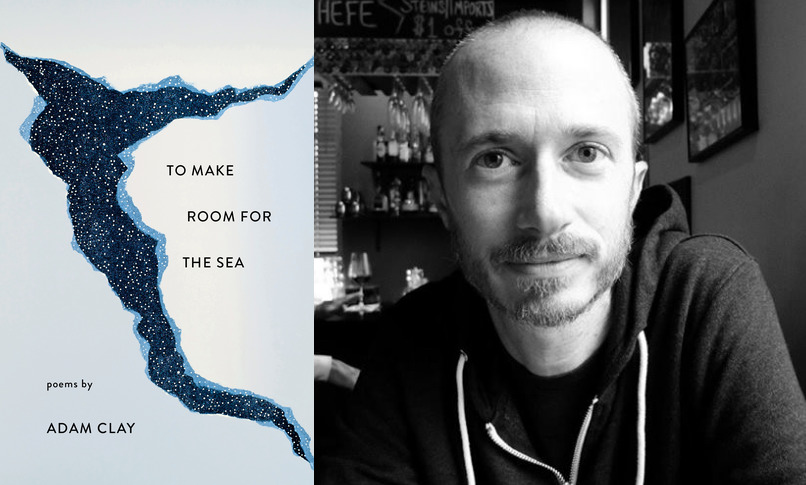

Adam Clay is the author of To Make Room for the Sea (Milkweed Editions, 2020), Stranger (Milkweed Editions, 2016), A Hotel Lobby at the Edge of the World (Milkweed Editions, 2012), and The Wash (Parlor Press, 2006). His poems have appeared in Ploughshares, Denver Quarterly, Tin House, Bennington Review, Georgia Review, Boston Review, jubilat, Iowa Review, The Pinch, and elsewhere. He is editor-in-chief of Mississippi Review, a co-editor of Typo Magazine, and a Book Review Editor for Kenyon Review. He directs the Center for Writers at the University of Southern Mississippi.

Jon Riccio: I’m glad we’re discussing To Make Room for the Sea, which interrogates hope, fatherhood, and the physics of time—“like how an instant felt less cosmic / and more like a coffee spoon wound around the mug” (“How Do You Feel about Ashbery?”)—among others. Interestingly, the first of these items “swims better than / it flies” (“Good-bye to Golden Nights”). You offer not one but two sestinas, in addition to a ghazal, sonnet, and abecedarian, these forms each a reflecting pool for such free-verse lines as

History

waits for everyone or for

no one, and a shawl covers

only what’s a thumb smaller

than itself. (“The Terror of Flight”)

“How the World Began” contains similar notions of history in which “The years of the locust tree / split open with ease.” This image harkens to the collection’s fissure-adorned cover, its rift resembling a waiting room for constellations. “I always liked missing you,” the poem tells us, “stirring the coals with only / the action of my mind.” What aspects of this book are antidotes to longing?

Adam Clay: Thank you for these kind words, Jon. I really appreciate the time you’ve taken with my poems. This question about longing is such an interesting place to start. If I was pressed to say, I’d offer that my poems explore notions of perception and perspective more than anything else. Longing and loss (in and of themselves) really only emerge based on where a person is personally and emotionally. My previous book, Stranger, thought about this idea through how becoming a parent can change even the most basic and simple things around us. To Make Room for the Sea is still thinking about perception and perspective, but I’d guess that the poems are less interested in walking around that idea and interrogating it. It’s become an idea I’m more comfortable with in my poems, and the book is engaging with the quotidian actions of a day with the ghost of that understanding behind it.

JR: I appreciated the contrasts in “At the Heart of a Multitude of Things,” where “There’s a fumbling sense / of hope, a tiny branch dropped in the ocean for / the long float toward land,” a David to the poem’s inquiry Goliaths, “What replaces the irreplaceable?” and “What should a life be for?” Adding to their complexity, these questions appear in a sestina whose end-words include arrive and vanishes. How does To Make Room for the Sea grapple with the ebb and flow of hope, which is often associated with water when it appears in-text?

