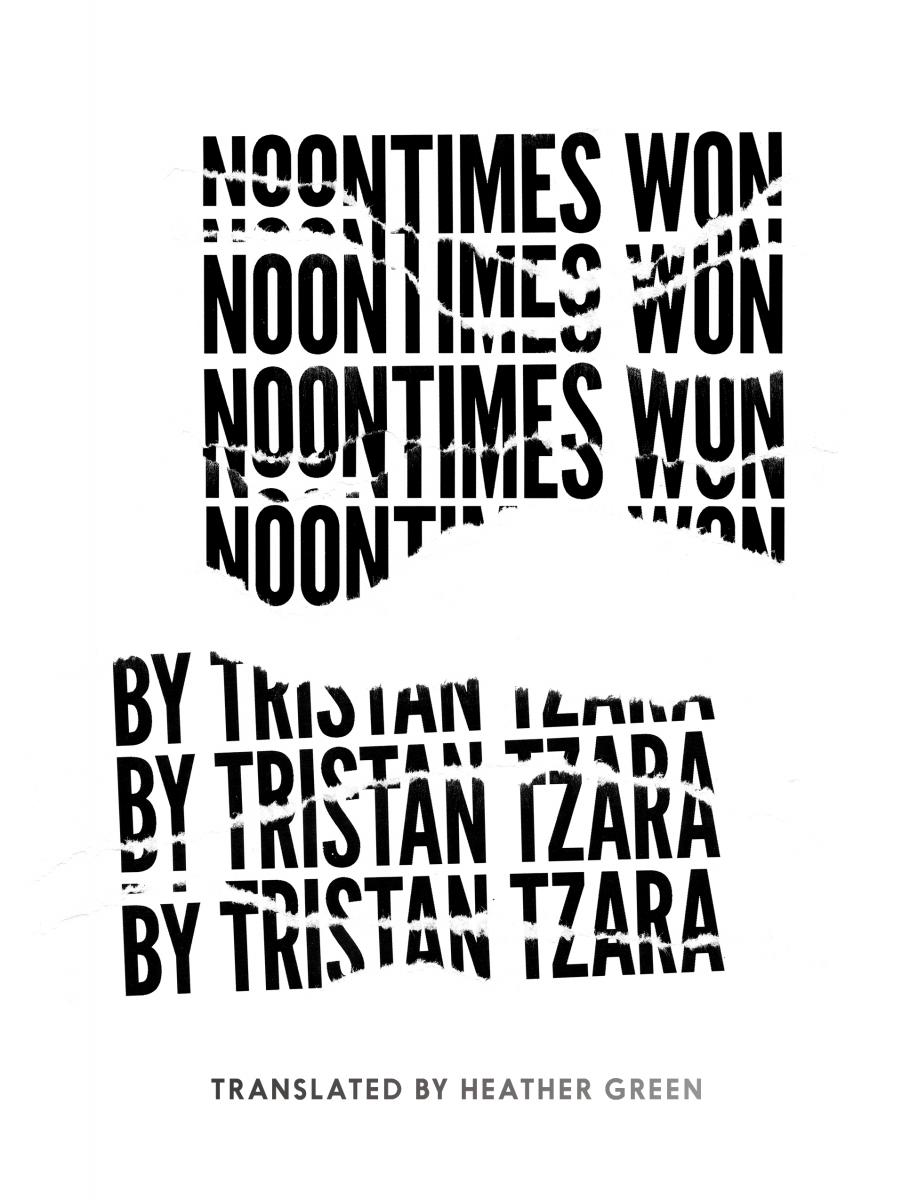

Interview with Heather Green, Noontimes Won, translation of Tristan Tzara

Heather Green is the translator of Tristan Tzara's Noontimes Won (Octopus Books) and Guide to the Heart Rail (Goodmorning Menagerie). Her poems have appeared in Denver Quarterly, Everyday Genius, the New Yorker, and elsewhere, and are forthcoming in the Bennington Review.

*

Holly Mason: How & when did you become interested in Tzara’s work?

Heather Green: I grew up in Orange County, California, where there wasn’t a wealth of “avant garde” poetry in circulation. But there was a Rizzoli bookstore at a nearby mall that had a very interesting selection of books. There, as a teenager, I found Paul Auster’s Random House Anthology of Twentieth-Century French Poetry, and it became a touchstone for me. Of all the poets in the collection—and I loved Césaire, Aragon, Desnos, and Jabès—I kept returning to Tzara, translating him in the margins, memorizing the poems, and also discovering the difference among translation approaches. For example, there’s a really playful, boisterous adaptation of one poem by Jerome Rothenberg next to these delicate Lee Harwood renderings. Later, I read and loved MaryAnn Caws’ and Pierre Joris’ translations of Tzara.

HM: Can you give us an inside scoop into your translation process? What are some of the challenges one faces in the translation process? What are some of the most thrilling moments?

