The other day I was in a meeting where the last half hour turned into 45 minutes, and two men dominated the conversation and, in my opinion, harassed others (mainly women who also tried to speak) by aggressively repeating their same arguments over and over again. The day before that I was reading Rebecca Solnit’s “Men Explain Things to Me” which I noticed recirculating on Twitter. And around that time, I also watched the Instagram live recorded video of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez discussing the events of January 6 at the US Capital. She began by sharing that people who have been in abusive situations or relationships recognize the ways bullying, harassment, and abuse played out on the 6th, and especially in the ways some members of Congress wanted to just move on instead of holding the white supremacists--the rioters, inciters, and enablers--accountable.

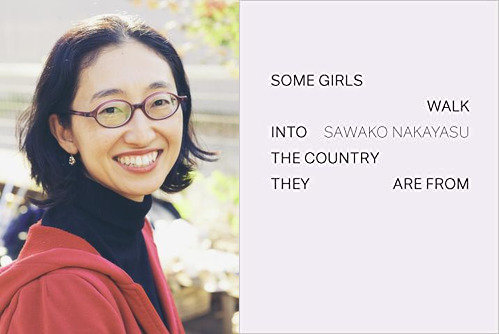

When I started reading Some Girls Walk Into the Country They Are From I already had a (mid)lifetime of feminist thinking and perspective that I was bringing to the book, though I didn’t really know what to expect beyond the title before diving in. And when I picked it up again half-way through--after having put it aside for a bit--in the time just before the Senate impeachment trial, the moments of shared recognition with the other women--in my recent meeting, with Solnit and her readers since that essay was originally published, and with AOC’s story as one of many stories that need to be shared--I felt the book even more powerfully. It may be that the pieces later in the book feel more hard-hitting because, like dealing with harassment as a woman or BIPOC person on a continuous basis, the feelings and effects accumulate; that reading, over time, might lead to a deeper perception of microaggressions and coded language. Or it may have been the moment during which I was reading. Likely, it’s all of these things, gathered into this cultural moment where we are trying as a country to face many things gone unfaced for so long, including different kinds of abuse targeted toward women.

The book includes pieces and translations by Genève Chao, Lynn Xu, Hitomi Yoshio, Kyongmi Park, Kyoko Yoshida, Karen An-Hwei Lee, and Miwako Ozawa, and includes writing in English, French, Japanese, and Chinese. Many of the titles include the word “girl” and in many of the pieces girl characters are named with letters (Girl A, Girl B, etc.). The pieces themselves range in form and style; a few include poetic line breaks and many are written as narrative prose. Most pieces are innovative in content as well as form, playing with language, syntax, and vocabulary, and making use of visual elements on the page. And because of the play and inventiveness, the pieces lend toward open interpretation while being grounded in feminist perspective--something that’s not a single or definable perspective but might be described more like a constellation of affinities, or oppositional points and intersections, layers and nuances. The showing and telling of seemingly nonsensical or child-like fantastical situations throughout the book also might be seen as a kind of complex network of experiences.

The “play” of translation is also quite animated in Some Girls. Versions of poems in the different languages are placed variously throughout, giving an effect of resonance as one progresses, and even more so if one can read even just a bit of the multiple languages; ideas and effects repeat like echos. Although there are included notes about contributors and translators, often it’s hard to tell the original piece from its translation, adding to the poetic slipperiness. And instead of literal and direct translation within or adjacent to each piece, the book instead has a kind of what Sawako calls “roguish” quality--when speaking of the process of translation more generally--of finding “different ways of being ‘true’ to the work I was translating,” (from The Conversant, cited in poetryfoundation.org). It also reminds us that often there is no literal translation, and instead the act itself is a kind of play of choices, syntax, interpretation, feeling, and more. In an email, Sawako reminds me of an earlier essay I wrote which included reflection on pieces from the Haiku for a Global Pandemic Facebook Group, and how some of those pieces in English, at that cultural moment, get at something that is often missed when we focus exclusively on technical details in haiku, like syllables, for example. More important is the “spontaneity of a poetic thought,” Sawako writes, that haiku as a kind of poetry-in-the-moment can offer.

