The photos stayed hanging up in the hallway of my parents’ house.

My brother killed himself, and the pictures still stayed up. These pictures were very haunting for me."

_____________

Diana Khoi Nguyen is a poet and multimedia artist. She is the author of the poetry books Ghost Of (2018) and Root Fractures (2024). In both books, the interplay of text and photograph creates layers of language, silences, and ruptures. Her work grapples with her brother's suicide, family stories, belonging and separations. "There is nothing that is not music," a line in one of her poems says, and her poetry brings that music to life. Curious to know more about Diana's creative process, I reached out with a few questions. The following interview comes from audio conversations passed back and forth through email.

Amy Smith: I have been reading Ghost Of and your newer book Root Fractures, and I love what you are doing with text and photograph and shape on the page. Prior to putting together the book Ghost Of, were you writing experimental poetry, or was that a new experience that came from working with the images and photographs?

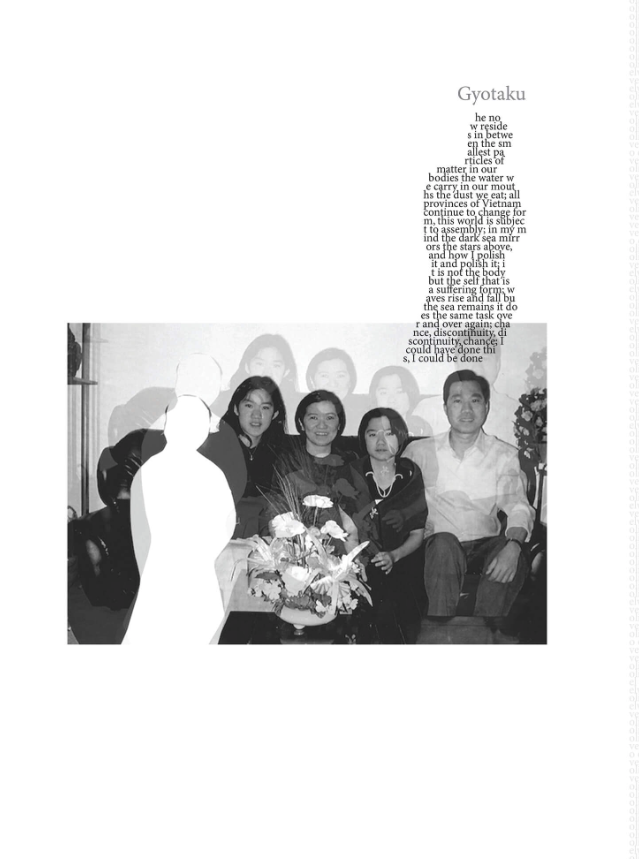

Diana Khoi Nguyen: Prior to putting together the book Ghost Of, I wasn't necessarily trying to write experimental poetry, and I definitely was not working with text and image, although I had worked with text and image as an undergrad years before. My experience for working with the images and photographs is precipitated by the death of my brother, his suicide, and reconciling with the images that he left behind. Two years before his death, he cut himself out of these family photographs; we didn't talk about this in the family. The photos stayed hanging up in the hallway of my parents’ house. My brother killed himself, and the pictures still stayed up. These pictures were very haunting for me.

Around the first year anniversary of his death, I tried to confront them and work with them in some fashion, in a hope to un-haunt myself and reverse the negative valence that these images had. So it was kind of an accident, but was also precipitated by my brother's death, what he left behind.

AS: That's powerful work. I am thinking especially of your triptychs. The cutout shapes contain text that is separate yet related to the prose that contains the empty space, and I also feel like the empty space does not lose content in the emptiness. Does that make sense? It is kind of paradoxical. I wonder if that was intentional?

DKN: I never thought about it as being paradoxical, but I understand what you're saying. I mean, everything I did was both intentional and also not. I wanted to use the photograph. It’s cut out as a stencil, and I was working with that as my boundary; it forced my line breaks. But I wasn't trying to wield empty space in any particular way. I was just really trying to mimic what the photograph is doing and work within that space.

AS: It's like silence, form, and the space in between. Do you think about these layers of meaning when you combine photo and text?

