artists are full people beyond their published work...

their published work only scratches the surface of who they are.

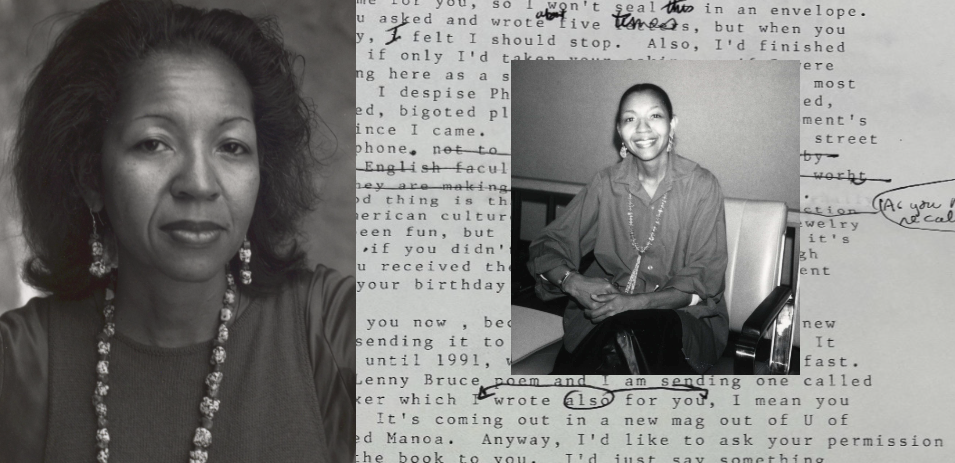

On this day, the poet would have been 78 years old.

Listen to Ai on Voca

When I was an MFA student in office hours with Professor Farid Matuk, I remember confessing how in my poems, “I wanted to be a cold, hard witch.” Rather than judge or cast me a confused look, Professor Matuk simply nodded and contemplated what I’d said. After a brief pause, he replied with, “Have you heard of the poet Ai?”

Cut to four years later, and I am inquiring at the front desk of the Library of Congress’ Manuscript Division Reading Room to consult the papers of this very poet, which became publicly available to researchers in March 2023, and comprise of over 18,000 documents related to her writing, teaching, correspondence, and personal life.

I had little idea of what I was going to find in Ai’s papers. I was not approaching them with a particular question in mind, just open curiosity about what she was like as a person off the page, outside the realm of her poems. What I ultimately ended up taking away from this research visit was learning about Ai beyond her work as a published poet and getting a broader sense of her life, and how artists are full people beyond their published work, how their published work only scratches the surface of who they are. I also learned about how much financial woes weighed on Ai, which just goes to show that publication fame does not necessarily equal fortune. Overall, the visit provided a more nuanced look into who Ai was, and how so much goes into the life of the artist aside from their public work.

"I bet you never imagined that the winner

of the 1999 National Book Award for Poetry

had to substitute teach high school

a year ago in order to survive...."

On my Library of Congress visit, I also felt empowered as a not only as a creative writer, but as a researcher. I recall the first week of my MFA, when Professor Manuel Muñoz spoke to my cohort about the under-discussed and often invisible, yet nonetheless crucial, labor of research for creative writers. I had never heard a writer articulate this before, and upon hearing Professor Muñoz’s remarks, I began to recall the times I had finished a book and found its final pages dedicated to footnotes, citations, and acknowledgements of a wide range sources the author consulted. To find out that Ai herself was an avid researcher herself only further connected these creative and investigative practices that had previously occupied separate categories in my mind.

