An Interview with Jessica Guzman

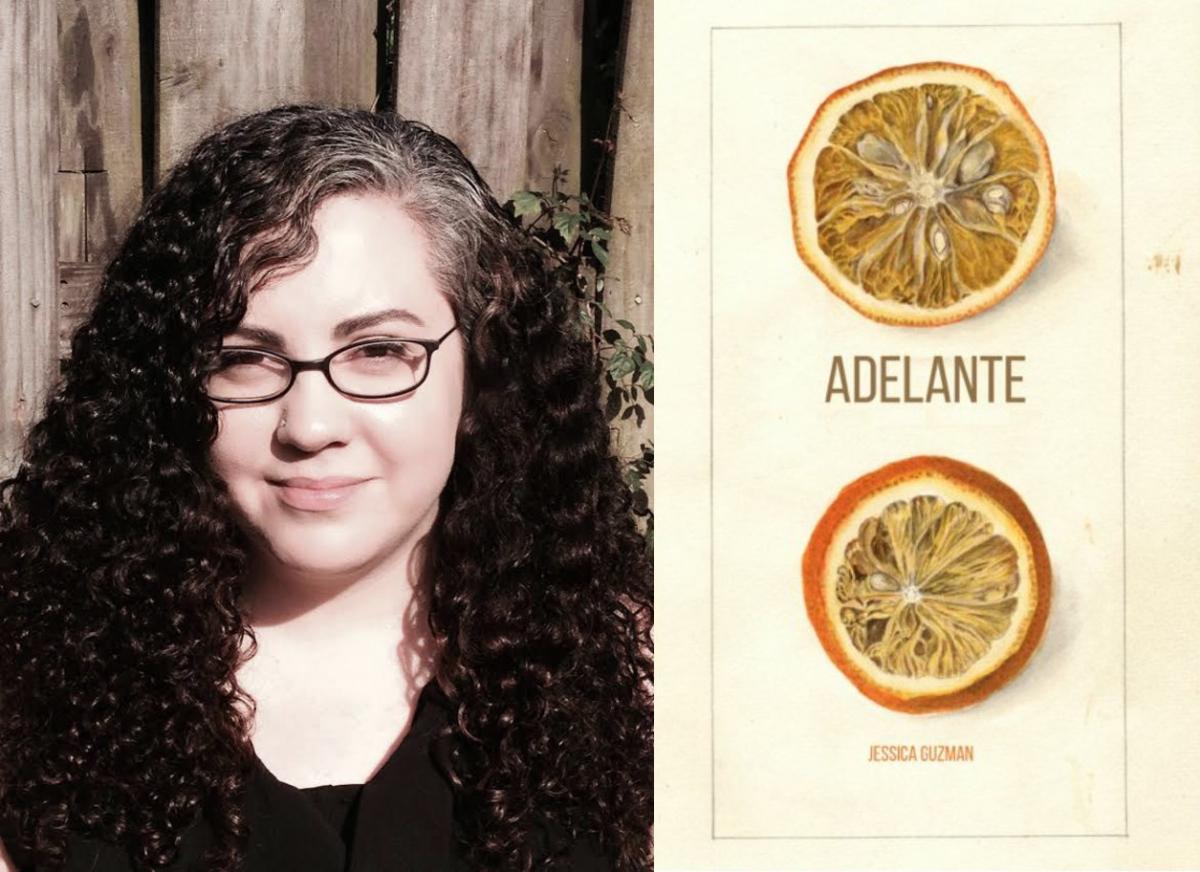

Jessica Guzman is the author of Adelante (Switchback Books, 2020), selected by Patricia Smith as the winner of the 2019 Gatewood Prize. Her poems have appeared in Shenandoah, jubilat, The Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day Series, Ecotone, and elsewhere.

