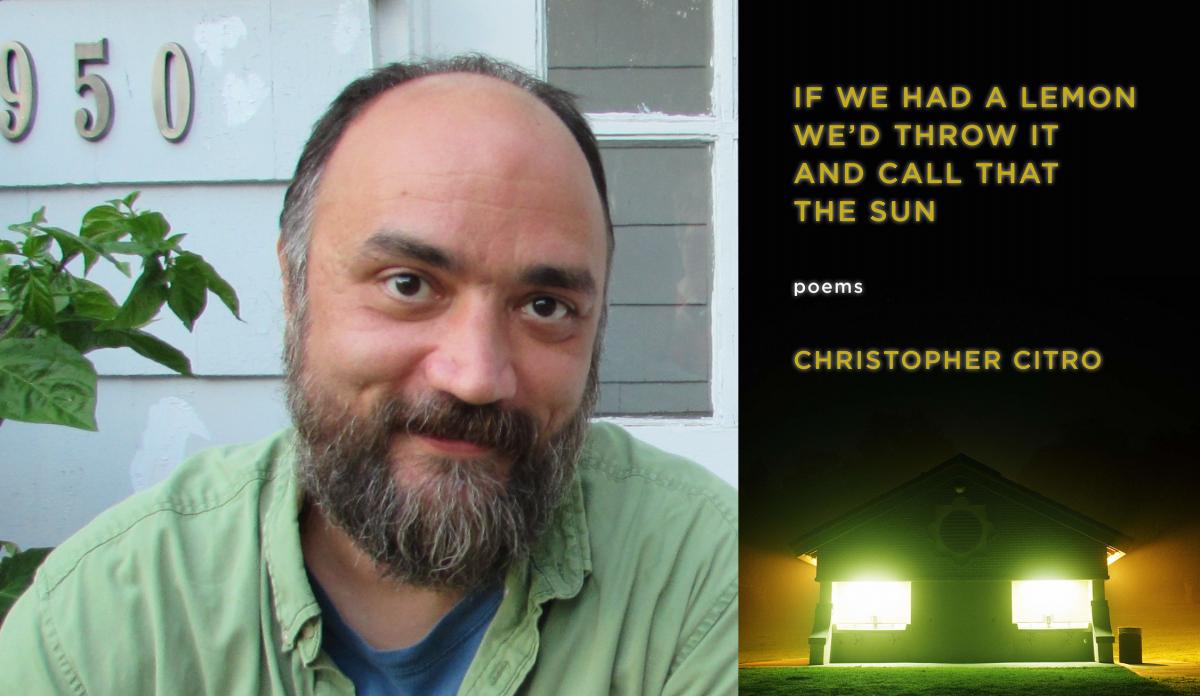

Christopher Citro is the author of If We Had a Lemon We’d Throw It and Call That the Sun (Elixir Press, 2021), winner of the 2019 Antivenom Poetry Award, and The Maintenance of the Shimmy-Shammy (Steel Toe Books, 2015). His honors include a Pushcart Prize for poetry, Columbia Journal’s poetry award, and a creative nonfiction award from The Florida Review. His poems appear widely in literary magazines and journals such as American Poetry Review, Ploughshares, Iowa Review, West Branch, Gulf Coast, and Alaska Quarterly Review. His writing has been anthologized in Best New Poets 2014, New Poetry from the Midwest 2019, and Best Microfiction 2020. He lives in sunny Syracuse, New York.

Jon Riccio: Each time I open my signed copy of If We Had a Lemon We’d Throw It and Call That the Sun, I’m greeted by your inscription inside a hand-drawn rendition of the titular fruit. Bravo not only on your book, but on the sketch’s accuracy of a pedicel (otherwise known as the lemon’s nub). That’s a poem word for sure. I remember my excitement reading “Saving Myself (For Something)” and “We’re Actually Fabulous” in The Ochre Issue of Fairy Tale Review, the second poem ending extraterrestrially—

If a stranger arrived here from an unknown

land and saw a project manager walking down

the street holding an umbrella in one hand

and a hot cup of coffee in the other, his head

would explode. If he had a head. If he only

had tentacles, those would explode.

It was great encountering the astronomy-steeped poems in If We Had a Lemon . . . . Whether it’s

A summer night a thousand miles wide.

Little lights traversing the distances

at the height of our eyes, at the speed

of our hands. My head a spaceship

moving through it. My body a planet

running on another planet, (“On a Foreign Planet Surrounded by Sugar Maples”)

or

The doorway to all

the stars that have ever been just the other side

of [astronaut’s] skulls and each one turning, raising

a camera to focus back in on the earth. (“Holding My Head in Both My Hands”)

galactic reverence flickers throughout. How else does Milky Wayfaring extend to your work?

Christopher Citro: Hi Jon. First off let me thank you so much for this opportunity to chat and for your kind and thoughtful comments and questions. My new book and I are honored by the care and attention you’ve given us. And thank you again for having published those poems of mine years ago in Fairy Tale Review. I turned cartwheels around the living room when I got that acceptance.

I’m responding to your questions from a cabin high up in the Adirondacks where we’ve come to spend our summer vacation, so if I throw in a few references to black bears and moose, you’ll understand why. Not that we’ve actually seen either of these creatures, but yesterday before skinny dipping in a trout brook we did come across a bright burnt orange salamander with black-ringed red dots on its back. Which was about as good as a moose . . . maybe even as good as one-and-a-half moose.

