People fear poetry because they don’t “understand” it.

Once at a teaching conference, I met a woman who was about to teach an introductory poetry class. She confided that she’d never taught poetry before. I asked her what poets she’d decided to teach. She said airily, “Oh, actually, I’m teaching all films, and we’ll look at the poetic influences on imagery.” I stared at her with my mouth open and thought, She’s afraid of poetry.

People fear poetry because they don’t “understand” it. This is what they say. But I suspect people fear poetry because it shakes the tree of the known, uses language and uncanny forms to facet and reflect the unsaid in human lives, makes the seemingly knowable unknown. In this way, poetry brings the culture forward, changes the world.

This is terrifying if you like the status quo. This is exhilarating if you accept that change is the essence of life. I trust poets to startle-shape the path for us to move forward from what we’ve gotten wrong. (At the end of this blog, I offer a method for finding your way into difficult poems.)

Since April is a month dedicated to poetry,

I suggest you examine your own relationship to poetry.

* * *

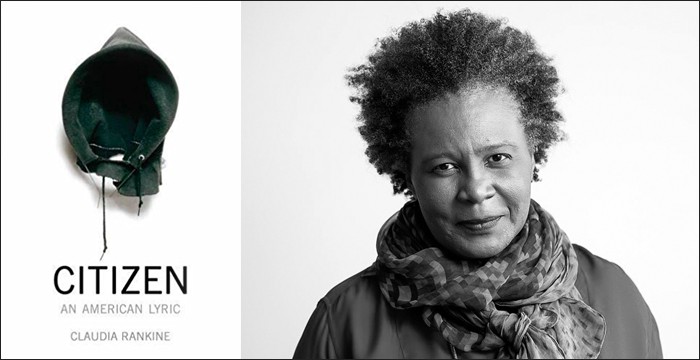

In Claudia Rankine’s book-length poem, Citizen: An American Lyric, she gathers poetic evidence to illustrate the breadth of America’s racism: narration of aggressions and microaggressions, photographs, quotations, metaphors. It takes the gathered form of this book to illustrate the daily, careless, overtly accepted nature of such harm. Rankine needs a variety of tools to breathe this truth into the reader.

The rain this morning pours from the gutters and everywhere else it is lost in the trees. You need your glasses to single out what you know is there because doubt is inexorable; you put on your glasses. The trees, their bark, their leaves, even the dead ones, are more vibrant wet. Yes, and it’s raining. Each moment is like this - before it can be known, categorized as similar to another thing and dismissed, it has to be experienced, it has to be seen. What did he just say? Did she really just say that? Did I hear what I think I heard? Did that just come out of my mouth, his mouth, your mouth? The moment stinks. Still you want to stop looking at the trees. You want to walk out and stand among them. And as light as the rain seems, it still rains down on you.

To understand racism as a concept is a different experience than to have the language and structural choices of a poet lay it down inside you, to saturate you so that you, too, must acknowledge the monstrous hatred that teems in this land, and since “it still rains down” on us all, we all must consider our part.

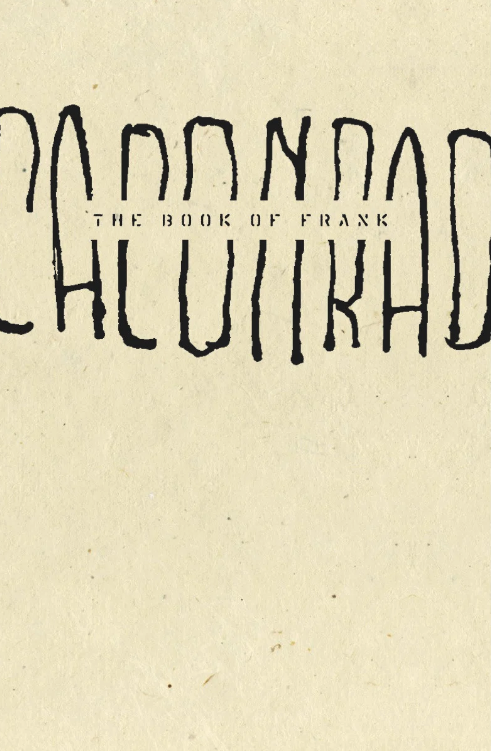

In CA Conrad’s Book of Frank, Conrad uses surrealist portraits to illustrate the realism of familial failure, the devastations of abuse. A coming-of-age book, Frank is by turns innocent and ribald and accusatory and bewildered. The characters do and say disgusting, tender, violent, sincere things, both exaggerated and on point, exactly like people do. To this nonbinary truth of a reality so many want to make binary, Conrad offers juxtapositions of danger and joy, of being alive and willfully dead.

