An Interview with Devon Balwit

Devon Balwit writes and teaches in Portland, Oregon. Her most recent collection is titled A Brief Way to Identify a Body (Ursus Americanus Press). She is also the author of an ekphrastic collection, Risk Being / Complicated with artist Lorette C. Luzajic (Amazon), We Are Procession, Seismograph (Nixes Mate Books), The Bow Must Bear the Brunt (Red Flag Books), Where You Were Going Never Was and In Front of the Elements (Grey Borders Books), Where the Blessed Travel (Maverick Duck Press), and Forms Most Marvelous (dancing girl press) Her individual poems can be found in The Cincinnati Review, Fifth Wednesday (online), apt, Grist, and Rattle, among others. For more on her book and movie reviews and individual works, see her website at: https://pelapdx.wixsite.com/devonbalwitpoet.

Jon Riccio: I’ve enjoyed your poems over the years; so glad I finally have one of your collections. What a treat reading We Are Procession, Seismograph (2017). Composed entirely of prose poems, the works form a brigade where Zeno’s Paradox mingles with childhood chants (“Ollie, Ollie Ox in Free”), while a curiosities cabinet introduces us to a needle that “unsugars the blood.” And, as you state, “I Box the Forms.” I keep toggling between prose and procession, the latter capitulating to movement because the laws of physics require it. Does prose give your writing a specific momentum that lineated poetry lacks?

Devon Balwit: Prose does. The prose poem compresses, and the small prose poem (most of the poems in this collection are less than half a page and the longest is no more than a page-and-a-half) demands even more succinctness. In the pressure-cooker of the small poem, language is forced to work even harder than it does in the already distilled genre of poetry. One image follows upon the heels of another. They chase and wrestle. Or perhaps, in other words, prose needs edginess to escape being prosaic. To use prose for one’s poetry, one must whet it and hone its jaggedness.

When writing poems in stanzas, I stop and think, “Where will I break the line?” “How many lines do I want in each stanza?” “Do I want end-rhymes?” “Do I want to use a particular meter?” “If I play with the spacing within the poem, will a future journal be able to handle the variations, or will they be lost—and why do I feel the need to add spaces anyway? Is it organic to the poem or just a way of being “trendy”?” As you can see, this is a lot of mental chatter. It slows one down and makes for a different type of poem. But if I begin already knowing that each poem will be set in a 1 ½ by 3 ½ frame, I can give myself over to the urgency of the inspiration—the image (as many of these poems had ekphrastic beginnings), or the quotation, or the musing that awakened the poem.

JR: “As Usual” contrasts Proust with “the flung gust of someone’s carfuck”—oh, that sonic stairwell of short u sounds! Historic moments such as “the Berlin wall crashing, the first Gulf War” trod in the aftermath of French ticklers and a variegated porcupine, though we end on “something ordinary.” How would you characterize the poem’s arc in light of writing that’s not afraid to knock its literary boots?

DB: I had recently listened to Steve Lacy’s As Usual, in which the melody slowly emerges from cacophony. The lyrics, superimposed over the melody and sung by Irene Aebi, are not poetic or even pretty. In fact, they seem to be mocking the idea of loveliness, repeating “At the usual time / in the usual place…As usual…” like machine gears stamping out a product rather than expressing the lyricism of a jazz chanteuse. Ho hum, hum drum. But hearing that tune blasted me from the present moment back to my teens, when I spent many enjoyable hours sitting on the couch, smoking a joint with my Dutch stepdad as we listened to avant-garde jazz. Remembering a condom I had passed on the road earlier that morning, it was a skip and a hop to my role with youth as an educator. In the late 80s, at the height of the AIDS epidemic, I would regularly invite the safe sex man to come and teach my classes how to use condoms. Many students were quite conservative and scandalized, but I felt it important to make sure everyone had choices about exploring their sexuality safely. This backwards-looking also made me think how impossible it is in any moment we are living to know what is important. The moment’s anxieties fragment experience into a rubble field and only time + distance can allow us to pick through it and turn it into something other than discard. When I think back to the 80s and 90s, so many world-shattering events occurred that I didn’t give much thought to. I was too worried about MEMEMEME (and probably still am). Only in retrospect can we think, “Wow! That was history!” or “That was part of the turning of the world in X direction.” It’s ironic I included Proust because, at the time, I hadn’t read him for years, and then only fragments of Swann’s Way. Just this year, I finished all seven books of In Search of Lost Time. Its best portions/insights are well-worth the slog through the rest. Perhaps had I written the poem immediately after, I would have incorporated lesser-known references than Combray and the overused Madeleine.

