Below is a conversation between Jon Riccio, author of AGOREOGRAPHY and frequent interviewer for 1508, the Poetry Center's blog, and Sarah Gzemski, the former curator of 1508. After hosting so many of Jon's in-depth and instructive interviews, we knew we wanted to interview him about his work as well.

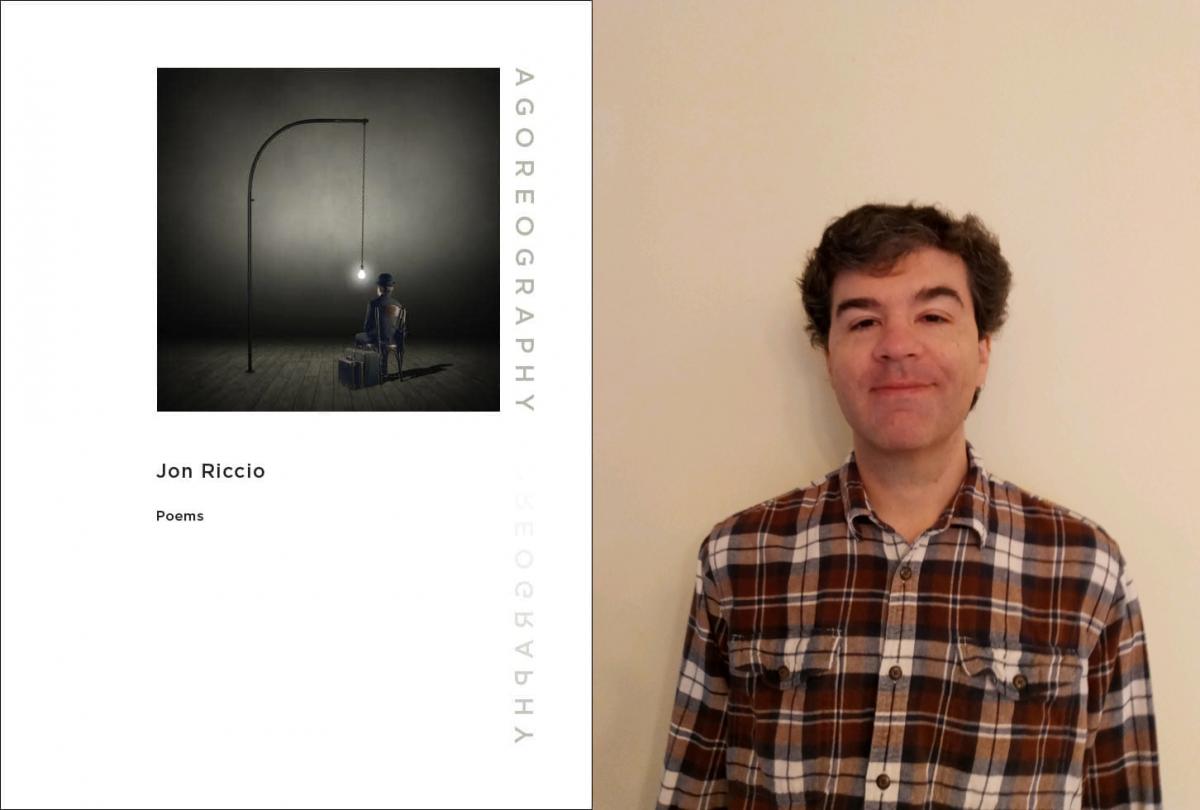

Sarah Gzemski: Jon, after reading so many of your interviews on this very blog, I’m so excited to be talking to you about your own book: AGOREOGRAPHY, out now from 3: A Taos Press. AGOREOGRAPHY delves into some heavy subject matter and trauma, but one of the feelings that reading the book most evoked for me was joy. At the end of “Eating,” there’s a description of this kind of tension: “I saw a shooting/star reflect off a pod of Tilt-a-Whirls,/supposing rides follow taxonomies//similar to how I depersonalize/down to a monosyllable/for phobia’s sake.” Often I’d be reading a phrase expecting one word and getting another, winding up down a rabbit hole of associations, yours and mine. Can you talk about your relationship to language and play?

Jon Riccio: Thank you for this opportunity to discuss my work, Sarah. The Poetry Center was instrumental to my MFA experience beginning in the fall of 2013 when I volunteered reshelving books, then that spring when I served as a digital projects intern. I have an Excel file, “JR Poetry Library,” with a sheet titled “Learned through Voca” (UAPC’s audiovisual archive)—Claribel Alegría, Nora Marks Dauenhauer, and William Kloefkorn among the writers whose readings I digitized, composed metadata for, and cross-referenced their poems’ spoken and printed versions. Staff members Sarah Kortemeier and Wendy Burk were as vital to building my knowledge that semester as Jane Miller, who led the poetry workshop. It was Wendy who gave me the opportunity to interview Fady Joudah and lead a small presentation on his opuses when he visited in February 2015. The Poetry Center, Sonora Review, and The Volta Online, with their Tucson connections, always said Yes when I queried for interviews. Your generosity through the 1508 blog allowed me to steward both colleagues and poets I’ve never met. Also, congratulations on becoming the Executive Director of Noemi Press. Ruth Ellen Kocher’s Ending in Planes (published by Noemi in 2014) was a must-buy after I discovered that she created the gigan poetry form.