The night sky up here is particularly star-laden. Last night I could see the Milky Way stretching

between two massive shaggy spruces off our cabin’s back porch. At one point I thought I saw a flying saucer. I realized it wasn’t a spaceship when it landed next to my bourbon highball on the deck and winked its butt-light at me.

I’ve been in love with the night sky, with astronomy, with the concrete poesy (I think Lawrence Ferlinghetti said that) of black holes and quasars, since I was little. Isn’t everybody? Stepping outside to gaze up at the night sky never gets old, and it’s no surprise that references to the wider solar system, our galaxy, to life, the universe and everything come up again and again as I compose my poems. Long ago I fantasized about becoming an astronomer, or a quantum mechanic, and that fascination has never dimmed. I also know that when I’m writing poems, my mind’s eye will sometimes lift off from whatever I’ve been focusing on here on earth to get a bird’s eye or even a cosmic eye view. I don’t know why my brain does that, but I’ve learned to relax and go with it.

In this first poem you quote, “On a Foreign Planet Surrounded by Sugar Maples,” I fell into a memory of playing in the front yard on a summer night, lightning bugs like little stars blinking on and off. I love that thing that can happen where focusing closely on something small, like a bug, can make you feel like a giant (because small things are also sometimes big things that are far away to our eyes). When I was little I’d hold a toy plane under my eye and make believe I was high in the air flying through our house. In the memory that underlies this first poem, the recollection of (apologies to all lightning bugs) rubbing a firefly on my clothes to draw with that glowing crayon (golly kids can be brutal to nature, I’m feeling so awful just remembering doing this) opened the door of my imagination to reinhabit one of these moments. I could move my mind’s eye from that nearby glow to the lawn at my feet, the pine trees above me, and the stars flickering away against the dark cave of an Ohio summer night. And when my mind’s eye turned far enough to the left, it saw through the picture window into our house—another flickering glow, this time of the blue TV light—and at that moment in my memory my parents were still alive, doing something so mundane as watching the tube. My parents have been dead for years. I wish I could turn back time and have a boring old summer evening when we all felt there was so much time left in the world that we could squander it watching Jack Tripper roller skate through an episode of Three’s Company. Something about the scale jumps of the very small (bugs and the boy-me) and the very large (huge trees, stars, mortality) drove this poem’s discoveries.

In that second poem, “Holding My Head in Both My Hands,” I began, as I often do, in a moment of desperation, of panic, of confusion. This moved on quite naturally to the things we do in our lives to try to make us feel like we’re in control, or at least not wildly out of whack. I remembered hearing one of the Apollo astronauts say that as he lifted off—surely a moment of profound uneasiness no matter how much of a cool as a cucumber test pilot you are—he realized he was sitting at the top of several thousand tons of exploding liquid hydrogen in a tiny control cabin designed and built by the lowest bidding contractor. *Gulp.* Can’t you just feel your spine contract at that thought? This brought to mind some of the first photographs of earth, which were taken by those astronauts, and the beautiful irony that in that moment of lifting off farther than humans had ever gone, one of the most meaningful things they did was to turn back around and look at where they came from. This Pale Blue Dot. The humanness of that gesture just snaps my heart in two.

JR: I loved your summary of New York City in “We Might As Well Be Hovering”—

[It] would be squat if not

for the granite beneath all those fashionable

people and even the mole people who live

in the subways and have all-white eyes.

This is a counter-color to the “The Man-Moth’s” orbs, which Elizabeth Bishop describes as “all dark pupil, / an entire night itself, whose haired horizon tightens / as he stares back, and closes up the eye.” Bishop situates him in “the pale subways of cement he calls home,” the lucky onlooker eligible for his tear, a trinket “cool as from underground springs and pure enough to drink.” The gifts in “We Might As Well Be Hovering” are stored in Norway’s Svalbard Global Seed Vault, should humankind resort to doomsday gardening. Do you see ecocritical threads in your poems, wherein the mole-people types or the collection’s frequently appearing bees become Earth’s caretakers?

CC: Thank you for noticing these threads in my poems. I often think that I am, at least sometimes, a bit of a nature poet, though I suspect that few people see this. I am in love with the natural world—again, as with the cosmos, isn’t everybody?—and I live in an almost constant state of being paralyzed with fear and disgust at the countless ways my species has trashed the joint. How lovely it would be to live back in the time when the earth wasn’t so wrecked by the results of our technology and thoughtless greed. Just yesterday I read, “Over the past fifty years, bird populations in the United States and Canada have fallen by 29 percent.” (“A Searing Bolt of Turquoise,” Christopher Benfey, New York Review of Books, August 19, 2021.) So there’re one-third fewer birds now than when I was a baby? Cripes. But at the same time, this is the one life that I have to live, and it’s now, on an earth that’s in many ways fucked completely, and in many other ways still managing to keep trucking along. All of these perspectives will find their way naturally into my poetry, and I hope will speak to the different feelings that readers have about our planet.

