In graduate school Laura Kasischke assigned our workshop an impossible task: for each student to bring in an example of the perfect poem. I’ll admit I dodged the responsibility when it was my day for show-and-tell. I could have presented June Jordan’s “In the Times of My Heart,” a tiny, perfect poem:

In the times of my heart

the children tell the clock

a hallelujah

listen people

listen

I would have talked about how this poem expresses the unfettered joy of small moments and how, read in relation to Jordan’s oeuvre, it is a celebration of queer, Black womanhood as a form of resistance. This perfect poem uses celebration as a form of resistance. I could have passed around William Carlos Williams’s “This is Just to Say” and Kenneth Koch’s “Variations on a Theme by William Carlos Williams” and talked about how the perfect poem is one that speaks across generations: a conversation across time (the times of our hearts) and I would have insisted that as much as the assertion that writing is a lonely office holds true, it’s also a vocation deeply rooted in friendship and community. Instead of moving from the conceptual idea of perfection into some imperfect iteration of my own half-known predilections, though, when it was my day to share, I asked the workshop participants to line up, and I hugged each person in turn.

I compared the perfect poem to a hug for several reasons. First, I believe the poem is a container for a complex set of emotions that are difficult to put into words. Second, the same gesture or utterance can carry opposite or even contradictory valances and can convey different information every time we return to it. A hug is a repetition with many differences. So, too, with a poem. Of course this comparison risks veering toward sentimentality, and that’s another reason for making it. There must be something at stake in a perfect poem, some risk or vulnerability. A hug in an academic classroom argues that we—as teachers, as students—must show up to learning with our full and complicated selves; the action risks the claim that the personal is pedagogical. In a more general sense, a hug risks the same thing that any communication does—being misunderstood—a risk whose amplification is directly proportional to the extent to which we show up with our unique and full selves. This is precisely the risk with translation. The perfect poem points toward that human experience which everyday language can’t quite reach. Its translation-cousin is the untranslatable, which doesn’t mean there’s no way to translate a word or phrase, but that it’ll take up more time, or take up more space on the page. To say it another way: the more the uniqueness of one culture shows up in a word, the more likely it is to be misunderstood in translation.

If you scan through online lists of untranslatable words, you’ll see the Dutch word “gezellig.” The Dutch dictionary, from what I can tell, explains the adjective and adverb forms as something like both “cozy” and “sociable.” Folks have compared it to the Danish word “hygge” and similarly suggest that it encapsulates the heart of the culture. If it’s that simple, though, why is it untranslatable? I set off on a mission to understand.

Diane Daniel / Sculptures made from recycled materials in the design space

I met Diane Daniel at a design hub in Eindhoven, a town in the southeast of the Netherlands. Eindhoven is the birthplace of the technology company Philips and housed its world headquarters until 1997, with the exception of World War II, when the company moved to New York and the town was scarred by bombings. Today much of the industrial infrastructure of the multinational company is being repurposed. This design hub—a combination gallery, storefront, studio space, and restaurant—has taken over a large warehouse complex. We toured the shop with its reclaimed wood furniture, reglazed porcelain ware, and quilted rugs, and I talked with Diane about the extent to which gezellig maps onto U.S. culture. Diane is an expat from the East Coast and a freelance writer who’s been living in the Netherlands for over two years, but with a Dutch partner, she has extensive experience with Dutch culture. She said the word’s a mix between “hospitable, cozy, and fun” and that definitely a backyard barbecue or a house reading could qualify as gezellig. A large, industrial space like the one we were in might also make the cut, Diane said, because it’s been so artfully curated with design pieces that are “more warm than harsh.” I hadn’t imagined a warehouse as cozy, but perhaps this is the cultural mismatch: for those who are accustomed to the Craigslist-apartment-listing meaning of “cozy,” some uses of gezellig might come as a surprise. As this building’s wall-to-wall windows, concrete floors, high ceilings and €18,000 kitchen islands attest, gezellig is not always synonymous with “tiny,” “cramped,” and “within a poet’s budget.”