I appreciate your observation about the play aspect in my poems. The earliest ones I wrote involved what I call vocabulary shopping, a pedagogical approach that, ironically, involves no financial transactions, just curiosity and observation. I trained as a classical violist, then went into fundraising. The bulk of my lexicon until the 2010s was music- and philanthropy-based. Tessitura. Hocket. Donors who were LYBUNT or SYBUNT (Last/Some Year But Unfortunately Not This one). My mid-thirties were getting serious about poetry time. Highly improbable scenarios, such as a broken-hearted bourbon vendor becoming the world’s eighth continent or mannequins who give birth to jack-in-the-boxes while selling teeth online: these were focus areas. My alcohol knowledge is three deep. Guinness, White Russians, and Mike’s Hard Lemonade. Well, that’s not enough to flesh out a double abecedarian about a vendor who steals Antarctica’s spotlight. Vocabulary shopping saw me visiting wine and spirit establishments with pad and pen, ogling labels for words unfamiliar to me. Immersion via spectatorship. The same routine worked for poems about electronics and off-kilter prodigies (kilowatts, wunder-plumbers, teenage reptile wranglers—hello hardware store, bongiorno Petco). The greatest gift one gives a rabbit hole? A Rolodex.

Formative collections where diction and imagination cohere include Sherwin Bitsui’s Shapeshift, Cathy Park Hong’s Engine Empire, and Lo Kwa Mei-en’s The Bees Make Money in the Lion. The first book I read that preached all linguistic bets are off was Tom Robbins’s Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas, leant to me by my friend Elizabeth Forest in 2011, who I met as a board member for a food-justice organization. The moral of this answer? Volunteering often leads to writing breakthroughs.

SG: Along these lines, in the Afterword to the book, you propose a new poetry movement: The Confurreal or Confessional Surrealism, something you carry into even your About the Author pages, eschewing what we think of as a traditional biographical statement. For me, some of the tenets you list of The Confurreal (“Disclosure and puzzlement.”) called to mind how often I see a headline or experience something that feels like it would have been too absurd to comprehend ten, five, three years ago. What draws you to surrealism with a more personal context?

JR: A favorite Audre Lorde line, “I don’t want to write a natural poem” (“Eulogy for Alvin Frost”), I taped to the wall of an old apartment. It was a daily reminder to stray from convention by taking the surrealist’s route to work. I don’t want to discuss Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and agoraphobia in natural terms because my experiences were incomprehensible. One month, I was on track to a professional musician’s life, the next I was relying on a friend to bring me food because grocery stores were triggers for OCD episodes, those years a tug of war between boggle and baffle.

There’s Rachel Zucker’s article, “Confessionalography: A GNAT (Grossly Non-Academic Talk) on "I" in Poetry” that I read in Susan Briante’s Fall 2014 craft class which covered experimental approaches to autobiography, Joe Brainard’s I Remember, Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day, Carmen Giménez’s Milk and Filth, and Megan Volpert’s Only Ride among the texts. One of the takeaways from “Confessionalography” states:

“Romantic poetry is the lightness of a soufflé about to fall. Autobiographical Poetry is a raw egg with or without salmonella. Autobiographicality is a hard boiled egg with or without a beginning art student in the background practicing chiaroscuro. Confessional Poetry is a hard boiled egg with a serrated knife lodged in its center and a tiny tear drop of blood on the knife's handle. Confessionalistic Poetry is half a deviled egg, with no sign of the other half except a thin snow drift of paprika on the white plate.”

Inspired by Zucker, I respond:

Surrealism is a party streamer. Twist it right and there’s a ‘Kodak moment’ for what plagues you. Surrealism is a bath at broth temperature in an anti-gravity chamber, the luxury that lets one associate in directions unplanned. It’s inheriting a rocket factory and the Fabergé estate on the same day. Confessionalism is the garage for trinkets and liquid hydrogen alike, The Confurreal its parking attendant.

SG: You mentioned your background as a trained musician, a background that feels like a spine in the body of this book – notes, lessons, concerts, bops, Stravinsky, Bach. Poetry and music, of course, use so many of the same basic (in this case, meaning base-level) words: rhythm, meter, etc. I love to talk about the musicality of a poem. I’m less interested in the technical differences between the two arts than in your experience of “doing” music or “doing” poetry. How is “doing” different or the same in the context of writing your book?