In the poem you quote, the voice begins in a moment of distress. In this poem, my mind’s eye shot down into the ground, into a place where we might find stability, literal and emotional. I’d been reading some natural science books where people spoke casually about the kind of stone below their town, and I’d thought to myself, “Who knows what kind of stone is under their town? Who are these people? I have no idea what stone is under me right now. The only place that I know that about is New York City, which was built supposedly on granite.” That led me to imagining being under NYC, which brought up a book I’d read as an undergraduate: Jennifer Toth’s 1993 The Mole People: Life In The Tunnels Beneath New York City. That prompted the lines that you quoted. As the poem continues on its journey towards the international seed bank in Norway, a non-metaphorical preparation for doomsday, the haunting image of those blank eyes lingered as a kind of loss, which helped me discover the poem’s final lines.

To answer your question more succinctly: yes, I can easily fantasize about the earth being taken over by bees. Let’s let the bees and the moose and the black bears and the felines have a go for a while. They’re unlikely to screw it up as badly as we have.

JR: Staying the European trek,

Men travel

to Switzerland to throw themselves off peaks

in special suits like sugar glider squirrels—

passing through valleys, above fields so green

they sting the eyes—as we do in dreams. (“To Keep At Least Partially in the Air”)

Halfway through, the poem shifts from frivolity to devastation—

And the stories

of how cancer patients really die

that hardly anyone talks about or hears

because they’re family stories or seen only

by professionals, can’t get to us now.

They really can’t.

These contrasts are resonant because we’re afforded security with “can’t get to us now. / They really can’t.” Do you think there’s a difference between safety and protection?

CC: Like most people, I spend an inordinate amount of time staring at YouTube. I’d heard somewhere about this one-piece suit that people put on and then jump from tall places and fly like hang gliders. I found a video of someone doing this in Switzerland. At one point they shot under a stone arch on some mountainside . . . or maybe I imagined that. Absolutely beautiful and absolutely bananas as far as safety goes. This lyrical, thrilling bit of extreme sports got me thinking about mortality. Almost as if some mom inside my head saw me fantasizing about throwing myself off a mesa wearing umbrella wings under my armpits and said, “Now you just stop right now. You’ll put your eye out. Cripes, you’ll put your whole brain out!”

I read Ernest Becker’s Denial of Death at probably too young of an age, and certain things about it have never left me. Thinking about how, instead of just being fun, these foolish and goofy things we do in our lives that provide thrills while also potentially killing us stone dead in a second, speak to something about how it feels to live under the burden of our own mortality, of knowing we will die. The poem starts with metaphors for how spring makes us feel like everything is going to maybe be okay, as if we have an invisible barstool under our butts ready to catch us safely whenever we drop. This is the opposite of how I feel at the end of a long Syracuse winter, where any thought, no matter how happy, can leap into darkness and despair when you look out of the window at yet another thick gray sky and crud-covered snow like those burnt potato chips at the bottom of the bag that you plan never to eat, then when you finish the whole bag can’t handle the idea that they are all gone, so you let yourself eat one and then make that yuck-face they put on the side of solvents to let people know they’re poison.

In my first book, The Maintenance of the Shimmy-Shammy, there’s a prose poem, “Those Daring Old Men,” with the line “Life’s too precious to slowly waste away protecting it year after year.” On one level that’s paradoxical, if not actually stupid. On another level I think it speaks to the reason why we do some of our more irrational pastimes. And by “we” I mean our species. Personally, I get nervous stepping out of a shower and grab onto the soap dish to try to keep from falling and dying on the bathroom floor beside my confused cat. I speak as someone with zero experience in extreme sports. This winter I gripped the stair rail at home so hard I ripped it out of the wall.

Speaking from the perspective of this vacation cabin, last night I sat out on a chaise lounge on the screened porch sipping a Manhattan with my cat on my lap (yes, we brought our cat with us to the Adirondacks). At one point after midnight, she and I heard a loud thud from under the cabin. Then a second thud. She turned her head to me electrified, her face stretched taut, her pupils big as frisbees. I looked back at her with my pupils the size of frisbees. I petted her and murmured something about: “There-there girl, those nasty bears can’t get at us.” What actually lay between our tender flesh and the slathering bear jaws just out of sight in the thick night? Millimeter thick window screens, and—well, that was all there was. Were we protected? Nope, not by much. Did I feel secure? With my girlfriend sleeping away in the upstairs loft bed, with the soy candle flickering on the picnic table nearby, with my black cat in my lap clearly calmed by my petting her, yes I did feel secure. Foolishly so, but I felt it. How the mouse or whatever it was thumping about under the cabin felt, I cannot say.

JR: Your opening poem “It’s Something People in Love Do” references the Marx Brothers’ 1940 film Go West, while arctic shoe-eating in “How We Make It Home Eventually” reminds me of Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925). “If it wasn’t for film noir, I don’t think / we’d take autumn like we do, letting it roll over us” (“Removing the Butter Dish from the Fridge with a Sense of Urgency”) is the cinematic icing on Lemon’s cake. What are your favorite qualities of early Hollywood movies, and how do they shape your poems?

CC: So you’ve noticed that I have a thing for old movies, eh? Film noir, pre-Code movies of the 1930s, screwball comedies, silent films—especially the whacked-out German Expressionist kind—I can’t get enough of them. And since I gave up watching television way back in high school, which is a fair few months ago now, they’re just about the only things I watch.

