Jennifer Calkins is an evolutionary biologist, writer, and attorney living in Seattle with creatures including young adult humans. She is currently collaborating with Anne de Marcken on a multi-year, multi-media attempt to engage with climate change (some bits can be found at http://www.thehinterland.org). She does have a website, https://www.jenniferdevlincalkins.net/, and her writing can be found at locations ranging from The Fanzine to The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and venues in between.

Jon Riccio: I’m happy we’re discussing Fugitive Assemblage, Jennifer. What I love about your work is the choreography between page and prose, paragraphs such as this one seated in the theatre of the book—

Italicizations aside (I have plans for those!), it introduces us to the trunk mystery while casting the trip in a direction opposite our compass’s expectations. These items expound on what Fugitive Assemblage’s back cover refers to as “lyric noir.” How is this term central to your project?

Jennifer Calkins: Thank you so much, Jon, for taking up Fugitive Assemblage. You are such an amazing reader; I feel very privileged to have your close attention on this text.

Lyric technique and noir sensibility drove the discovery at the heart of this project. That said, while I found my way to these methods in a desperate attempt to draw out what was stubbornly hidden, The 3rd Thing, and specifically Anne de Marcken, coined the term and identified the genre home of Fugitive Assemblage. Together, the lyric provided the tools and techniques for excavation and the noir provided the engine of the narrative and the driving force behind the language.

Initially, I tried to explore the issue of California in my own experience and family history using prose. But prose could not access what I was trying to uncover. I broke the sentences and discovered that the lyric was the approach I needed to take for the project of excavation. The lyric form changed from lineation to interrupted prose paragraphs. But that lyric impulse was absolutely necessary for me to write into what I was trying to discover.

Similarly, I discovered the importance of the noir element, as a genre descriptor as opposed to “black” (which definition itself is entangled with the genre in not unproblematic ways). I did not immediately know there was something in the trunk. And then I did. When I wrote that she was “running from the thing in the trunk,” I discovered there was something in the trunk. And that this “thing” in the trunk was chasing the protagonist and from this “thing” in the trunk emanated dread and horror. That dread became an engine.

JR: Your text foregrounds the ties between terrain and family. The “rusted remains of my great grandfather’s farming tools lay beneath the soil” like relics in an interstate basement. The San Joaquin River is where “my great grandmother planned to drown her kids.” Did geography hold a strong influence over your approach to ancestry when drafting Fugitive Assemblage?

JC: Absolutely. Geography is a core narrative for my family’s sense of relationship and time. As I was growing up, the living members of my family were all in California, Central and Southern, and I heard stories of movement to California (over land and sea), and movement around California. My grandfather was particularly interested in exploring the ruins of mines, he was a rock hound and also sought evidence of past human presence, arrowheads or square nails. He, of course, is a central figure in the book. And while he spent time in China in the Marines just after WWII (fighting the Communists, which fact I realize now probably influenced his politics more profoundly than I understood) and lived in Mexico, and Ohio, Texas, and other US states as part of his baseball career (he played in both the minors and the majors), we only really talked about California when we talked about land, water, and space.

JR: The narrator realizes that “Bones are never simple. The earth never quite swallows them, the sea coughs them up or spills them out from the slit belly of a fish onto the deck of a ship.” Is this a book about lineage or the failed entombment of it?

JC: That is a good question. I think it is about both (I know . . . cop out!). The book is really one manifestation of my recognition that my lineage is embodied in me and that I do not occupy any space without that lineage occupying that space with me. It’s a specific Whiteness that I cannot dismiss as my inheritance. The book also, however, as this line indicates, struggles with the given articulation of lineage and inheritance. Some of that is the problem of the White narrative and political realization of Manifest Destiny as my ancestors realized it on the land and bodies of nonWhite peoples. But also it is the problem of narrative confusion. So, for example, my mother’s grandfather immigrated from Germany in 1911. The family narrative is that he helped paint the Golden Gate Bridge. But when I helped my son do a research project on my great grandfather I discovered that does not appear possible that he helped paint the bridge given when he immigrated and when the bridge was painted. So did he or didn’t he? Does it matter? I believed it and now I don’t.

