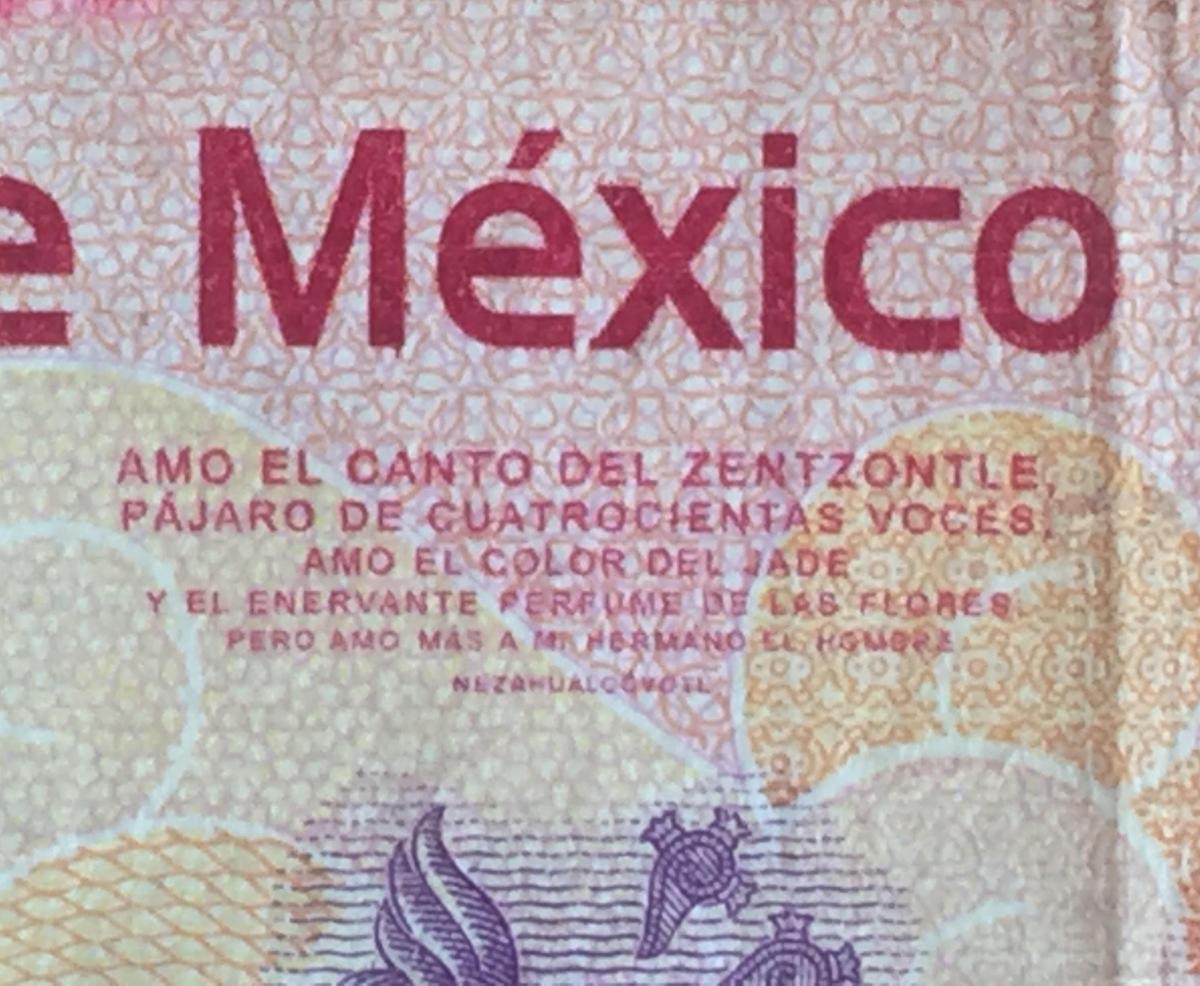

The bartender folds a one hundred Mexican Peso note into a rectangle and moves it into the light, above amber bottles of mezcal.

“This is my favorite poem,” he says handing me the small package.

He’s isolated five lines of the tiniest red text. I cannot read it, so he recites it from memory. First in Spanish, then in English.

Amo el canto del zenzontle

Pájaro de cuatrocientas voces,

Amo el color del jade

Y el enervante perfume de las flores,

Pero más amo a mi hermano, el hombre.

I love the song of the mockingbird,

Bird of four hundred voices,

I love the color of jade

And the intoxicating scent of flowers,

But more than all I love my brother, man.