AC: “Meditation for the Silence of Morning” was one of the first poems I wrote for this book, and I really thought the collection was going to be about climate change primarily. It’s an issue I think about on a daily basis, and it’s something I think a lot about as a father, too, in terms of what kind of a world I’ll be leaving behind for my daughter. And, to be honest, writing poems about climate change is not really a hopeful thing. I spent a lot of time thinking about what hope can even look like considering the world we’re living in, and I’m still not even sure I know the answer, to be honest. At times now even writing a poem during a pandemic feels like a pretty futile thing, but I’ve grown to see poetry as a form of meditation, and a central idea of meditation is acceptance. Grief, fear, and loneliness are all pretty terrible things, but they become more terrible if we don’t accept them, and I wanted a lot of my poems to simply dwell in their moments (no matter what those moments might be) and see what might emerge from those meditative experiences.

JR: Technology and religion intersect in “Blue Screen of Death,” the poem asking

What other animal

would teach a computer

to be a Buddhist, to design itself

right out of existence with this much

hubris?

Earlier, your friend Richie in “Now Warm and Capable” “[posits] that search engine histories / have become the closest thing // to prayer we have.” It’s only a matter of vigils until data’s awarded a patron saint, right? These excerpts remind me of transhumanism, a movement “that explores human transcendence above or beyond organic, corporeal limitations through technological and philosophical evolution[i].” While I can think of several fiction writers whose work features varying degrees of transhumanism—Iain M. Banks, Octavia Butler, Ted Chiang, Philip K. Dick, and Yuri Nikitin to name a few—I’m at a loss for poets who address these possibilities beyond Lo Kwa Mei-en’s The Bees Make Money in the Lion (2016) and Jillian Weise’s Cyborg Detective (2019). Are there others whose collections examine this genre? Do you think it’s easier to align transhumanism with fiction than poetry?

AC: Perhaps that’s the case; I guess plot (longform as a novel or as a short story) allows the imagination to consider what life with technology intersecting all facets actually can look like. There’s a Silver Jews verse that comes to mind here:

Robot walks into a bar

Orders a drink, lays down a bill

Bartender says, “Hey, we don't serve robots”

And the robot says, “Oh, but someday you will”

I’ve never thought at length about genre and tense/time, but I feel like my poems dwell more in the present or past, whereas I don’t think many of my poems have explored the future until now. And maybe that explains the difference: the lyrical quality of many poems is looking inward to the moment at hand, whereas a narrative-driven piece might be looking outward to a future that’s yet to exist.

JR: The “Only Child” sequence occurs in reverse order, from (III) to (I). As the poems lengthen, their lines shorten, (I) achieving columnar resemblance amid the declaration

I had always

imagined a different type

of fatherhood before

fatherhood found me,

Time factors into (III), which begins “In these months of rethinking, one wonders / where to find rest again. Where in a moment / is the music of a dying leaf?” I reread “Only Child” with W.D. Snodgrass’ “Heart’s Needle”—his reckoning of a father-daughter relationship—in mind. Time is a barrier in that poem, its ramifications palpable on Halloween when his daughter

[goes] with your bag from door to door

foraging for treats. How queer:

when you take off your mask

my neighbors must forget and ask

whose child you are.

Might “Only Child” stand as a counterclaim to Snodgrass’ scenarios where he braids the paternal and time? As a follow-up question, what poems resonate with your ideas on fatherhood?

AC: I like the way you think about time as a barrier in the Snodgrass poem. As I mentioned earlier, my book Stranger was really focused on how parenthood changes the world in both major and minor ways; I found my relation to time shifting greatly—with a new child, the luxury of taking a morning to work on a poem goes away, but it’s not something I found myself really missing. I just shifted priorities and found that my relationship to drafting poems (and, well, to everything) changed. Eventually when I figured out how to write about fatherhood in a way that didn’t feel too precious or sentimental, I discovered poems about fatherhood were a way to stop time. And perhaps all poems do this (or attempt to). Frost says they’re a “momentary stay against confusion,” but maybe they’re a “stay against time.” I go through periods, too, where I write a poem daily (sometimes for a few months at a time), and those poems become a record of those times in my life.

