How wonderful it is to watch someone draw! From life or en plein air, the way the gaze shifts between paper and subject could seem a drama about our attempts to place our lives in good relation to the world. When someone is drawing images of their imagination, whether doodles or intricate geometries, an observer can watch, emanating from the artist, the force of creativity as the ideas resolve themselves. No matter what one draws or how beautiful the drawing is, the artist outlines the phenomenon of attention and becomes a mystery themself. And perhaps the payback for not being good at drawing is the added appreciation one has at seeing it done well—meaning, by someone who gets lost in the act.

I live in a household with two great artists of drawing, my wife Lynn and our six-year-old daughter. Drawings are all over our apartment and there’s a good chance, at any time of day, that someone is drawing. In fact, before writing this I was waiting to use the computer while my daughter was taking part in an online animal-drawing class. Today’s subject was the narwhal. If nobody is drawing, then most certainly there’s someone reading or writing (probably poetry). This ubiquity of drawing and poetry in our home was the primary inspiration for the show I’ve curated at the Poetry Center, On the Other Hand: Poets and the Practice of Drawing.

The show also emerged from an interest in another practice and its relationship to poetry. Some years ago, the Poetry Center hosted an exhibition of photographs from a poetry/photography book of mine called Castles and Islands, and a couple of years later I curated an exhibition of work by photographic artists who are also poets, at Woodland Pattern (a book center, gallery, and performance space in Milwaukee). That exhibition was called To Sight’s Limit, and the Poetry Center kindly offered to host a subsequent version of it in Tucson. Then the pandemic happened and everything was put on hold. When the thought of exhibitions became possible again, in October of last year, Julie at the Poetry Center contacted me about scheduling the show. At that time, drawing must have been especially intense in our home, and I asked if we might shift the focus from photography to poets’ drawings. Julie liked the idea and the rest came together quickly.