JR: The medical ephemera of Steve McQueen takes center stage in “Repulsion,” where a “pretty designer tells the camera our DNA floats free, unpatented, and can be netted.” Only the bovine take a crack at disgust, “recognizing the kin in skin. Leather. I totally wear that.” In what ways do science and animal ethics influence the collection?

DB: Science plays a huge role in everything I write. While I know that no poem can escape the subjective experience of its author, I get bored writing autobiographical poetry. Scientific discoveries, the history of science, the oddities of science (the cabinet of curiosities), the natural world are “the green fuse” that drives my poems. Science, Art, Literature, and Philosophy provide the major currents of my poetic inspiration.

Recent books on science that have inspired me are Phantoms in the Brain by V.S. Ramachandran and Sandra Blakeslee, I Contain Multitudes, by Ed Jong, The Tangled Tree, by David Quammen, Phi by Giulio Tononi, Rabid by Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy and Lab Girl by Hope Jahren, among others. I read, and I ask myself: What is consciousness? What is animal intelligence? Does our impending extinction “matter”? What kind of threat is AI? What do we “get” from a close connection to nature?

Nicelle Davis wrote a killer chapbook about elephant extinction, Elephants, which devastated me as did Nickole Brown’s recent To Those Who Were Our First Gods. I have shelves full of books of botanical illustration, field guides to birds and mushrooms, collections of beetles, scientific musings on the life of ants, wasps, crickets, hawks. Current species and habitat loss and the impending 6th extinction terrifies and depresses me. Of course, this makes its way into my poems.

As to the “I totally wear that,” I’m the first to admit how easy it is to lament and how hard it is to make deep changes in one’s habits that would make such lamentation unnecessary. Were I to assemble the plastic I use each year, it’d be a significant mountain. I wear leather. I’m mostly a vegetarian, but occasionally to the dismay of my son, I’ve been known to call bacon a spice—and I admire the intelligence of pigs!

JR: “Wrack Line” opens with mention of suicide. Later, “The days repeat themselves, a semaphore of want, a dark stoop of talon, piercing.” Talon gives a note of flight, escape, yet it punctures. Should one of contemporary poetry’s goals be the possibility of respite when worldly convalescence is least optional?

DB: I don’t know if I feel comfortable with the word “should,” but poetry (contemporary and classical) certainly does provide respite. Just the other day I was feeling desperate—bleak, hopeless, insignificant, and vile—perhaps, you can imagine the feeling. Honestly, it was “do myself in or write a poem.” I wrote, and cliché or no, I felt better for it. That has been my experience time and again. The act of creation changes me from passive victim to active agent. It turns the knife of self-hatred towards carving something on the page and not in the “self.” I also experience a lot of chronic pain, which can be deflating, corrosive, and oppressive. Writing shifts the pain, lightens it, at least temporarily while I am creating, and often for hours afterwards. Now, whether my poems provide a similar lifeline or uplift for anyone other than me, their maker, I cannot say, but the possibility exists. As you may know, I am a huge fan of Sylvia Plath, contributing regularly to The Plath Poetry Project (https://plathpoetryproject.com/). I have been writing with the project for over a year now, taking as inspiration the same set of poems from the year before her suicide. They are so rich. Each time I read them, I find new entry points into my own poems. Of course, it would have been better had Plath not killed herself, but that her work continues to be so vibrant and evocative, continues her “meaning” in / for the world. Paul Merchant writes stunning translations of classical poets—Horace and Catullus—he brings their work to life in a modern idiom. A.E. Stallings, too, evokes classical poets and their forms. This is resurrection, indeed. To have such an effect long beyond our death is what all of us who write hope for.

JR: Could you tell us more about the photo by Argentinian artist Nicola Constantino that inspired “(Tenderly)”? Speaking of art-inspired, you’re a frequent contributor to Lorette C. Luzajic’s online journal The Ekphrastic Review. How did your collaboration with Lorette in self-publishing the chapbook Risk Being / Complicated come about?