JR: I toggled between Fugitive Assemblage and Joan Didion’s Where I Was From, both bridging California’s recent past to the 1800s. Didion writes, “there hung a quilt from another crossing, a quilt made by my great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Anthony Reese on a wagon journey during which she buried one child, gave birth to another, twice contracted mountain fever, and took turns driving a yoke of oxen, a span of mules, and twenty-two head of loose stock.”[i]

There’s a companionability the book shares with Didion’s essays in their tallies, yet noir aspects shuttle Fugitive Assemblage to a different California air, as seen in this excerpt, “When her father died of typhoid on the trail there wasn’t anything to do but bury him in the sandy ground and keep going. I brushed the taste out of my mouth and decided this morning I would eat.” Fugitive Assemblage’s “I” operates as a voiceover shifting from highways to hospitals to hotels. How high does setting rank on first-person’s illumination scale? Which authors best shaped your concept of the “I’s” capabilities?

JC: I’d generally rank setting relatively high (certainly higher than attempts at physical self-description e.g. “my grey eyes gazed out at me from the mirror”—to paraphrase a sadly common trope). I’ll be honest, though, I’ve been chewing on this question because I know there are instances where setting is not doing any of the work creating the “I” and yet, for the life of me, I cannot bring them to mind.

The value of setting for a first-person narrative is that, not only does it provide a sense of the space the narrator occupies, it provides insight into her way of being in the world. This is because the actual details of the setting are filtered through the narrator’s consciousness as revealed to the reader. What matters to her? What does she notice and point out? What is she not observing, not noticing or purposefully avoiding?

In terms of authors—here’s a slice but only a tiny subsection, randomly chosen based on the way my brain is retrieving memories of artistic experience: Emily Dickinson—the uniquely poetic “I” occupying language, spirituality, space; Herman Melville’s Ismael—an “I” that fades in and out nearly consumed by the other beings of the text but ultimately the survivor; and now they are tumbling out: Claudia Rankine, Hannah Weiner, Alice Notley’s The Descent of Alette, Kathy Acker, Anne Carson, David Markson, Sun Yung Shin, Wilkie Collins with his narrative of the tombstone, Franz Kafka’s remarkable “I’s,” Ingeborg Bachmann’s tormented “I’s”, Bolaño, Marguerite Duras, Clarice Lispector, Hannah Lillith Assadi’s “I” haunted by the Sonora, the “I’s” of witch trial confessions and trial testimony I’ve read as a judicial clerk, W.G. Sebald’s wandering “I’s.” The first-person voices of your remarkable poems, Jon. I’m realizing as I type this and these authors start tumbling into my mind that this is an endless list because I apparently cannot identify a coherent set of authors that have shaped my approach to first-person narrative. So, I suspect I’ve utterly failed to answer your question, but now I am sitting in company with a multitude of first-persons—a perfect gathering for the year anniversary the pandemic was declared.

JR: A new decorating kick? I notecard my apartment with favorite lines, Fugitive Assemblage’s “I was ready to be newly made but our reinvention is never subject to our own control” taped to the wall among Brian Teare’s “Let your body be your teacher” and Victoria Chang’s “Do we want the orchid or the swan swimming in the lake?” These quotes converge at the point of trust and metamorphosis. Which does your narrator trust more, the reader or the road?

JC: Fugitive Assemblage and I are honored to be on your wall and in the company of Brian Teare and Victoria Chang! (The orchid, the swan, the tension).

I’m not sure the narrator entirely trusts either. Which feels like a problematic statement for an author to make. But she does not reveal things easily to the reader. Only if the reader is willing to step into the spaces between her words will my narrator actually feed the reader the whole of what she knows and has experienced. But she refuses, for the most part, to tell it straight, always taking Dickinson’s route of telling it slant.

