You may know that the University of Arizona Poetry Center’s founder was named Ruth Stephan. But how much do you know about Ruth Stephan’s legacy as a poet, novelist, filmmaker, and editor? Here are highlights from her productive and varied career.

The Poetry Center’s worn but treasured copy of Ruth Stephan’s first book of poetry can be found in our rare book room. At some point in the distant past, the book was taped along the edges of each fragile cover. Unfortunately the acidic tape caused some discoloration. Prelude to Poetry was published in 1946 by Editorial Lumen in Lima, Perú.

The Flight (Alfred A. Knopf, 1956) is one of two of Stephan’s historical novels about Queen Christina of Sweden. The second, My Crown, My Love, was published by Knopf in 1960. Queen Christina (1626-1689) fascinated Stephan as a powerful ruler whose life, filled with dramatic choices, did not conform to the gender norms of her society.

You might have already guessed that Ruth Stephan traveled widely, and this is true. During her travels in Perú, she became interested in collaborating with novelist, poet, and anthropologist José María Arguedas on what would be recognized as the first anthology of Quechua songs and stories in English translation. The Singing Mountaineers was published by the University of Texas Press in 1957.

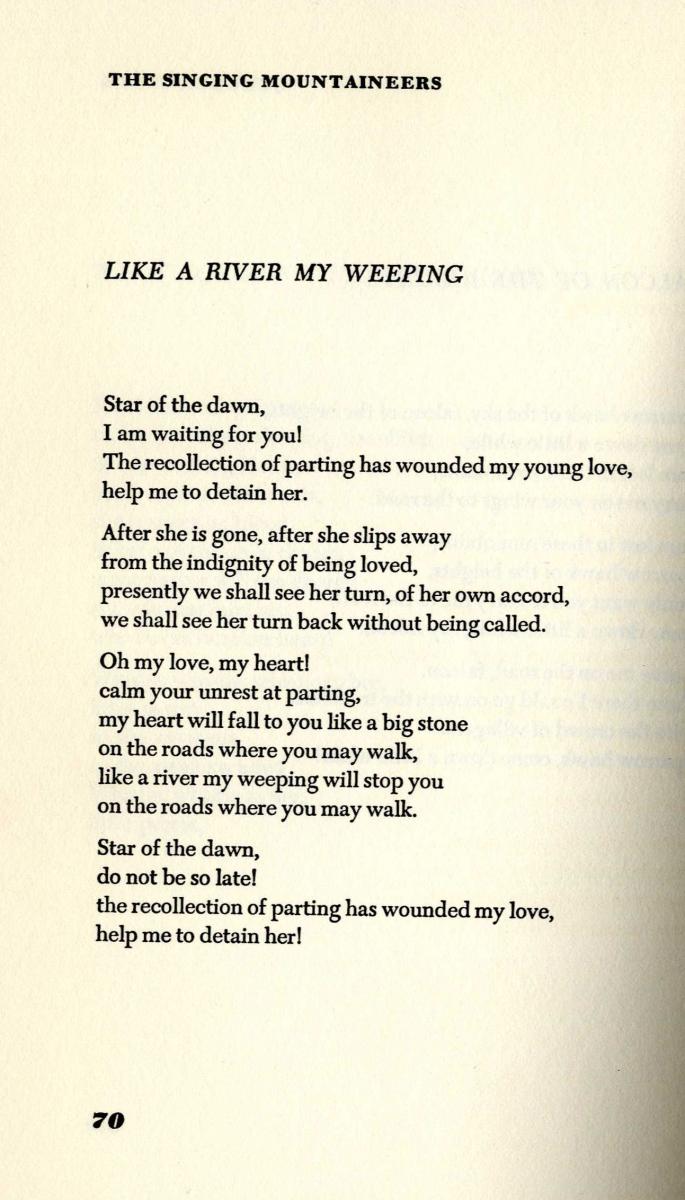

Here is one of the Quechua songs from The Singing Mountaineers, as translated into English by Ruth Stephan from José María Arguedas’s version in Spanish.