JR: I am beyond grateful my ears did viola first, writing second, all thanks to a trio of impactful music instructors, Karey Sitzler, Richard “Leo” Hazen, and Roland Vamos. My first decision about dedication came in seventh grade: do I join Kalamazoo Prep String Orchestra, which rehearsed at the same time as Saturday morning bowling, or stick with the pre-teen ten frame? Alto clef bested lanes. Viola became my primary focus the summer before tenth grade, local accolades a nifty result. By around November of junior year, I was practicing three to four hours a day, plus ensembles. I enjoyed the improvement process more than recitals. Repetitive études, run-throughs: a metronomic paradise. Give me the empty stage for recording over the full auditorium where it’s me as solo act, sonata duo, or string quartet member. A beloved ghost-town-of-a-concert-hall memory: Oberlin, Ohio, Super Bowl Sunday 1998, the Green Bay Packers, and cutting an audition tape for a music festival I really, really wanted to attend. I do two takes of a Bach fugue then head to a party. The acceptance letter came shortly before Spring Break. And, holy crystal ball of writing talent at Oberlin during the late ‵90s—Cathy Park Hong, Kiese Laymon, Chris Santiago, Rumaan Alam.

“Doing” music was about time investment; if you drill it, proficiency will come. Proficient, your performances probably won’t crash and burn. Five-hour practice days max. I don’t think I ever put this length of day into my creative work. PhD papers, proofreading marathons for journals or anthologies on which I serve, maybe, but allocating that to a poem between the time I wake and sleep? No. There were some three- (perhaps a rare four-) hour sessions during the MFA, especially the first semester (thank you, Farid Matuk’s workshop and Alison Hawthorne Deming’s craft class). Viola Jon, who carried an alarm clock from practice room to practice room, would be mortified by poet Jon and his current regimen of fifteen to twenty minutes in the morning, bumped to forty or fifty when I send drafts to readers-for-life, as was the case today.

The “doing” of AGOREOGRAPHY has musical parallels aplenty. Dress rehearsal number one: An early draft titled The First Agoraphobe in Space was my December 2015 MFA thesis. Not unlike flowers in a post-recital receiving line, I’m gifted a plastic doll face by committee member Ander Monson. Dress rehearsal number two: the modified version of AGOREOGRAPHY I submitted to Andrea Watson at 3: A Taos Press, plus some poems eventually excised from the manuscript, becomes the creative dissertation for my University of Southern Mississippi PhD defense, Valentine’s Day 2020. Lunch with my chair, Angela Ball, 1990’s Total Recall, and jeans shopping were my post-defense rewards. I expanded the manuscript that summer. We’re at the “private lesson” musical-equivalent phase when Andrea’s input saw me interrogating the collection’s merits and shortcomings the same way my instructor at Oberlin, Dr. Vamos, worked collaboratively with me. Example: my fourth finger needed strengthening, so together we arrived at the solution: Gavrilov’s opus 1 exercises. Dress rehearsal number three is accompanied by an email, “Jon Riccio AGOREOGRAPHY Final Copy of Manuscript,” sent to Andrea on January 26, 2022. The efforts I’ve taken since June’s publication (social media, interviews, reading inquiries) are hopefully generating the promotional momentum to get the book “out there,” much like an Oberlin tradition where we borrowed the Conservatory’s fabled locker list and plastered friends’ instrumental storage spaces with recital invitations. Landing sixteenth-note runs in the second movement of Rebecca Clarke’s Viola Sonata is one skill. Succeeding at the trifecta of Xerox, paper cutter, and midnight flier distribution is another.

SG: I love your description of the process of AGOREOGRAPHY moving through its early drafts to its current book form and noted here that though the investment of time wasn’t hours daily, it did take seven years from those early drafts to get to where the work is today. Sometimes it feels like there’s this (honestly, capitalist) pressure toward productivity and publishing as soon as possible post-MFA. I know I’ve felt that, certainly, and had to come to a comfortability with my own pace as a writer. Can you speak to those pressures at all? If not, how do you view them?

JR: I thought I’d hit the publication ground running as soon as the MFA started—like, first cactus I see will be covered in acceptance notices instead of thorns. In actuality, the first poem published during my Tucson trek occurred on 2/1/14 thanks to a journal called Bird’s Thumb. This fell on the weekend of a wonderful late-afternoon-to-late-night cohort gathering. The day was a combination of food, friendship, and a few stanzas lucky enough to find a home. What I remember most about that event? A bathroom’s mermaid switch plate, folklore hybridized to electrician zenith.