That said, she also distrusts the road. Or perhaps more accurately she trusts the road but distrusts her ability to read the road. She heads west, early on, but that decision sits uncomfortably with her. All along the route, she makes choices about direction, highway, landing point, but questions these decisions. I wrote this piece with the road as the narrative skeleton. So me, as the writer, trusted the structure of the road. But me, as the writer, also understands the road as construct of particular humans imposing concepts of directionality and the importance of different spaces on the land, the organisms including other humans. This ambiguity bleeds all over the narrative. At the same time, I love the discovery of a road trip. And I love a good road story.

You’ll notice that in my answer I discuss my narrator’s trust/distrust of the road and my own trust/distrust of the road. But not how I feel about the reader. That is purposeful.

JR: Twilight Zone reruns follow us from one lodging to the next. Of the episode “The Monsters are Due on Maple Street” you write, “Such an obvious ploy but it was that sort of anxiety I was feeling. Remember that, sometimes, the lights in the sky are aliens, and sometimes they are missiles. The earth hadn’t unraveled yet, but California was due to drop into the sea.” I watch Twilight Zone episodes “Eye of the Beholder” and “Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?” once a year, so we are Serling-simpatico! I’m also partial to Tales from the Darkside, which found its anthologized footing around the time Fugitive Assemblage takes place.

Ultimately, we discern the trunk’s contents, but I’ll keep them a secret out of noir courtesy. What did you learn about balancing clarity with the nebulous-eerie?

JC: God I love Twilight Zone. I’ve watched fewer Tales from the Darkside but it traffics in the same necessary vein.

Here’s a secret about how I wrote this book—I did not know what the thing in the trunk was until about 1/3 through my first draft. As noted in my Acknowledgements, it was actually Stacey Levine who read an early draft and told me what I already implicitly knew because I’d written it in: that the “thing in the trunk” was xxxx.

So, initially, I enacted the balancing act through my understanding of how comfortable I was writing a book in that nebulous-eerie realm. At the point the uncertainty was no longer sustainable, I identified for myself what the “thing” was. Once I knew, the revision process only involved being sure I remained consistent in the details of the interaction with the trunk-object throughout the book.

JR: One of your starkest statements is “Sometimes girls drank all the laudanum. At the campfire, she felt awfully sleepy That sort of thing you might not expect. Different from Adam’s daughter died of her wounds, or, they were digging a grave for a woman run over when the oxen stampeded These sorts of things make sense.”

The ending is chasmed in personal and geological starkness—

As I moved I was something else from what I’d been and what I am now.

In that moment in time I was entirely empty, completely and utterly open.

the slashed up place that is California, desert, plateau, dead volcanoes,

spent ash, the ocean the diverted rivers the sinks.

I was inside.

Throughout, your prose dovetails with “people whose voices appear alongside mine,” borrowed text forgoing end punctuation when it’s paired with your words. Fifty writers, including Brenda Hillman, Jean Valentine, and Henry Miller, constitute these voices. Seven are designated “a woman who crossed.” The author listing reminds me of columnated orchestra personnel, Fugitive Assemblage a land symphony.

Textural cohesion contrasts the sundering associated with the trunk’s raison d’etre. I liken these splices to a cousin of poetry’s cento form, “composed entirely of lines from poems by other poets.”[ii] How did you know when you’d found the right interlocking material? Trial and error? Divine jigsaw?

JC: Divine jigsaw!

These lines came from three sources—1) historical, poetic, and scientific texts directly related to California 2) Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy 3) A random selection of other texts that I had read, or was reading, around the time of writing the book.

Regardless of what, or whether, I am writing, I collect lines as I read. I’m a fast reader and tend to skip over text. To slow the process, particularly when I read poetry, I recopy lines by hand into notebooks. This brings me directly in contact with the poem/piece but it also means I have these lines in my body and in these notebooks.

I’ve discovered an alchemy of creation—when I write and then randomly, or near-randomly, bring in another author’s line, my line and their line, bumped up against each other, create a reaction that results in an emergent quality to the text. Perhaps it is divine jigsaw—there is something to the magic of alchemy in my experience of the process. But it feels out of my hands—so perhaps not prowess as it’s the interaction of the words, not my control, that brings out whatever latent qualities are there.