DKN: Maybe not consciously. When I combine imagery and text, I'm really just trying to surprise myself. Maybe on a subconscious level, I am thinking through meaning, because I don't want to make work that feels like nonsense to people. But I'm also not trying to make work that makes sense to everybody. So I'm really just trying to find stuff that surprises me. Work that sparks enough sense, but still eludes me in some way. There is still a mystery in the work for me, but also work that is highly emotional, even if I can't pinpoint why.

AS: There is a YouTube video where you read one of your Triptych poems, and the way you read highlights the emotion. The video shows the text, and your reading includes the empty space. There is something really powerful about those silent spaces. I wonder if there is anything you want to say about that?

DKN: I think when I first started to read the triptychs, I didn't read the hard silences. I would read the words, and project them on a screen. Then I realized: I'm not reading it the way it's written. So I started to read the space. I tried to read the silence. I'm thinking here about the page as a form of sheet music; to read both the notes and the lack of notes. I'm really glad I did that, because I think it enacts the fissure. I think that's the right word–– the fissure that happens, or the rupture that happens when there's a sudden death in a family. I feel like the form really captures that feeling. So when I read it out loud, it's like I'm in the momentum of the line. “I'm listening to a needle drop.” You know, you have this jolt of sudden death in the family, and you stop what you're doing. But then you're still alive, and you still have to go to work, or you still have to go to the restroom. You still have to feed yourself, and you have to start up again, which is kind of absurd. And then you remember that he's dead, and it's like everything stops. And so I feel like that form of reading really enacts that experience for me, and grief in the aftermath of a death in a family.

AS: There's so much here in your response. I love what you are saying about the way hard silence mimics the sensation of a sudden death. I can really feel that. As poets, we think about the way form reflects the content, and the work you are doing here underscores that relationship in an astonishing way. I can clearly hear the music in your work. I think of the way music and sound are both possible because of silence. Were you thinking about music when you created these pieces?

DKN: I listen to music when I compose. While writing Ghost Of, I was listening to Max Richter, the composer. The soundtrack from The Leftovers, and his recompositions of Vivaldi. I'm a huge fan of his work. I think there's something about when you listen––it's not like I'm transcribing the music, but it informs the undercurrents of how I compose. And when I was organizing the manuscript, I actually retitled poems so they adhered to a musical theme. Some of the poems are called Overture or Reprise or Coda. I thought of them as various units of structure within a musical composition. I kept thinking about how, when a person is dead, that's the only time we have true silence from them. There's no such thing as silence outside of death. There's just extreme quiet, but not silence. So I was thinking about silence versus lack of silence. Soundlessness versus sound making. I'm really grateful for your thoughts and observations here.

I kept thinking about how, when a person is dead,

that's the only time wehave true silence from them.

There's no such thing as silence outside of death.

AS: Thank you, Diana. I really appreciate you sharing all of that. It feels like a really powerful backdrop to your work. In many ways, Root Fractures seems like a continuation of the content you explore in Ghost Of. I am curious about the role that ancestry plays, and how the history of your family plays out in the story that is both past and present. Did you engage in research around family and cultural history, and what was that process like?

DKN: I engaged in a lot of research. It was part of my PhD. I did all these oral history conversations with family members, but also folks within the diaspora. A lot of that research doesn't appear in the book, because I didn't feel like they were my narratives to share or to work with. What I did keep in Root Fractures were what those narratives and oral histories made me think about. And of course I have bits of my father's and to a certain extent, some of my mother's and my grandmother's stories. Honestly, when I was doing that research I wasn't trying to write Root Fractures. I was just curious, and capturing these narratives. I would have a program transcribe most of it, but none capture Vietnamese or accented English very well, so I had to go in and listen. I think in listening to the audio and trying to fix the transcription, it gave me a very specific kind of intimacy with those narratives, and with what I was hearing. That changed my relationship to those people, especially their family members, which then shaped how I write about them, and how I think about them.

AS: I am thinking about all the visual images you use in your work. Do you think poetry changes for the reader when text is combined with visual imagery?

DKN: I don't think poetry changes for the reader, but it does have a different experience. Instead of translating the words on a page into an image in the mind, we immediately receive an image. But I would argue that all language–– the alphabet, words, those are all images that mean something. They're signs and symbols that then get translated into a visual image. So there is something different that happens with a photograph. There's not the same kind of translation that might happen in one's mind. For example, if you say the word chair, it is very different from seeing a picture of a chair, because there's so many different kinds of chairs. A reader might imagine different types of chairs depending on how they grew up and the kind of chairs they work around.