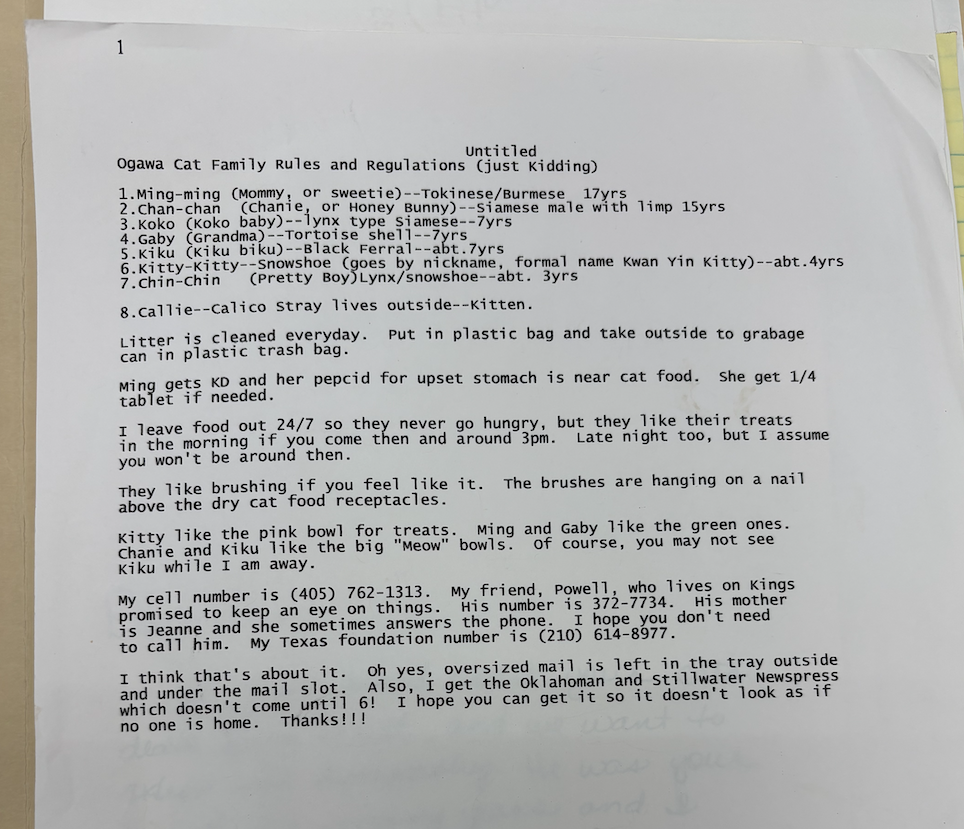

I honored the witchy proclivities that brought me to Ai’s work and began my journey into her papers with a folder about her cats. From saved vet bills to handwritten birthday cards to a condolence letter from neighbors upon one of her cats’ passing, Ai’s devotion to her feline companions was palpable. One set of instructions she typed up for a cat sitter was charmingly titled “Ogawa Cat Family Rules and Regulations (just kidding).” This document reveals that Ai had seven cats at one point, plus a stray she was feeding. She gave each of them distinctive names as well as nicknames.

Ai Ogawa Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Box 8.