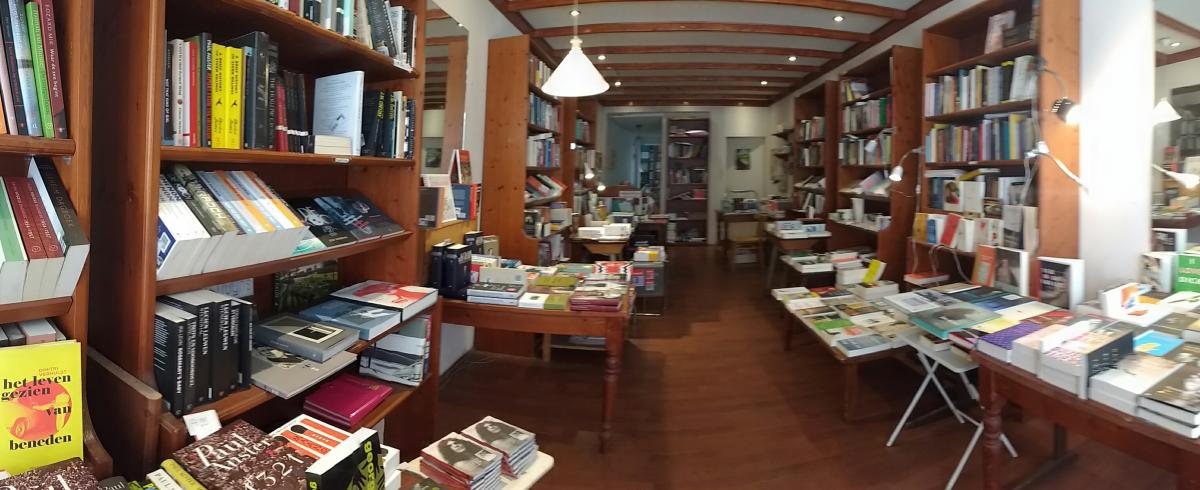

Inside Boekhandel Spijkerman

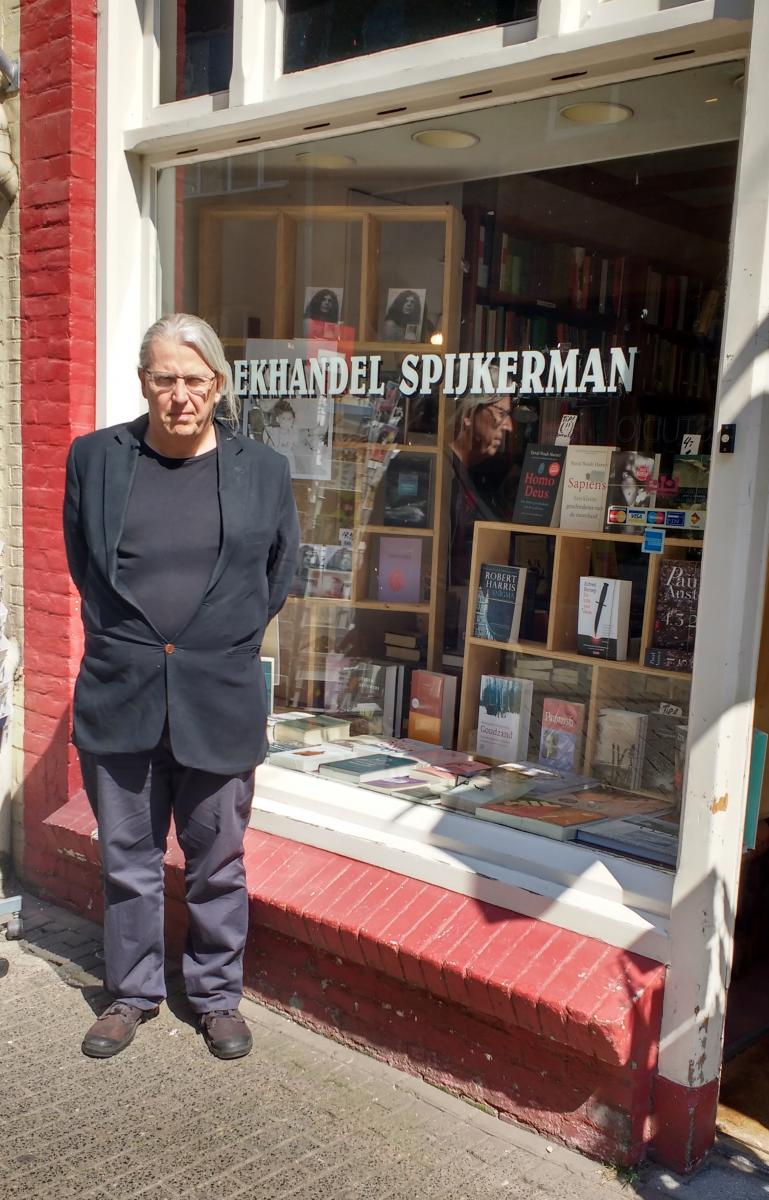

Boekhandel Spijkerman, a small, locally-owned bookstore in Eindhoven, better matches my expectations of gezelligheid. The untreated pine shelves in the front window give way to a long, narrow, white walled room. Chestnut colored bookshelves and a patchwork of low tables line the walls and create a narrow aisle down the middle of the shop. The crown molding is a simple framing of slim, dark wood with repeating crossways beams that run the room’s width like a train track. Dutch posters in the window advertise lectures on Joyce and Spinoza. When I asked the owner, Stein Spijkerman, if the word gezellig reflects the speaker’s internal mood or the atmosphere of the room, he clarified that gezellig is highly subjective and interior. Not only might two people disagree about the level of gezellig in a given place, but there are also different kinds of gezellig. His bookstore and a place like Barnes and Noble might both have a gezellig-factor, for example, but they evoke very different feelings. I can see what he means: his poetry selection looks to be a carefully curated set of small press volumes in Dutch whereas the larger, more commercial bookstore in the city center has a wide, popular selection of both Dutch and English language poetry. Referring to the more commercial bookstore Mr. Spijkerman explained, “they have coffee and they have music. They have nice colors.” He touched the nose of his own glasses. “They have glasses.” You’ll find a place more or less gezellig depending on what you’re looking for. He added that while mostly the word is positive, “gezellig is also a bit bourgeois,” a way to keep things superficially pleasant, like when, on your way to dinner, your friend says, “We’re going out for dinner. It’s going to be gezellig. We don’t talk about Trump; we don’t talk about the environment. We keep it gezellig.” One man’s pleasant can be another man’s pleasantries.

Stein Spijkerman

In this column, gezellig is not superficial. This term, with its gradations of cozy conviviality that defy direct translation, feels like a near-perfect container for a column about poetry communities. I’ll be bringing you reports from literary gatherings in Europe: festivals, independent bookshops and reading series, and innovations on and off the page. My hope is to relate some of what makes each of these groups unique, and to relay the qualities of gezelligheid poetry and poetics found there. This column is a place for something like cozy, social poetry. Should I risk it? Something like a hug.

Laura Wetherington’s first book, A Map Predetermined and Chance (Fence Books), was selected by C.S. Giscombe for the National Poetry Series. She teaches in Sierra Nevada College’s low-residency MFA Program and co-edits textsound.org with Hannah Ensor. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.