Before jumping into this conversation with poet Danielle Badra, it is important to note that she is indeed my wife. I want to mention this upfront for transparency and also as this fact means that you will be getting insider information into this author’s process and experiences around publishing her debut poetry collection Like We Still Speak.

We also want to acknowledge that this interview was formed before we learned of Etel Adnan’s recent passing. It feels significant to think of the way this poetry prize, through the University of Arkansas Press, curated by Fady Joudah and Hayan Charara, was designed to honor Etel Adnan’s legacy as a world-renowned poet, novelist, essayist, and artist, giving space to celebrating and fostering the writings and writers that make up the vibrant and diverse Arab American community. Adnan’s legacy lives on, and her work will continue to inspire and illuminate.

* * *

Holly Mason Badra: Congratulations on winning the 2021 Etel Adnan Poetry Prize! In any way you’d like, can you describe what that means to you to win this prize specifically?

Danielle Badra: First of all, it’s an honor to be awarded a prize named after Etel Adnan, an incomparable titan of the poetry and art world, whose work I studied during my MFA program. I would’ve never imagined my debut poetry collection would be published through a prize named after Adnan. Also, to be awarded a prize that is for writers of Arab heritage is a deeply heartfelt honor for me. When I found out I won the prize, I was in the midst of caring for my dying father. My father is who I get my Arab heritage from and there was a deep sense of both relief and gratitude in that moment. Relief that I’d have the opportunity to tell him this amazing news before he passed. Gratitude that his heritage is what allowed me to receive this incredible prize. It made it feel like my father was intrinsically a part of this publication.

HMB: I remember the day we visited your father, Baba, where he was receiving hospice care. I remember you holding his hand while he was in bed and reading off the news to him of winning this prize. Do you remember how he responded?

DB: Ah yes that was a beautiful experience, one that I’ll always cherish. My baba’s initial words after I read the publication announcement to him were, “I’m ready to cry. I’m all choked up.” He was battling dementia at this point and was unable to read the announcement himself, and I was not entirely sure he would be able to process the information I read to him either. But, it is clear that he understood the immensity of that moment. He said the news made him feel wonderful and that he was extremely proud of me. I cannot describe adequately how thankful I am to have had that moment with him. He died about a month later and he never got the opportunity to read this book but he is in this book. He is absolutely part of Like We Still Speak, and I like to think he knows it.

HMB: Approximately how long did it take you from start to finish to write the poems and put together Like We Still Speak? And what within that time kept you writing?

DB: From start to finish I’d say this book took approximately my whole lifetime to write if we are speaking in terms of lived experiences that inform the book. If we are speaking in terms of when I started writing the poems and when the concept for the book came to me, I’d say it took roughly five years. The majority of the poems were written in the first few years after conceptualizing the collection and then I spent a couple of years submitting and revising. There are a few poems that I wrote immediately after my dad died, so those are the newest poems clearly written after the manuscript was accepted for publication, for example, “Baba’s Fragments.” But there are also some poems in the book from 2012 and 2013 when I was obsessively writing contrapuntal poems in conversation with my deceased sister, Rachal. These poems ended up making it into my chapbook, Dialogue with the Dead, and I pulled a few from that collection to include in Like We Still Speak, for example, “An Entire Universe.”

HMB: What was the process like for choosing the book’s cover art? And what are your own meditations on that image?