Around this same time, Sawako gave a talk for the Columbia Writing program, and participated in a conversation after with Lynn Xu who is also a collaborator in Some Girls, and Susan Bernofsky. Reading from her poetic, hybrid essay titled, “Say Translation is Art,” just published by Ugly Duckling Presse, she further reflected on the idea of translation as process vs product, as a practice at times not unlike other kinds of practices (like dancing or hockey) and that it can even be for amateurs. Turning away from traditional or more conservative ways of thinking about translation of poetry, and opening the topic to a wider world of possibility, among other things she spoke of “translation oceanic as desire.” But translation can also be a metaphor or way of seeing or thinking differently, of “reconsidering the inherited” or of forging new paths such as in the examples: “defund the police translation … divesting from racist brutality and investing in social services translation.” In the conversation that followed, the speakers also touched on the value of relationships and friendship, collaboration and improvisation in relation to translation. So much of this informs my reading of Some Girls in its openness, in the resonances and repetition of stories and feelings that occur in unexpected ways through and across the book. And it brings to life these ideas about the dynamic and wide-ranging nature of translation and storytelling, and the many perspectives we might bring to the practice and processes of those.

When reading through the Table of Contents, the book at first feels silly and playful, the titles capturing the fun and imaginative stories that kids might tell or act out with their friends. The book begins with “Girls Rolling Themselves,” which includes “ten new girls” about whom, “something” may be “uncanny.”

… Something believing and barely

visible. I din, in vain. Breath, too full. Persist, hinder, say too much,

as if it were Vegas.

Some get the stars shaken off of them. Some are given rose-scent. Some are fed

animal protein to fatten them up for the flood.

When they emerge, they are ten new girls, A thorough J.

This first piece sets up a lot of what is to come, though we may not realize it until later returning to this beginning. Often, in our world, it takes the unique or unexpected, the unusual or uncanny to call attention and create change, or to even notice something questionable in the first place. So while child’s play can be innocent and imaginative, it can also inform who we are as individuals and as members of communities as we grow into the world.

Some Girls is a book about the worlds of women, who are both insiders and outsiders in those worlds, some of whom exist in their own literal and figurative countries seemingly as outsiders “walk[ing] into the country they are from.” Some are unseen and kept silent. Some are forced to give up their stars, some are treated to perfumes and nice things, some are prepared for the challenges to come. In a way, the girls throughout this book are the myriad women of the contemporary #MeToo movement, women who have always existed and fought back, many of whom have never really been heard. The narrative play and the collaborative spirit in Some Girls’ construction and story-telling work to articulate a complex of nuances and examples. It includes stories of girls who are silenced and sidelined, of girls who compete with each other or work in solidarity and cooperation. It’s a call to other female-identifying people to recognize what’s been done to us and what we’ve also at times done to each other.

But action and imagination aren’t easy tasks in a society that polices women and girls, like in the piece “Is It Safe For Girls To Have Favorite Bears,” where we read, “Girl B on one small ride of light, I know it like the back of my wrist. The woke sunset is a painting. When I look too closely, I am flicked and whistled away by a distant cousin of civility.” Civility often being a stand-in for so many things, especially in regard to race and gender, of learning to critique or of speaking out.

And surely we all recognize the challenges of women continually trying to be recognized in the world of sports. In “A Line Of Five Girls With Golfballs In Their Mouths,” another five girls also have “tennisballs in their mouths,” and another five have “basketballs under their shirts.” And then:

With their left thumbs still hooked in the pockets of their cowboy jeans, each girl

uses their right hand to pull out a baggie of invisibility powder, rhythmically

shaking it all over themselves until there is nothing left to see excerpt for

beautifully fine residual vectors, the fine-tuned lines that they are.

Pared down to beautiful fine-tuned lines, at different points, the girls find themselves in the “middle of the US Open” and then the “US Open in tennis,” and when they get to “Madison Square Garden, they start dropping babies all over that basketball court as if the world was on fire and they needed to drop some weight so they could mad dash their way out of there. / Basketballs, I mean.”