DB: Rather than speak to a particular image, I’ll address my larger fascination with ekphrastic poetry in general. My mother is an artist and art educator and my stepfather a photographer who headed the Detroit Museum of Art’s photography department for many years. Thus, I grew up wandering the museum and lived in a house surrounded by art, art books, and artists. As a kid, I hated abstract art, preferring accessible realistic, fantasy works, or illustrators like Aubrey Beardsley or Lynd Ward. Now abstract and collage art are among my favorite for writing as the stories such canvasses tell are so open-ended. The texture may have the dominant voice, or the color, or the composition. I love the startle, the sudden shift from abstraction to narrative—how the image finds / demands a particular voice.

The internet makes it easy to stumble upon the works of both older and contemporary artists. I encountered Lorette C. Luzajic’s work online, and its playfulness, composite nature, and the lyrical nature of her titles spoke to me. (I think many of them are song lyrics, but because I know so little pop music, they read like snippets of poetry and had no associative baggage from their source songs…I reached out to her, asking her if she would be open to a collaboration. To my delight, she said yes.) Every one of the photographers and painters I have queried have said yes to collaborations. I have written a whole (still unpublished) chapbook with the Dutch radiographer Arie van ‘t Riet. I have written poems from the paintings of Cristina Troufa and Laura Page, and from so many others—works by artists living and dead. If I ever feel fed up with verbal inspiration, I go to sites like ars gratia artis, mutatis mutandis. It always inspires.

It’s a given that the arts would speak to and inform one another, emerging as they do from the same ur-source.

JR: The Buddha features prominently “In Contrast.” “How understanding the bodhisattva of all that collects in his cracked places, the patina of lowliness,” you write. The next poem, “Though the Waters Thereof Rage and Swell” draws inspiration from Psalm 46. Where does spirituality fall in your seismograph’s aesthetic?

DB: Sacred texts with their koans, psalms, parables, and their attention to foundational stories, rituals and life-transitions, are rich in poetic inspiration. I don’t practice any religion, but I have in the past. I identify with Judaism both culturally and historically. However, over the course of my life, I have been baptized (full immersion!) into churches more than once (and even excommunicated for apostasy!). I reject the dogma of faith and don’t believe in God but am drawn to many of the rites—prayers of confession for sins of commission and omission, passing of the peace, welcoming in the sabbath, sitting in silence, sharing the concerns of the congregation—and the way those rituals organize the year. Religious stories have been the source of many of the great pieces of music and paintings from which I take inspiration, so it has been important for me to know my Old and New Testament. I meditate daily before I do anything else—mostly a fretting in place, alas—but I have had glimpses of how it might work to distance one from the perturbations of the “monkey mind.” I draw the most spiritual comfort from being outside in natural spaces or from creativity and creative production.

JR: Instruments of illumination play meaningful roles in the first sentences of “Prophet” (“The lamp lifts two blind sockets from the trash.”) and “Fukushima” (“The empty town runs with boars, cells lifting Cesium lanterns as they scavenge.”). Silhouettes likewise initiate a pair of poems—“Caravan” (“Our shadows show what we are.”) and “Evening Chorus” (“The hills funnel shadows onto the jacarandas, Scriabin bruising the silence”). In “(Pensive)” the mediums converge: “Pensive, I hold both light and shadow, pass from I to I as on stepping stones across mirrored water.” Does this, or any other duality, echo throughout your previous collections?

DB: Without the tension of dualities, no writing would exist. There we are in the moment, then suddenly something snaps us out of it into the timelessness of the creative urge. We are no longer content just to be but have to make something of our being, make it “meaningful.”

Four of my chapbooks are inspired by single authors: Flannery O’Connor (Where You Were Going Never Was, Grey Borders Books), Herman Melville (The Bow Must Bear the Brunt, Red Flag Poetry), Sylvia Plath (A Brief Way to Identify a Body, Ursus Americanus Press), and Marcel Proust (A Phenomenon of Light, still looking for a home). Thus, there’s always the tension between my own voice / these other writers’ voices—a more acute version of the self / other tension. When I immerse myself in another writer, I adopt their cadence or aspects of their vocabulary, which is in tension with my own usual way or speaking or my typical vocabulary.