When Ruth Stephan founded the Poetry Center in 1960, she provided written notes on the purpose and maintenance of the Center’s library collection. These notes have served us well throughout the decades. Stephan’s writing is poetic, describing visitors to the library as those who “may respond freely, imagining or discarding meanings, or catching them like butterflies.”

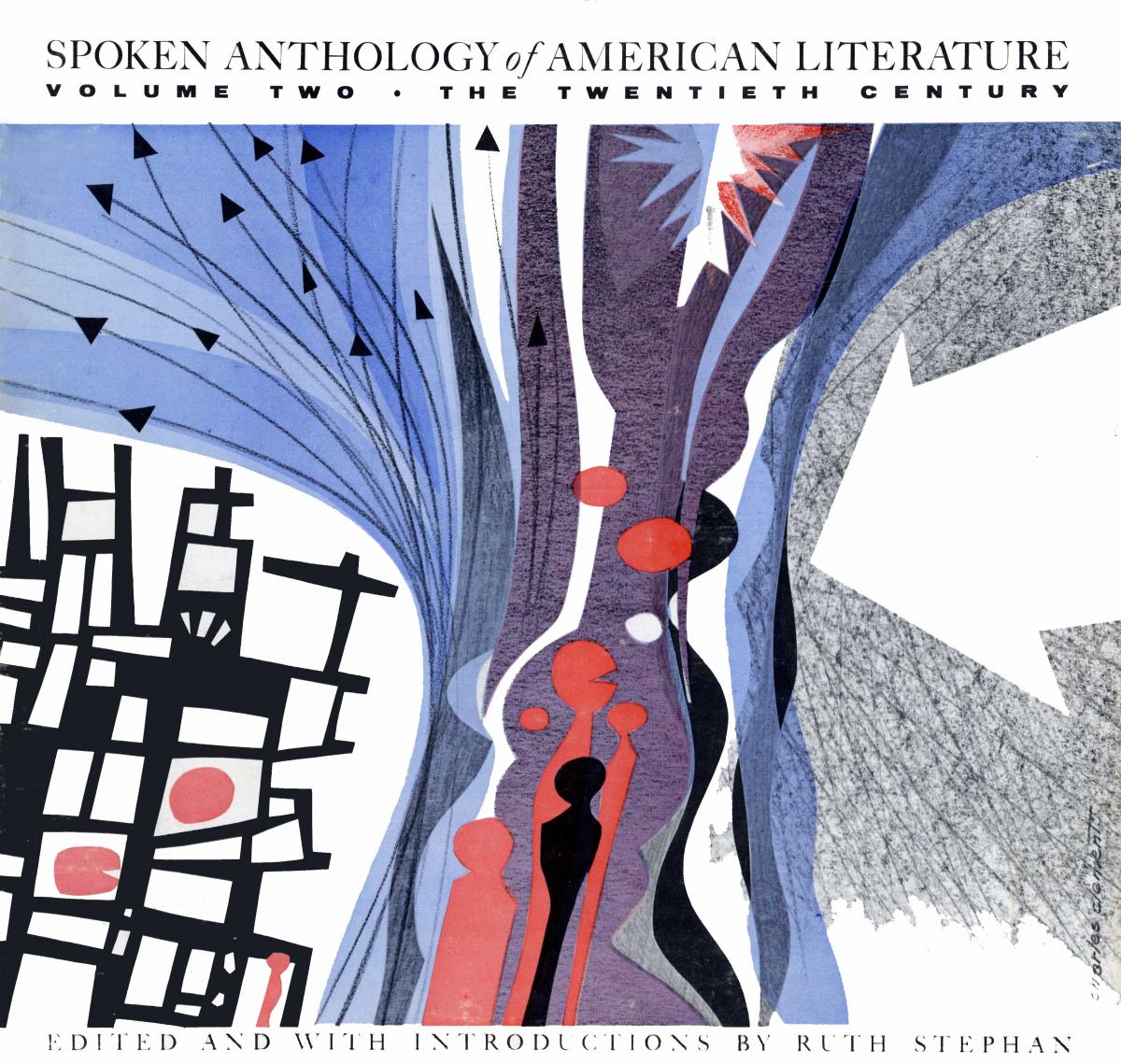

From 1961 to 1965, Stephan and Richard Shelton edited two anthologies of U.S. literature of the 19th and 20th centuries. Unusually, they were spoken anthologies with an emphasis on poems and fiction read aloud. The University of Arizona produced the record sets.