‘This is your captain’ Frank says from the cockpit

‘all passengers wishing to bail out

Any time during our flight

it

is

too

late

I have shredded the parachutes to confetti

In celebration of our arrival’

Using white space and line breaks, they warn us: “it/is/too/late” to bail (true of all of us alive in this moment). But also, what can save us might have to save us in other ways, suggesting that reframing, re-viewing can offer up the new paths we need to change what is dead inside of our lives. Will parachutes save us? Or maybe something more nuanced, such as remembering to celebrate.

‘there’s a small bird I want to save’ Frank says

‘give it a chance

but it’s the size

of my heart

and I know

futility when

I see it’

Reframing, re-seeing, is hard work, full of doubt, but I always respond to Frank’s initial impulse: to save, to offer chances.

we can trust poets to use their tools

of form, symbol, white space, poetic line,

metaphor, experience and attention

What is untrustworthy, the poet Anne Waldman notes, is our bland acceptance of what is no good for us, our eyes closing against the pain of others. From “Revolution,”

Spooky summer on the horizon I’m gazing at

from my window into the streets

That’s where it’s going to be where everyone is

walking around, looking around out in the open

suspecting each other’s heart to open fire

all over the streets

Waldman provides abstractions to illustrate the betrayals of our culture. When performing her work, she shakes us out of our stupor, her hands squeezing the air, her raised voice pointing to the ticking clock of passively accepted doom. Embodying ritual structures of “body, speech, and mind,” she names the ways that America culture buries cruelties, supports aggressions, ignores the planet, and she offers those ways back to us in an altered state for clarity. In “Anthropocene Blues” she warns,

nothing

not

held hostage

by the hand

of Man

can we resist?

will we fail?

to save our world?

we dream replicas of ourselves

fragile, broken

robotic thought-bubbles

inside the shadow

a looming possibility

this new year

to wake up

could it be?

We can say these things prosaically, that racism = death, child abuse = death, hiding from our inhumane and climactic mistakes = death. Or we can trust poets to use their tools of form, symbol, white space, poetic line, metaphor, experience and attention, to risk rousing the citizens who must wake or die, to risk giving ourselves another chance.

* * *

Since April is a month dedicated to poetry, I suggest you examine your own relationship to poetry. What do you love about it? What intimidates you about it? Which poets speak to you immediately? Which ones mystify you? When I was teaching poetry in foundation English classes to hosts of students convinced that poetry “wasn’t for them,” I created a method for reading based on the ideas behind the Benedictine Monk's Lectio Davino (divine reading), a devotional, repetitive practice of reading.

I suggest you find a poem that mystifies or troubles or eludes you

and read it four times aloud, using these guidelines.

Step One: Read Lightly.

Allow images, ideas, sentences, phrases, single words to catch your attention. Let there be free association. Make note of any of words or ideas that interest you. Look up any words you don’t know. Think about why you like a certain word or phrase. Think about any sounds patterns you find. You might simply love a word for no obvious reason. This is fine! This is great! Let this happen.

Step Two: Read for Action.

Write down what you think is taking place in the text, whether this means actual action (two men are fighting over money), or simply thoughts or ideas or memories on the part of the author (a cloud represents freedom to a prisoner). Is there any kind of a mood? Even understanding one single section or one single line can be a pleasure.

Step Three: Read for Connection.

Can you connect with this speaker’s ideas in any ways? Do you feel anything at all about this text? Do you feel sympathetic or scornful or interested towards any action, images, or ideas in the text? Is the speaker saying something you believe in or something you disagree with? Do you find anything beautiful in the way it looks on the page or sounds? Does it speak to your own heart or knowledge?

Step Four: Read for Contemplation.

Does the speaker give you an image of something you didn’t have before? Did they say something that surprised you? What feeling does it give you? What do you think is the main heart of the text? Do you have value assumptions that block your understanding? What does the poem say to you? Does this text reflect on the way you want to, or don’t want to, live your life, either personally or in community?

No poem is written for everyone. Of course not! If you don’t like some of the famous poets you were forced to learn in school, that is perfectly okay. You don’t have to love every poem. But make no mistake, there are poems written for you. Maybe this month you can go to the Poetry Center (free!) and sit in a comfy chair and read until you find one.

______

Frankie Rollins is the author of Do You Feel Like Writing? A Creative Guide To Artistic Confidence, and two books of fiction, The Grief Manuscript and The Sin Eater & Other Stories. She was shortlisted for Aesthetica’s Creative Writing Award 2023. Frankie is the founder of the Fifth Brain Collective, a platform offering online classes and coaching and community for creative people.