Poems about fatherhood that come to mind immediately are some of the obvious ones: Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays” and Roethke’s “My Papa’s Waltz,” but I’ve always loved Larry Levis’ “Winter Stars,” Natasha Trethewey’s “Myth,” and Weldon Kees’ “For my Daughter.” The latter is an outlier among this group, but I’ve always thought it’s a fascinating look at fatherhood from the perspective of someone who doesn’t have a child. Andrew Grace’s “Do You Consider Writing to be Therapeutic?”, which we published in Mississippi Review, is a poem about a father that I think about a lot, especially in its conclusion and what Grace accomplishes with time:

I should have talked

to someone before now

and not you. Poetry is not talking.

This is just art

and therefore could never

cover my ears when I, suddenly,

am back in the shed

and I learn again that my father

has died every day

since he died.

JR: When questioned about happiness, “Taken Off the Bone” responds that it’s “Some strange sort of forever / or whatever—like the time number you’d / call to set your clock to,” as if we wouldn’t know happiness unless an automated voice spelled it out for us (ah, transhumanism). Toward which direction is To Make Room for the Sea more inclined: contentment or bearing “a path to loneliness” (“Where the Map Is”)?

AC: What a great question. Can I say that I don’t necessarily see the two paths as being mutually exclusive? “Taken Off the Bone” (which is actually a “golden shovel” based on Mary Ruefle’s “Trances of the Blast”) and a number of the other poems around it were written at a time when I was trying to settle into a notion or understanding of loneliness as an acceptable state of being. I remember the poet Marcus Jackson talking to high school students at Kenyon College one summer and telling them that loneliness was a path to the weird. That idea stuck with me in a lot of ways. I always thought of loneliness as a bad thing, as a negative state of being, but I think these poems are trying to reckon with perspective and shift that view, somehow. What if we dive headlong into moments of loneliness and see what might come from them? What might we learn about ourselves through those experiences? I’m not sure the poems answer those questions, but they were certainly in my mind as I wrote them.

JR: Though “The Art That We Are” spends the majority of its lines pondering “an afterlife / void of feelings,” it concludes on a reconfigured option—

An experience without feeling

or a feeling without experience?

I choose neither. I fashion each

fleeting thought into a tiny lead boat.

I admire the transport’s size and elemental makeup, not to mention the poem ending on a one-syllable long-O sound. This passage shows an “I” versed in solutions, a lyric MacGyver. A bit later, the “I” in “What Shines Does Not Always Need To” substitutes knowledge for amazement “at the weight an ant could carry. I used to be surprised / by survival. But now I know the mind can carry / itself to the infinite power.” I think there’s a tug-of-war in contemporary poetry between poems that hit their stride through ingenuity versus those whose pathos astonishes. Care to weigh in on this?

AC: I can definitely see how these two things might be pulling against each other. I guess I prefer to avoid generalizing too much about poetry because every poem is unique in what it sets out to accomplish (and in how it accomplishes it). I might prefer to think about these concepts in broader terms like “music” and “meaning” and how one might direct a poet’s impulse from the start. A poem that starts with music is going to be radically different than a poem that starts with meaning (or an idea). I don’t think they’re necessarily opposing forces, though, as music often leads to meaning and meaning often leads to music. I rarely sit down and write from a place of pathos or emotion—my poems tend to come from music and work their way towards an idea or meaning.

JR: It took me until “xerothermic” to realize “The Seams Don’t Show” is an abecedarian, a testament to its level of craftsmanship. The poem’s impact has little to do with diction gymnastics, as its weight resides in observations—“Just now I find myself caught in the folds of a sentence / kindness forgot” and “we usually stop finding the universe / new by afternoon” are two such exemplars. Were earlier drafts of the poem as straightforward? Which poets help you remember kindness?