—

The author stares back on the same side of the note: Nezahualcoyotl. “The Coyote Who Fasts” ruled Texcoco, a city-state of Pre-Columbian Mexico and part of what is now Mexico City. Sixteenth century European biographers wrote Nezahualcoyotl as a poet, philosopher, architect, and warrior. But in his book, Allure of Nezahualcoyotl, Jongsoo Lee writes that these chroniclers “interpreted the indigenous cultural tradition from the colonizer’s perspective.” The tradition he speaks of is Nahuatl song-poetry. Song-poems were written anonymously, passed down orally, altered inidivudally, and performed by groups.

However, in sixteenth century Europe, a poem had one author. The historians applied the same logic to the art of people they never met. Who could write these poems about beauty, philosophy, and the ephemerality of life? Historians needed an author to revere. They painted Nezahualcoyotl as a poet to fill that gap, but they also altered his legacy for European tastes.

They made up a story. Nezahualcoyotl surrounded himself with philosophers. He was skeptic of the polytheistic Aztec religion. He banned human sacrifice from his city. Suddenly he was a Christian and civilized author. Someone palatable to the family back home. It’s unlikely that any of this story is true. In fact, in most Nahuatl song-poems the opposite is described. Nezahualcoyotl didn’t ban blood sacrifice; he was devoted to the indigenous religion. He may have composed poems and painted, but many of the Nahua poems revered today for their philosophic beauty were not his work.

Historians furthered their story, by incorrectly translating song-poems. In chronicling Nahua poetry (the language that gave us “chocolate,” “avocado,” “chili,” and “tomato,”) historians read “de” as “by” rather than “of.” So “Song of Axayacatl Itzcoatl, Ruler of Mexico,”becomes “Song by Axayacatl Itzcoatl, Ruler of Mexico.” In these poems or songs, historians also interpreted “I am Nezahualcoyotl” as an admission of authorship. We know now not to take the I in a poem for an autobiographical I, but sixteenth century European historians took I as truth.

And so, an entire history is rewritten in translation from the Aztec pictoral and oral tradition to the European alphabet, just as history (or truth) is always lost in colonization.

—

Authorship during and before the Middle Ages can be grey. Perhaps the most well-known example of this is saint and composer, Hildegarde von Bingen. She is widely considered the first composer of music—not because she composed the first known pieces of music, but because she was the first to sign her work with her own name. Most medieval composers are known as “Anon.” Anonymous authors might be the result of oral to written translation. More likely, it was expected of musicians not to take ownership for their creation. Music was written exclusively in churches; it could not be claimed because it was a gift from God.

Did the author or authors of Nahua songs and poems lose their ownership in translation to written language? Maybe they never “owned” their work in the first place. “Owning” a piece of art could have been an affront to a higher power or, perhaps, taken focus away from their subject: Netzahualcoyotl.

The answer is rooted in way the song-poems were communicated: passed along by word of mouth. Nahuatl poetry was oriented towards the collective, even though some song-poems could be performed individually. The composer didn’t matter, because in oral tradition art is meant to be shared and individually altered or added to (the way a musician can cover a song and completely change its feeling and meaning). Nahuatl poems were collectively owned. They were different person-to-person, but in the end, the same.

—

Today, collaborative art acknowledges multiple authors, voices woven together in many different ways. An Army of Lovers by Juliana Spahr and David Buuck is loosely based on the authors’ own lives. The books grew out of “homework assignments” to get them out of their writing routine. One of the assignments was to write a biography of the other. The resulting book features the overlapping narratives of Demented Panda and Koki as they try to conjure a utopia, fueled by their dissatisfaction with poetry’s inability to affect social change.

In an interview, Spahr said that collaboration allowed her to take on subjects she was too scared to take on by herself. “I know that some of the talks I wrote with Stephanie Young were doing some work I couldn’t do on my own. Didn’t feel strong enough to do, didn’t feel like I could take the inevitable complaining on my own.”

Collaboration can happen in creating art and performing it. When Thalia Field came to the University of Arizona Poetry Center in 2017, she organized a chamber choir or readers to voice the characters in her book, Birdlovers, Backyard. Even the Poetry Center’s director, Tyler Meier, was once plucked from an audience by Craig Santo Perez to hold a can of Vienna Sausages during an audience-driven reading.

—

Even though this information is out there and readily available, Nezahualcoyotl stays on the Mexican peso because it’s not about authorship. The poem to the left of his crown is about loving one’s culture: its location, its familiar pleasures, and its people. The mockingbird, the color of jade, and the smell of a home in bloom are still important to the Mexican people. The Nezahualcoyotl on the peso isn’t the colonized dream, but a representative of Mexico’s indigenous culture which has so often been erased and rewritten.