What do I love about them? The rapid-fire witty dialogue of the 30s films, the non-dumbed-down sexuality and sensuality of the pre-Code movies, the jazz music, the fashions, the moody dangerous atmosphere of film noir, the Joan Blondell, the Hugh Herbert, the Marx Brothers, the W. C. Fields, the Three Stooges, the Laurel and Hardy, the William Powell, the Myrna Loy, the Norma Shearer, the Katharine Hepburn, the Peter Lorre, the James Whale, the Cab Calloway, the Cary Grant, the Fred Astaire, the Mae West, the Humphrey Bogart.

Back in high school, the powers that ran the joint got so annoyed that our radio station (the one

really cool thing about my rural high school) had become a meeting place for all the freaks, that they completely changed the format to oldies. No more Bad Brains and Dead Kennedys. They kicked out all the student DJs and replaced them with folks from the local community. All old people. It was heartbreaking. Later the little sister of my best friend started tuning the new-format station in, digging the old big-band music, the 30s jazz. And because I thought she was nifty, I started paying attention to that kind of music. I found I loved it, especially the attitude of it all. When she turned me on to the road movies of Bing Crosby and Bob Hope, my life-long love of old film burst to life.

How does my love of old movies shape my poems? That’s a good question. I’m someone who never plans what I write, every morning I sit down to write I do what I call radical free-writing: basically just letting the jazz or ambient music get my brain into an energized space. I read poems to get inspired, and when an image or a phrase or voice comes to me, I just start scribbling. Whatever happens happens. And since I watch old movies so often, images from them are likely to come out in my poems . . . along with news headlines, things my girlfriend and I get up to, stuff my cat’s done, our tomato garden, facts from the science and nature books I read, whatever.

In the poem that starts my second book, “It’s Something People in Love Do,” I was reading some Heather Christle for inspiration, copied out the lines that form the epigraph to the poem, and something about setting fire to things you don’t normally set fire to called forth that wild scene at the end of Go West where the Marx Brothers burn up a train in the process of keeping it going. I don’t know about you but that’s both a funny thing to watch and absolutely some sort of metaphor for a whole bunch of things in life, in our personal emotions, in relationships, in ways in which we sometimes destroy something out of a frantic attempt to live it, to keep it alive. It ain’t healthy, but it’s touchingly human. As the poem came alive as a sort of ekphrastic recreating that scene, it felt natural after a while to make the jump to the love relationship of the speaker of the poem. Plus the rhythms, the tempos, the sounds of the locomotive train from the film got into the poem as a motive force, and once that happened I as the writer was just along for the ride! I knew the poem was over when something happened that really surprised me—which is one way I know that a poem has both come to life and when it’s ended—with the lines “Then we / could clean each other’s face with our tongues. / It’s called kissing. People in love do it.” With the paratactic short sentences of the last line, like two blasts of locomotive steam releasing, I knew this train had pulled into the depot. Or shot off a cliff. Either way the film was over. Time to shake the popcorn kernels out of your shirt and shade your eyes when the house lights come back on.

We haven’t watched any old movies yet at this cabin, but it’s not hard to imagine trying to live here through a long hard winter, getting to the point where we’d have to cook and eat a boot, if no moose came by and offered to get in the oven. It’s a tiny oven. The moose would have to really crouch down.

JR: I enjoy speaking with poets based in Upstate New York, as my dad’s family resides a half hour outside Albany. Though “Beaver Lake” is located in Onondaga County, its farm “where they’ve carved the corn maze already” could be anywhere. Its “pumpkins with their faces / painted on smile at you in the day and at night / change back to just regular pumpkins.” Before this on-off happiness, you ask “What’s fun about being yourself?” Is If We Had a Lemon . . . a collection-length answer?

CC: Upstate New York has its issues, of course—I see one more Don’t Tread on Me flag and I’m

going to start projectile vomiting—but it’s also a beautiful place. We’ve been here for the last nine years, landing in Syracuse after graduate school in Indiana, without knowing anyone. I must say that it’s great being smack in between the Finger Lakes and the Adirondacks—it took just three hours to drive to this cabin which feels like the middle of nowhere—plus just five hours to the Atlantic coast. Autumn is particularly beautiful, and my poem “Beaver Lake” is a sort of homage to that time of year, in addition to being an homage to Liehs and Steigerwald, a local German deli whose bologna “actually / gets you excited about bologna.” I just finished a poem recently with an homage to our local Polish restaurant called Eva’s European Sweets. Their potato pancakes, as my

oldest brother would say, “will make you give back shit you didn’t even steal.”

Is my new book a collection-length answer to the question in that poem, “What’s fun about being yourself?” I don’t know. I like that idea, though. In that poem, the question functions ironically, coming as it does after the bits about, if I run regularly my legs hurt and if I let my exercise regime go, then everything starts hurting. Yippie being in one’s forties! (Can you feel the sarcasm in that?) But still, I do write my poetry out of an enthusiasm for life, even the lousy bits of it. It’s one of the things I love hearing from readers, when they say that my poems make them feel energized about the simple details of life, make them look at things in a new way, make them excited for their day. My golly, to have helped create the context for someone to feel that! Because of some words I arranged on a page? That’s one of the greatest things about being on planet Earth that I know.