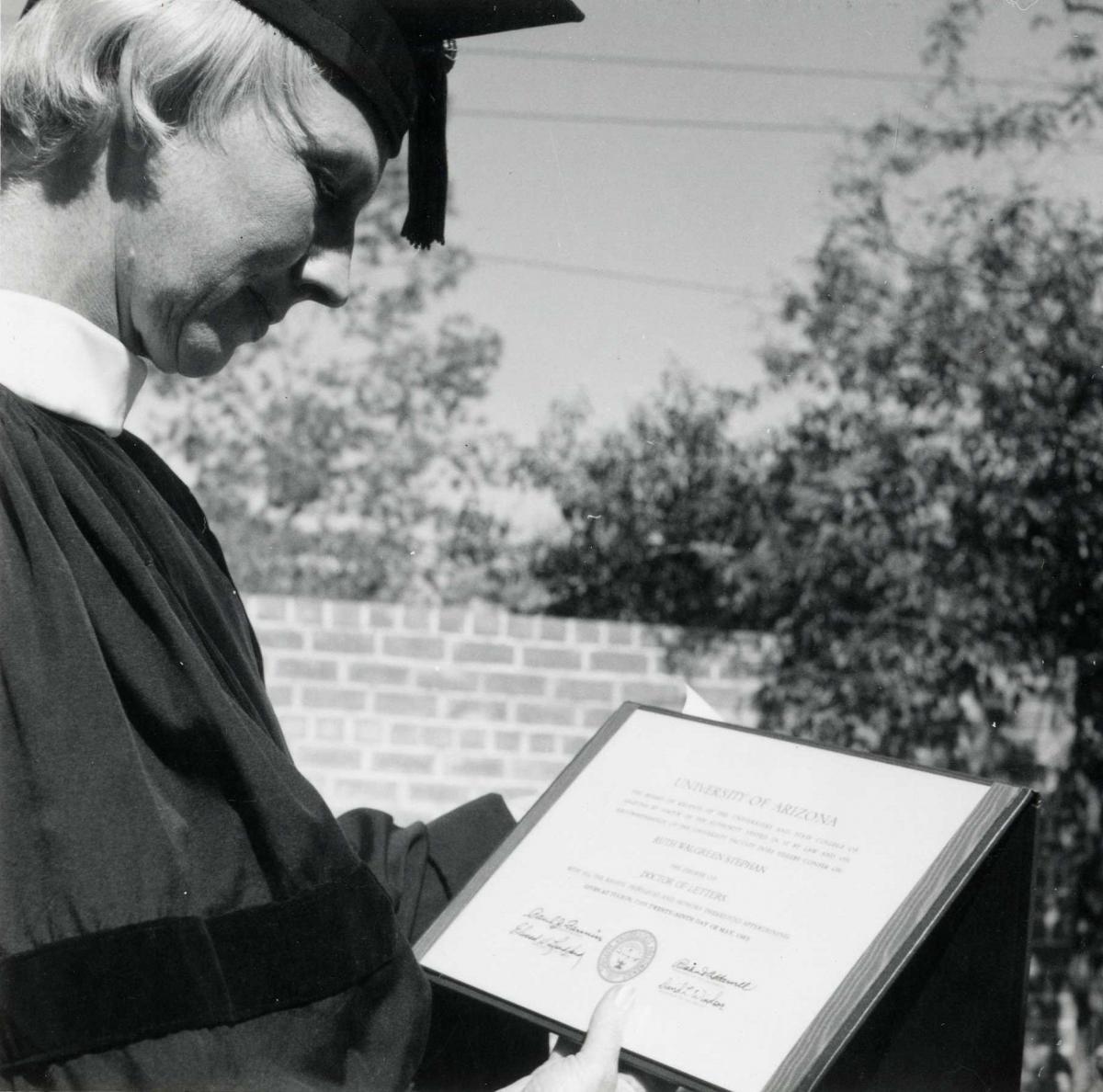

Stephan’s second book of poetry, Various Poems, published by Gotham Book Mart in 1963, coincided with another exciting distinction: she received an Honorary Doctorate of Letters from the University of Arizona in May of the same year.