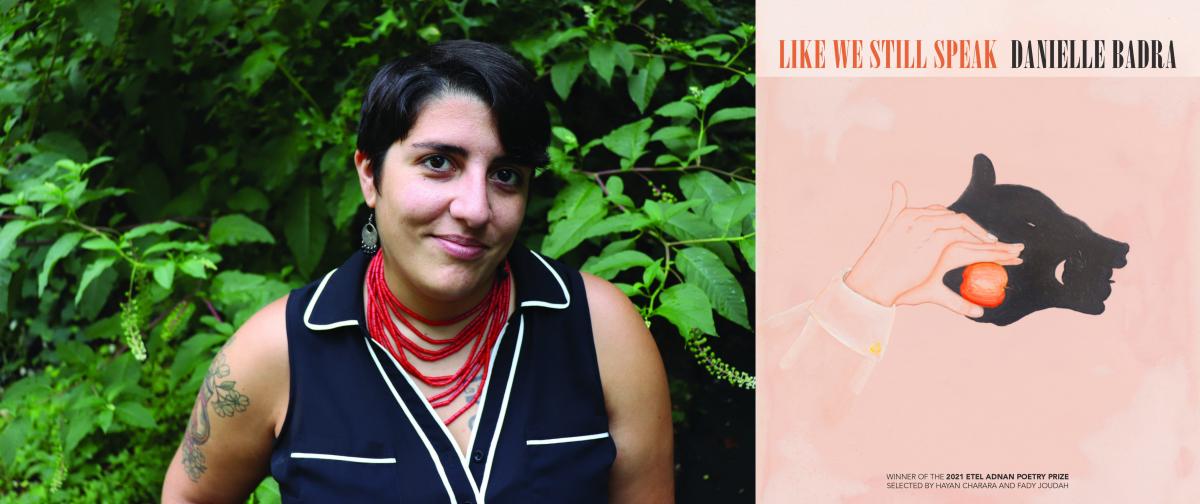

DB: The cover art process was very fun but also very vulnerable. Here was a fellow artist responding to my work by presenting images that seem to reflect or connect to Like We Still Speak. It’s funny because my whole collection is essentially one form or another of call and response so you’d think I’d be comfortable with the process. But, for some reason, I felt extremely vulnerable during that process. I said no to a lot of initial images that were presented because they were grey, dark, more interested in death than I felt they needed to be. Yes, death is an intimate part of this book, but it is more about remembrance and keeping my dead alive through this work. Working with Anthony Blake through University of Arkansas Press was an incredible experience as they really took the time to listen to my input and had the patience to keep looking until we found the perfect image. The pink cover art by Raúl Ortega Ayala with the shadow puppet of an animal with an apple in its mouth speaks to the idea of storytelling. It speaks to the polyphonic mode of this book in that you have the story of the animal with the apple but you also see the hands making the story happen. This also speaks directly to one small image in “Ode to Onion” when my sister and I are making shadow puppets in a closet at our grandmother’s house. It’s another delicate glimpse into our sisterhood. As a side note, however, our shadow puppets never ended up looking nearly as cool as this cover art. Mostly sharks and alligators.

HMB: It seems to me that you use form and the act of being in conversation with others (whether writers, artists, creators, family, or the beloved) as a way to speak alongside others in various capacities. How do you approach this responding and interactive process when writing these poems?

DB: I like to think of this collection as a gallery space that contains the voices of my community. That was the approach I took in writing this book that I wanted to include my family, my friends, poets and artists I admired, my love. I initially put out a call for submissions, and I received so many amazing entries from my loved ones. I then spent a couple years going through those submissions and attempting to respond to everyone. Unfortunately, not every voice from that call for submissions made it into this collection but that’s really a matter of me not finding a way into every submission and not a reflection at all on the quality of what I received. When it comes to the call and response process for me, I take several different approaches. One of my favorite approaches is the contrapuntal form where I take a portion of written text and highlight that in one column on a page and then I go line by line and respond to the text, creating two separate poems in the two columns but also a third poem that exists between the columns. I also engaged in a bit of ekphrasis for some of these poems, in particular, “Child of the Universe.” That poem was in response to an incredible piece of artwork titled “Child of the Universe” by friend and local artist, Mojdeh Rezaeipour. The most important part of responding to any text or artwork for me is to spend time with it, study it, connect to it, and then find a way to respond. There needs to be a connection before there is a response or else the response will feel forced.

HMB: Is there a poem (or two) in the collection that feel(s) particularly special to you? And can you expand on why?

DB: Yes. Absolutely. “How to Read to Your Father in His Hospital Bed during a Global Pandemic” is one of the poems in this book that means a great deal to me. My father was a Roman Catholic priest in his younger years. He left the priesthood before having my sister and I, but he never fully left the Catholic church. For nearly forty years my father was asked by our church to lead Good Friday mass. He wrote his own “Stations of the Cross” specifically for that Good Friday mass, and he edited it year after year but the core of it always stayed the same. At the height of the pandemic, I was unable to be with my father as he was isolated in a hospital bed separated from everyone he loved. We called each other regularly so he could have some form of human interaction outside of his doctors and nurses. By Good Friday, my father had been in the hospital for nearly an entire month and his health was only deteriorating further each day. I knew that this would likely be his last Good Friday and so I surprised him with a reading of his “Stations of the Cross.” We went through the entire fourteen station reading and between each station he recited, “We touch the wood of your cross and we remember.” I’m not a religious person anymore but that moment was a religious one for me. I needed to memorialize that moment and so that’s where this poem comes from.

Another poem that means a great deal to me is the “Sister Sister” opening poem. My sister, Rachal, wrote the right side of this poem as a gift for me for my 23rd birthday. At the time I thought, “You just didn’t want to spend money on a gift so you wrote me a poem.” And I scoffed at it because I was the little sister and I was prone to being highly judgmental of Rachal’s gift selections which were almost always handmade. Any ways, after her death, this poem gift took on so much greater meaning to me. The fact that she describes us coming to a point in our lives where we hardly know each other anymore and where we would speak a different language. Something about it felt prophetic. Many of her poems felt prophetic when I read them after she died. It took many attempts to respond to this poem because it held so much weight for me. But I really love where this poem landed and that it is the opening poem for this collection.