HG: When I’m working on Tzara’s poetry, almost all of the moments are thrilling for me. Poem by poem, I’ll try to get one working draft of a sequence or collection of poems, looking up words and phrases, and creating a version with lots of bracketed alternate words, phrases, and lines. Though I know a lot of translators frown on the “line by line” approach, I often do work in units that correspond with Tzara’s lines, though I rearrange as “needed,” because he tends to build poems in great stacks of unpunctuated, nested phrases and clauses, using the line to parse the syntax. A fairly tame example from Noontimes Won, comes from the poem “Civil War Song”:

c’est moi qui ai écrit ce poème

dans la solitude de ma chambre

tandis qu’à ceux pour qui je pleure

la mort est douce ils y demeurent

i’m the one who has written this poem

in the solitude of my room

while in those for whom I weep

death is sweet there they abide

In the above stanza, I loved the intimacy and simplicity of the address--it’s me, writing the poem, alone in my room--that opens the stanza followed by the wrenching complexity of both syntax and meaning in the second half. The people mourned by the poet are both “abiding” or even “enduring forever” in death and death is “soft” or “sweet” in them, in a kind of recursive logic that argues, paradoxically, for the totality of their absence and for their staying power.

Once I’ve gotten a draft of a whole sequence, I’ll go through and think about the vocabulary Tzara is using. A collection of poems, for him, is often a system with a very particular, truncated vocabulary. Where it works, I like to try to make a similar sense of word and sound patterning in the English. I’m not dogmatic about using the same word in English each time a repeated French word appears, but I’ll at least try to think about it and create a similar system of sound and sense in the English. During this time, I’m reading all the scholarship and related material I can about the work, seeing if I can get a deeper understanding of what Tzara was doing. If I was working with a living author, this is where I’d send them a huge list of questions! Then, I’ll just keep working on it, revising, leaving it alone, and trying to make the poems “take wing,” as Barbara Guest would say, and ask a few people for feedback.

HM: What is your relationship with French?

HG: No one in my family speaks French. I started studying it in junior high school and continued into college, including a somewhat catastrophic “study abroad” in Corsica. However, I took many years off from speaking or reading French in between my college years and the time I started seriously working on translations of Tzara’s work. For the past ten years, I’ve been working to improve my French whenever I can. I’ve worked with a tutor, stayed in Francophone places, listened to French podcasts, and I’m about to take a phonetics course at the university where I teach. I bring a stronger background in poetry than in French to this work, but I’d still like to tilt the balance. Dominique Guérin, a native French speaker I met through a mutual friend, read over the manuscript of Noontimes Won and gave me essential feedback.

HM: I’ve seen translated books of poetry that both include and do not include the original language next to the translated. Was this a clear and simple decision for you to include the original and translation side-by-side or was there a deliberation process behind this decision?

HG: On the one hand, I really wanted to present the book as a work of vital poetry, in conversation with contemporary poetry, and not as a scholarly artifact. I recently read Andrew Zawacki’s translation (from French) of Sebastian Smirou’s See About, which is printed only in English, and it seemed to me that using only English in that edition made, successfully, a kind of implicit argument about reading the translation on its own terms.

Still, I like reading bilingual editions, and I like the idea that the poem, when you’re reading in translation, lives somewhere between the original and the many translations available, or, as Stephen Tapscott says of the “pure” Paul Celan poem (his quotes) in the recent Into English anthology, that the poem “exists at the intersection of its individual versions and interpretations.”

Zachary Schomburg, Octopus Books’ publisher, and I both somehow envisioned this as a bilingual edition from the beginning, and, thanks to the Hemingway grant, it was possible.

HM: Congratulations on receiving the Hemingway Prize from the French Ministry of Culture for this book! Can you speak about that award a bit?

HG: The French government offers different kinds of support for works translated from French. Once Octopus Books had accepted the manuscript for Noontimes Won, we realized that the permissions costs were fairly prohibitive. Octopus Books’ then managing editor, Alisa Heinzman, and I applied for the French Voices grant, which provides money for both the translator and publisher of a work from French into English, and, though we didn’t get that one, we were delighted they instead awarded the Hemingway Prize, which provides the publisher with funds for rights and permissions from the French publisher.

HM: If you could ask Tzara a question or two, what would you ask him? Or what would you like to say to him?

HG: I feel like I’ve been in conversation with Tzara for most of my life, and he was so prolific—he published almost 50 books in his lifetime, of poetry, plays, art history and criticism, manifestoes and writing on poetics--I’ll never get to the end of it. Of course I wish I could ask him all sorts of things about his life and ideas and work. I think I’ve read he claimed not to speak English, but in fact as a teenager he translated both Whitman and Shakespeare (parts of Hamlet) into Romanian. I don’t know whether he was working from extant German or French translations.