Various Poems is influenced by Ruth Stephan’s travels in Japan. Stephan first visited Japan in July 1961 at the urging of author Percival Densmore (P. D.) Perkins. She was greeted at Itami Airport by one of her three sons, John J. Stephan. Another of Stephan's children, Justin Dart, Jr., lived in Japan in the 1960s. (Do you recognize Justin Dart’s name? He is well known as one of the primary advocates who helped to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act.)

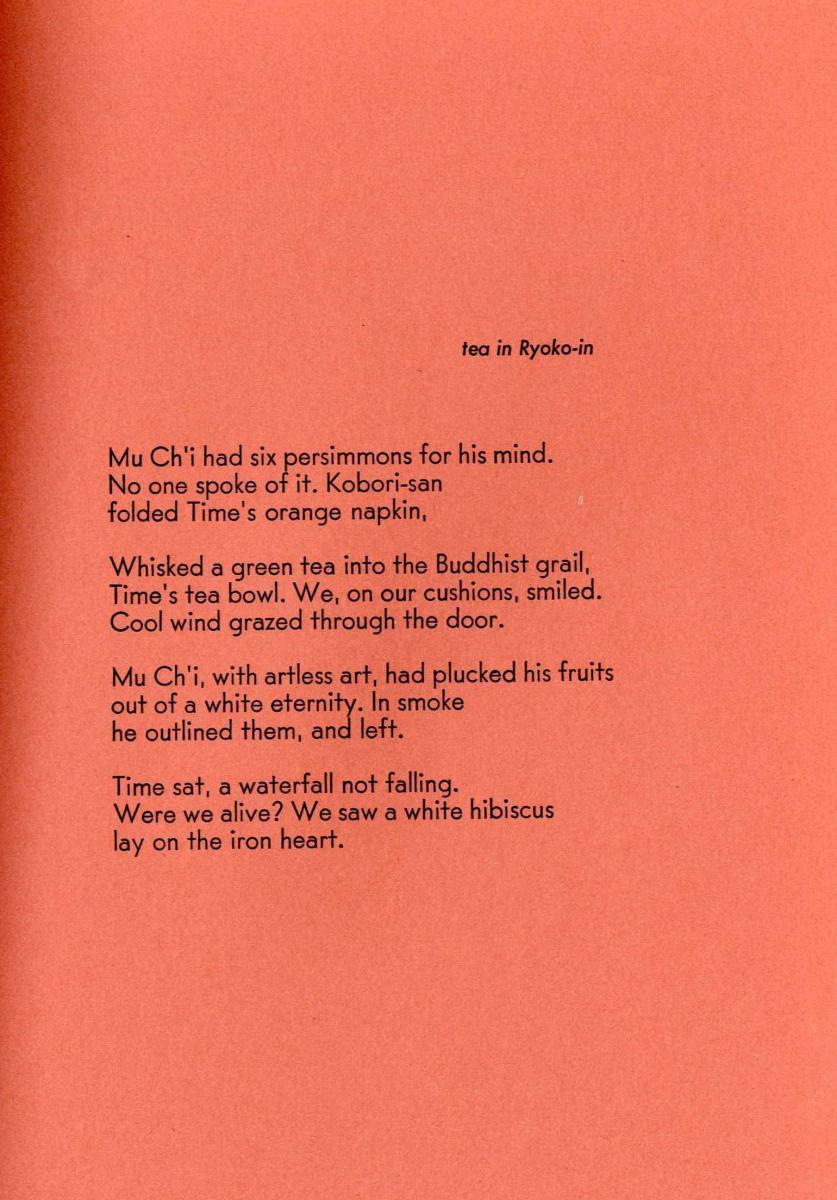

“Tea in Ryoko-in,” from Various Poems, reflects Stephan’s devotion to the Daitokuji monastery in Kyoto, which includes the temple of Ryoko-in. On voca, you can listen to Stephan’s friend, legendary poet Gary Snyder, discuss the significance of the painting by Mu Ch’i described in the poem.