So far this week at our little Adirondack cabin, I haven’t written much new poetry, but I’ve been filling the interior coffers up with images that might come out in some future poems: my girlfriend in her cowgirl hat crawling around on the huge boulders in the trout brook, ferns blowing in the breeze down the hill out back, furry gray lichen everywhere, restaurant moose heads, the Milky Way like a Band-Aid across the night, the cabin’s lemon-themed tablecloth, daisies like open eyes, the burnt orange salamander, the laughably Disney-ish mushrooms all over the place, pines like intelligent giants, fog that moves like a motorcycle gang, the air like breathing when you were four years old. Paper bark birch. The laundry dryer that plays Schubert.

JR: One of my greatest challenges is writing about tenderness. Kindness I’ve improved at, but the Warm T eludes me. This is why I’m doubly impressed with the ending of “One Light in a Field of Other Lights”: “Every little plane in the sky— / especially at night—I want to reach up and / give a little push to help it on its way.” Another excerpt I should memorize is

Let go and see where falling takes you. Here

I’m watching you chop carrots and there’s all

these gold coins piling up beneath your fingers.

You’re making me feel rich. (“I Smell the Dirt All Around Me and Above”)

What are the fundamentals of tenderness-poetry?

CC: Jon, how very kind. Thank you for saying this about my poetry.

In the first poem you quote, “One Light in a Field of Other Lights,” it begins with me being

annoyed by summer being half over before I’d even begun to enjoy it (Syracuse weather, again) and some noisy next-door neighbors. I let these crabby emotions out and then made a conscious attempt to bring in a little tenderness to the poem, which lead me to remember a discussion that my girlfriend and her dad had about a time he was helped by some strangers while on a summer-long bike trip when he and his other daughter biked over 1,500 miles around most every state park in Missouri. <https://www.news-leader.com/story/sports/outdoors/2014/05/14/dad-daughter-plan-mile-bike-tour-state-parks/9093465/> Fireworks were going off over our heads as he spoke from the back seat of our car. His story of kindness among strangers helped me find my way to that final tender image of reaching up to wave at plane full of strangers, to help them on their way.

In that second poem, “I Smell the Dirt All Around Me and Above,” the opening lines come from a memory of how doing something as mundane as chopping carrots for dinner with the person you love can make you feel over-flowing with thankfulness. It seemed like a nice way to start a poem with such a melodramatic, morbid title. As that poem progresses through images of caves, and remembered childhood research reports, and some actual spelunking I did years ago, it ends with the surprise of “When someone loves me enough / to send a communication these days / I write or telephone right back.” I don’t always do this. (Sorry Dustin!) I guess that’s the difference between the speaker of a poem and the author writing it.

When I think about tenderness in my own poetry, I find several avenues open before me. On Avenue A I’m a total mushy goofball in real life, if you really get to know me, and I trust you, and we’re alone. Because of this, lots of the poems I write turn out to be just happy and sorta mushy all the way through. I recognize that these tend not to rise to the level of “art,” since narrative arts, including lyric poetry, need some sort of conflict to be interesting, to constitute an aesthetic journey. Music, painting, dance—these can get away with being joyful all the way through, but I don’t know that a poem can. So for me, I write those goofy, super-tender poems because they naturally come out, but I don’t type them up and revise them. When my mushiness comes out mediated by something else, by some difficulty, some sense of conflict—and if it’s a good draft—I might type it up and try to revise it into shape. I used to not want to let any of this kind of tenderness out in my poems, but over the years I’ve realized that it’s ok. It’s who I am.

Down Avenue B we get to something that I took to heart from my MFA program. My teachers kept talking about empathy as a quality of the best creative writing. At first I was resistant to hearing this because I thought it meant you couldn’t be angry for righteous reasons, you had to be so sweet and understanding and Zen-like all the damn time. Blech! That seemed to shut out too many other emotions. And it seemed fake, like a put-on. Well, the misunderstanding was mine. Eventually I came to grasp the difference between sympathy and empathy, that sympathy invites me to be on a character’s side while empathy just means that I am recognizing that the other person is a human being (even if they are a monstrous, terrible human being). I got it through my thick head that one of the reasons we still read and love Shakespeare is that his characters are treated with empathy, even the absolutely villainous characters like Iago are presented in their wide range of humanity. I noticed that in the loftiest art—Dostoyevsky, Shakespeare, Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, James Baldwin—there’s always an element of empathy. So that is something to shoot for if you are aiming for Art with a capital A. I’ll admit that I don’t always feel empathy in my real life. But in my writing, I consciously try to aim for it. And when I come close, it’s when I’m writing my best. It’s also when those moments of tenderness come out.

And as long was we’ve got the car packed and we’re headin’ into the high peaks, here’s an Avenue C: the beloved poet and writer Jim Harrison once said, “The novelist who refuses sentiment refuses the full spectrum of human behavior . . . . . I would rather give full vent to all human loves and disappointments, and take the chance on being corny, than die a smartass.” I’m with Jim Harrison on this one.

Ok, before we squeeze out of the Toyota at our destination, let’s take a last quick trip down an Avenue D: remember Otis Redding? Remember when he sang: “It’s not just sentimental / She has her grief and care / But the soft words they are spoke so gentle / It makes it easier to bear / . . . /

All you got to do is try / Try a little tenderness.”

JR: Another dynamite quality of your writing is the ebb and flow between younger and present self. “We Are Many People Some Okay” does this flawlessly—

I’m ten years old. I can’t

expect you to have noticed. It happens in an instant.