My poems often voice the tension between sane / crazy, arrogant / insecure, sick / well, mind / body, gendered / genderless, human / animal, restless / still, historical / current, and so on. (I’m sure an attentive reader could find even more.) Poems make a space for the both / and of these dualities, stretching to contain the two warring elements, and vibrating between each charged pole, sometimes closer to the one, sometimes the other.

JR: Having recently read Toni Morrison’s Sula, its characters Plum and Shadrack experiencing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder due to World War One, I interpreted “From the Trenches” in the same vein. These men know “the hungry ground swallows us up.” They “shout mother, mother in a vast fugue, voices all around.” What poets influence your writing on conflict and atrocities such as the Holocaust, alluded to in “Repulsion”?

DB: I tend to draw more inspiration for my writing from novels and histories than from other poems. Reading poets teaches me about how to say things more eloquently, but not necessarily about what to say. Still, I have been influenced by poets such as Primo Levi (and by his prose work as well), Wisława Szymborska, Zbigniew Herbert, Martin Espada, Alan King, Terrance Hayes, and David Smith-Ferri. I have been moved by novels like The Noise of Time by Julian Barnes on Shostakovich’s experience in Stalinist Russia, Kolyma Tales by Varlam Shalamov about life in the Soviet gulag, and The Regeneration Trilogy by Pat Barker on trench warfare, shellshock, and homosexuality in WWI. I’ve learned a lot from history books like The Vertigo Years and Fracture by Phillip Blom on World History between 1900 & 1939 or King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild on the atrocities of the Belgian Congo, or Last Train from Hiroshima by Charles Pelligrino. Who could not be moved by accounts of humans in extremis? These traumas present us at our most cruel, our most despairing, our most noble. Usually, those suffering through them are not able to speak of what they are experiencing—they lack enough distance or physical ease—or they have been incarcerated or murdered and cannot. Thus, we others must stand as witnesses.