AS: You do amazing work as a multimedia artist. What are you working with now?

DKN: I've been working in video, primarily single channel. But also multiple channels. And by that I just mean how many screens. Right now, I've been working on installation videos, installing multiple screens in a space. It's been fun to think about what constitutes a screen. Something that I did last month was project some pieces in my backyard at night on the trees and the grass and the leaves. It's impossible to do now, because all the leaves have fallen. But it was really kind of amazing to see what a moving green screen image would look like.

I would argue that all language—the alphabet, words—

those are all images that mean something. They're signs & symbols

that get translated into a visual image.

AS: Do your videos include your textual poetry?

DKN: The video work does not usually have text accompaniments. But I think of the pieces as poems. Poems as videos. And they're primarily a visual and musical medium. Sometimes I’m using either a Max Richter composition, or an original sound accompaniment, not necessarily music. For instance, in one piece I use some humming.

The content that I was projecting onto the trees was some of the old video poems I had done 8 years ago of my siblings and me playing as kids. These are seen through a green screen of my adult self wearing a green dress; and in place of the green dress there’s a little keyhole portal into the archival video. So the adult body is walking in the terrain, but through the dress of the adult body you can see the 3 kids playing.

AS: I took a look at your videos, and they are so interesting. I love this idea that poetry can be visual as much as textual. Most of my questions come from the perspective of a textual poet. So I am curious if there is anything regarding your work that you wish an interviewer would ask about that always gets overlooked?

DKN: People always ask about the image and text. And I’m grateful for it! But I do feel like the work is funny at times–– nobody really talks or asks about that specifically. Probably because the subject matter is so personal and sometimes difficult. It can feel, maybe, kind of glib to talk about the humor in the work. But I think that there is something hilarious at times—not "haha" funny, but more like there's an absurdity to this kind of trauma and difficult content. I can't help but allow for the humor to shine through.

Crop it, blur it, mess it up.

I love thinking about nonverbal forms of play

before entering into language.

AS: Yes! Life is like that, right? In the worst tragedy, humor shows up, and sometimes I think it is the absurdity that gets us through the hard times. I’ve been thinking about the necessity of creativity in times of darkness–– do you think that art, maybe more so than other disciplines, is so necessary because it has the ability to hold both grief and joy, both trauma and humor?

DKN: In the worst tragedy, humor shows up. Absurdity absolutely gets us through. I think that art, especially because it's such a huge field and comprises so many different manifestations, is such a freeing form and can hold an abundance of emotions. Because there's not necessarily linearity. It doesn't have to imitate the structures of everyday life as we know it. It can mimic the turmoil and the confusion that we feel internally. And we can do that through so many different materials. A mixture of media, for sure. I think that's why I'm drawn to it. I think the only other field that can do this is actual comedy, like stand up comedy, which I watch a lot of!

AS: What advice would you give to a poet who wants to expand into working with multimedia and/or text and image?

DKN: Oh, I think my first advice is to identify material that's personal to you, that you have strong emotional responses to, and find an entrance point into working with that. Maybe that's responding to what's not in the image. Responding to what the image evokes, or responding to the silence in the image. And if there aren't any words or language at first, just play with the image. Crop it, blur it, mess it up. I love thinking about nonverbal forms of play before entering into language.

AS: Such great advice. Diana, thank you so much for taking the time to share your work and your process.

DKN: Thank you again for all these questions, and I hope we get to cross paths one day soon.

___________

A poet and multimedia artist, Diana Khoi Nguyen is the author of Root Fractures (2024) and Ghost Of (2018), which was a finalist for the National Book Award. Her video work has been exhibited at the Miller ICA. Nguyen is a Kundiman and MacDowell fellow and member of the Vietnamese artist collective, She Who Has No Master(s). She's received an NEA fellowship and a 2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award. She teaches in the Randolph College Low-Residency MFA and is an Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh.

Amy Smith is a poet living and writing in Northern Nevada. Some of her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in several places, including: Humana Obscura, Gyroscope Review, contemporary haibun online, and the Wee Sparrow Water Anthology. Amy is currently pursuing her MFA degree in poetry through the low-residency program at the University of Nevada, Reno at Lake Tahoe.