Then I grow back up again which means I try to

use my mouth to explain to you what’s happening

and it’s not your fault.

“Otherwise Inexplicable Animation to the Forms Above” reverses the chronology—

Today I replaced the plastic sugar bowl with

a glass peanut butter jar so we don’t get killed

by our sugar bowl. I can honestly say

my 18-year-old self could not have predicted this.

It’s time traveling, the poet’s past as reactor output. What were some unexpected discoveries you made mining your continuum? How did they translate into poems?

CC: Oh man, Jon. Doesn’t this happen to us all! We’re all going around our lives being so adult and smooth and groovy, and at the same time there are so many different younger versions of ourselves in there screaming at our little sister, or crying because we dropped our popsicle, or running through a backyard sprinkler, or talking with an ex who maybe isn’t even alive anymore. We’re those people at the same time that we’re our current selves too. We jut back and forth without knowing it, without an ounce of effort. This happens to me all the time and is often the source of jumps and surprises in my poems. Most of the time we’re not aware when earlier versions of ourselves are in control. Some of the strange stuff we do is because one of those earlier versions of ourselves has come close enough to the back of our eyes and mouth and has temporarily taken over the PA system. Sometimes this is great. Sometimes this is not great.

In the second poem you quote, “Otherwise Inexplicable Animation to the Forms Above,” it happens because the adult version of me drives an SUV, has a membership at Costco and a salad spinner. (I remember specifically ridiculing each of these as a snot-nosed teenager). For a while we were trying to replace plastic storage jars (BPA and other chemical nastiness), so I switched out the plastic sugar jar with a reused chunky peanut butter jar. I was trying to help us not die. And this felt like one way to do that. It also felt like a hell of a goofy thing to do, something which my devil-may-care eighteen-year-old self would have found laughably contemptible. And he’s still inside of me, frequently annoyed, smoking Camels behind the Kenston High School dumpsters.

In the moment from the first poem you quote, “We Are Many People Some Okay,” I’m writing about something that also happened. My relationship with my mother was a complicated one. Patience was not, let us say, one of her virtues. Growing up with her made me jumpy about being criticized and attacked when doing some complicated task that I’m not necessarily already awesome at. Back when I was little, I got so that I’d wait until late at night to do my chores, when she was asleep and couldn’t scream at me. (My mom was also a sweetheart, but in this poem I was remembering this part of her.) As an adult I can get all tense and freaked out if someone observes me closely while I’m doing something I might mess up, like goofily trying to scoop diced potatoes out of a steamer with too small a spoon without spilling them all over the stove. That real-life moment created the inciting incident for this poem about how we’ve got all these people inside us. Sometimes it’s awesome. Sometimes it’s, well, challenging. Including for the other people around you. They just see the current version of you. They probably don’t realize that the person speaking is a ten-year-old you. And that the person you are speaking to might be your mom, who isn’t even there. How many of us are scared to do X, which we’re perfectly adequate at, because of something someone shouted at us on the playground when we were eleven? How many of us are fighting with our current lover because of something three lovers ago said to us?

Remember the great Noël Coward play, Blithe Spirit? I love the scenes early on when the writer (Charles) first sees the ghost of his dead wife (Elvira) in the same room with his very much alive wife (Ruth). He’s freaked out, frightened, trying to carry on a conversation with both people. He can see his dead wife, but his alive wife can’t. The ghost wife is having a mischievous ball causing all this conflict, while the current wife is confused by all the irrational stuff her husband is saying apparently to her. And he’s being rational, just trying to engage the two different people that he sees.

CHARLES (moves a couple of paces towards RUTH): Elvira is here, Ruth—she’s standing a few yards away from you.

RUTH (sarcastically): Yes, dear, I can see her distinctly—under the piano with a zebra!

CHARLES: But, Ruth . . .

RUTH: I am not going to stay here arguing any longer . . .

ELVIRA: Hurray!

CHARLES: Shut up!

RUTH (incensed): How dare you speak to me like that!

CHARLES: Listen, Ruth—please listen—

RUTH: I will not listen to any more of this nonsense—I am going up to bed now, I’ll leave you to turn out the lights. I shan’t sleep—I’m too upset. So you can come in and say good night to me if you feel like it.

ELVIRA: That’s big of her, I must say.

CHARLES: Be quiet—you’re behaving like a guttersnipe.

RUTH (icily): That is all I have to say. Good night, Charles.

RUTH walks swiftly out of the room without looking at him again.

JR: Your social media features the book surrounded by photogenic lemons, contributor-copy mail runs, and what I refer to as the Han Solo Hoth jacket. I think of the Marianne Moore paraphrase that Diane Seuss used when she described you “writing poems . . . that dogs and cats can read.” Tauntauns too. These pictures are joined by postings of fellow poets’ collections, Sarah Freligh, Laura Donnelly, Eric Roy, and Jennifer L. Knox, to name a few. Without a doubt, such generosity carries over to teaching. What are the main emphases of your workshops?

