“Inside of the sea, there is more than the sea,” I read, and the twenty or so first-graders in front of me moved their arms and torsos in undulating, wave-like motions. I was orating a stanza from Aracelis Girmay’s poem “luam, who says to the dead // --sea near lampedusa” (The Black Maria, BOA Editions 2015), and urging the students to act it out with their arms, legs, and facial expressions. At “rockets,” they jumped into the air, pantomiming fireworks, at “amphora” they stood still with rounded arms, pretending to be hollow and earthen. They loved performing “icarus”--they flapped their wings and then, hitting an imaginary Sun, crumpled to the floor (as children sometimes do, one student copied another until the class was performing synchronized motions). They snapped “photographs” and did jazz hands at ear level for the line “gold earrings.” And at “luam” some swayed their arms gently and others pretended to sleep, suggesting restfulness, peace.

The exercise was designed as a way to get excess energy out and put some of the brand-new words the first-graders had just learned into motion. Words like “inside,” “sea,” and “more” were familiar to the students, but farther down in the stanza a new lexicon appeared--“amphora,” “debris,” “icarus,” “luam.” We had defined the words together, talking about clay jars, Greek myths and “luam,” a name that means “peaceful or restful” in the Tigrinya language spoken in Eritrea, where Girmay’s father is from. I showed them Eritrea on a map, and asked who sat at the table labeled “Africa,” trying to make the wide world of the poem relevant to the smaller, but scarcely less complicated, world of the classroom. Then they got up, spread out far enough apart from one another that they would have space to jump and gesture wildly, and enthusiastically danced the poem.

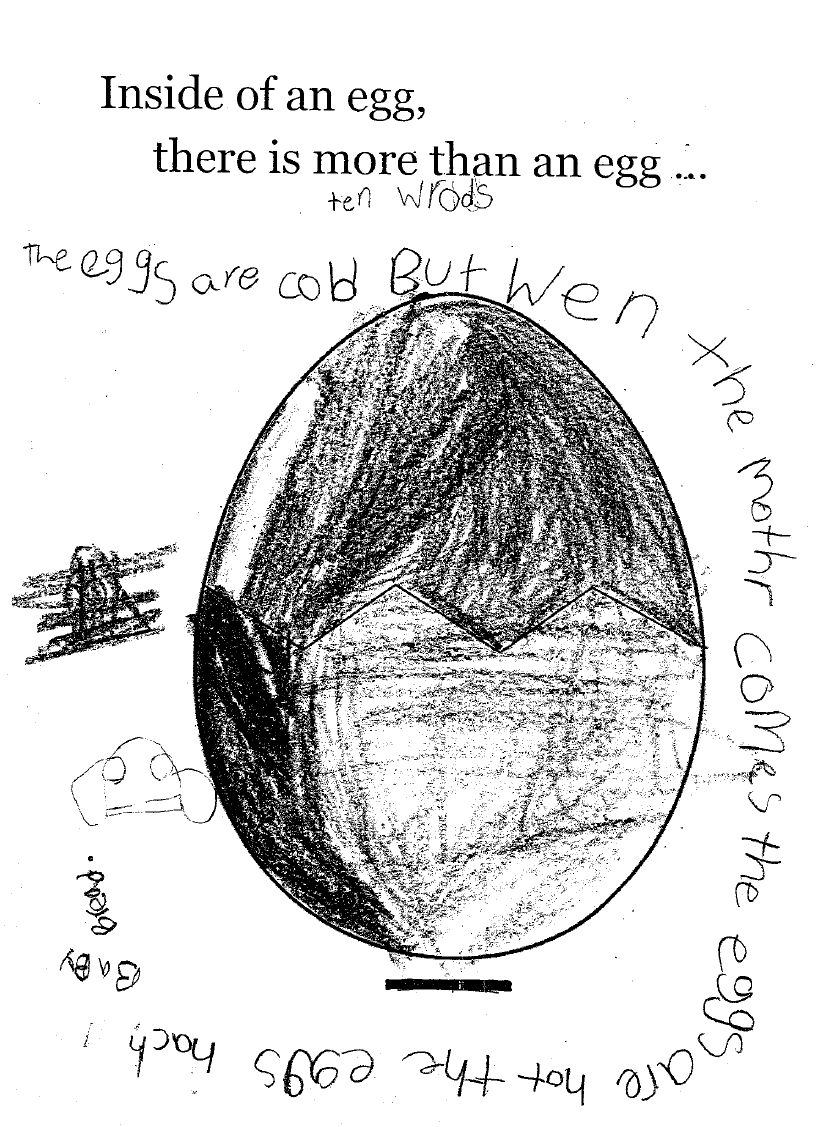

I’m not a dancer (I have, as the old cliché says, two left feet) and so, as I was planning the lesson, I didn’t spend much time on the movement portion of it. I was instead focused on the individual poems the students would write afterwards, which began with the line “Inside of an egg, there is more than an egg” (they are building a chicken coop this semester, so much of the poetry we read and write deals with those funny, flightless birds). And yes, the students made clever, creative poems--one student, Julienne Almasi, wrote in pencil letters circling the egg template I had given them, “The eggs are cold but when the mother comes the eggs are hot the eggs hatch, baby bread; another student, Luciana Reyes, had decided that their rainbow-colored egg was full of “ghosts,” “rocks,” “monsters,” “burgers,” and a “fox.” But after the lesson, it was the movement exercise that stuck with me, and it struck me that perhaps it was the most effective thing I had done all day in terms of my primary goal for the class: to inspire the students to see poetry as something compelling, enjoyable, and attainable; something they can read and respond to and write.

This stanza, like so much of The Black Maria, is about migration. While we didn’t talk about that theme directly, the small migration that it made within the classroom--from the printed page to the strongly-felt movements of the first-graders--seemed a fitting way to honor and to come to know Girmay’s powerful stanza. By pausing on each word and letting the students embody it I was, I hope, also letting another lesson sink in: the idea that nothing is ever what it looks to be on the surface; that the world is more complicated and painful and beautiful than it seems; that to get beneath the veneer of it all we must pause, listen, and let the words sink into the marrow of our bones.

Wren Awry is a writer and current Writing the Community student.