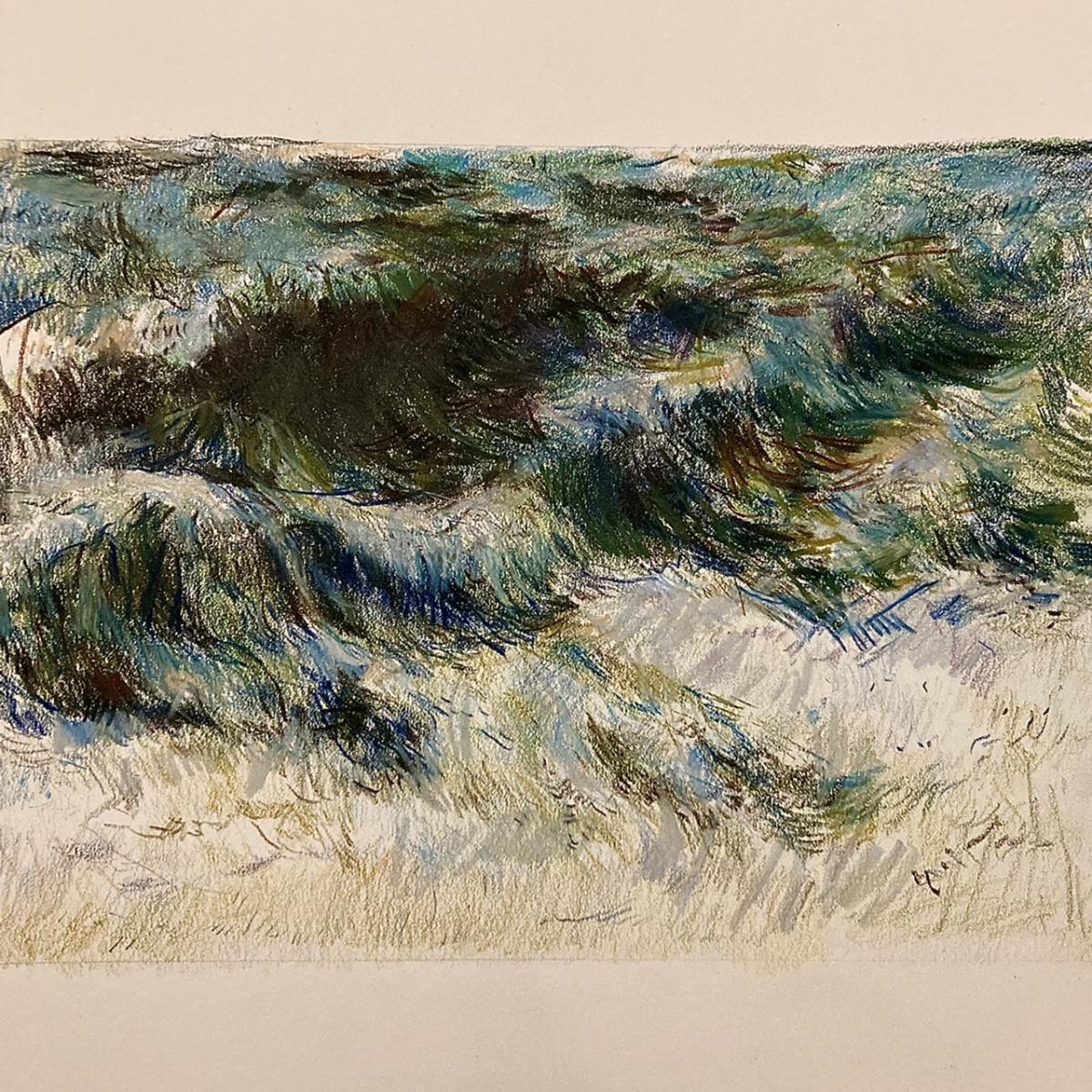

The first poet-artist was an easy pick since we live together and she’s my favorite poet: Lynn Xu. Lynn had been talking about making a series of drawings based on the seascapes Courbet painted not long before and during his involvement in the Paris Commune. The political and social implications of Courbet’s work is a matter for art history, but I was very interested in how Lynn’s thinking through our current moment was done in part through looking at and sketching in homage to the dead French realist, and how this was related to her writing. For the next poet-artist, I literally crossed the alleyway behind our house in Marfa, to where our neighbor, the poet, translator, bookseller, and gardener Tim Johnson was working on his garden. Like those of John Ruskin, Tim’s exquisite drawings are obscured by his many other talents, but fortunately they did not elude my prying eyes, and he was game to join in the show. I knew that he had in his possession some excellent large-scale drawings by a writer-artist I greatly admire, Renee Gladman, and she soon joined the group. At this time I’d also recruited the other four poet-artists. All are friends whose work I think of often: Sommer Browning, Kit Schluter, Brandon Shimoda, and giovanni singleton.

The display space and a desire to showcase a range of aesthetics gave me some parameters to work with, in terms of size and number of drawings, but when it came to selecting works, I left most of that in the hands of the artists. There were several conversations about different types of drawings, since several folks work in multiple modes, but for the most part the artists’ individual visions were already clear. Despite the distinctiveness of each person’s work, the diverse subjects, styles, and methods seem to work beautifully in conversation with each other: Tim Johnson’s subtle and sly graphite lines and the furious colored-pencil marks of Lynn Xu’s waves invoke different echoes of the same revolution; Brandon Shimoda speaks through contoured cityscapes to giovanni singleton, architect of bright geometries; Kit Schluter’s masked László Krasznahorkai seems to be well-acquainted with Sommer Browning’s hilarious word-comics (and indeed the portrait of the Hungarian novelist traveled in a little tube with those comics from Mexico, where both artists made the marks); and Renee Gladman’s fascinating and fascinated writing that cannot be read look on ready, as if reading, from nearby walls.

In my imagination there are many other versions of this exhibition. One features drawings by seven other superb contemporary poet-artists: one possible group is Alice Notley, Christopher Stackhouse, Mathias Svalina, Aram Saroyan, Jessy Randall, Bianca Stone, and Zachary Schomburg. Another imagined exhibition reaches back to include work by poets from earlier generations: Elizabeth Bishop’s crayon and graphite Tea Service, several of Etel Adnan’s artist books, works from Kenneth Patchen’s Aflame and Afun of Walking Faces: Fables and Drawings, several of Henri Michaux’s People on paysage works, portraits of friends by Mina Loy and Mayakovsky, and a handful of Federico García Lorca’s exquisite illustrations for his own poems. Yet another possibility, which I know very little about but find fascinating, would focus on how ink drawing, calligraphy, and poetry come together in the “literati paintings” (wenrenhua) of poets like Su Shi and Dong Qichang.

Also exciting to imagine are all the people everywhere making drawings and writing poems, and finding those places where the forms meet: the sketch artist doing her best to translate Verlaine after a long day of witness descriptions, the songwriter discovering that her pen has made a little house around two rhyming lines, the taggers who alternate words in a collaborative rendition of William Blake’s “The Garden of Love.” Hopefully On the Other Hand: Poets and the Practice of Drawing creates some new space for viewers to think of drawing and writing poems, that they may take time to join in these arts.

Joshua Edwards was born on Galveston Island and lives with his family in New York City and West Texas. He's the author of The Double Lamp of Solitude, Architecture for Travelers, The Exhausted Dream, Castles and Islands, Imperial Nostalgias, and Campeche (with photographs by his father, Van Edwards); and he translated María Baranda's Ficticia and co-translated Lao Yang’s Pee Poems. He directs Canarium Books, and teaches at Columbia University and Pratt Institute. www.architecturefortravelers.org