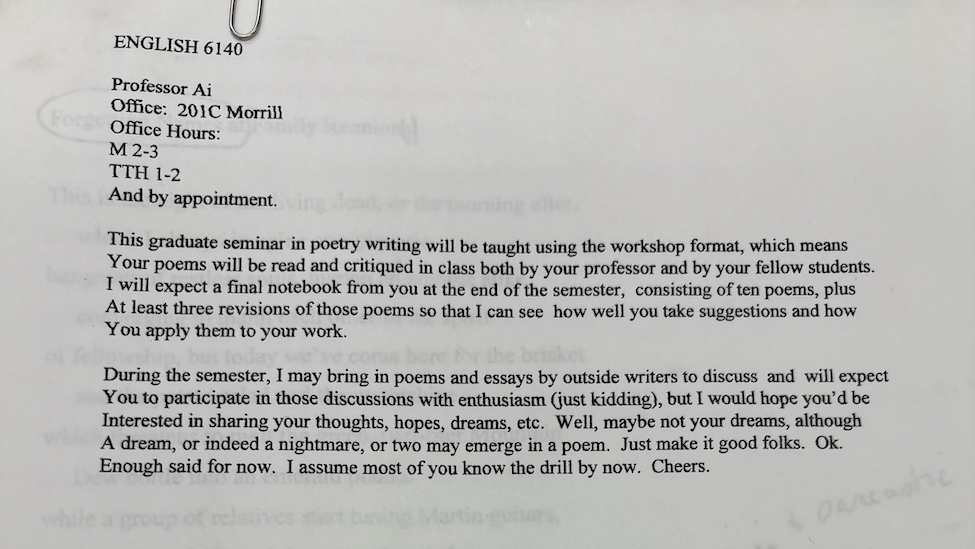

In skimming through my photos after the visit, this parenthetical, “(just kidding),” stuck out to me. I realized it is because the phrase also appears in an ostensibly different context within Ai’s papers: her teaching materials. On the front page of a graduate poetry workshop syllabus, Ai states: “During the semester, I may bring in poems and essays by outside writers to discuss and will expect You to participate in those discussions with enthusiasm (just kidding), but I would hope you’d be Interested in sharing your thoughts, hopes, dreams, etc.” She uses the phrase again in another syllabus: “Each class, we will read and discuss poems the students have turned in and from time to time veer from the topic at hand into unexplored territory, but always returning wiser and perhaps sadder, yet improved in our understanding of life itself (just kidding).”

Ai Ogawa Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

As an exercise, I wrote out each of Ai’s guidelines from these three separate documents without the “(just kidding)” to see how much the tone shifted:

“Ogawa Cat Family Rules and Regulations.”

“During the semester, I may bring in poems and essays by outside writers to discuss and will expect You to participate in those discussions with enthusiasm, but I would hope you’d be Interested in sharing your thoughts, hopes, dreams, etc.”

“But always returning wiser and perhaps sadder, yet improved on our understanding of life itself.”

On their own, these statements seem perfectly reasonable in their respective contexts—why kid about them? I read this aspect of her syntax as deflective, blanketing what could possibly be perceived as severity or intensity. I wonder if Ai was someone who had high standards for how she navigated her space, whether at home with her cats or in the classroom with students. Maybe, as a woman of color who eschewed various social norms—a single, unmarried woman with an unconventional profession whose work within her field was also in a category of its own—it was easier to take up that space of intensity in her poems rather than in such daily contracts, such as between cat owner and sitter, or teacher and student. As a woman, and as a nonwhite woman in particular, I understand all too well the tendency to water down my preferences. Would a man add a parenthetical of jest to these statements? Maybe the explanation is much simpler: Ai had a sense of humor. Or perhaps, since humor often serves as a recourse for discomfort, it was both.