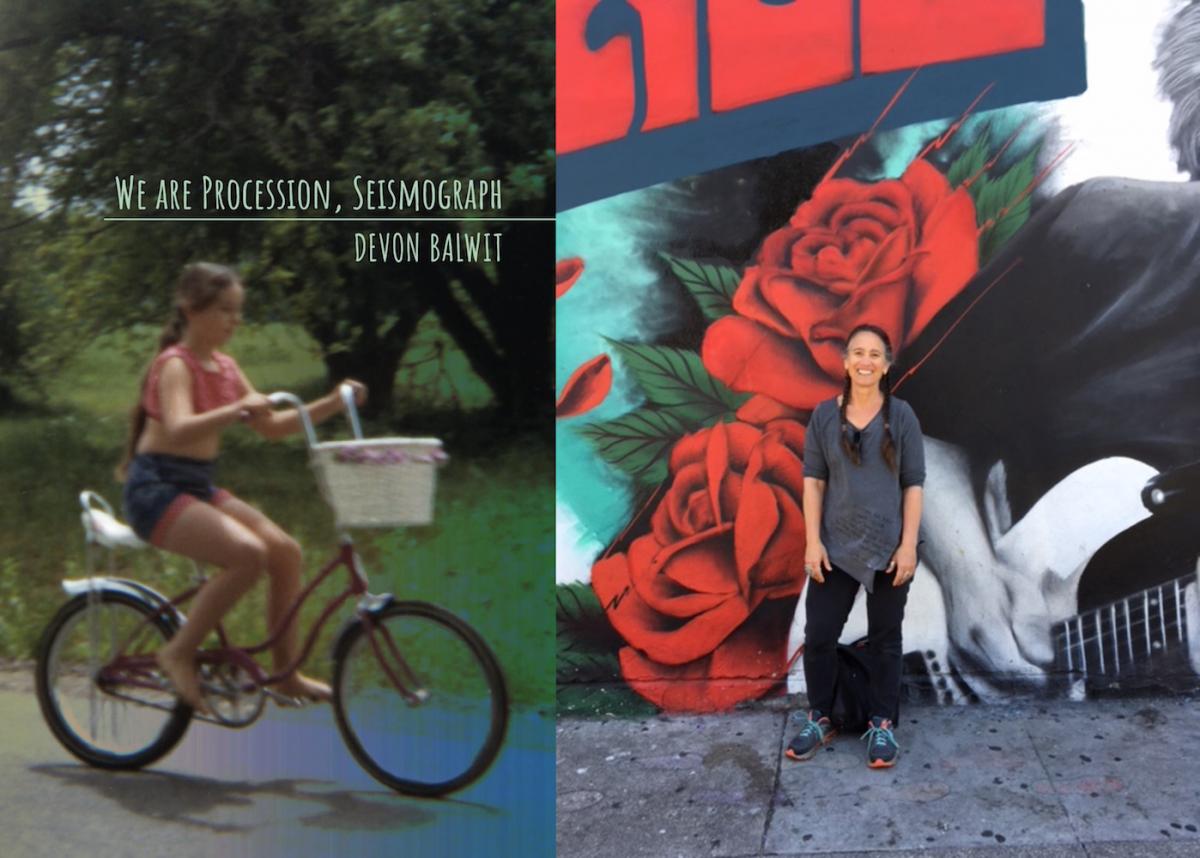

JR: How does We Are Procession, Seismograph’s narrative align with the vision of your publisher, Nixes Mate Books? Also, I’m curious, regarding the slightly blurred cover image from Lauren Leja’s photography collection. Is distortion the catbird seat to art-fueled truth?

DB: This would be an interesting question to ask Michael McInnis. I’m always interested in what drew a publisher to my work (just as I’m interested in knowing what makes some publishers reject my submissions time and time again…). I’ve read five different books from Nixes Mate Books, and they differed from one another greatly in both style and content. I didn’t notice a “common aesthetic.” In terms of the covers, I know that Michael had a retro aesthetic he was working with for a while. I probably did have a banana-handled bike like the one on the cover of my collection and even had hair that long at various points in my life (although that isn’t me on the cover). Distortion is the best we can do as beings bound by bodies and fallible individual consciousness.

JR: You’re a Portland resident, so hopefully we’ll meet at this year’s AWP (my only other trip there was spent mostly at Reed College with a brief trek to Cloud City Ice Cream). Various online bios highlight your Portland-area work as an adult ESL instructor. What facets of poetry enrich your language-ambassador life and vice versa?

DB: I’ve studied quite a few languages: Japanese, German, Italian, French, Spanish, Dutch. I can catch little bits of Hebrew and Arabic. I try to pick up bits and pieces of my students’ native tongues and imitate their intonation and body language. A Japanese student recently spoke of how learning English made her appreciate Japanese more. She said that, in her opinion, her mother tongue was richer and more nuanced than English. We discussed why at length. Her comment served to decentralize my own language, which of course I know best and can’t help but privilege. They will sometimes gift me with untranslated novels—Mario Vargas Llosa and Guadalupe Nettel, for example.

Of course, I plumb the classroom experience for poetic narratives. Teaching becomes stranger and lonelier as I age. I am now older than many of my students’ moms. My reference points, cultural and historical, are unknown to them. As Proust wrote of a painter mourning the death of his contemporaries: “[With the death of] M. Verdurin [Elstir] saw disappear the eyes, the brain, which had the truest vision of his painting…it was for him as though a little of the beauty of his own work had been eclipsed, since there had perished a little of the universe’s sum total of awareness of its special beauty.” Only our peers understand where we are coming from.

I try to get them excited about obscure words in English, not just those which are “common” or “useful.” When they ask me if a word is important or necessary to know, I always say “absolutely”! Of course, when I tell them I’m a poet, I’m mostly met with blank stares. (Of course, this also happens at dinner parties with native speakers. I find many people are uncomfortable around poets. They don’t like poetry and feel they should, or they don’t like poetry and don’t want to pretend, or they like it but worry they won’t be able to say why, or they only resonate with what are disparagingly referred to as “Instagram poets,” or they wonder why anyone would choose to do something so unremunerative or that seems to make so little impact on the world…) Every once in a while, though, I’ll meet a fellow poet from another culture and they’ll share their favorite poets in translation, or they’ll share their own work with me. That’s a special brother/sisterhood.

Jon Riccio is a PhD candidate at the University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Writers where he serves as an associate editor at Mississippi Review. Recent poems appeared in Pattern Recognition and Maryland Literary Review. The poetry editor at Fairy Tale Review and a former Poetry Center intern, he received his MFA from the University of Arizona.