Jon Riccio: Whether it was in workshops or literature classes, your poetry and appraisals of those we studied always left me awed. It’s great to see the poems I’ve known since 2016 coming together in Adelante, your images pinnacles of observational splendor. From supermarket items—“In the produce section, a ziggurat of apples falls to the floor” (“The Question is Gratefulness”)—to facial hair—

My father’s moustache

has two spots, one light in one dark,

like a black-eyed pea, or a tube t.v.

shutting off. (“Ode at the Hospital”)

you apply spectacular coats of word-paint. What do you cherish most about the image-making process? Could you distill this into a craft takeaway?

Jessica Guzman: Thank you, Jon! I do love making images, which, for me, often means rendering what I think of as the landscape of the poem. Unlike more general terms, landscape by definition suggests boundaries—a photograph’s margins, the perimeter of a viewer’s peripherals, the view from a single point, and so on. Like received form or the blank page, landscape confines; however, also like received form or the blank page, its confinement can lead to freedom in other ways. Sometimes the image-making process functions as a distraction, allowing other parts of my mind to make observations they may not have otherwise. (There’s a line in one of the poems you quoted, “The Question is Gratefulness,” that came about this way: “And all things a woman can come to with tender indifference.”) Sometimes the image-making process becomes an act of understanding the boundaries in which I’m writing, giving me questions to ask myself: what is excluded from this landscape? From what angle have I been making images? As a craft takeaway, I suppose I’m advocating for recognizing and considering the boundaries we impose on ourselves in the image-making process.

JR: The opening poem “Florida Orange” pairs the state and go-to export—

Orange I lift to my lips. Orange

I glimpse roadside: hibiscus and bird

of paradise, Florida’s Natural discarded

below orange slip of sky,

By the fourth tercet’s second line, we arrive at your father’s cancer, a core subject throughout the book—

At the hospital, oncology and hematology

follow the orange line. Three weeks

after chemo I don’t recognize

my father in the orange cap, so I enter

his room twice. Once quick to anger,

he says nothing but tugs on the lidless

Tropicana’s straw, juice spackling the Pall

Mall I never lit on the drive.

Here the color is both covering and route, the liquid byproduct never far from narrative details. How did this poem take shape? What do you think of when you write the word orange now?

JG: I first drafted this poem while at the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley Poetry Workshop. Evie Shockley gave an amazing craft talk on Confessional poetry and mythologizing our experiences. When I returned to my room that evening, I wanted to write a poem that confessed. The anaphora of orange was a way in: a way to mythologize, a way to render, a way to remember. I wasn’t sure what I was really confessing—not recognizing my father in his hospital bed?—and I let the anaphora guide me past my initial inclination. In this way, orange became “covering and route,” something as encompassing and governing as grief. I still think about orange that way sometimes.

JR: We turn the book horizontally to read “Nightingale Poem”—

In which the watch occupies a vine in Disney’s Enchanted Tiki Room, hurl animatronic

warbles from the right of the conga line and abandon genuine feathers

just as a daughter gathers her mother’s sleeve outside, squints against summer

and the fudge bar about to drip. Anyway, there is ice cream everywhere

You describe the nightingale’s song as “the opposite of endangered,” conclude with a couplet about a boy’s reckless driving—he “careens toward the whitecap, the wake worth plummeting.” How is your writing informed by enchantment and risk?

JG: I was born and raised in Florida, and so much of what I write about enchantment and risk comes from the sensibility of a person raised among tourists, retirees, and the Florida residents who create “enchantment” for said tourists and retirees. Residents like my father, who made a living setting tiles and cleaning pools for snowbirds’ second homes. I’m interested in the question: how does enchantment happen? And Disney World helps. For Floridians, Disney World looms large, a place to which all other places must compare. (Jennine Capó Crucet has a great essay about this effect in My Time Among the Whites.) Of course, the Disney experience is carefully controlled—that’s the point. But even Disney can’t control everything. In poems like “Nightingale Poem,” I’m interested in what part of the experience can be controlled and what part cannot.