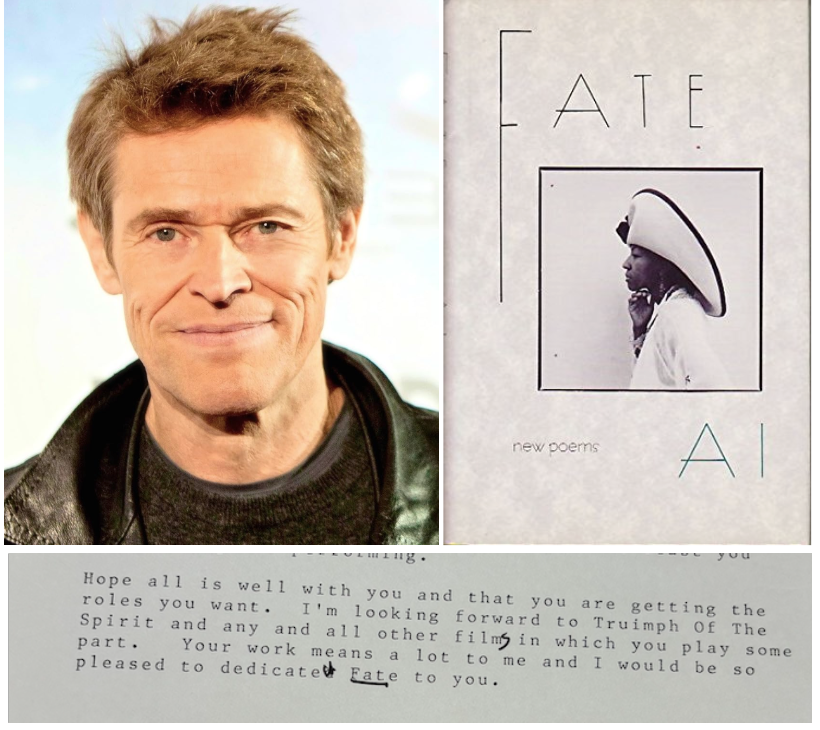

The next folder I opened contained quite the gem. Many of Ai’s poems are based on specific people, most of them dead, but one lucky living muse got an entire book of poems dedicated to him: Willem Dafoe. Yes, that Willem Dafoe. Ai dedicated her book Fate to Dafoe but first asked for his permission: “I’d like to ask your permission to dedicate the book to you…If I think of the book as a performance, then you as the muse are part of it.”

It was refreshing to see Ai explicitly name Dafoe as a muse. Often, this dynamic evokes a male artist falling head over heels for a woman, using her as inspiration for his artistic output yet dehumanizing her in the process.

Ai Ogawa Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Box 8.

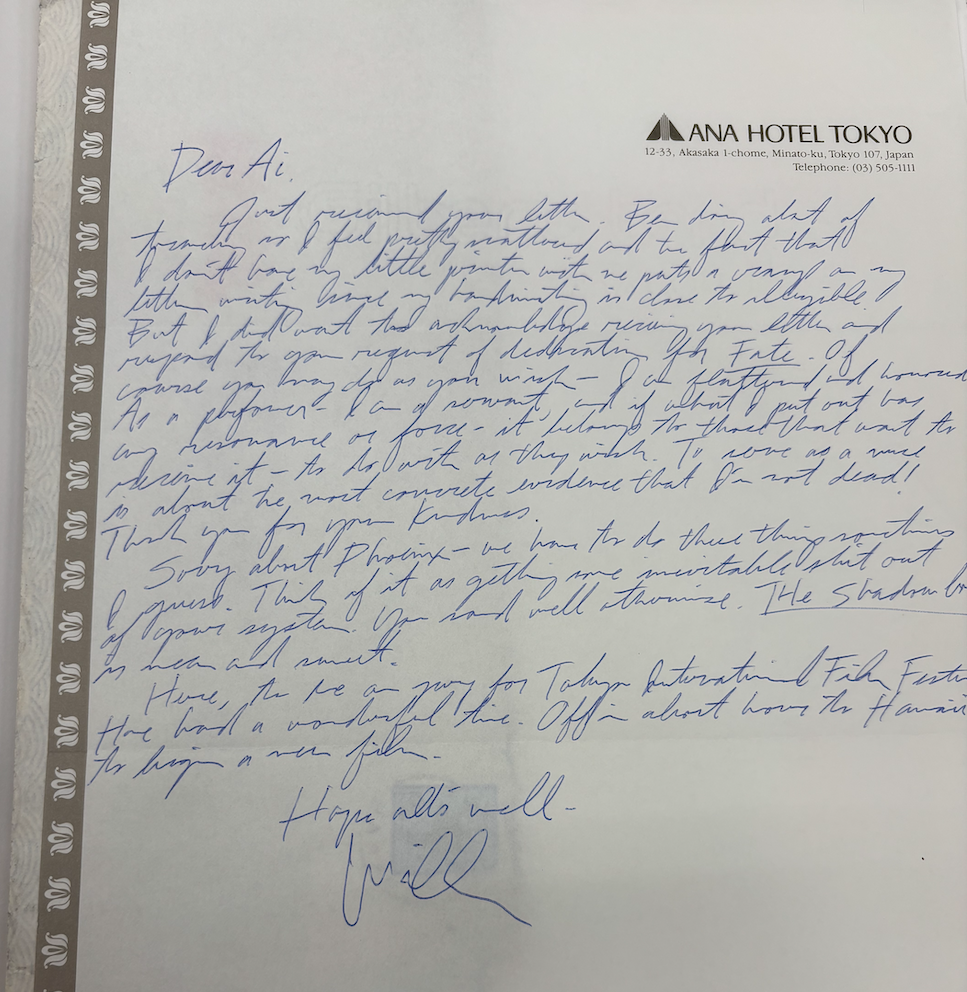

Dafoe responded to Ai’s letter requesting dedication permission, writing: “Of course you may do as you wish—I am flattered and honored…if what I put out has any resonance or force – it belongs to those that want to receive it – to do with as they wish.” I wonder if it took Ai just as long to read his penmanship as it did for me!