The patience lessons poetry tries to teach me? They pseudo-finally made an impact when I realized that stewarding other writers is as important as a high-tiered publication. The fulfillment found in those UAPC, Sonora, and Volta interviews helped take my snap judgments about worth (merit, merit, merit: that’s the name of my next dog) from field-sized to fishbowl. Currently, I defray letdowns by expanding my love of creative-writing pedagogy, authoring a monthly craft article called “Teaching Takeaways” for the website 1-Week Critique, the brainchild of Arizona alumni Matthew Schmidt, Adam Al-Sirgany, and Ingrid Wenzler. Each article walks readers through how a selected poem is constructed, line-by-line. I include a synesthetic rendering and closing prompt. They began as emails to my Spring 2020 undergraduate poetry students at the University of Southern Mississippi as a way to keep them writing over the summer. Rather than entire poems, I focused on excerpts, as such:

From Randall Mann’s “Monday” found in Breakfast with Thom Gunn:

Look: wildflowers bloom in the streetcar tracks;

a syringe lies in the grass. It isn't

beautiful, of course, this life. It is.

See how Mann contrasts two easily observable images, the first being nature’s interaction with

a) something human-made

ai) having to do with transportation

aii) pertinent to Mann’s city of residence, San Francisco

The other image is something destructive, discarded. The ugliness of everything that syringe stands for repels the abstraction of beauty. Mann exits with a simple declaration, two words, four letters. Extreme compression. His declaration contradicts the statement that came before.

So …

An observed image

The organic coexisting (making its headquarters) with the inorganic.

Plus

Another observed image

A harmful object among the organic.

Plus

Commentary about the images in as unadorned language as possible.

This example is place-specific, but the carryover is universal.

(Back in USM-locale mode): Think about this the next time you see that bluish sculpture across from the Hattiesburg Public Library, or those arches that signal the start of the Parkhaven neighborhood. Observe how these interact with the natural world. You can even photograph them if you're on a walk or stopped at a light. Then, keep an eye out for litter, shattered glass, demeaning graffiti. Pair the positive and negative images together like Mann does. What declaration can you generate based on this pairing?

Big Takeaway: Let the Observations Write the Poem for You.

These emails to my former students passed many a day during the 2020-2021 lockdown. That spring, Matthew and Adam invited me to broaden the format for their site. Fast forward two-and-a-half years and Jaydn DeWald is November’s Takeaway featured on social-media posts and as part of an email recipient list that’s just under 200.

How do I tread the Productivity Gorge? By reframing the non-submission work I create as shareable knowledge that might make its abode in someone’s draft or lesson plan.

SG: Finally, what (in either a writing or broader sense) are you working on now, post-AGOREOGRAPHY’s release? What are you reading? What excites you here at the end of 2022 about poetry?

JR: Thank you again, Sarah. The 1508 blog is such a stewarding, conversational environment. I’m reading Mai Der Vang’s Yellow Rain, having been a fan of Mai Der’s work since coming across her poetry during the Mauve Issue at Fairy Tale Review. Yellow Rain’s opening poem “Guide for the Channeling” tells us, “I have tried with//all my limber to keen a/credo of justice,” its final lines, “I have been gardening myself/into this remembrance.” Mnemonic flora, compelling. I’m also finalizing my syllabus for a nonfiction workshop at the University of West Alabama, Beth Nguyen, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Elizabeth Frank, Felicia Rose Chavez, Jesmyn Ward, Joseph Holt, and Amy Tan, its authors.

Writing-wise, I recently finished a class with Emily Wolahan, a dynamite generative workshop leader. It resulted in six drafts that explore Stonehenge and Saint Jerome, among others. These will boomerang onto a winter revision pile along with abecedarians whose themes all but dossier the parade float that is 80s television. Jo, Tootie, Blair, and Natalie weren’t going to Fact find themselves.

Excitement is friends’ forthcoming collections—Summer J. Hart’s Boomhouse, Charles Kell’s Ishmael Mask; editorial proofing on FTR’s Rainbow Issue “dedicated to queer fairy tales written by queer writers;” cheering recent releases by Emma Bolden (The Tiger and the Cage) and Sandra Simonds (Triptychs); a word bank awaiting its next free write; anyone who discovers The Confurreal and wants to chat; those Poetry Center steps leading to the workshop room upstairs.

A decade ago, I was building my MFA application packet under the guidance of John Rybicki and Traci Brimhall, employed at a Michigan food bank, and reading Carol Ann Duffy’s The World’s Wife. Per her poem “Mrs. Beast,” “At last it all made sense.”

Sarah Gzemski is a poet. She is the managing editor of Noemi Press and the interim financial coordinator at the University of Arizona Poetry Center. She is an editor and book designer living and working in Tucson, AZ, the ancestral and current home of the Tohono O'odham and Pascua Yaqui people. Her current manuscript about growing up an evangelical pastor's daughter grapples with fundamentalism's effects on her girlhood/womanhood and confronts its nationalist rhetoric and roots. Her work has appeared in Poetry, Bone Bouquet, Four Chambers, and Cartridge Lit, among others.