JR: The Lord’s Prayer happens in “The Visible World” “when the plane / drops twice,” while in the earlier mentioned “Ode at the Hospital” “My father’s moustache talks / like Ricky Ricardo, tells fortunes, chants / ‘Our Fathers’ in its sleep.” The first poem of section three, “Coco,” features it in Spanish. I’m often perplexed writing about religion because cliché is an easy trap, yet interrogations of Catholicism account for a fair number of my poems. The contrast in “Coco” between your mother “boiling water and puffing / on a cigar” followed by “Danos hoy / nuestro pan de cada día.” is why the prayer reference succeeds, task and tobacco juxtaposed with the holy. Do other elements of faith find their way into your poetry?

JG: Sometimes, especially when I write about my family. We practiced a kind of espiritismo in our household, which shaped my childhood. Coincidentally, the Lord’s Prayer with concurrent cigar-smoking was a common occurrence.

JR: You incorporate the pecha kucha form—derived from the similarly named Japanese business practice, ぺちゃくちゃ, wherein twenty slides are given twenty seconds of description apiece—in “The Shell Factory” (after Ana Mendieta’s Silueta series). Its seventh section reconnects us with the Sunshine State—

[Silueta de Nieve]

A bird’s new plumage never breaks

winter for the Florida-raised, the instinct

to migrate, like the cockleshell

dulling the fluorescent palm.

A search of Mendieta’s series yields silhouettes ranging from what I would describe as Shroud of Turin-esque to transmogrified twigs. You’ve hybridized forms, resulting in an ekphrastic pecha kucha (wow!). What was your experience working under double constraints to produce a poem “pitched / against the glass like a grasping hand”?

JG: First, I must give credit to Terrance Hayes. I learned about the form by studying his pecha kuchas in Lighthead, and my choice to utilize the works of a specific artist was a direct imitation. Most ekphrasis I’d read until picking up Hayes’ book focused on a single art object, and I was attracted to how the pecha kucha allows a poem to converse and confer with a series. In “The Shell Factory,” I began with the memory of visiting the Fort Myers, Florida attraction with my mother. Ana Mendieta’s Silueta series explores the connections between her body and the natural world, a relationship fraught by her exile from Cuba. As I wrote, I thought about my mother’s own exile from Cuba, as well as the strangeness of being around the very unnatural rendering of nature that the Shell Factory curates for tourists. My mother and I were both struggling to connect to our surroundings. Mendieta’s Silueta series added an instructive layer to this moment.

JR: In addition to “The Shell Factory,” Adelante has a sestina (“One Rain,” its end-words break, god, shell, you, mark, here) and three ghazals, among them “Girls Lingering,” where Disney World, #metoo, and The Wizard of Oz meet—

The happiest place on earth has princesses and fathers and who

could find the hand that pinches your ass in such crowded lines.

We pitch blotting papers between the partitions of bathroom

stalls, let them fall onto the tiles’ crooked lines.

When Dorothy woke, she knew: you and you and you. We too

sleep with locked windows. Our reflections deliver our lines.

Gatewood Prize judge Patricia Smith calls your work “enviably controlled” and I concur, for there is also the “Spring Tetraptych” (the tetraptych form being of roundabout ekphrastic parentage). I once asked Patricia Smith about received form in Blood Dazzler and Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah and she said, “Form is a device in my toolbox, accessible to me when it’s needed.”[1] What would you say to poets about the inclusion of received forms, some which recur multiple times, as they assemble their first book?

JG: I am so incredibly grateful to Patricia Smith for her kind words about my work. As I mentioned in response to an earlier question, I like to think about the boundaries in which I write, and how those boundaries influence my understanding of and approach to my subject. Sometimes that means the received form becomes an exercise rather than a crucial element of the poem. I’m definitely not the first to say so, but I would second the advice to make sure the received form is crucial. If the received form is crucial to each poem in which it appears, then I think having multiple poems in a collection that occur in received forms will feel right.