JR: Your Olympia-based publisher, The 3rd Thing, prefaces the book with an acknowledgement “at the southern tip of the Salish Sea on the unceded land of the Medicine Creek Treaty Tribes: the Nisqually, Puyallup, Steilacoom, Squaxin, S’Homamish, Stehchass, T’Peeksin, Squi-atl and the Sa-heh-wamish.” The poem “Ghost Trail” by Indigenous writer Melissa Bennett (Umatilla/Nez Perce/Sac & Fox/Anishinaabe) accompanies the preface, its lines “secrets / they thought were left” appearing before the reproduced cover image by Juan Alonso-Rodríguez. In what ways does Fugitive Assemblage address Indigenous displacement, and, how is your work in dialogue with Bennett’s poem?

JC: This seems like a good opportunity to acknowledge that I am living on the unceded ancestral Coast Salish and Duwamish lands. Fugitive Assemblage was written in these lands. In 1983, the year Fugitive Assemblage takes place, I lived in the ancestral lands of the Kumeyaay Nation.

I am grateful to Melissa Bennett and The 3rd Thing for including “Ghost Trail” in the book. The poem itself, in its call to singular multiple of the haunting ancestors, shares a kinship to Fugitive Assemblage’s ghosts. But, of course, the nature of my protagonist’s ancestral haunting, as one driven by colonizing great great grandparents and their offspring, is quite different from the haunting in Melissa’s poem. Melissa’s poem provides an essential throughline that would be absent from the book otherwise.

More generally, I really struggled with how to address the multiplicity of California Indigeneity, the ghosts, and active erasure both of the history and the living people whose land was stolen. At one point, Anne de Marcken and I tried to figure out how to represent the ancestral lands the narrator travels through on each page but in the end, it didn’t really reflect what we wanted it to. When I gave readings in person (before the pandemic) I played a slideshow behind me reflecting the peoples whose land the narrator traveled through. The book includes one version of a map of Tribal Nations across California. And the narrator recognizes the excision of Indigenous narratives from most of her family stories—because, as she notes Only that once she hid in a cupboard. Otherwise, there are no Indians in my family’s stories. In excision we tried to legitimize occupation.

Last year, I wrote a study guide for Fugitive Assemblage, providing approaches teachers can take to helping students engage the text. This was the writing exercise that came to me for addressing Indigeneity: If you identify as Native American, Indigenous, and/or First Nations, write over the text in black and blue sharpie, or create a map that is separate from the text, or write your own narrative that lives away from the text and put that narrative on top of the book. Or cut the heart out of the book and insert your narrative inside that space.

JR: A newer press, The 3rd Thing debuted with four collections in 2020, its artist roster grouped into a yearly cohort (2021 includes Paul Hlava Ceballos, Diane Exavier, and Summer J. Hart). Tell us about your cohort and how their interdisciplinary practices, as The 3rd Thing says, “create culture by providing necessary alternatives to what already exists in abundance.”

JC: There is a way all of our books are in conversation so, if we’d been published together in another time, there still would have been a way we would have felt connected. But because we were all published at the inception of the pandemic, and each of our books touches on aspects of trauma, struggle, and relationship within and across communities in and over time, our cohort developed uniquely deep connections in the context of the pandemic.

Each book in the cohort is in conversation with the others, in a way. Not directly, not in a call and response textual shaping sort of way but in the way that each treads into similar spaces, describes the shapes of those spaces in slightly different ways and, in concert with each other, stays in company with one another in these spaces. We read each of these books right after they were published and met on Zoom to talk about them.

Both Marilyn Freeman’s The Illuminated Space and Megan Sandburg-Zakian’s There Must be Happy Endings are nonfiction prose. Marilyn’s book provides a rigorous and deep exploration of the video essay and of actively working in spaces of trauma. It’s a book that is full of light, that is not weighed down but is remarkably precise and knowledgeable. While my book drops the reader in the heart of trauma, Marilyn’s book explains why one might need lyric noir and juxtaposed appropriated text to communicate trauma. It was through Marilyn’s book that I learned that what I experience as a person with post-traumatic stress syndrome is the two timelines always running: trauma time and real time.

