the Key of Life by Stevie Wonder, the music of David Bowie, particularly the song “The Man Who Sold the World” where his present and past selves confront each other, and Kendrick Lamar’s album good kid, m.A.A.d city.

I got the idea of including the playlist breaks in between sections from this amazing manuscript workshop I took with Shira Erlichman earlier this year. During a critique session of my work, one of my peers, Sana, mentioned that she wished there was a break between caches of poems since there was so much happening in the book. Then, I decided to put a list of songs as a section break. The truth is, the track listing in each of these playlists were songs I actually listened to on the way to visit Dad.

JR: Your pantoum “Recipe” tells us “I built chicken parm on top of Dad’s memory,” memory replacing “old recipe” in the original line. This nuance is heartbreakingly excellent. Any poet can conflate food with family, but you go a step further, years of domestic history revealed in “Between homes, Dad’s army knife opened cans / and memories.” What signals does the pantoum form send in terms of conflict and resolution where your book is concerned?

JF: I wrote that poem last Fall in Patricia Spears Jones’ workshop. Prior to that workshop, I had never written a pantoum before so I’m glad you dig it. I think the reason why I included it in the book (besides how it clearly addresses my family dynamic growing up) is because of its form. The pantoum is all about repetition and creating meaning through the movement/placement of lines. Much like this poem, there is a movement that occurs in the book. Not only am I traveling across New York, I’m also shifting between identities, relationships, and time. You can even see this in the poems that talk to one another; while I am addressing a familiar topic, location, or idea, the perspectives shift. Even in this poem, I am moving between my parents’ houses and foods. This poem is just a microcosm of a larger thing at play.

I think what I’m getting at is that this poem is a reflection of the restlessness and frenetic energy that birthed the book. By the end of both the poem and the book, despite everything, there is no resolution really—just bittersweet acceptance.

JR: Operating from a place of prose, “Find the River” (After Talking Heads) is a three-person origin poem that addresses your father, “dragged and sharpened over whetstone recruitment at the chime of 18. A man in Nicaragua far from home,” your mother, “hummingbirds in her stomach,” and you, “cut from Mom, all Lorca-green and a month late into the new, weary space.” This is also the order in which the paragraph sizes diminish, religious figures Jesus and John the Baptist sharing your entry sentences. What advice do you have for writers crafting a single poem tasked with multiple, pivotal introductions?

JF: My advice is don’t be afraid to draw upon topics, concepts, or ideas you have written about prior even if it is in the same poem. For example, both my parents had a hand in creating me so why can’t the poem be a blending of their origins, kind of like how tributaries meet and flow into a larger river?

When I think about my approach to addressing similar themes across poems or perspectives, I am reminded of something Terrance Hayes once said during a craft talk at Sarah Lawrence’s Summer Seminar for Writers. During the Q&A, I asked him how he went about writing “the Blue Terrance” poems, and he said that he just thinks of topics for poems like a cube in the sense that there is always another side or angle to write about. When he said that, it was like a light rang out in my skull. I felt like he was unconsciously pushing me to complete this project!

JR: “The Hospital” is an extended metaphor of execution—“Dad’s on the Death Row / of the mind, strapped / under the last rites,” you’re “always pleading / for a pardon / that never comes.” Do the poem’s complexities lie more on the side of location or relationship? Are there any poets who influenced your process on poems that take place in medical settings?

JF: I would say the complexities lie in the relationship; in this poem, I was writing about the time my dad was on suicide watch and the moment when I realized that there was a high chance my dad would die without recovering. Up until that poem, we were holding out hope that Dad could possibly recover; even the doctors hinted to such. However, on the day that poem took place, Dad received some very bad news. The truth is, I’m not very fond of that poem because it pulls me back into a space and a feeling I’ve tried to forget.

As for poets who influenced me, I don’t really have any in regards to medical settings. However, I would say Terrance Hayes, Natalie Diaz, and Sylvia Plath are the three poets that influenced the collection: Hayes for his diction and eagerness to experiment with form, Diaz for how she blurs the real and surreal while staying true to her rich, emotional lexicon, and Plath for her candor.

JR: I think everyone should write their own “how to read my poems/” at different points along their trajectory. The fifth stanza, “instead of grief/ say someone rebuilt / your heart wrong,” speaks volumes to mourning as the propane of family dynamics. What prompted your choice of spider, happy, daughter, and sorry as some of the words best left unsaid?

JF: I chose spider because it is already a word or image one can picture. We know spiders have a lot of legs and make webs. We also know that spiders can be an emotional trigger for people. They can trigger fear and disgust. The poem is kind of a verbal/lyrical Rorschach test where I used words that can provoke strong emotional reactions in myself and others. Then I proceeded to break down the emotional weight of each word in the lines that follow.

JR: In “Bullseye,”

I didn’t question how

the only Black things

for miles were me,

the sky and the patches

on the dartboard.

segues to bar ‘teachers’ who coach you to your first bullseye. “There is a power / in nicking the heart / of things” is the lesson learned. Earlier, racism occurs in “The Color Game: Bounce,” when “the other kids / said I talked ‘white,’” the final stanza dominated by a racial slur. These are precursors to “Black Girl’s Rondo,” which discusses injustices spoken by writing cohorts and professors alike, its reception airs contrasting with brutality—

Or where not even cheese cubes

and wine are enough to forget

another Black body

was downed by police

This trio reinforced takeaways I gleaned from Rachelle Cruz’s article “We Need New Metaphors: Reimagining Power in the Creative Writing Workshop,” in the September/October 2020 issue of Poets &Writers. Cruz’s fifteen-item list recommends reading James Baldwin’s “A Talk to Teachers” and Dena Simmons’ “How to Be an Anti-Racist Educator,” among other salient points, such as questioning whether or not the workshop is a hostile environment “toward marginalized writers.”