Ai Ogawa Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Box 8.

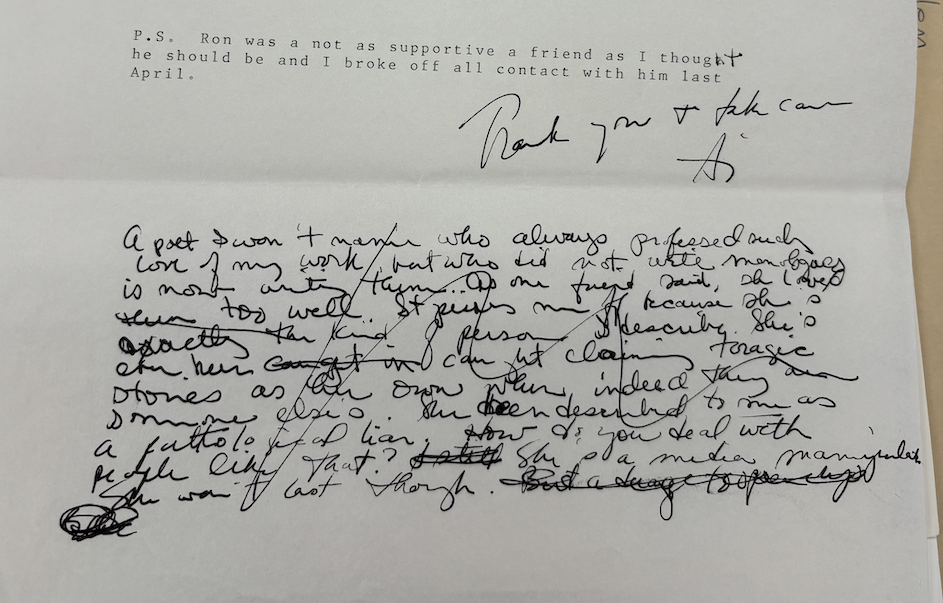

Ai’s correspondence with Dafoe also reveals her own vulnerabilities around the artist’s life. On the second page of the book dedication request letter, she asks Dafoe for advice on how to deal with opportunistic peers in one’s creative field: “A poet I won’t name who always professed such love of my work but who did not write monologues is now writing them…How do you deal with people like that? She’s a media manipulator. She won’t last though.” Parsing out this sentence also took some zooming in and handwriting study!

It is uncertain whether Dafoe read this plea for advice, since Ai handwrote this paragraph at the bottom of the typed-up letter draft, but I am grateful to have come across this etching of insecurity. Of course, this is not to underwrite the confidence in the zinger of a line, “She won’t last though”!

I did not expect to see any traces of Ai seeking out advice,

but of course, support and mentorship are so crucial for artists

trying to survive in competitive, underpaid fields.