CC: Thank you for that kind comment. I dearly love teaching, whether it’s at a university, at the Downtown Writers Center here in sunny Syracuse, in writing conferences such as the Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing, the Kettle Pond Writers Conference, or the upcoming 2021 A Literary Bit Of Literature Festival in Oxford, Mississippi, or for my private students and private classes I teach online. Some folks say that teaching saps their writing energy, and while it certainly can be tiring, I find that it energizes me for my own writing in so many wonderful ways. In my workshops I emphasize many things, some of which include the idea that we grow as writers by focusing on our strengths, that the elements of writing craft are learnable, that creativity best comes out to play in an accepting, encouraging atmosphere, that one of the best ways to be inspired is to read and be absorbed by great poetry, even outside thinky analysis.

In my teaching I try to share with my students as much awesome poetry being written now as I can, along with inspiring examples from the past. I also love creating writing prompts, and I fill my sessions with these, created in relation to the pieces we discuss. Here’s an example, from the advanced poetry writing workshop I taught last spring at SUNY Oswego, where we read books by Vievee Francis, Albert Abonado, Paige Lewis, and Alicia Mountain.

In Vievee Francis’s book, Forest Primeval, there’s a poem called “A Flight of Swiftlets Made Their Way In,” during which the speaker imagines her body as a cage, a cave, a tomb where these myriad feathered creatures have perched (“I have never been whole / so there was room.”). At first she considers snapping their necks, but at the end she’s been changed by them, she’s considering taking flight herself. The birds take over the poem, the speaker’s body, with their pounding wings, as the poet scatters the word beating all down the page. It’s a breathtaking moment in a breathtaking short poem. For my class, I shared with them this simple prompt that I wrote:

Write a poem in which you have an interaction (real or imagined) with some part of the natural world (animal, vegetable, or mineral) and in which you are changed, metaphorically, in some way, e.g. the speaker in Francis’s poem becoming a cage, a cave. Don’t know where you are going to end up ahead of time, just follow the figurative language through to see where it goes. For an added twist, experiment with the written space, with the way the text is arranged on the page, to help direct the tempo of the reader’s movement through the poem in ways that foster the emotion.

JR: The transition from “In Small Significant Ways We’re Horses” to “Peaks Shot with Hairs of Lightning” makes the perfect seat-belt click. “Some people take / anything goes, the sound of breath, the sweetness / of a golden raisin, the earthiness of rolled oats.” closes the former, “Oatmeal and yogurt first thing. Fruit if there’s fruit.” beginning the latter. A similar click occurs between “To the Dirt Which Will in Time Consume Us All” and “A Mud Puddle Shaped Mud Puddle”—

You tipped

your cowgirl hat and gave the subsiding hillside

the finger with your other glove, its cowhide

yellow like a star down in our yard.

which is followed by the beginning lines “I waited for the stars to drop down, / a handful at least—is that too much to ask— / and spin a slight constellation in front of me.”

How important were such “clicks” in your first book, The Maintenance of the Shimmy-Shammy?

CC: How delightful of you to notice that, Jon! Not everyone reads poetry books from front to back—I do sometimes—but I like to order mine as if they were being read that way, so the book, hopefully, because of its structure, becomes itself a work of art.

When I was in my MFA program at Indiana University, I brought in an early draft of my thesis (the heart of my first book, The Maintenance of the Shimmy-Shammy) divided into four sections based on its four main themes: childhood, dating, settled relationships, and making art. My advisor, the wonderful Catherine Bowman, encouraged me not to have the sections clumped by theme, instead to break these up across the various sections, so readers could be delighted and surprised by a mix of imagery instead of being boringly able to predict that everything in section one, for example, would be about childhood. And golly she was right!

Around the time I put together the later revised versions of this manuscript, I was reading through John Berryman’s Dream Songs, in addition to listening to as many recordings of him reading them that I could find. In the books, the Dream Songs are varied by theme, but in his live readings of them he’d make announcements between poems such as, “Enough with the religious Songs, now let’s have some political ones.” That seemed wise to me. Listeners have only once to hear a poem, and the lines go by quickly, so they can use the scaffolding of knowing that the next few poems are about travel or sex. But in a book where readers can take as much time as they want, and which is also an experience they will hopefully return to and should stand the test of time, you don’t need that scaffolding. It becomes stifling to the reader’s journey through the book.

So for both of my published books of poetry I’ve structured them the same way, only including poems on a small number of themes which speak to each other in interesting ways, but then linked poem-to-poem on the level of image or word, e.g. if one poem ends with a star, I’ll see if I have another poem that starts with a star or something in the sky at night. Readers don’t need to, and won’t usually, notice this, and if they’re jumping around it won’t matter. If they’re moving page by page, hopefully it’ll make little chimes go off in their head, little resonances vibrate in their heart. That’s one of the things I rely on to help make my books feel like a book, especially given that my books are never written as pre-imagined projects. I’m unable to write poetry that way. They’re all put together out of whatever individual poems I’ve written up to that moment.

Of course I attend to other things when I put together a manuscript—for freshness, varying poems

by tone, by dominant pronouns, by forms—but the “click” you are talking about is precisely that little echo/resonance that I hope stitches my poems together. (Golly, I’m mixing my metaphors here aren’t I?)

For the first pair of poems you mention, “In Small Significant Ways We’re Horses” and “Peaks Shot with Hairs of Lightning,” in my manuscript-building notes I have written down between them simply “oats”—that’s the thing that clicks them both together. I hope they are pleasingly varied at the same time by the fact, in my opinion, that the first is upbeat and second is more somber, the first is mostly You and I pronouns while the second is mostly We, the first is very nature-y, the second is more about love and office work. They both have lots to do with food though. In the second pair of poems you quote, the click is because the former poem ends with a star and the latter poem begins with a star. Seems sort of silly really, but hopefully when a reader journeys through the book it doesn’t call too much attention to itself, instead readers will just have the inner experience of looking into the night sky, seeing stars shimmering from the end of one poem to the beginning of another.