Megan’s book is a series of essays interrogating theatrical spaces, based on her own experiences in these spaces, most recently as a director and teacher. At the heart is a conversation about the traumatic and violent, and a discussion of what a truly happy ending is—something that is necessarily a part of the activist and revolutionary spirit. And not, perhaps, what we might think it is upon first glance. Incidentally, it was in reading Megan’s book that I realized that Fugitive Assemblage itself has a happy ending.

Carlos Sirah’s The High Alive: An Epic Hoodoo Diptych is poetry—epistolary, dramatic, and ritualistic. It shares a genre relationship with my book. But my book is remarkably solitary. My narrator interacts sparingly with living people during her journey. A motel manager here, another person picking up Taco Bell there. Whereas Carlos’s book is full of living people in relation with one another, in love, in violence, in historical trauma, in the trauma after war, in a space that is where people live in community after the war has destroyed the space.

One half of the Diptych, The Light Body, is a love story, haunted by violence and trauma but also filled up with real love and tenderness. The other half, The Utterances, is a community occupying a landscape destroyed by war, where bodies lay in the roads and Theory of Bessie engages in a ritual, a ceremony, a celebration. To quote from Carlos’s book:

Theory of Bessie—cults of fragment, heralds of possibility,

interpreters of remnant, gather us in festival. Together. Each theory

within Theory of Bessie converges, pressing down foothills, into

valley, where you listen and wait.

To witness.

Theory of Bessie instantiate the recollected city . . .

Theory of Bessie unsettles story.

Those who will tell the story do. Theory of Bessie performs.

A city emerges

The Utterances, pp 16-17

Our books are further tied together by the covers showcasing Juan Alonso-Rodríguez’s brilliant images and Melissa Bennett’s poems.

JR: Thank you for your responses, Jennifer. I’ll soon pay Fugitive Assemblage another visit with today’s insights. In the meantime, I always wanted to ask an evolutionary biologist if there are any jaw-droppingly little-known facts about humankind’s ascent and whether writing plays a role in them. At the very least, I’ll settle for why the right hand became dominant.

Do your current literary projects interface with the sciences?

JC: They do. I’m currently collaborating with Anne de Marcken on a multiyear, multimedia project engaging climate change. The science comes in for me in a few ways. One is in my study of the science of climate change. I understand the climatology at the most basic level; more accessible to me is the impact of climate change on living systems, particularly given evolutionary processes and ecological space. So I am following the science, especially when people publish analysis of impacts on biological systems.

Right now, I am working on a series of poems as part of the project. The science emerges in the poems and it emerges alongside the poems in the forms of notes. I am playing with the collision of text, science, relationship, and grief.

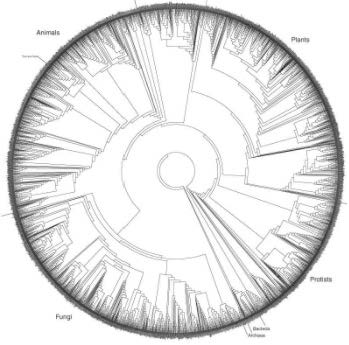

I do not know that we have a good explanation of handedness, although to be honest I have to admit to being way less interested in the evolution of human traits than the evolution of traits in other species, particularly birds—and of course, researchers have recorded handedness in some parrot species, among other nonhuman animal groups. I do have to mention also that I do not believe in human’s ascent because I definitely do not think we exist at the peak of some sort of evolutionary trajectory but rather at the end of one line of many, like this figure, showing, not ascendency, but relationship:

Jon Riccio’s chapbook Prodigal Cocktail Umbrella was published by Trainwreck Press in March. He serves as the poetry editor at Fairy Tale Review and is a former University of Arizona Poetry Center digital projects intern.