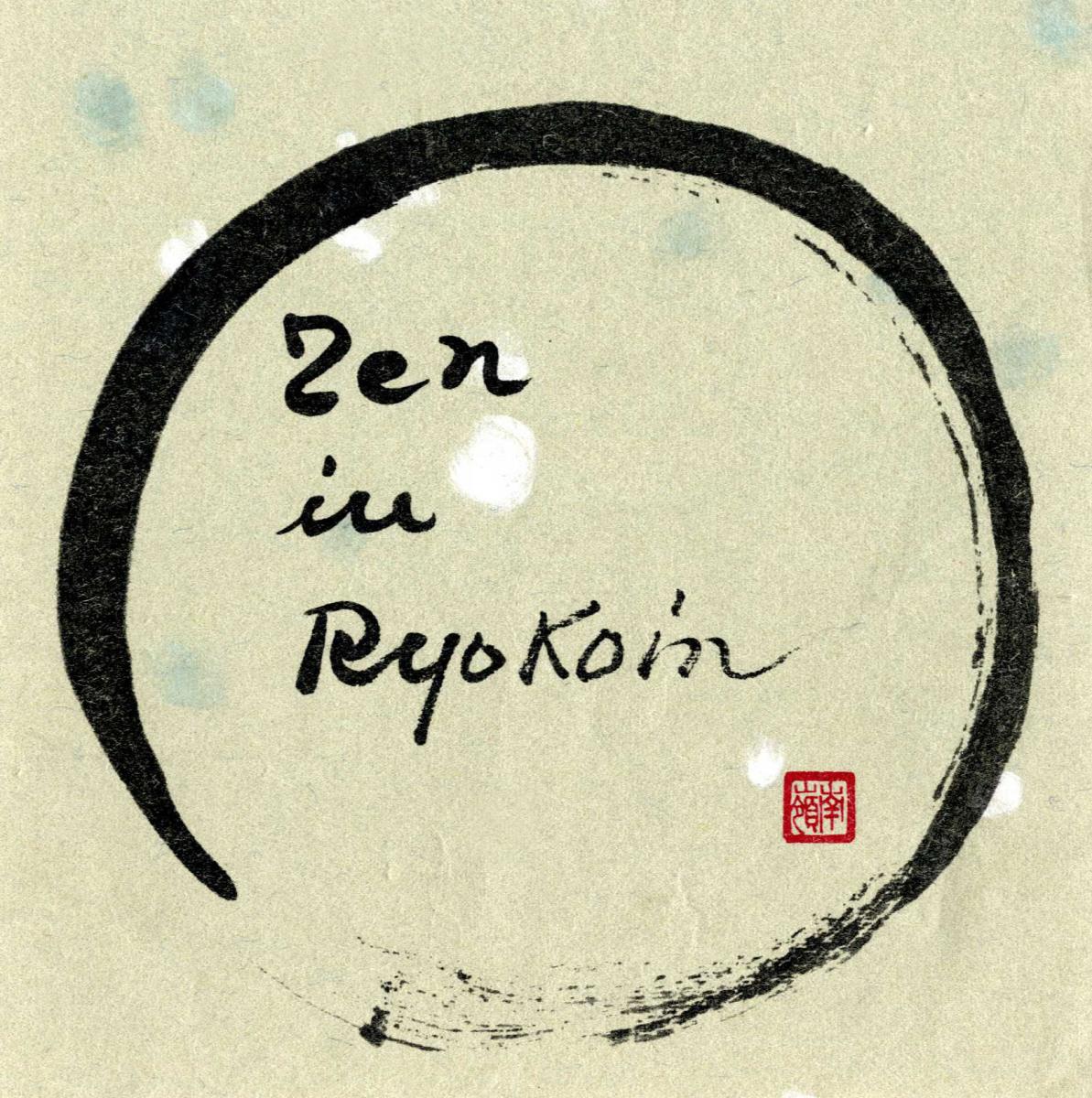

In 1972, Ruth Stephan produced and narrated a documentary film about daily life at Ryoko-in. Zen in Ryoko-in has been digitized by the Poetry Center from the original film reel. It continues to be consulted today by religious studies scholars, as it is considered to be one of the few audiovisual records of Daitokuji temple life of the time.