At one point in the years of revising and changing this manuscript, it rained in the middle of the book. I’d gathered poems and ordered them from dark clouds gathering on the horizon, the sky above getting heavy, the first few raindrops falling, full storm bucketing down, the deluge thinning, sun coming out, the swept-clean air of after-rain. I scribble outside a lot, often about the weather, so it happened that I had enough poems to create this sort of arc, though they were written apart and over years. I liked the idea of there being a rainstorm in the middle of my book, that maybe only I would ever know about, but which would happen in the heads and hearts of the readers. Sadly, it became the right thing to do to change the poems and the order as I continued to revise the manuscript, but I still remember that at one point that thunderstorm shook the pages of If We Had a Lemon We’d Throw It and Call That the Sun.

JR: Lemon on, Christopher! The sentences “We all have front doors.” (“That’s Why They Invented Cheesecake”) and “It’s a new world and we’re new in it.” (“The Sweet of Being Made Right”) were tied for how I’d end the interview. Stepping into or through involves curiosity, the element that keeps me writing. What’s the most curious you’ve ever been about a building? Have you written it?

CC: Skinny dipping yesterday in the brook behind this Airbnb got me remembering the time I once snuck into a derelict building I was curious about when I was an undergraduate. At time of going to press, I have not yet written about this in a finished poem, but there’s always tomorrow.

At Ohio University in the early 1990s, behind the philosophy department, there stood a large, abandoned building with painted-over windows. Nobody ever went in. Nobody ever came out. At this time, I had a circle of friends which included a guy we called Naked Boy, because he liked to take his clothes off. The rest of us did drugs, he took his clothes off.

In addition to my philosophy classes which I took for my major, I was also attending photography classes—learning darkroom technique, mixing trays of acrid chemical solutions, standing under those spooky amber lights wearing long blue rubber gloves—and my friend used to ask me to take photographs of him without his clothes on: reflected in the convex mirror of the handle of his bathtub, striding confidently and buck-ass nudely through the college gates (at 4:30 am), both of us moving quickly so we wouldn’t get arrested.

One day Naked Boy and I decided to sneak into this abandoned building, right there in the heart of campus with people walking around it, traveling to and from class. He wanted me to photograph him inside of it. So on a sunny afternoon, we did just that, crawling in through a basement window we found unlocked (what’s the statute of limitations on trespassing in the state of Ohio?).

We made our way past toilets with no doors, lockers vomiting twisted, dust-covered shorts, sneakers, broken exercise equipment. We walked slowly through shadowy concrete halls accompanied only by the sound of our echoing footsteps. From above us long fuzzy sheets of some sort of white fabric hung down in strips we brushed our way through, stepping over dissolved piles of white fluff on the floor. We came out of what felt like a tunnel to find . . . a huge empty swimming pool. This eerie space was pretty dark, except for the sharp beams of angled autumn light piercing in through holes in the painted grid of windows above the high dive platform at the deep end.

Naturally the next thing that happened was that my friend took all his clothes off, climbed up the ladder to the tallest platform, and stretched his arms out in a Jesus pose against the glowing, paint-peeling windows high up behind him. I set up my camera tripod beside a 6 ft. mark on the poolside and tried to remember the techniques I’d been taught for photographing someone who’s extremely backlit. All around us the empty pool echoing our hushed voices, the cavernous space, the stillness of the stale air, the peeling metal-rail balconies, the tattered drapes of dissolving fabric hanging above us like stage curtains, the clicks of my camera, the short grinds as I forwarded the black & white 35 millimeter film after each exposure.

Later, on our way out, we passed a sign screwed to the wall saying something like DANGER saying ASBESTOS saying CANCER saying GET OUT.

My girlfriend and I are renting a fishing boat to explore the nearby lake tomorrow, leaving our cat in sole possession of this cabin for the day. Hopefully the moose and bears will leave her be. After hopping online to check the reservation, I’ve navigated spotty wi-fi to see what Google has to show me about that old college building way down in Athens County. Turns out Street View photographed it back in October 2019, twenty-five years since my friend and I were there. Gordy Hall’s been renovated and expanded back towards where the derelict building began. And the pool itself? It’s now a sunken, open parking lot: a few silver hatchbacks, an SUV, one red pick-up. Off to the right, a squirrel on the sidewalk stares bemusedly up into a small tree. On the entrance to the parking lot, what looks like a blank piece of paper, bright white against the skid-marked pavement. At the time Google’s fish-eye lenses motored down University Terrace, the light was coming in angled from over the building across the street. Just the way it did when it filtered through those painted windows, haloing the naked body of my friend wobbling, barely balancing on the springy high jump board above an empty pool far below, his bare arms reaching into the air at either side, me somewhere down below, looking up, trying my best to capture the fleeting images.

Jon Riccio is the author of two chapbooks, Prodigal Cocktail Umbrella, and Eye, Romanov. He serves as the poetry editor at Fairy Tale Review and was a digital projects intern for the University of Arizona Poetry Center.