AC: I do feel like the poem’s early drafts were similar to where it ended up. Some compression happened during revision because the poem’s lines were longer (and it didn’t quite fit on the page). I ended up having to cut and trim during the final stages of production. Mary Austin Speaker, who designed the book, is an amazing poet and had some wonderful suggestions for making the poem work visually and linguistically.

In terms of kindness, I go to Ross Gay’s poems a lot for a deeper understanding of what it means to be kind. His poems aren’t only interested in kindness as a human venture; they explore kindness in relation to how we interact with nature, something that seems more and more important to think and write about. His poem “To the Fig Tree on 9th and Christian” feels like the perfect blend of both.

JR: I love how you describe a window as “a rectangle to see / the fragments / of the world through” (“In Bed and Where Is the Sun?”) because it changes my understanding of what windows are capable of, and how I may write about them moving forward. I had the same experience with wallpaper when I entered Mary Ruefle’s “Crone” into the layout of Mississippi Review 46.3, her lines “Some wallpaper is forested, / some citified with buildings, / but I’ve never seen any with graveyards.” still powerful two years on. Who can even write about a light switch after that? Your reverence for time and the abovementioned artist culminate in “Immortality for Mary Ruefle,” its prose essaying foreverness. Here, restoration vies with concealment, and we revisit the collection’s steadfast companion, water. How has being an ardent reader of Mary Ruefle shaped your work?

AC: There’s something I really admire about her work—her poems have always had a spell-like quality for me. I’m drawn to them, too, because her poems feel so unlike anything I’m capable of writing. The writers I admire the most are the ones that pull things off I feel uncapable of doing in my own work. If I had to put my finger on a single thing I love about her work, it would be the way she makes the mundane magical; I really feel like I’m inside her head when I’m reading her poems and seeing the world through her unique perspective.

JR: You’re entering your fourth year as Editor-in-Chief at Mississippi Review. It was an honor serving as one of its associate editors between 2017 and 2019, during which time there was a growth of contributor diversity that continues to this day, Tiana Clark, Jennifer Givhan, Elisa Gonzalez, Marcus Jackson, Neshat Khan, and Tomás Q. Morín among those published in 2019-20. What groundwork are you laying to further engage writers of color, disabled writers, and members of the LGBTQ community?

AC: It was a joy working with you on MR, Jon; you taught me a lot about literary citizenship through the writers you brought to the table and your work on social media highlighting writers. Diversity is something I’m thinking about a lot from an editorial perspective; because one of our issues each year is solicited, I feel there’s a responsibility to reach out to a diverse group of writers in putting those issues together. I’m currently working on my fourth solicited issue, and I’m learning quickly that it’s important to reach out to friends and colleagues to inquire about writers to solicit as well. It’s a challenge to keep up on everything happening in the publishing world, and depending on others to help with solicitating work is important. I hope to bring in guest editors, too, and think about projects that might highlight and illuminate the voices that need to be heard.

JR: I enjoyed our discussion, Adam. It feels like I never left the Center for Writers, of which you were named director last February. What would you say to those who find themselves in the linked roles of artist/educator/administrator, with regards to leading structural change, whether it’s proposing a new course or remapping their department’s comprehensive-exam reading lists?

AC: I depend a lot on my colleagues and their expertise. My predecessor as director, Angela Ball, is an invaluable resource, too. One of the advantages of being in the position I’m in now is that the Center for Writers already had an aesthetic or “vibe” in place so there wasn’t a need to think about who we are as a program; rather, we can think about how our structural changes might connect to this tradition and history of being a program that values “serious play.” It’s odd to step into this role ahead of a pandemic but seeing the adaptations we’ve had to make as strengths rather than as a problem has been another key thing that’s driven our discussions. I never imagined myself in an administrative role, but I feel really lucky to be where I am, editing Mississippi Review and working with students like yourself that consistently expand my notions of what poetry can do or be.

Jon Riccio’s Eye, Romanov and Agoreography are forthcoming from SurVision Books and 3: A Taos Press. He was a past digital projects intern at the University of Arizona Poetry Center.

[i] https://www.dictionary.com/browse/transhumanism?s=t