Finally, I love “Love Poem.” Mostly because it is in conversation with you, Holly Mason, my wife, my love. But also because I love that it is not a cheesy love poem. It is dynamic and explores navigating grief while growing a relationship, grief on both sides of the poem. I love that it is the final poem of the collection and that I start and end the collection with two people that I love, my sister at the beginning and my wife at the end. It feels very right there. And finally, I love that sometimes during a poetry reading I can ask Holly to join me in reading that poem side by side.

HMB: I see a theme of the sister figure as a space of sanctuary and safety (“shelter from the storm”) in many poems. These moments feel heartbreaking and also unequivocally beautiful. As the note in the back of the book articulates, many of the poems in the book are in conversation and speaking alongside your sister’s poetry that you found once she passed. Like We Still Speak keeps your sister’s voice and art alive. Do you happen to know of any of Rachal’s favorite poets, writers, books or scholars?

DB: Rachal was an avid reader. She was extremely intelligent and quite the intellectual. She loved reading history and poetry and she studied Latin; as a result, one of her absolute favorite books was Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy, specifically, The Inferno. She even had opening lines from the book tattooed on her back: “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita / mi retrovai per una selva oscura” which roughly translates to “Midway upon the journey of life I found myself in a forest dark.” This tattoo as well as several of her poems, as I’ve said previously, seem prophetic to me even nearly a decade after her death. I say this because she often wrote that she may die young. Much of her writing dealt with the concept of her own death and even questioned whether she had experienced death before. We found out once she passed that her “fainting spells” she’d experienced since high school were actually instances of her heart stopping and starting again, little deaths. She definitely knew there was a thin veil between this life and what comes after, and she was very interested in exploring both spaces. It felt both haunting and comforting to read her poetry about death. For example, her final poem, which you can read in the frame of “The Phillips Collection” poem, she wrote this final poem on the last day she was alive, February 14, 2012, while she worked at The Phillips Collection. She wrote about a gray painting and about how all the color would be drained from the world and how parents would kiss their children goodnight and carry this grayness with them. I read this poem in her black moleskine book while sitting in the hospital ER holding her purse at 7am the morning of February 15, 2012. I remember thinking to myself, “what the fuck?” but also “she must’ve known this storm was coming.”

Rachal also loved reading Sylvia Plath, Sharon Olds, Anne Sexton.

HMB: If you could spend one day with Rachal, what would you want to do in those 24 hours together.

DB: If I could spend one more day with Rachal, I would spend the day at the beach with her. The beaches of Lake Michigan were her absolute favorite. Whatever beach she wanted to be at, I would be there with her. Our toes in the sand. The occasional cool down dip in the water. We’d likely build a sandcastle at some point or a sand graveyard. She would read a book. I would bug her to stop reading and go in the water with me for longer than just a dip. Maybe we would take a break for ice cream. We would tan together and compare the length of our arm hair. I would give her as many hugs as possible and make her laugh constantly. I would give anything to watch her laugh at one of my stupid jokes again. Maybe I would ask her some unanswered questions about her life that I’ve wanted to ask since she passed. But, maybe those questions were meant to go unanswered so instead I’d just let us catch up instead. I’d want the day to end by recording video clips of her saying “I love you” to me, singing a Fiona Apple song, and playing the family piano at our dad’s house so that I could play it on a loop any time I miss her.

HMB: What do you think your dad would say about your book—imaging it in his hands, and he has finished the last poem—what do you imagine he’d say to you?

DB: I imagine my father would look at me with tears in his eyes and say, “Dani Baby, I’m all choked up.” Then he would probably proceed to open up his most recent memoir or poetry manuscript and he would read that to me out loud for a couple hours while we drink whiskey gingers.

Danielle Badra is a queer Arab-American poet. She was raised in Michigan and currently resides in Virginia. Her debut poetry collection, Like We Still Speak, was selected by Fady Joudah and Hayan Charara as the winner of the 2021 Etel Adnan Poetry Prize and is published through the University of Arkansas Press. Her poems have appeared in Guesthouse, Cincinnati Review, Mizna, Beltway Poetry Quarterly, Split This Rock, Duende, and elsewhere.

Holly Mason Badra received her MFA in Poetry from George Mason University. Her poetry, essays, reviews, and interviews appear in The Adroit Journal, Rabbit Catastrophe Review, The Northern Virginia Review, Foothill Poetry Journal, 1508, The Rumpus, CALYX, So to Speak, and elsewhere. She has been a panelist for OutWrite, RAWIFest, and DC's Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here events as a Kurdish-American poet. Holly is currently on the staff of Poetry Daily and lives in Northern Virginia with her wife and dog.