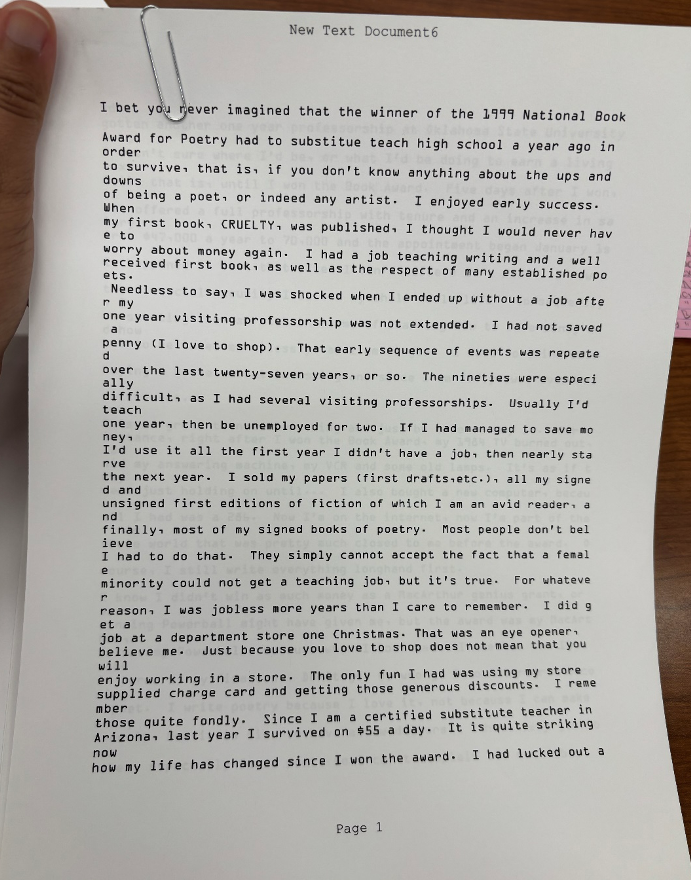

I did not expect to see any traces of Ai seeking out advice, but of course, support and mentorship are so crucial for artists trying to survive in competitive, underpaid fields. Indeed, Ai’s papers stand as a testament to the difficulty and instability of finding financial security as a poet. In a grant applications folder, there was a candid writeup where Ai states: “I bet you never imagined that the winner of the 1999 National Book Award for Poetry had to substitute teach high school a year ago in order to survive, that is, if you don’t know anything about the ups and downs of being a poet, or indeed any artist.” She goes on to detail how she also had to sell her papers, collection of fiction books, and her own poetry collections which she signed. It was poignant to encounter within Ai’s papers the explanation for why a chunk of them is missing.

Ai Ogawa Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Box 23.

Eventually, Ai obtained a tenure-track professorship at Oklahoma State University in 1999, shortly after winning the National Book Award for Vice. Looking through Ai’s teaching materials was a fascinating glimpse into what she was like at her day job. Based on the student evaluations I was able to read through, “Professor Ai” was full of personality, and I can imagine how, as her student, there would hardly be a dull moment in the classroom. One undergraduate wrote how, “Ai cares about the students and she only wants to help students learn. She tells stories like no one I’ve ever heard.” Seconding Ai’s storytelling abilities, another student expressed how the class “didn’t seem like a chore and Prof. Ai’s stories were entertaining too.”

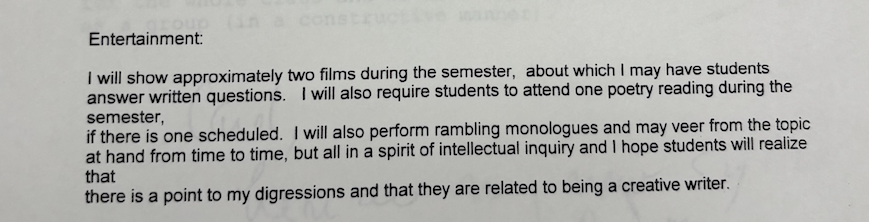

Ai seemed to have turned her penchant for the monologue in her poems to a pedagogical tool, and in one syllabus stated explicitly that she “will also perform rambling monologues and may veer from the topic at hand from time to time, but all in the spirit of intellectual inquiry and I hope students will realize that there is a point to my digressions and that they are related to being a creative writer.” Fittingly, Ai included these remarks in the section of the syllabus called “Entertainment."

Ai Ogawa Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Ai’s love for the monologue began in her own creative writing student days as an undergraduate at the University of Arizona, where she had former Poetry Center Director Richard Shelton as her first poetry teacher. In a grant application under the section “How Your Work Has Evolved,” Ai recounts: “My first poetry teacher, Richard Shelton, said the first person was the strongest voice when writing and when I experimented with it, I found I had a gift for it. I think when I started out, sometimes I wanted to shock readers, but I am beyond that now and am just writing.”