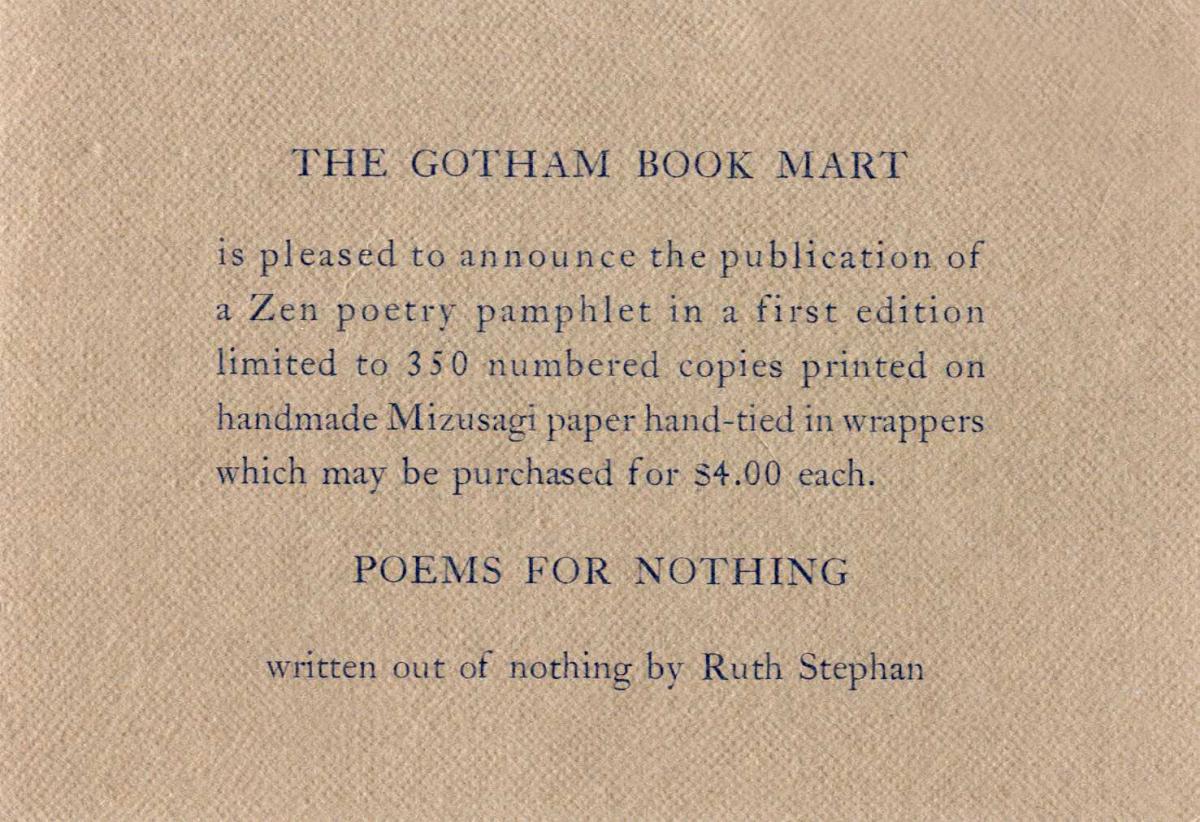

Stephan’s third book of poetry, Poems for Nothing, was published by Gotham Book Mart in 1973, the year of her death. On voca, you can listen to Stephan read some of the work from Poems for Nothing in 1971, two years before the book was published. The reading also includes a number of Stephan’s uncollected poems—reminders of a creative life well lived, but too soon ended.