JR: Snakes feature prominently in “A Body Must Be More than Bones so Why Keep the Urn.” There is the disapproving Medusa, the “Snake that squeezed my hand,” and “the snakeskin in my bed.” Their absence is understandable when “I cry my father’s died, my mother corrects / your dad’s expired, her Latinate verbs,” the only way pristineness comes to mourning. The next poem, “Finca Vigía” culminates in a funeral “where a girl buries / a cigar box, a spider / threading the lock.” Arachnids and serpents provoke some of our strongest reactions, so it’s natural they would be in poems where raw emotion and the ceremony associated with that emotion occurs. Which had a stronger pull while curating your poems’ order, memory or grief?

JG: Grief. I spent a lot of time re-organizing sections and mapping emotional narratives between poems based solely on their relationships to loss and image. I didn’t have a set trajectory in mind for the book’s order, but I knew I didn’t want the poems to move chronologically through my father’s illness and death. Chronology would’ve oversimplified. Instead, I tried to create an order that would show the complexity of loss through recurring images. The snake imagery is strongest in the poem you point out here, but snakes show up in other poems as well, both directly (such as the family crest in “Disney Ghazal”) and indirectly (such as “the red and yellow / hissing” of “Return to the Queue”). In ordering the collection, I tried to focus on how the evolution of such images could influence our understanding of loss.

JR: Rereading “Register of Futures: Florida,” I perceive a dual spectre of the necropastoral and the History Channel series Life After People (2008-10). In section two, the Atlantic laughs last—

Coral usurps

the chained pens

of bank teller stalls where barnacles

crumb the vaults,

its overtake spreading to “the decomposed / grocery cart screening a Tonka truck, / a small moray peeking from the cab.”

The gendered cloud of section four “wrings her halo” following a quake that results in “the old expanse / [splintering] to cephalophore quarters, / her human cohort unknowable in the brume.” I read the cephalophore or beheaded saint as us, whatever weapon that does the beheading forged from earth abuse. How might other moments in Adelante be interpreted as our ecological undoing?

JG: Thank you for your thoughtful reading of this poem. I hadn’t thought of Adelante as suggesting our ecological undoing, though it feels like a clear thread now that you’ve pointed it out. In poems like “Register of Futures: Florida,” my focus is usually on nature’s suffering and resilience. Coral and barnacles supplant a powerful institution, a moray makes a home of marine debris, etc., showing how nature perseveres through repurposing. I suppose the people in the poem—few that there are—fail to do so. I’m thinking of the tourists in the opening stanza, who still visit Florida to ooh and ahh, even though they must do so from planes. Other poems throughout Adelante definitely show nature repurposing, and human action often in juxtaposition.

JR: One of your areas on the comprehensive PhD exam was twentieth century Caribbean verse. Who are the lesser-known writers you studied that poets should make every attempt to familiarize themselves with, so they may be stronger stewards of Caribbean verse in this century?

JG: I love this question. I would say the following poets may or may not be lesser-known, but they are poets I would recommend you read, if you haven’t: Lorna Goodison. Grace Nichols. Jane King. Binta Breeze. Mahadai Das. Wayne Brown. Kamau Brathwaite’s poems and prose, such as History of the Voice. A very inexhaustive list, but a good start for twentieth century verse. Peepal Tree Press publishes Caribbean and Black British writing, including previously out-of-print works. Akashic Books, whose mission (per their website) is “reverse-gentrification of the literary world,” also has a Caribbean imprint.

JR: I’m thrilled we had the opportunity to discuss Adelante, whose cover by Alyse Knorr is one of the most detailed I’ve come across, those seeds accompanied by chambered pulp. What was the first poetry collection you owned, and did the cover match its poems’ intent?

JG: Thank you so much for your thoughtful observations and questions, Jon! I love what Alyse did with the cover, and I’m grateful to Switchback Books for their care in publishing Adelante. To answer your last question, the first poetry book I owned (and still own) was a collected Emily Dickinson with a blank, burgundy hard cover—a good burgundy, earthy and rich. Yes, a good match for her poems.

[1] https://thevoltablog.wordpress.com/2016/01/04/interview-dazzle-roll-call-patricia-smith/

Jon Riccio received his PhD from the University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Writers. He served as a digital projects intern at the Poetry Center during his Arizona MFA.