In this same grant application, Ai wrote that her reason for applying was to obtain funding for research she was conducting on her Native American ancestry. Her description of this project is a testament to how a writing endeavor can take much longer than the writer initially thought, and to how costly the archival research process can be: “I have been working on a memoir since about 1999, but as it involves a lot of research, it has taken me much longer to write than I imagined it would…All of the Plains Indian history is quite complicated…It can be quite expensive, i.e. one set of records from the National Archives cost over $800…what started out as a simple memoir has evolved into a memoir/tribal history…”

The application also includes the shocking detail that Ai apparently met and interacted with a serial killer known as the “Pied Piper of Tucson”—a fact which clearly made an impression on her as a poet who delves into the dark sides of the human psyche.

Ai Ogawa Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Box 23.

The grant application folder was fascinating, since these applications prompt artists to state the goals and intentions of their work as clearly as possible. The kind of writing required for grants is a genre in itself, and strikingly different from what one might encounter in an artist’s work, which does not always state these intentions so explicitly. Reading through Ai’s grant applications also served as a reminder that making art requires time and money, without which a project might be impossible to complete. Reading through this application caused me to view Ai’s writing through a lens I had not before, for I found a particularly moving line: “It seems to me that my Indian ancestors were able to survive not only by adopting and adapting to the white man’s ways, but in many ways intermarrying with them, as well as with African Americans and that is what ultimately saved the family.”

making art requires time and money,

without which a project might be impossible to complete

I was struck by how Ai framed how the resilience and adaptation of her family ensured their—and by extension her—survival. The theme of ancestry has been embedded in Ai’s creative practice from the start, beginning with her name, which she legally changed in 1973. “Ai” means “love” in Japanese. Ai’s father was a Japanese man with whom her mother had an affair. Ai graduated from the University of Arizona as an Oriental Studies major with a focus on Japanese. As I reflect on her chosen name after spending time with her papers, learning about this memoir on her ancestry that she never got to complete compelled me to think about how throughout her life, Ai preserved the love that was necessary for generations of her ancestors to adapt to the throes of American history: war, displacement, poverty, movement—all of which proves inextricable from race. The love and will to live required to survive hardship and trauma often do not look calm or pretty, but brutal, dark.

“Ai” means “love” in Japanese.

[...] throughout her life, Ai preserved the love

that was necessary for generations of her ancestors

to adapt to the throes of American history:

war, displacement, poverty, movement—

all of which proves inextricable from race.

In their intensity, Ai’s poems enact one of the most generous forms of love: shedding light on emotions and experiences that are often shrouded in silence and shame, which can help others feel less alone. The titles of Ai’s books spell out the facets of humanity that many would prefer not to acknowledge: Cruelty, Killing Floor, Sin, Fate, Greed, Vice, Dread, and the posthumous collection No Surrender. It was also an act of love for Ai to write openly about these topics, so that her readers, encountering the darkness of her work, can process the depth and breadth of their full humanity. In her grant application, I can also see her meticulous, laborious, and costly research process to uncover and honor this lineage as another act grounded in love. Yet Ai’s poetry contains an unmistakable edge, and does love also not involve risk, danger?

It is thanks to Ai’s example that in my own poetry, I feel less afraid to draw inspiration from themes such as power, fear, vengeance, and betrayal. Her deft use of imagination makes the poems feel like worlds unto themselves. Reading them feels supernatural, and I understand now why when I wanted to be a poetry witch, Professor Matuk immediately thought of Ai. Spending time with her papers made me blessedly aware of how she embodied the true meaning of “witch”: a woman at the height of her creative power.

________________________

Aria Pahari received her MFA at the University of Arizona and works as Library Specialist at the Poetry Center. Her poems can be found in The Georgia Review, The Margins, Inverted Syntax, and Waxwing.

The publication date of this post coincides with the poet Ai's birthday. On this day, the poet would have been 78 years old.

To learn about the enduring effect Ai has had on other contemporary poets, tune in to the Poetry Centered podcast, where four different poet hosts—Urayoán Noel, Douglas Kearney, Sumita Chakraborty, and Adrian Matejka—selected recordings of Ai for their episodes.