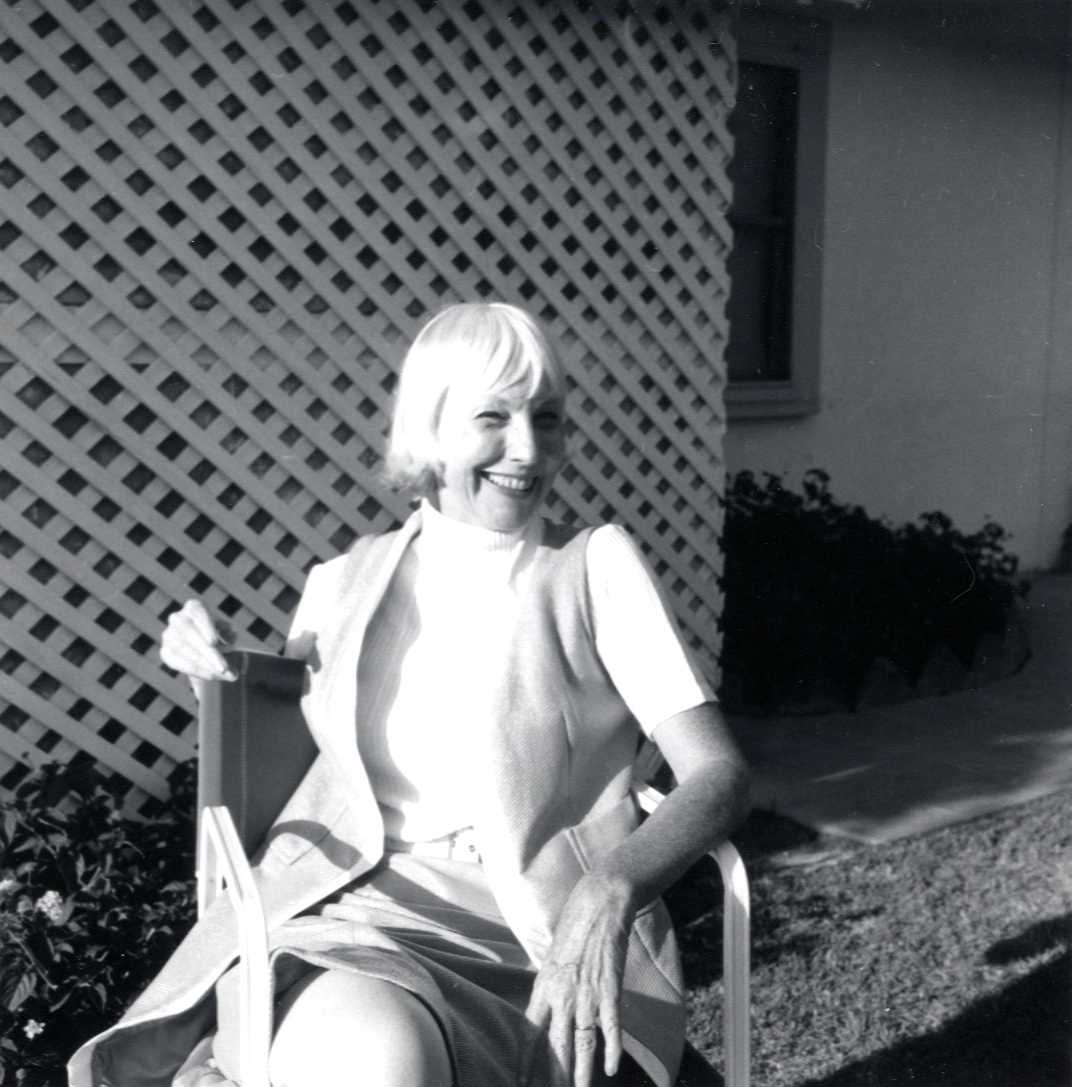

Intrigued by Ruth Stephan’s creative life and legacy? It’s easy to learn more. Come to the Poetry Center’s library to read any of the books featured here, or listen to two recordings of Stephan reading her poetry on voca. Our collection also houses numerous images of Stephan during the 1960s and 1970s, such as this one by the Poetry Center’s first director LaVerne Harrell Clark.