Something I often ask myself is, given his radical aesthetic sensibility and his intense political engagement, what would he be doing if he were alive today? What kind of writing, political engagement? Would he be shunning technology or making art with it? Would he favor radical translations of his work over more “traditional” language-to-language translations like I’ve done? Would he want both?

Recently, I corresponded with a poet who encouraged me to do a larger volume of Tzara’s work, and, as I grappled with the idea in our email correspondence, he suggested I ask Tzara what he’d like. Though I do feel we’ve been in this “ghostly” dialogue for so long, to borrow a metaphor both Christian Hawkey and Michael Emmerich use in relation to translation, it hadn’t really occurred to me to “ask Tzara” directly, but I did.

HM: What about Tzara’s poetry and/or life connects with your own ethics and/or aesthetics?

HG: Though my day to day life is wildly different than I imagine Tzara’s was, I’m inspired by the energy of Tzara’s early work, his ethos of revolt, and his more belligerent writings and Dada trickster image.

However, almost all of my work in translating and advocating for Tzara’s work has been motivated by my sense that he is wrongfully relegated to that single image. I’ve heard or read Tzara described, somewhere, as a poet of doubt. My sense of Tzara, as a thinker and a human being, especially from the time he broke with Surrealism and got more involved with political activism during the Spanish Civil War and beyond, is that he was a seriously ethical person, constantly using his powers of thought and language to reconsider the changing world and his responsibility and role in it. Always foremost a poet, he was also a father, friend, diplomat, humanitarian, journalist, speaker, organizer, critic, and scholar. He was a Romanian secular Jew who lived most of his life in exile, but also chose to become a French citizen and forged a place in the French literary canon. I’d like to see him read in light of the heart and dynamism and integrity of his multifarious work, in addition to the glorious mayhem of the peak Dada years.

In terms of my own connection, referring back to Tzara’s “poetics of doubt,” I probably identify most with that aspect of his poetry, the way it energizes the many paradoxes in his work. Reading Tzara is the best experience, for me, of what Kate Briggs, in This Little Art calls: the “everyday complicated miracle of reading books written by other people,” and further, “what reading offers us: occasions for an inappropriate, improbable identification.”

HM: Considering that you teach a graduate translation course, can you give any book suggestions or tips to those interested in translating poetry? Also, if you have any other book recommendations, please do tell.

HG: I heartily recommend Kate Briggs’ This Little Art, which I quoted above: an extended lyric essay on the art, craft, and history of translation, and a reflection on her own process of translating several volumes of Barthes’ lectures. I keep dipping back into it, admiring its generosity of mind and the luminous tangle of connections she proposes. I love the way David Ferry plays with intertextuality--between his translations and his poems and even other English poems--in his books Bewilderment and Of No Country I Know.

Susan Bernofsky’s blog Translationista is an invaluable source for information on all sorts of things happening in the world of translation. I was lucky enough to hear her speak in my translation class when I was a graduate student, and her passion for translation made a huge impression on me.

In our class, we’re reading Madhu Kaza’s Kitchen Table Anthology, a volume that sprung from an edition of Asterix journal, edited by Kaza. Her introduction is a powerful statement on translation from the point of view of a heritage speaker, an immigrant, what she calls a “translated body,” in which she conceives of translation as an act of “hospitality that recognizes both the dignity and the difference of the other.” The volume contains translations by writer/translators Don Mee Choi and John Keene, who have both written fascinating texts about translation, as well as Rose Alcalá’s translations of Cecilia Vicuña’s work, which I’ve also been reading admiring elsewhere.

Paul Legault, whose English to English translations are playful and interesting, introduced me to Sophie Collins’ Currenly & Emotion: Translations, an anthology in which the texts were chosen for “their potential to challenge dominant perceptions of poetry translation.” I recently heard a brilliant talk by Sawako Nakayasu, whose work is featured in this anthology, in which she discussed her interest in applying queer theory to thinking about translation, considering translation as a nonbinary practice. That thread is very much alive in this book. It also connects, for me, to critic Stephen Forcer’s fascinating critical writing on Tzara in Dada as Text, Thought and Theory, in which he reads Dada texts in conversation with, among other things, psychoanalytic and queer theory. All of these works have stimulated my thinking on translating Tzara and opened up a lot of wild (and still inchoate) possibilities in my mind for what might come next.

Holly Mason received her MFA in Poetry from George Mason University, where she taught undergraduate English courses and served as the blog editor for So to Speak: A Feminist Journal of Language and Art. Her poems have appeared in Rabbit Catastrophe Review, Outlook Springs, The Northern Virginia Review, Bourgeon, and Foothill Poetry Journal. She received a Bethesda Urban Partnership Poetry prize, selected by E. Ethelbert Miller. She has been a reader and panelist for OutWrite (A Celebration of LGBT Literature) in D.C. She currently lives and teaches in Northern Virginia.