Have you had the opportunity to read these poems at Zoom gatherings since last summer? If so, what effect did they have, heard aloud? Is there a memoir, poetry collection, or pedagogy essay written on behalf of writers of color you wish MFA programs would cover?

JF: Unfortunately, I never read the poems outside of workshops because I didn’t think they were ready yet. In fact, “Black Girl’s Rondo” was edited for the final time in a workshop with Shira Erlichman who helped me take the poem in different directions (omitting more unnecessary words, etc.). Hopefully, I will get to read them soon.

As for an essay, I would select Junot Díaz’s essay “MFA vs. POC.” While I know he is a controversial name now and that the essay is written about an earlier time, I still think it is relevant today. My experience wasn’t as bad as the one he wrote about, however my tenure as a grad student wasn’t fully immune from such.

JR: Visits to your father’s nursing home are referred to as a tradition that lasted nearly three years, beauty happening when birds “flit / onto one of the side doors” and you note their “plumed tapestries / of greens, rubies, and / grays” (“The Color Game, Take 2”). As “Father-Daughter Dance in Six Stages” unfolds, we encounter efforts to restore his hands, as well as your brother’s “one absence / too many.” Here, tradition shifts to vigil where the final image

…is your father—

a bruised clay,

middle fingered-

incarnate, nesting

doll of thorns.

You are not the one

to let him go.

If there was one more stage in this choreography, what would it consist of?

JF: I think the final stage would be the letting go or the living without a part of yourself. Most folks assume my dad dies at the end. Actually, we had a falling out and aren’t on speaking terms.

JR: I read “The Nikola Tesla of Compulsion” as a biographical ars poetica. The first line, “You can’t write poems.” returns six times, a word added with each appearance until we have “You can’t write poems about Mom because she loves you—.” I’m awed by the prose-variations on raspberries: “Some days, you eat raspberries to keep the taste of these words off your tongue/” becomes “Some days, not to speak of him is to drown your larynx in raspberries/” which transforms into “Some days, if you turn your headphones up enough, you can breathe past the raspberries in your mouth/.” What’s especially remarkable is that rasp- bridges my association to the voice, and how voicelessness safeguards against memorial because “Some days, there’s a grave between syllables/.” Also, the tops of raspberries resemble mouths, which I liken to all those rumors spread about Tesla. Please walk us through how you put this poem together.

JF: Wow, that poem was a doozy to write. I started writing it in 2017, a few months after Dad and I stopped speaking. For some reason, I had two Jeffrey McDaniel poems in my head: “The Benjamin Franklin of Monogamy” and “Compulsively Allergic to the Truth.” In fact, the “walk on your own two feet” and title were inspired by the former poem and the raspberries refrain came from the latter; I think I was transfixed about the idea of disguising one’s true feelings behind something sweet so as to spare the other person, kind of like when you don’t tell someone how severe a situation is so things can remain calm.

Well, I wrote this first draft and brought it to my workshop groupmates: Natalya, Jody, and Denise. They dug it and gave me some much needed feedback, particularly about the length of lines and making the lines connect. Then, I returned to the draft every now and then. The most recent version (which made it into the book), was completed earlier this year. I was working on the poem in the hopes of submitting it to a journal and I read it to my mom. She was the one who encouraged me to write a line or two that tied the whole poem back to the title, hence the convulsion line.

The whole process is a lot more glamorous than it sounds here, but it was just a matter of getting more eyes on the poem and chipping away at the work as a whole.

JR: Thank you for your words and wisdom, Jordan. The shout outs in your Liner Notes show profound gratitude for a wide net of support. From Cave Canem and the 92nd Street Y to Tim Seibles and Tina Chang, you mirror all the generosities received. I was moved by your description of Thomas Lux as “a brilliant, luminous soul who put me on the path to this book.” Lux’s “line-by-line” workshop method remains instrumental to the way I edit, teach, and think about poems. What do you treasure most about his mentorship, and how do you plan to pass this along?

JF: No problem! As for “wisdom,” I hope this interview helps.

What I treasure the most about Professor Lux is that he was one of the first who made me believe I could write—that I had a place in the world of poetry if I was willing to work for it. When I met him, I was at a real low point of my life; I graduated with my BFA the previous year and applied to a few MFA programs only to get zilch. I also had a very uncertain future jobwise. After a workshop, he took me aside and spoke to me one-on-one about my work. He said I was good and asked if I had applied to any MFAs. I told him about my abysmal first round and he offered to be one of my recommenders if I decided to apply again; he would continue to be a recommender until I succeeded. I owe that man so much and I’m sad he won’t get to hold my book or see what his support birthed.

I’m still growing as a poet and making sense of what makes me tick. Once I figure it out, I want to become a Poetry teacher myself and give the next generation the same support I was able to find in Professor Lux.

Jon Riccio received his PhD from the University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Writers and his MFA from the University of Arizona. He is a past Poetry Center digital projects intern.