Reading this piece, who doesn’t think about Serena Williams or other dominant women athletes? But we also think about the work of so many less famous or unknown athletes who have stood together, and who were or are vectors in direction and magnitude, intersecting and in relation, pointing toward a different future as if the world was on fire.

Or, in “Girl Soup” in which the first-person narrator, when asked where she wants to eat, responds that she doesn’t care (since she is “tired of being the one to make all the decisions”) and finds herself facing “a bowl of Girl Soup.” It’s a complicated situation, the cultural messaging that encourages women to compete and take each other down instead of working together and keeping others from being eaten alive. Fortunately, the narrator comes to recognize this, jumps into the soup to join the others, and “quickly round[s] up all the girls in the bowl into a large huddle.” The narrator then explains, “we have now obliterated two major problems: huddled together we are too large to eat, and also we’ve taken care of the problem of the eater.” It seems like a version of “if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem,” or something like that.

These are only a few examples from just the first 20 pages of the book. There are many more stories of girls in poetic play, causing “trouble” and agitating change. There are also visually beautiful poems--to an English speaker especially who may not know any Japanese--entirely in Japanese or that combine Japanese characters and English words. Some of the pieces include simple hiragana characters, which might evoke the idea of children’s books or more generally emphasize sound, for example in “Star Clusters like the Clatter”:

Because I don’t speak or read Japanese, I asked Sawako how a speaker of Japanese might read, hear, or see this poem. And while I was drawn to the visual, and intuited things like sound and repetition, her description is especially lovely:

I suppose for the Japanese speaker/reader, it might depend on their relationship to English, but ... to imagine it from the Japanese-only perspective: you can tell that it is grammatically (syntactically) woven into the syntax of the English line. The words are mostly onomatopoeia, the sound of "clatter" with a tiny bit of commentary, evolving towards the silence that ends the poem.

On the other hand, onomatopoeia is conventionally written in katakana, rather than the hiragana as it is here - so there is a softening effect, which could have been me thinking visually, melding the shapes of the Japanese to the shapes of the roman letters.

One of the few pieces written with line breaks and extra spacing, and more abstractly poetic than narrative, is “Girls Respond Quickly To A Call From Up High.” It’s also packed with concrete detail and resonates thematically with other ideas throughout the book. It begins, for example:

A long silk skirt billows out in all directions--

this wind rose, a garden of cardinal points

singing against convention--

Lyrically and in practice against convention, the girls are individuals who work together. In the middle of the piece:

the girl up above is on fire dancing or drowning

the girls in sum rising into and upward while burning

perfume ...

And ends:

there’s a girl on fire her soul intact

this is the way

things are going to be.

Another later version of “Girls Respond Quickly To A Call From Up High” is longer and written narratively in short prose block paragraphs. In a way, this piece fills in some details of the story, but also it gives us another way to see that story. It begins with “girls minding their business--taking photos, making soup, nursing babies--when the call comes.” They head to where the girl with the “billowing” skirt is, her head on fire, and “from a distance it is uncertain whether she is dancing or drowning.” Nonetheless, the girls “get to work.” They use their own hair, they bring relatives, they “sew the fabric of their own clothing” into that of the girl’s skirt and “gradually, all the colors and textures and luxuries of their own clothes dissolve into the silken fabric of the girl’s skirt, forging a ballast of fabric density.” One of the girls, who uses the pronoun “they,” sees everyone “throwing themselves wholly into this enormous skirt-tent operation” and “launches themself upward … all the way up until they are eye-to-eye with the enormous girl with her hair on fire.” And although “the struggle continues” there seems to be some hope for progress. Little by little, as the girls work together weaving a foundation to give the enormous girl stability, they also become stronger, unique individuals sharing their various colors and textures, eye to eye and set toward a more collective present and future.

Notes

Sawako Nakayasu, Poetry Foundation

“Star Clusters Like the Clatter” image from Some Girls Walk Into the Country They Are From (Wave, 2020). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

The early version of “Girls Respond Quickly To A Call From Up High” was written by Karen An-Hwei Lee. It's based on the version by Sawako Nakayasu that appears later. Both are discussed above.